Phyllomedusa Trinitatis

From Handwiki

From Handwiki

| Phyllomedusa trinitatis | |

|---|---|

| |

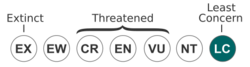

Conservation status

| |

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Hylidae |

| Genus: | Phyllomedusa |

| Species: | P. trinitatis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Phyllomedusa trinitatis Mertens, 1926

| |

Phyllomedusa trinitatis is a species of frog in the subfamily Phyllomedusinae. It is found in Trinidad and Tobago and Venezuela. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forests, subtropical or tropical moist montane forests, moist savanna, subtropical or tropical moist shrublands, freshwater marshes, heavily degraded former forests, ponds, and canals and ditches. It is threatened by habitat loss. An interesting characteristic of this frog is it has no webbing on the hands and feet. Researchers suggest that the unique toes might be due to both habitats and its predation behavior. A common predator of this frog's tadpole is dragon fly larva. It can produce poisonous secretion for predator defense.

Description

P. trinitatis is also known as the Trinidadian monkey frog, the leaf-nesting frog, and the Trinidadian leaf frog.[2] P. trinitatis has parotid glands near its eyes.[3] The frog has black and yellow eyes while much of the rest of the body is a bright green. The frog's chest and chin are brown.[4] However, the color of the frog can also differ depending on its local environment and ability to achieve homeostasis in different temperatures.[2] The frog is described to have no webbing on the hands and feet.[5] Additionally, it has smooth skin on the back dotted with small tubercles throughout. Males are described to lack vocal slits.[5]

Distribution

The frog can be found throughout northern Venezuela specifically in the following states Distrito Federal, Sucre, Vargas, Miranda, Aragua, Carabobo, Yaracuy, Monagas, north of Bolivar and Guárico, and eastern Falcón.[6]

Diet

Based on such studies, the researchers proposed that P. trinitatis is often stalking its prey due to its above average size and relatively slow movement.[7] They suggest that the toe pad shape of P. trinitatis might be related to its predatory behavior and not just its habitat.[7] P. trinitatis is also known to eat insects such as field crickets.[2]

Predators

In a study conducted in Trinidad, West Indies, researchers studied predation of Phyllomedusa trinitatis tadpoles by the dragonfly larvae Pantal flavescens, one of the predators of P. trinitatis during its tadpole stage.[7] Researchers studied whether the larvae had a preference towards tadpoles of P. trinitatis or Physalaemus pusulosus as prey, especially as density of each species varied. Their results demonstrated that the relative prey density has no significant bearing on the dragonfly's preference of hunting for P. trinitatis tadpoles over Physalaemus pusulosus[7]

Prior to adulthood, phorid flies in Trinidad are also known to decimate clutches of P. trinitatis eggs as a predator.[8]

Defense

This frog exhibits a host of defenses to evade predators and survive in hostile environments. As the frog flees from predators, it is capable of releasing poison from glands found on its back.[9] Males may also remain silent rather than calling to prevent attracting predators to their locations.[9]

Furthermore, probing the glands of P. trinitatis via electrical stimulation, scientists have isolated insulinotropic peptides from the frog's secretions. After purifying the secreted fluids of a few frogs, scientists purified four peptides that significantly promoted insulin release in BRIN-BD11 cells, cells capable of secreting insulin.[4] Researchers were able to isolate a 28-amino acid peptide fully homologous to the C-terminal of the precursor to dermaseptin BIV.[4] These results suggest that P. trinitatis secretes an antimicrobial as part of its immune defense, though the specific mechanism of action is still unknown.[4]

Other studies have identified other defense peptides secreted from the frog's skin. One study found 15 dermaseptin peptides with varying antimicrobial properties and evolutionarily conserved amino acid regions.[10] One notable peptide discovered had only one cysteine residue in its structure (LTWKIPTRFCGVT), which is an uncommon distribution.[11] The strongest antimicrobial peptides found were phylloseptin-1.1TR and 3.1TR. Like defense proteins found in other frogs, both of these peptides exhibited more potency against Gram positive compared to Gram negative bacteria.[11]

There are also studies that provide insight into the structure-activity relationship between phyllo statins. Such studies related to immunomodulation and insulinotropic activity may represent that these frogs can be used for development of drug templates for anti-inflammatory and type 2 diabetes treatment.[12]

Mating

The mating season for P. trinitatis is usually around the end of the dry season until the beginning of the rainy season.[9] The species exhibits sexual dimorphism, the female is reported to be more massive than the male.[9] In other Phyllomedusa, a silent male will hijack a mating pair as an alternative mating strategy, but this behavior has not been reported in this frog.[9]

The frogs mate in foliage neighboring small bodies of water, including ditches.[8] P. trinitatis is known to call out to mates much like other frogs do. In an audio spectrogram of the call of the P. trinitatis, it was evidently a principal note along with five secondary notes.[13] The loud call can function as a deterrent for other males attempting to seek female partners.[13] The fundamental frequency was believed to be 500 Hertz while the dominant frequencies were considered to be around 800 Hertz[5].. Additionally, males that tend to be more vocal, tend to travel greater distances in the environment. However, some males have been reported to stay in place while calling out to other frogs.[14] In the context of silent communication, it is relevant to also consider that the frogs, specifically the males, conduct a leg-waving behavior to demonstrate their strength to foes.[9] This can be done to avoid physical fighting.[9]

Breeding site attendance

Most female only attend once in breeding, but for those who attended more than once, the nesting interval averaged 27.6 days. Males showed high pond loyalty; a few participate in two ponds while always preferring one over the other. There are three attendance patterns for men. Stays for multiple nights, sporadic attendance, and only once. Most frogs appearing on multiple nights. However, there is also no evidence that a particular model is the best choice for reproductive success.[15]

Development and life cycle

Physical development

The first paper to explain the development of toe pads in Phyllomedusa trinitatis used light and scanning electron microscopy to show that the adult toe pad has some mucosal pores in a sea of "hexagonal shaped cells".[8] The study also found that the frog has pads that are flat and lack “lateral grooves” on the front of each individual digit. This distinguishes the Trinidad frog from other tree frogs or hylids that have differing features, such as convex pads.[8] Additionally, P. trinitatis is described to have about 12 cell layers—including columnar and cuboidal cells—on its toe pad.[8]

Using Gosner's (1960) staging table for frog development, they showed the stage by stage changes that take place in frog toe pads. For the purposes of this page, when a stage is mentioned it will be in reference to Gosner's staging paradigm rather than Kenny's staging (1968) for example. They noted that in earlier stages of development, the forelimb appears to develop at a faster rate than the hindlimb based on how separated the digits were. By stage 38, all digits were layered with an epithelium of simple squamous cells.[8] At stage 39, the long toe had a notably expanded distal end and the toe pad had widened.[16] At stage 40, the circumferal groove became very apparent in the toe pads and was fully developed by stage 46, the end of metamorphosis.[8]

Notably, researchers have claimed that unlike other species of frogs, P. trinitatis has no evidence of having hatching gland cells during its development. Looking at Gosner stages 18 to 23, the scientists did not see hatching gland cells on the heads of the frogs.[17] These findings suggest that P. trinitatis might have a different hatching mechanism distinct from other frogs of other species.[17] Other studies, however, have shown conflicting results.[8] Embryos farther along in their development were shown to have hatching gland cells on the laterodorsal surface of the head.[8]

Life cycle

Concerning the nesting behaviors of P. trinitatis, it appears to exhibit similar behavior to other Phyllomedusa frogs. Once an egg clutch is produced, it can sometimes be found as high as trees or as low as grass when better leaves for nesting cannot be found.[8] It is known that P. trinitatis hatches on leaves that are nearby water. As a result, the tadpoles fall into the water once fully mature.[7] Usually, when the egg clutch is released, it is surrounded by a leaf to separate it from the environment and offer protection. This configuration may sometimes shield the clutch from rainfall. This makes sense considering that incubation in water kills Phyllomedusa eggs, a unique phenomenon for an amphibian species.[8] The mechanism by which such embryos paradoxically survive with potential issues of hypoxia are yet to be discovered.[18]

The eggs are later covered with jelly capsules or plugs produced by the mother.[8] The jelly plugs have been reported to be made of 96 to 97% water and 2 to 3% dry matter.[8] The jelly capsules possess a dense core surrounded by a matrix. It has been shown that the capsules are positive for alcian blue while the matrix is positive for periodic acid-Schiffs, indicating a composition of different mucopolysaccharides. It also appears that the jelly plug and capsule prevent water absorption during rainfall.[8]

Researchers reported that P. trinitatis has no evidence of leaf preference when deciding on where to have their nest.[8] The same can be said for the number of leaves they used. After observing 17 nests, they found that 35% of the frogs used 2 leaves, 41% used 3, 12% used 4, and 12% used more than 4. Hatching success has also been tested on dead or healthy leaves and no significant difference was observed between control and experimental groups.[8] Of note, as one embryo hatches, experiments suggest that the embryo influences other eggs to somehow also hatch.[8]

Research limitations

One study focused on best practices for tracking the frogs for field research and found that neither bobbins or radio tags were perfectly suited for the frog. Initial attempts of using fluorescent dye proved ineffective as the dye had a deleterious impact on the frog.[19] Bobbins and radio tags had no significant effect on the distance the frog traveled, even though the tracking devices were typically 15 to 20% of the frog's weight.[19] However, frogs became lethargic and less mobile by the third day of the trial. The radio tag failed to locate the frogs in areas of high altitude or vegetation as the signal became less clear. On the other hand, placing bobbins on the frogs often led to physical harm like bruising.[19]

References

- ↑ IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2020). "Phyllomedusa trinitatis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T55867A109536663. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T55867A109536663.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/55867/109536663. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kirton, Sparcle. "Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Leaf-nesting Frog)". UWI. https://sta.uwi.edu/fst/lifesciences/sites/default/files/lifesciences/documents/ogatt/Phyllomedusa_trinitatis - Leaf-nesting Frog.pdf.

- ↑ Walls, Jerry G. (1996). Red-eyes and other leaf-frogs. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H. Publications. ISBN 0793820510.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Marenah, L.; McClean, S.; Flatt, P. R.; Orr, D. F.; Shaw, C.; Abdel-Wahab, Y. H. A. (August 2004). "Novel Insulin-Releasing Peptides in the Skin of Phyllomedusa trinitatis Frog Include 28 Amino Acid Peptide From Dermaseptin BIV Precursor". Pancreas 29 (2): 110–115. doi:10.1097/00006676-200408000-00005. PMID 15257102.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Barrio-Amorós, César L. (7 September 2006). "A new species of Phyllomedusa (Anura: Hylidae: Phyllomedusinae) from northwestern Venezuela". Zootaxa 1309 (1): 55. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1309.1.5.

- ↑ Barrio-Amorós, C.L. (30 December 2004). "Amphibians of Venezuela, Systematic list, Distribution and References; an Update". Revista Ecología Latino Americana 9: 1–48. https://www.academia.edu/es/4165425/BARRIO_AMORÓS_C_L_2004_Amphibians_of_Venezuela_Systematic_list_Distribution_and_References_an_Update_Revista_Ecología_Latino_Americana_9_3_1_48.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Sherratt, Thomas N.; Harvey, Ian F. (1989). "Predation by Larvae of Pantala flavescens (Odonata) on Tadpoles of Phyllomedusa trinitatis and Physalaemus pustulosus: The Influence of Absolute and Relative Density of Prey on Predator Choice". Oikos 56 (2): 170–176. doi:10.2307/3565332.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 Downie, J. Roger; Nokhbatolfoghahai, Mohsen; Bruce, Duncan; Smith, Joanna M.; Orthmann-Brask, Nina; MacDonald-Allan, Innes (18 June 2013). "Nest structure, incubation and hatching in the Trinidadian leaf-frog Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Anura: Hylidae)". Phyllomedusa: Journal of Herpetology 12 (1): 13–32. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v12i1p13-32.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Smith, Joanna. "Glasgow University Exploration Society Trinidad Expedition 2001". http://www.glasgowexsoc.org.uk/reports/trinidad2001.pdf.

- ↑ Mechkarska, Milena; Coquet, Laurent; Leprince, Jérôme; Auguste, Renoir J.; Jouenne, Thierry; Mangoni, Maria Luisa; Conlon, J. Michael (1 December 2018). "Peptidomic analysis of the host-defense peptides in skin secretions of the Trinidadian leaf frog Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Phyllomedusidae)". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D: Genomics and Proteomics 28: 72–79. doi:10.1016/j.cbd.2018.06.006. PMID 29980138. https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/en/publications/91358d56-8844-4b2b-8476-4f4b73af6343.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMechkarska-2018 - ↑ Pantic, Jelena; Guilhaudis, Laure; Musale, Vishal; Attoub, Samir; Lukic, Miodrag L.; Mechkarska, Milena; Conlon, J. Michael (April 2019). "Immunomodulatory, insulinotropic, and cytotoxic activities of phylloseptins and plasticin‐TR from the Trinidanian leaf frog Phyllomedusa trinitatis" (in en). Journal of Peptide Science 25 (4): e3153. doi:10.1002/psc.3153. ISSN 1075-2617. PMID 30734396. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/psc.3153.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rivero, J; Esteves, Andrés (1969). "Observations on the agonistic and breeding behavior of Leptodactylus pentadactylus and other amphibian species in Venezuela". Breviora 321: 1–14. https://archive.org/details/biostor-4219.

- ↑ Kirton, Sparcle. "Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Leaf-nesting Frog)". UWI. https://sta.uwi.edu/fst/lifesciences/sites/default/files/lifesciences/documents/ogatt/Phyllomedusa_trinitatis - Leaf-nesting Frog.pdf.

- ↑ Boyle, Cameron M.; Gourevitch, Eleanor H. Z.; Downie, J. Roger (2021-06-30). "Breeding site attendance and breeding success in Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Anura: Phyllomedusidae)" (in en). Phyllomedusa: Journal of Herpetology 20 (1): 53–66. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v20i1p53-66. ISSN 2316-9079. https://www.revistas.usp.br/phyllo/article/view/187588.

- ↑ Ba‐Omar, T. A.; Downie, J. R.; Barnes, W. J. P. (February 2000). "Development of adhesive toe‐pads in the tree‐frog ( Phyllomedusa trinitatis )". Journal of Zoology 250 (2): 267–282. doi:10.1017/S0952836900002120.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nokhbatolfoghahai, M.; Downie, J. R. (1 August 2007). "Amphibian hatching gland cells: Pattern and distribution in anurans". Tissue and Cell 39 (4): 225–240. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2007.04.003. PMID 17585978.

- ↑ Hutter, Damian; Kingdom, John; Jaeggi, Edgar (2010). "Causes and Mechanisms of Intrauterine Hypoxia and Its Impact on the Fetal Cardiovascular System: A Review". International Journal of Pediatrics 2010: 401323. doi:10.1155/2010/401323. ISSN 1687-9740. PMID 20981293.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Gourevitch, Eleanor H. Z.; Downie, J. Roger (18 December 2018). "Evaluation of tree frog tracking methods using Phyllomedusa trinitatis (Anura: Phyllomedusidae)". Phyllomedusa: Journal of Herpetology 17 (2): 233–246. doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v17i2p233-246.

Wikidata ☰ Q2699800 entry

|

Categories: [Phyllomedusa]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 05/09/2023 14:41:00 | 2 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Phyllomedusa_trinitatis | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF