Black Sox Scandal

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 7 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 7 min

The Black Sox Scandal occurred during the 1919 World Series between the Chicago White Sox of the American League and the Cincinnati Reds of the National League, in which eight baseball players of the Chicago team conspired with gamblers to intentionally "throw" (or lose) the Series. The fallout from the scandal caused the owners of individual teams to create a powerful commissioner of baseball in Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, whose first step at reforming baseball was to ban eight players for life without giving them due process. The star player "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, whose play was outstanding and even broke a record for the most number of hits, is widely considered to have been innocent but made into a high-profile scapegoat for the benefit of baseball owners.

The handling of his incident can be described as an injustice to Shoeless Joe Jackson which resulted from a denial of due process in the context of an administrative decision-making. If this had happened today, it seems likely that he would have been able to obtain reversal of the decision by challenging it in court.

Contents

Prelude[edit]

Charles Comiskey was a former big league player for various teams in baseball until he became the owner of the White Sox in the American League from 1900 to 1931. As the owner, he led the White Sox to five A.L. championships, and the World Series of 1919 promised to be the best year in baseball, as he boasted about having the best team on any field.

But Comiskey was a miser, and notorious for it. His players were among the lowest-paid in the league, and being subject to the "reserve clause" they could do nothing about it. He even forced his players to do their own laundry, as he wouldn't hire extra help to deal with the player's uniforms. The players responded for several weeks in 1919 by wearing their filthy uniforms on the field; the eventual buildup of the dirt, sweat, and grime turned their once-white uniforms to a dark shade of gray in places, resulting in the nickname of "Black Sox" being bestowed on them before the scandal took place (Comiskey had the uniforms removed from the lockers and the players fined for the infraction [1]).

Interest in baseball was low as a result of American involvement in World War I, but climbed considerably at war's end, so much so that baseball owners decided upon a best-of-nine format instead of the traditional seven games for the 1919 World Series. Interest in the betting on baseball also climbed as well; gamblers had for years hung around the parks betting on individual games while the occasional rumor circulated that a player was supplementing his income by throwing games. Comiskey, aware of the rumors, posted signs at his park banning gambling, but had failed to see the other signs pointing to the resentment against him and the tempting offers of high rewards from gamblers. [2]

The Fix[edit]

The majority of accounts and sources indicate that the fix was started by first baseman Chick Gandil wanting to get even with Comiskey; he allegedly talked to pitcher Ed Cicotte about throwing the World Series. They in turn had approached former ball player William T. "Sleepy Bill" Burns, who had connections to gamblers, and Billy Maharg, who had connections to gamblers at the underground level. Eventually the cost to throw the game would be $100,000 split between the players, with Arnold Rothstein, a man who had connections to organized crime, to provide the funding. [3] According to author Eliot Asinof, Cicotte also had personal reasons for the fix: he was promised a $10,000 bonus in his contract for getting 30 regular season wins, but was benched by Comiskey soon after his 29th, allegedly to avoid paying it.

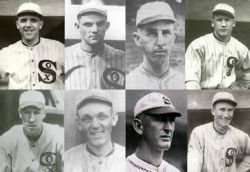

The eight players[edit]

- Eddie Cicotte, pitcher.

- Arnold "Chick" Gandil, first baseman.

- Claude "Lefty" Williams, pitcher.

- Oscar "Happy" Felsch, centerfielder.

- Charles "Swede" Risberg, shortstop.

- George "Buck" Weaver, third baseman.

- Joseph Jefferson "Shoeless Joe" Jackson, left fielder.

- Fred McMullin, utilityman.

Of the players, McMillan overheard conversations regarding the fix and wanted in, making a threat to inform Comiskey if he wasn't. Weaver sat in on details of the fix but did not participate in it at all. Cicotte asked for, and received, $10,000 up front, finding it in his hotel room the night of Game 1.

Joseph Jefferson Jackson was considered by many to have been the greatest ball player of his time, with a third-highest batting average of .356; his .400 average in his first year of professional baseball was the highest for a rookie. His special bat was hand-made from a plank of hickory nearly four feet long, and stained black from various coatings of tobacco juice. Babe Ruth was said to have modeled his own power hitting on Jackson who, he said, "had a special crack to it." Shoeless Joe was discovered in the minor leagues playing one game in his socks because his new cleats were too tight; a fan shouting an offensive epithet would give him his nickname.

The World Series[edit]

Game 1[edit]

Before the Series had opened, Chicago was heavily favored, but by the end of September, large amounts of money were changing hands as bets were cast in Cincinnati's favor by five-to-one odds. The 1919 World Series began October 1, 1919, in Cincinanati's Redland Field, and the pre-arranged signal to the gamblers that the fix was on was when Cicotte hit Reds batter Morrie Rath in the back with a fast ball at the bottom of the first inning. From that point on, play was sporadic with the Chicago players, as the players involved would play well one moment and play badly the next, frustrating the honest players not involved with the fix. For Cincinnati - completely unaware of the fix - Greasy Neale and Jake Daubert would lead the team in hits, and pitcher Dutch Ruether would allow only six from the White Sox to get on base.

| Game 1, October 1, 1919, Redland Field, Cincinnati, Ohio | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

Game 2[edit]

Cincinnati would win again, with Reds players Slim Sallee pitching and Larry Kopf gaining a two-run triple in the fourth inning. As to getting paid by the gamblers, only Cicotte had got his money.

| Game 2, October 2, 1919, Redland Field, Cincinnati, Ohio | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

Game 3[edit]

Starting for game 3 was rookie Dickey Kerr, a White Sox pitcher who didn't hear from his fellow players about the scandal; he played like he meant to and gave Chicago its first victory.

The other players in the fix began to grumble about not being paid, and more so by the end of Game 3. Gandil received a mere $1,000 and distributed it among the players; Jackson would eventually be given $5,000.

| Game 3, October 3, 1919, Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

Game 4[edit]

Jimmy Ring of the Reds pitched a shutout.

| Game 4, October 4, 1919, Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

Game 5[edit]

Hod Eller of the Reds pitched a shutout. The players of the White Sox would realize that they were being hoodwinked by the gamblers; what little money came in was the total that would ever come in, so in the remaining games they would play to win.

| Game 5, October 6, 1919, Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

Game 6[edit]

| Game 6, October 7, 1919, Redland Field, Cincinnati, Ohio | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | R | H | E | |

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

Game 7[edit]

| Game 7, October 8, 1919, Redland Field, Cincinnati, Ohio | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

Game 8[edit]

In the final game the White Sox lost, and probably had no choice but to do it. At least one of the players involved in the scandal had received a threat against his wife if he didn't lose the game.

| Game 8, October 9, 1919, Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | R | H | E | ||

| Cincinnati Reds | |||||||||||||

| Chicago White Sox | |||||||||||||

Cincinnati won the Series by October 9, 5 games to 3.

Trial[edit]

In September 1920, as rumors piled up regarding the fixing of baseball games in general, and the 1919 World Series in particular, a grand jury was convened in Chicago to investigate. Both Jackson and Cicotte would confess, causing Comiskey to suspend the seven players of the fix still on his team (Gandil was already out of the majors). Their confessions, a key part of the trial, vanished from the Cook County Courthouse before the trial opened in June, 1921. Without the confessions, as well as a lack of evidence, all eight were acquitted on August 3.

Before the trial was even underway, baseball team owners got together to create a baseball commissioner, who would oversea baseball's integrity and restore public confidence in the sport. As a new commissioner they chose a retired judge, Kenesaw Mountain Landis [4], a no-nonsense jurist who once sent an old man to 16 years in prison for robbery. "Judge, I ain't got that much time left," the man protested. "Well, do the best you can," Landis replied.

On August 4, 1921, the day after the verdict in the Black Sox trial, and using the unlimited power granted to him by the owners, Landis set about correcting baseball's image, and the first act he did was public, decisive, and uncompromising:

- Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ball game, no player who undertakes or promises to throw a ball game, no player who sits in confidence with a bunch of crooked gamblers and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.

All eight players were banned for life. Subsequent letters protesting innocence and asking for reinstatement went unheeded, even Buck Weaver, whose guilt in the matter was very much in doubt, sent letters to the next six commissioners; each time he was turned down. "I had Weaver in my office," Landis said, "and I asked him if he sat in on the meetings." Weaver replied that he did, but that he never took part in the fix, stating that he played the best baseball he could. Analysis of baseball records indicate that he indeed did do just that. [5] But Landis would not compromise. "Son, you can't play ball with us anymore."

Seven of the eight players would find life in the minors, either in outlaw baseball or under assumed names, and taking ordinary, unassuming jobs after they were physically unable to play the game. Being banned from baseball meant that one of them, Jackson, whose guilt was also in doubt, would not be eligible for the Hall of Fame, as many of his records still stand. Like Weaver, baseball historians still dispute as to whether Jackson was or was not part of the actual fix. In the Series he was 12-for-32 with a .375 batting average, with 5 runs, 3 doubles, 1 home run and 6 RBI.

Charles Comiskey died in 1931. Four years after the trial was over, the missing confessions turned up in the office of Comiskey's lawyer; no one knows how they got there. Comiskey has had two baseball parks built for his team named after him, and he also has a plaque of honor in the Baseball Hall of Fame. [6]

References[edit]

- Asinof, Eliot. Eight Men Out, Henry Holt, New York (1963).

- Pietrusza, David Rothstein: The Life, Times and Murder of the Criminal Genius who Fixed the 1919 World Series, Carroll & Graf, New York (2004).

KSF

KSF