Yeoman

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 6 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 6 min

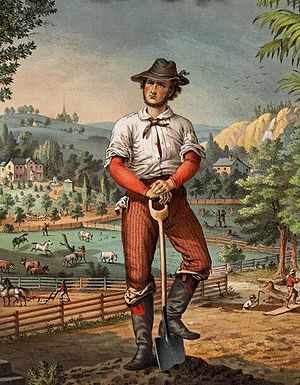

The Yeoman was the term for independent farmers in the U.S. in the late 18th and early 19th century. The yeoman have been intensely studied by specialists in American social history, and the history of Republicanism. The term fell out of common use after 1840 and is now used only by historians.

Yeomen in the South are often called Plain Folk of the Old South. They were the middling white Southerners of the 19th century who owned few slaves or none. They played a major role in the history of the Ante Bellum South, although they were less influential than the planters.

Historians have long debated the social, economic and political roles. Terms used by scholars include "common people", "yeomen" and "Crackers."

Contents

Republicanism[edit]

The term favored in Jeffersonian Democracy and Jacksonian Democracy was "yeoman", which emphasized an independent political spirit and economic self-reliance. Thomas Jefferson and John Taylor of Caroline in particular praised the yeomen as the carriers of America's Republican values. Jefferson warned that virtue could not long survive in the cities (or among dependent tenant farmers or slaves) because these people would be controlled or corrupted by others and lose their independence.Historian Richard Hofstadter traced the yeoman ideal in America's sentimental attachment to the rural way of life, which is 'a kind of homage that Americans have paid to the fancied innocence of their origins. To call it a 'myth' is not to imply that the idea is simply false. Rather the 'myth' so effectively embodies people's values that it profoundly influences their ways of perceiving values and hence their behavior. He stresses the significance of the writings of Jefferson and his followers in the development of agricultural fundamentalism. Hofstadter emphasized the importance of the agrarian myth in American politics and life even after industrialization had revolutionized the American economy and life. Indeed, American farmers into the 21st century identified themselves as yeomen with a superior claim to republican values., and looked down at the "corruption" they sensed in the nation's cities.[1]

South[edit]

From the travel accounts of Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1850s through the early-twentieth century interpretations of historians William E. Dodd and Ulrich B. Phillips common southerners were portrayed as minor players in the antebellum period. Romantic portrayals, especially Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind (1937) and its 1939 film ignored them. Novelist Erskine Caldwell's Tobacco Road, portrayed the degraded condition of whites dwelling beyond the great plantations.

The major challenge to the negative view came from historian Frank Lawrence Owsley in Plain Folk of the Old South (1949). His book and followup studies ignited a long historiographical debate. Owsley started with the writings of Daniel R. Hundley who in 1860 had defined the southern middle class as "farmers, planters, traders, storekeepers, artisans, mechanics, a few manufacturers, a goodly number of country school teachers, and a host of half-fledged country lawyers, doctors, parsons, and the like." To find these people Owsley turned to the name-by-name files on the manuscript federal census. Owsley's Plain Folk of the Old South, says Vernon Burton, is, one of the most influential works on southern history ever written. Using their own newly invented codes they turned into data bases the manuscript federal census returns, tax and trial records, and local government documents and wills. Plain Folk argued that southern society was not dominated by planter aristocrats, but that yeoman farmers played a significant role in it. The religion, language, and culture of these common people created a democratic "plain folk" society. Critics say he overemphasized the size of the southern landholding middle class while excluding the large class of poor landless and slaveless white southerners.[2] Owsley assumed that shared economic interests united southern farmers without considering the vast difference inherent in the planters' commercial agriculture versus the yeomen's subsistence life style.

In his study of Edgefield County, South Carolina, Orville Vernon Burton[3] classified white society into the poor, the yeoman middle class, and the elite. A clear line demarcated the elite, but according to Burton, the line between poor and yeoman was never very distinct. Stephanie McCurry argues, yeomen were clearly distinguished from poor whites by their ownership of land (real property). Yeomen were "self-working farmers," distinct from the elite because they worked their land themselves alongside any slaves they owned. Ownership of large numbers of slaves made the work of planters completely managerial.

From yeoman to redneck[edit]

After the Civil War the status of the yeomen fell drastically. Many became sharecroppers or tenants—they worked land owned by landowners in town. In the towns the rising southern middle class rejected the celebration of rural life associated with the yeoman. They denounced as "demagogues" the radical leaders who appealed to the poor farmers, for example "Pitchfork Ben Tillman who was governor and senator from South Carolina. As the poor Democrats endorsed lynching of uppity blacks, the middle class townsfolk denounced lynching in the name of Law and order. Some poor farmers moved to mill towns, especially to work in the textile mills of the Carolinas. The money was much better than on the hard-scrabble farms, but this again represented a fall in social status. By the end of the century the middle class was ridiculing the former yeomen as "rednecks" and "hillbillies."[4]

Self image of farmers[edit]

When Harry Truman's Secretary of Agriculture Charles Brannan in 1949 proposed a plan of direct assistance to small farmers, he justified it by reasserting the importance of the small family farmer as the foundation of American democracy. However, in the Grange small farmers opposed the plan because it too closely resembled welfare and would undermine their self-image as independent yeomen and successful entrepreneurs. Agribusiness used the same images to oppose it for its own reasons. Brannan sought to protect the small farmer against competition from the large companies, but the plan was not accepted by Congress because farmers self-image would not allow for welfare.[5]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Ash, Stephen V. "Poor Whites in the Occupied South, 1861-1865," Journal of Southern History, 57 (February 1991), in JSTOR

- Bolton, Charles C. "Planters, Plain Folk, and Poor Whites in the Old South," in A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction, ed. Lacy Ford (2005), 75–94.

- Bonner, James C. "Profile of a Late Ante-Bellum Community," American Historical Review, Vol. 49, No. 4 (Jul., 1944), pp. 663–680 in JSTOR

- Bruce Jr., Dickson D. And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain Folk Camp Meeting Religion, 1800-1845 (1974)

- Burton, Orville Vernon. In My Father's House Are Many Mansions: Family and Community in Edgefield, South Carolina (1985) online version

- Campbell, Randolph B. "Planters and Plain Folks: The Social Structure of the Antebellum South," in John B. Boles and Evelyn Thomas Nolen, eds., Interpreting Southern History(1987), 48-77;

- Carey, Anthony Gene. "Frank L. Owsley's Plain Folk of the Old South after Fifty Years," in Glenn Feldman, ed., Reading Southern History: Essays on Interpreters and Interpretations (2001)

- Cash, Wilbur J. The Mind of the South (1941), an old classic excerpt and text search

- Flynt, J. Wayne Dixie's Forgotten People: The South's Poor Whites (1979). deals with 20th century.

- Cecil-Fronsman, Bill. Common Whites: Class and Culture in Antebellum North Carolina (1992)

- Forret, Jeff. Race Relations at the Margins: Slaves And Poor Whites in the Antebellum Southern Countryside (2006) excerpt and text search

- Hahn, Steven. The Roots of Southern Populism: Yeoman Farmers and the Transformation of the Georgia Upcountry, 1850-1890 (1983) excerpt and text search

- Harris, J. William. Plain Folk and Gentry in a Slave Society: White Liberty and Black Slavery in Augusta's Hinterlands (1985)

- Hyde Jr., Samuel C. "Plain Folk Yeomanry in the Antebellum South," in Boles, ed., Companion to the American South, 139-55.

- Hyde Jr., Samuel C. ed., Plain Folk of the South Revisited (1997).

- * Hyde Jr., Samuel C. "Plain Folk Reconsidered: Historiographical Ambiguity in Search of Definition" Journal of Southern History (Nov 2005) vol 71#4

- Hundley, Daniel R. Social Relations in Our Southern States (1860; reprint 1979) online edition

- Linden, Fabian. "Economic Democracy in the Slave South: An Appraisal of Some Recent Views," Journal of Negro History, 31 (April 1946), 140-89 in JSTOR; emphasizes statistical inequality

- Lowe, Richard G. and Randolph B. Campbell, Planters and Plain Folk: Agriculture in Antebellum Texas (1987)

- Osthaus, Carl R. "The Work Ethic of the Plain Folk: Labor and Religion in the Old South." Journal of Southern History (2004) v. 70#4, 745-82.

- McCurry, Stephanie. Masters of Small Worlds: Yeoman Households, Gender Relations, and the Political Culture of the Antebellum South Carolina Low Country (1995),

- McWhiney, Grady. In Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South (1988)

- Morgan, Edmund S. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (1975). online edition

- Newby, I. A. Plain Folk in the New South: Social Change and Cultural Persistence, 1880-1915 (1989). concentrates on the poorest whites

- Otto, John Solomon. "The Migration of the Southern Plain Folk: An Interdisciplinary Synthesis," Journal of Southern History, 51 (May 1985), 183-200. in JSTOR

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence. Plain Folk of the Old South (1949), the classic study

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence. with Harriet C. Owsley, "The Economic Basis of Society in the Late Ante-Bellum South," Journal of Southern History 6 (Feb. 1940): 24-25, in JSTOR

- West, Stephen A. From Yeoman to Redneck in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1850–1915. (2008), 262pp

- Woodward, C. Vann. Tom Watson: Agrarian Rebel (1938). online edition classic study of leader of plain folk in Georgia

- Wright, Gavin. "'Economic Democracy' and the Concentration of Agricultural Wealth in the Cotton South, 1850-1860," Agricultural History, 44 (January 1970), 63-93 in JSTOR, a statistical critique of Owsley

notes[edit]

- ↑ Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (1955).

- ↑ Hyde (2005)

- ↑ Burton (1985)

- ↑ "Redneck" refers to being sun-burned from worked in the hot fields. "Hillbillies" lived in remote mountain areas. Stephen A. West, From Yeoman to Redneck in the South Carolina Upcountry, 1850–1915. (2008)

- ↑ Karen J. Bradley, "Agrarian Ideology and Agricultural Policy: California Grangers and the Post-world War II Farm Policy Debate," Agricultural History 1995 69(2): 240-256, in JSTOR

KSF

KSF