Biogeography

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 29 min

From RationalWiki - Reading time: 29 min

| We're all Homo here Evolution |

| Relevant Hominids |

| A Gradual Science |

| Plain Monkey Business |

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species due to evolutionary history. It is a powerful argument for evolution and a branch of evolutionary biology.

The Wallace Line[edit]

The Wallace line, drawn by Alfred Russel Wallace, marks the point of separation between Asian-like and Australian-like fauna and the maximum westward spread of marsupials.[1] For example, the areas to the west of the line are dominated by placental mammals, while those to the east are marsupial-dominated. This is due to the fact that, during one of the ice ages, the continental shelves of the Asian and Australian landmasses extended farther than they do now, while still being separated by a large amount of water.[2] Therefore, marsupial mammals from Australia colonized areas such as New Guinea, while placental mammals from Asia colonized western Indonesia. The separation of marsupial and placental lineages, therefore, dates to before Laurasia (the supercontinent modern Asia developed from) and Gondwana (the supercontinent Australia separated from) separated. Plants also follow the Wallace line, although not to such a great extent, and their distributions in the area around the line also provide strong support to the idea that Asia and Australasia were separated for long periods of time.[3] In addition, monotremes also occur only east of the line.[4]

The situation with birds is slightly more complicated, due to the fact that most have the power of flight. However, trends can still be seen. For example, cockatoos (Cacatuidae) occur only east of the Huxley line, except for the island of Palawan.[5][6]

Similarly, ratites (flightless paleognaths) occur only east of Wallacea. Populations in Wallacea are introduced.[7][8][9][10][11] Additionally, the four ratites of Australia and Papua New Guinea (the three species of cassowary, as well as the emu Dromaius novaehollandiae) form a monophyletic clade. There is however, disagreement over whether this clade forms a family (Casuariidae) an order (Casuariiformes) or a subgroup within the order Struthioniformes.[12][13][14]

Taxa that cross the Wallace Line[edit]

True monitors (Varanidae) are a widespread family of lizards that live from southern Africa to Australia.[15] Around half of its species live in Australia, which means that the geographical center of their distribution is around Wallacea. True monitors are an old group, being at least 65 million years old by most estimates.[16] They are also highly capable swimmers,[17][18] meaning that they would have had no problem dispersing over water.

Due to their distribution patterns, we would expect that the Varanidae originated some place around Wallacea (which would explain how they managed to cross it so well). If so, the closest living relative of the Varanidae should live in the area.

This is exactly what we see. That closest relative, the Bornean earless monitor lizard, lives slightly west of the line, on the island of Borneo.[19][20]

The Coturnix genus of Old World quail also crosses the Wallace Line. While its most well-known members occur in Eurasia,[21][22][23] it has two members in Australia (the stubble quail and brown quail).[24][25][26] In addition, a recently extinct member of the genus used to live in New Zealand, having gone extinct by 1875.[27][28]

While most incubator birds (Megapodiidae) range east of the Wallace Line in Australasia, several occur west of it, including in the Philippines.[29][30] One species, the Nicobar megapode Megapodius nicobariensis, even lives as far west of the line as the Nicobar Islands in the eastern Indian Ocean, northwest of Sumatra.[31][32]

In conclusion, those taxa that cross the Wallace Line are those that are comparatively ancient and/or able to cross water, generally birds capable of flight.

Additional terminology[edit]

Lydekker's line, drawn by Richard Lydekker,![]() is the line of maximum expansion of Asian mammals into Indonesia.[33]

is the line of maximum expansion of Asian mammals into Indonesia.[33]

Weber's Line, drawn by Max Carl Wilhelm Weber,![]() marks the boundary between Oriental fauna-dominated areas to its west and Australian fauna-dominated areas to its east.[34]

marks the boundary between Oriental fauna-dominated areas to its west and Australian fauna-dominated areas to its east.[34]

Wallacea is the area between Wallace's and Lydekker's line.[35]

Huxley's Line is a revision of the Wallace Line by Thomas Henry Huxley, altering the northern segment of the latter line to go west of the Philippines (excluding the island of Palawan) instead of east of it, due to the Philippines' unique flora and fauna.[36]

Gondwana[edit]

Gondwana was an ancient supercontinent which incorporated the areas of land that today comprise South America, Australia, Africa/Arabia, Antarctica, and India.[37] It began breaking up during the Mesozoic Era.[38] Unlike with Laurasia, there has been far more limited movement by species across its areas since its split split, due to the fact that basically all of the latter was connected by the Bering Land Bridge during recent ice ages.[39][40] Therefore, its animals provide the most widely used and most convincing examples of relict distributions used to demonstrate how the evidence proves evolution.

Paleognathae[edit]

The paleognaths are a suborder of birds.[41] A ratite is any paleognath bird that is also flightless.[42][43] They also, apparently, have delicious red meat.[44] Paleognaths likely flew into formerly Gondwanan areas from the north, then lost flight multiple times, in a stunning example of convergent evolution. This is due to the fact that ratites are paraphyletic, with the flying tinamous nested within them instead of being a sister group.[45] Paleognaths currently occur in the Gondwanan landmasses of Africa/Arabia, New Zealand, Australia, and South America.[46] Extinct members also lived in India,[47][48] Madagascar,[49][50][51] and Antarctica.[52][53]

Early paleognaths, such as the lithornithids![]() were typically Laurasian in distribution and capable of flight. They ranged over Europe and North America.[54] Lithornithids were basal lineages among the paleognaths, meaning members among them flew south and colonized formerly Gondwanan areas.[55][56] Due to this, the phylogeny of paleognaths follows a different pattern from that which would be expected if paleognaths had originated in Gondwana, and the splitting apart of their lineages was caused by the drifting apart of its component continents.[57]

were typically Laurasian in distribution and capable of flight. They ranged over Europe and North America.[54] Lithornithids were basal lineages among the paleognaths, meaning members among them flew south and colonized formerly Gondwanan areas.[55][56] Due to this, the phylogeny of paleognaths follows a different pattern from that which would be expected if paleognaths had originated in Gondwana, and the splitting apart of their lineages was caused by the drifting apart of its component continents.[57]

Austral conifers[edit]

The austral or southern conifers are two conifer families (Araucariaceae and Podocarpaceae) whose distribution is mainly south of the Equator and whose distributions can be easily explained by continental drift.[58][59][60][61][62][63][64] Fossils of the Araucariaceae date back to the Triassic.[65]

During the Mesozoic Era, the Araucariaceae had a far wider distribution, as far north as England and Japan, which is explainable by Gondwana being part of Pangaea at the time.[66][67] The Podocarpaceae similarly date back to the Mesozoic, also to the Triassic period.[68] They also had non-Gondwanan representatives during the Mesozoic Era, although not to such a great extent as the Araucariaceae, but, unlike the former group, expanded in the Cenozoic, such that their range is currently far larger.[69] In fact, podocarps currently range as far north as Japan and Mexico, both of which are decidedly Laurasian.[70]

Many Araucariaceae, such as the Wollemi Pine, are considered "living fossils".[71] Unsurprisingly, creationists are attempting to use this as "proof" against evolution. ICR, for example, claims that the Wollemi Pine somehow poses an "evolutionary mystery" for scientists.[72] Obviously, this is wrong, for several reasons:

- Mesozoic fossils show that the Araucariaceae had already split into distinct branches by the Triassic. This blatantly contradicts the creationist model of rapid post-Flood speciation and diversification. In fact, it portrays a beautifully illustrated story of slow, pleasantly uniformitarian change.

- The fact that there is basically no difference between Agathis jurassica and Wollemia nobilis blatantly contradicts the baraminological model, under which species rapidly "degenerate" and change is rapid.

- Wollemi pines do not necessarily require the conditions of their home canyons to grow. They have, for example, been raised in cultivation.[73]

- Even if modern Wollemi pines are adapted to canyon conditions, it does not follow that their ancestors were. A. jurassica, for example, lived outside the canyon area. Species adapt. Therefore, it is not necessary for the canyons to have been around for the Wollemi pine to have survived.[74]

- Dilwynites pollen has been found in South America in rocks dated as late as the Middle Eocene, specifically 46 mya. 46 million and 150 million years are wildly different dates, which shows ICR's blatant dishonesty.[75]

- Fossils of the Wollemi Pine have been found in rocks just two million years old in Tasmania. Given the near-continuous fossil record of these trees since the Mesozoic, and their small range, in hard-to access areas, it is in no way unusual that a plant whose most recent fossils are two million years old should still be living.[76]

In conclusion, ICR is misrepresenting facts and blowing hot air, and the evidence is far more hostile to creationism than to evolution.

Parasitaxus usta, the world's only parasitic conifer, is a podocarp from New Caledonia.[77]Its host is the fellow podocarp Falcatifolium taxoides.[78] The rate of genetic change of the chloroplasts of Parasitaxus was higher than normal, likely due to a new food source, from another plant instead of from sunlight.[79] The closest relatives of Parasitaxus are likely Lagarostrobos (Huon pine) and Manoao.[80] P. usta uses fungi in order to receive nutrients from its host.[81][82] Creationists have not even tried to explain how these features and apparatuses could have evolved in 6,000 years due to "degeneration" from an original podocarp "archaebaramin". In fact, such a development is blatantly impossible, providing even more proof against creationism and in support of evolutionary theory.

Interestingly, podocarp success in the face of competition with angiosperms has been linked to their large, wide leaves, with wide-leaved lineages generally being more successful and widespread. This trend is noticeable in the fossil record, particularly in the Cenozoic.[83] This trend, with the expansion and reduction of lineages being illustrated in the fossil record, culminating in their modern distribution, exactly matches the distribution expected of evolution and does not match the distribution expected from creationism.

Lungfish[edit]

Lungfish (Dipnoi) are a group of air-breathing lobe-finned fish that are spread across the southern continents.[84] They currently occur in South America, Africa, and Australia. Their fossils date from the early Devonian period. Lungfish lungs are similar to those of amphibians, and their fins provide a model for how primitive tetrapods could have walked on land.[85]

Interestingly, the hatchlings of the Australian lungfish are impossible to tell apart with the naked eye from those of salamanders.[86] This is a useful piece of information to present cretinists with when they ramble on and on about "fishapods". In fact, an even more effective approach would be to present them with photographs of the hatchlings in question and request that they sort them into "kinds". Since, according to creationism, "kinds" are clearly and sharply delineated, they should have no problems with this simple task. Meanwhile, keep notes on which of the photos belong to which species, and confront them with that after they would inevitably fail to properly distinguish the "kinds" in question.

Fossil lungfish burrows have been found as early as the Permian, indicating their lifestyles were similar to those of today even back then. During the Mesozoic, they, like so many other groups on this page, had a far larger distribution, being distributed nearly worldwide. In addition, the still-extant genus Neoceratodus was already around back then.

While under creationism, the lungfish-amphibian similarity is mysterious, under evolutionary theory, it makes perfect sense. Lungfish are the closest living relatives of tetrapods, and should therefore be expected to look a lot like basal tetrapods (e.g., amphibians). This prediction is borne out by the evidence.

Marsupials[edit]

Marsupials (Marsupalia) are a group of mammals characterized by premature birth (compared to placental mammals), with the neonates then being transferred to pouches.[87] Marsupials were formerly more common in the Mesozoic, but now are generally restricted to the southern continents, specifically South America and Australasia.[88][89]

The term Metatheria refers to all mammals that are more closely related to marsupials than to placental mammals, as well as the marsupials themselves. The group was proposed by Huxley in 1880.[90][91] Metatherians are often confused with the less-broad group of marsupials, likely due to true marsupials being the only extant group of metatherians.[92] Metatherians originally evolved in Laurasia, but the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event and competition with placental mammals reduced their range and numbers, causing them to become extinct there. Eventually, most of their fossils came to be found in Gondwanan areas.[93]

Marsupials evolved in Laurasia and spread from North America to South America over a land bridge.[94] They had diverged from placental mammals by the Middle Cretaceous.[95] Laurasian marsupials went extinct in the Paleogene due to competition with placental mammals.

Kurt Wise, in his book Explore Evolution, wrote a comically bad attempt at at disproving evolutionary theory and debunking the relevance of marsupials within the realm of biogeographical evidence for evolution, while also confusing Australian possums and American opossums, and strawmanning extensively. NCSE has published an elegant and concise refutation of his claims.[96]

The subgroup Australidelphia within the marsupials occurs mostly in Australasia. However, it contains one South American member, the monito del monte, which is basal to the rest.[97] This, combined with the paleontological evidence and the fact that all non-Australidelphian marsupials (which form a paraphyletic group known as the "Ameridelphia") occur in the Americas, supports the hypothesis that marsupials spread from South America to the rest of their range.[98][99]

Interestingly, the Didelphidae, among whose members are the only non-Gondwanan marsupials, have been shown to have dispersed north over the Isthmus of Panama after its formation.[100][101] The closest relative of the North American opossum is a Mexican species, meaning both likely evolved from a common ancestor that migrated north over said isthmus.[102] Therefore, vicariance is supported even more strongly, by the fact that phenomena that seem to be exceptions to the pattern of vicariance actually provide even more support to the hypothesis.

It conclusion, marsupial range can be summarized as those areas reachable and habitable by mammals where placental mammals are not. For example, Antarctic marsupials died out due to the cold, and African ones due to competition (South America being a minor exception). The same occurred throughout Laurasia. The absence of marsupials from Gondwanan New Zealand is likely due to to its inaccessibility. Note that the creationist explanation, which has rafting as the major means of post-Flood transport, would imply that land mammals, specifically marsupials, should be native to there. Yet they are not. The inhospitability of the New Zealand environment cannot be a factor, since introduced land mammals, such as stoats and rats, have multiplied to the point of causing significant ecological damage there when they have managed to get there.

Nothofagaceae[edit]

The Nothofagaceae or southern beeches are a group of plants that occur throughout the southern continents. Their seeds are easily damaged by seawater, showing that they could not have rafted over the ocean, as creationist theory suggests, which supports the idea that their distribution is due to continental drift.[103] They formerly had a far wider range, however, there is no fossil record of them from Africa or India, in line with the view that those continents were the first to split from Gondwana.[104] Additionally, what seem to be contradictions between the vicariance model and the fossil pollen evidence have already been resolved by postulating extinction of several lineages.[105] The leaf shapes of their fossil members reflects the climate of the times, and the low variation in said shapes provides good evidence against the changes expected in baraminology.[106] Additionally, the fact that leaves adapted to significantly different climactic conditions occur in the same place prove that the relevant fossils cannot have lived at the same time, providing compelling evidence against a young-Earth model.

Preserved Antarctic fossils show that members of the Nothofagaceae, which even today include many members well-adapted to tundra conditions, were among the last vascular land plants to occur in Antarctica, going extinct around there 15 mya.[107]

Fossils of the Oligocene/Miocene Nothofagus palustris provide data on the evolution of leaf wax within the Nothofagaceae. Again, we see trends in the fossil record occurring slowly over time.[108]

Parastacidae[edit]

The Parastacidae are a family of crawfish found throughout the Southern Hemisphere, in Madagascar, South America, and Australasia, with their greatest diversity in Australia.[109] They are remarkable in the extent to which they are restricted to the southern continents, with only one known Laurasian member, Aenigmastacus crandalli from the Eocene of British Columbia. Its ancestors likely traveled there through Asia.[110]

Genetic evidence has been used to show that Australian parastacids are paraphyletic, and the descendants of their most recent common ancestor was also the ancestor of the parastacids of Madagascar and New Zealand, with the New Zealand and Madagascar species forming a clade with two genera from Tasmania, as well as showing that New Zealand has never been completely submerged since parastacids reached it (hint, hint).[111]

Additionally, those same biogeographic methods also work when applied within lineages and even genera.[112] In some cases, they even make up for a lack of fossil evidence illustrating divergences.[113] In many cases, they also illustrate speciation as early as the Miocene, as well as providing new tools for which to classify species.[114] Said studies also illustrate that vicariance can be a powerful method and model of speciation, while also providing real-world examples of punctuated equilibrium, as well as explanations for its causes.[115] They also show that, consistent with uniformitarian theories of plate tectonics, the Astacoides of Madagascar are the most basal living parastacids.[116]

Osteoglossiformes[edit]

The Osteoglossiformes are an old, morphologically diverse order of ray-finned fish whose distribution can easily be explained by vicariance, as long as it is assumed that crown-group teleosts date back to the Paleozoic, an assumption which is supported by the molecular and genetic evidence. Vicariance is the likely cause for the separation of the African Heterotis and South American Arapaima lineages within the Arapaimidae.[117]

Old World knifefish (Notopteridae) include two clades, one composed of their African representatives, and one composed of its Asian species. Data confirms that osteglossiform fish had a Gondwanan origin in the Early Triassic, thus making it obvious that teleosts originated before that, in the Paleozoic, consistent with earlier predictions. Fossil data also shows that Osteoglossiformes are an ancient group of primarily freshwater fish (primarily meaning their most recent common ancestor lived in freshwater, not that most of its species live in freshwater, even though, strictly speaking, that is also true), while tests show that modern notopterids are generally intolerant of salinity, with only one species being able to tolerate low levels of it (which would still be less than those encountered in oceanic environments.) All of this shows the notopterids cannot have dispersed across saltwater, making vicariance the most likely hypothesis.[118]

Fossil data shows that the Arapaimidae were formerly more widespread. Its two living genera diverged 50 to 80 million years ago.[119] The Arapaimidae diverged from their closest relatives, the Osteoglossidae (arowanas) around 220 million years ago. Meanwhile, the Asian and Australian branches of the Osteoglossidae diverged around 140 million years ago, with the Asian branch likely traveling there through Gondwanan India.[120] Molecular data shows the Osteoglossidae to be divided into two clades, one (Osteoglossum species) from South America and the other (Scleropages species) from Asia and Australasia.

Interestingly, the Osteoglossidae are the only exclusively freshwater fish family to occur on both sides of the Wallace Line.[121] This is likely due to their massive age as a distinct family/taxon. The South American and Australasian branches of the Osteoglossidae diverged around 170 million years ago in the Middle Jurassic, allowing the ancestors of the modern Asian arowana to be carried to the Indian subcontinent after the Sclerophages branch split, meaning their route to Asia was not blocked by saltwater.[122]

The Osteoglossidae, like the arapaimas, were also formerly more widespread, with Phareodus even being known from the Eocene of Wyoming's Green River formation.[123] Notably, Phareodus had an appearance quite unlike modern osteoglossids, instead looking quite like modern members of the Hiodontidae, which form the sister group to the Osteoglossiformes.

Osteoglossiform monophyly is beyond doubt. The following features are shared among the Osteoglossiformes and their closest relatives, the mooneyes, who are sometimes included in the order (the two taxa form the "Osteoglossomorpha"):[124][125]

- Primary bite between parasphenoid and tongue.

- Absence of supramaxillary bone.

- Absence of supraorbital bone.

- Fusion of fourth and fifth infraorbital bones.

- Number of epural bones decreased to one or zero.

- 18-17 or fewer principal caudal fin rays.

- Paired tendon bones on 2nd hypobranchial (in extant species).

- Intestine passes to the left of the stomach (in extant species).[126][127]

- Tongue used as opposing surface for teeth; bony, toothed tongue, teeth on roof of mouth.

- Rudimentary caudal skeleton.[128][129]

Common features are also visible within lineages within the order, such as:

- Air-breathing capability in basal lineages (Osteoglossoidei).[130] Osteoglossidae and Arapaimidae even have a suprabranchial organ for the purpose. The arapaima Arapaima gigas is actually an obligate air-breather.[131] This has led to it being vulnerable to human spearfishing, causing it to become extirpated in many areas, a prime example of suboptimal design, since many Amazonian fish can survive without breathing air.[132] The African knifefish and some notopterids can also breathe air, although the Mormyridae (elephantfishes), the most derived osteoglossiforms, cannot.

- Ability to generate electricity within the clade composing the Gymnarchidae and Mormyridae. These two families are also the only vertebrates to have spermatozoa lacking flagellae.[133]

- Upper and lower parts of ear are completely separated in the more derived Notopteroidei suborder.[134]

The closest relatives of the Osteoglossiformes are the Hiodontidae (mooneyes), who are sometimes included within the order. They are not Gondwanan, instead living near the United States-Canada border.[135][136] This geographical data, combined with molecular tests to determine relatedness, can be used to determine when and where the two lineages split from a common ancestor, as well as providing a calibration to confirm the likely date of the breakup of Pangaea.

Galaxiiformes[edit]

The Galaxiiformes are an order of freshwater and anadromous fish living throughout the temperate parts of the Southern Hemisphere. They range throughout Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, and the southern tips of Africa and South America.[137] Fossils are recorded from the Miocene of New Zealand (23 mya) of at least three species of Galaxias, with one of the two bearing a striking similarity to a living species of the genus. They were lake-living, likely indicating a freshwater origin for their order, which in turn argues against oceanic dispersal and for a dispersal based on continental drift.[138] There is no galaxiiform fossil record outside of Gondwana, nor do they currently occur outside of it..

Clariidae[edit]

Proteaceae[edit]

The Proteaceae (proteas) are a family of flowering plants distributed throughout the Southern Hemisphere, especially southern Africa, Australasia, and Madagascar, although South America, India, Indonesia, mainland Southeast Asia, and New Zealand also contain a few species.[139][140][141] In the New World, members of the family range as far north as Mexico. One of the Proteaceae's Neotropical genera, Orites, also occurs in Australia, suggesting the genus already existed when the two areas separated.[142]

Interestingly, the radiation of the subtribe Embothriinae, which is generally bird-pollinated, dates to around the time of the hypothesized origin of nectar-feeding birds in Australia. This is an interesting example of how fossil data can be used to confirm hypotheses about radiations for which fossils do not exist.

The Proteaceae are probably around 118 million years old, older than the breakup of Gondwana.[143] One genus, Beauprea, which is currently endemic to New Caledonia, formerly also occurred in New Zealand. It is likely around 88 million years old as a genus. The two islands were formerly joined as parts of a continent called Zealandia, most of which is now submerged. New Zealand has never been submerged since the Upper Cretaceous, meaning that most of its flora (and fauna) are Gondwanan in origin.[144]

Despite the fairly clear Mesozoic origin of the Proteaceae, the family has been the victim of an unfortunate bit of bad science led by Harry Levin, who has theorized that the group dates from the Carboniferous. While his work is admirably detailed, it sadly relies on shaky and bad assumption, such as miscalculating the date of the splitting of Gondwana.[145] His work has been extensively analyzed and refuted on Wikipedia's page on the subject.[146]

Cichlidae[edit]

Atherospermataceae[edit]

Tryonicidae[edit]

Eleotridae[edit]

Cunoniaceae[edit]

Karakas (Corynocarpus)[edit]

Laurasia[edit]

Calycanthaceae[edit]

Acipenseriformes[edit]

The Acipenseriformes (sturgeons and paddlefish) are an ancient order of primitive ray-finned fish living in the Northern Hemisphere. They are mostly freshwater fish and have skeletons mostly composed of cartilage.[147] Fossils of basal acipenseriform fish (Chondrosteidae) date back to the early Jurassic.[148] Chondrosteid appearance was remarkably similar to that of modern sturgeons.[149]

Currently, sturgeons range over a wide area as far south as the Gulf of Mexico.[150] Paddlefish, meanwhile, have a far smaller range, living only in North America and in China's Yangtze river.[151] The Chinese species is now almost certainly extinct and has been declared as such.[152][153][154] However, paddlefish previously had a far wider range, including west of the Continental Divide of the Americas![]() notably from the Eocene of Wyoming's Green River Formation

notably from the Eocene of Wyoming's Green River Formation![]() , where they now occur only east of it, and in a larger area in Asia than in recent times.[155][156][157][158]

, where they now occur only east of it, and in a larger area in Asia than in recent times.[155][156][157][158]

Magnoliaceae[edit]

The magnolias and tulip trees (Magnoliaceae) are an ancient family of broadleaved trees found mostly in the Northern Hemisphere, probably dating back to around 100 million years ago.[159] They currently occur in the Americas,the eastern parts of Asia, and in and around New Guinea.[160] Based on its current distribution and knowledge of its origin there, it has been possible to make predictions that the family once had a more extensive range in Laurasia.[161] This prediction is borne out by the evidence, with Miocene fossils of the family in Europe and extending further west within Asia.[162]

While the circumstance of magnolias ranging into Gondwanan territory may seem to pose a biogeographical problem, it does not, and in fact is a good illustration of the way taxa spread over time. Magnolias south of the Isthmus of Panama only date back to the biotic interchange over that same isthmus described elsewhere in this same article.Tellingly, Caribbean and South American magnolias are generally closely related (the islands of the Caribbean were and are part of the "southern" American ecozone, as shown on the interchange map.)[163] Those in New Guinea, meanwhile, are located near a major center of magnolia diversity in Southeast Asia which includes Indonesia to the west of the Sahul.[164] Magnolia seeds are known to be dispersed by birds and thus the comparatively narrow straits between the islands of Indonesia would not have been hard to cross.[165][166] Many magnolias (and their seeds) are also known for being highly salt tolerant, meaning their seeds could potentially been blown across the narrow seas of Indonesia.[167][168]

It is curious that magnolias, unlike most flowering plants pollinated by animals, are pollinated not by bees, but by beetles, with special adaptations in the flowers for that purpose, reflecting that beetles, unlike bees, pollinate flowers by crawling through them rather than landing on them. Bees and moths are, indeed, highly ineffective at pollinating magnolia flowers, and often get trapped in them, sometimes with fatal results.[169] Magnolias are, as said before, an extremely old family of flowering plants, and beetles are known to have been pollinators before bees.[170] Significantly, most or all of the families within the magnolia order (Magnoliales![]() ) are primarily beetle pollinated, such as the Annonaceae (custard-apples), the largest family within the order, and the Myristicaceae(nutmeg and relatives).[171][172][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180]

) are primarily beetle pollinated, such as the Annonaceae (custard-apples), the largest family within the order, and the Myristicaceae(nutmeg and relatives).[171][172][173][174][175][176][177][178][179][180]

In paleontology[edit]

The combination of biogeography with paleontology, known as paleobiogeography, can be used to determine the layout of prehistoric landmasses, as well as sea levels and other features.[181]

It can also be used to clarify relationships among taxa and provide additional information on evolution.[182] In addition, consilience between cladistic phylogeny and biogeographic trees provides additional support for the accuracy of using paleontology to reconstruct evolutionary trees.[183]

Fossil data has been used to measure the sea levels of million of years ago.[184] In many cases, fluctuations in those sea levels can also be measured.[185] The application of these methods of measurement can even be used to predict future changes in sea levels.[186] These methods can even be used to better understand prehistory.[187] In addition, fossil patterns can be observed to glean information on what geographic pressures existed in a certain area in a certain time.[188] It can even be used to provide data on population fluctuations, extinctions, and directions of movement of different species.[189] Many geological features span across now-disconnected continents, suggesting they were once connected.[190]

These methods can also be used to show that sea levels were stable during the last interglacial period, providing more evidence that current rises in sea levels are not normal and almost certainly anthropogenic.[191]

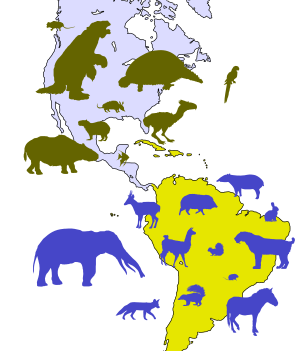

Great American Interchange[edit]

The Great American Interchange![]() began around 3 million years ago when the Isthmus of Panama

began around 3 million years ago when the Isthmus of Panama![]() formed and connected the continents of North and South America.[192] It involved the exchange of flora and fauna between North and South America, although far more migrated south than north. The formation of the isthmus also caused climate changes, such as turning the highlands Mesoamerica into a tropical rainforest, where earlier they had been semi-temperate dry forests dominated by plants such as walnuts (Juglans) and elms (Ulmus).[193]

formed and connected the continents of North and South America.[192] It involved the exchange of flora and fauna between North and South America, although far more migrated south than north. The formation of the isthmus also caused climate changes, such as turning the highlands Mesoamerica into a tropical rainforest, where earlier they had been semi-temperate dry forests dominated by plants such as walnuts (Juglans) and elms (Ulmus).[193]

It lead to the extinction of taxa such as terror birds (Phorusrhacidae) and notoungulates.[194][195]

The presence of stages of migration, with the first immigrant species in the areas affected being first found in strata more recent than in the areas they came from, is good evidence for the accuracy of radiometric dating and of evolution.

This is because:

- The migration of the animals can be divided into stages. Extinctions were positively correlated with migration levels.[196] Animal movements can also be tied to changes in vegetation and climate that are visible in the fossil history of Central America.[197]

- Under creationist theory, we should not expect this correlation of dates and stages of migration. Since, according to creationist flood pseudogeology, the time of death had no effect on fossil placement in rock strata since all the organisms supposedly died at nearly the same time, we should expect the fossil arrangements to be disordered and not to see organisms adapted to different climactic conditions in the same place. However, we see strata associated with different climates in the same area, with changes visible in those said layers. We also see that those animals predicted by biogeography to be "northern" (such as camelids, felids, canids, deer and elephantids) are first found in layers dated older in North America than in South America, while the opposite is true of "southern" animals (such as marsupials, tinamous and cavimorph rodents).Additional evolutionary predictions about the events have also been confirmed.[198] Such patterns contradict creationist predictions and thus refute the positions and assumptions used in order to make them.

In a similar situation to that of the Wallace Line, Wallace was also the first to comment on it, making conjectures on what is now referred to as the Interchange in his book, "The Geographical Distribution of Animals". In that book, he proposed certain ideas that are now part of scientific orthodoxy, such as the idea that the isthmus was formerly submerged under a sea, which previously formed a barrier between the two continents of the New World, and that glaciation changed the climate in the region and contributed to species movements.[199]

Another impact of the formation of the isthmus is that the marine populations on both sides of it were divided by the land and prevented from interbreeding. Porkfish and snapping shrimp are among the groups whose populations were split by the isthmus and who developed into separate species by allopatric speciation.[200][201]

Creationist responses[edit]

Creation Ministries International (CMI) claims biogeography, in the sense that Asian and American species are remarkably similar, refutes evolutionary theory.[202]

There are, obviously, several problems with their reasoning (there are always problems with their reasoning).

- CMI incorrectly defines species, claiming that two organisms that can interbreed are demonstrably the same species, while "species" is an exclusive grouping (if two populations cannot interbreed, they are different species, but if they can, that does not make them the same species.)

- CMI claims the relevant species did not evolve, but the fact that speciation occurred demonstrates that they did, in fact, evolve.

- The Modern Synthesis does not necessarily claim that rates of evolution are constant between or across lineages (see punctuated equilibrium).

- One can probably not think of any species whose appearance has changed as much in the past 6-million years as that of humans. In light of this, CMI's use of humans as a comparison is blatant cherry-picking.

- Phenotypic and genotypic evolution rates are not necessarily proportional.[203][204][205][206][207]

- Creationism has an even harder time explaining this (not that its supporters actually attempt to do so.) Under the massive mutation rates proposed by baraminology, East Asian and Eastern North American species should really not still be able to interbreed, much less still be the same species in many cases. As usual, creationism remains inadequate to explain the evidence satisfactorily. Evolution, however, can.

- Plants can interbreed comparatively successfully between species, and even between different families, far more so than animals.[208][209][210][211][212] The same is true of fungi.[213] Therefore, plants and fungi do not have to be as closely related to organisms they can reproduce with as animals. In light of this, it is rather revealing that the animals of the relevant areas are not mentioned in CMI's article.

Ray Comfort, in his book Origin of Species, a reprint of the original, notably omitted, among others, chapters 11 and 12, where Charles Darwin discussed the biogeographical evidence for evolution.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/science/Wallace-Line

- ↑ Thomas, Nicolas (June 2021). "From Sunda to Sahul: The first crossings and early settlement of the Pacific". Natural History.

- ↑ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2399087

- ↑ https://www.jstor.org/stable/2808563?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/cockatoo

- ↑ https://carolinabirds.org/HTML/Psitt_Cockatoo.htm

- ↑ https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/cassowary

- ↑ https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22678108/131902050

- ↑ https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22678114/118134784

- ↑ https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22678111/92755192

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Casuarius_unappendiculatus/

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/casuariiform

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Casuariidae/

- ↑ http://tolweb.org/Palaeognathae/15837

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Varanidae/

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1055790315003127?via%3Dihub

- ↑ https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature-and-arts/biographies/architecture-biographies/monitor-lizards

- ↑ https://theculturetrip.com/asia/thailand/articles/why-does-thailand-hate-monitor-lizards/

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/nov/11/lizard-traffickers-exploit-legal-loopholes-to-trade-at-worlds-biggest-fair

- ↑ http://www.catalogueoflife.org/col/details/species/id/a3df2212eee23842159af5497bfc0b1a/source/tree

- ↑ https://ebird.org/species/comqua1

- ↑ http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/common-quail-coturnix-coturnix

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Coturnix_japonica/

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Coturnix_pectoralis/

- ↑ https://ebird.org/species/broqua1

- ↑ http://birdlife.org.au/bird-profile/Brown-Quail

- ↑ https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22678955/92795779

- ↑ http://nzbirdsonline.org.nz/species/new-zealand-quail

- ↑ Megapodiidae - Scrub Fowl, Brush-turkeys

- ↑ Megapodiidae megapodes (Also: mound-builders or megapodes)

- ↑ Nicobar Scrubfowl Megapodius nicobariensis

- ↑ The distribution, status and conservation of the Nicobar megapode Megapodius nicobariensis

- ↑ https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/lydekkers-line

- ↑ https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/webers-line

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallacea

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/science/biogeographic-region/Fauna#ref588391

- ↑ https://www.livescience.com/37285-gondwana.html

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/place/Gondwana-supercontinent

- ↑ Gondwana- ancient supercontinent (from Britannica)

- ↑ Beringia- Ancient landform, Pacific Ocean, from Britannica

- ↑ https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/diapsids/birds/palaeognathae.html

- ↑ https://www.beautyofbirds.com/ratites.html

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/ratite

- ↑ https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/food-safety-education/get-answers/food-safety-fact-sheets/poultry-preparation/ratites-emu-ostrich-and-rhea/ct_index

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982216315032

- ↑ http://richleebruce.com/biology/emu.html

- ↑ https://phys.org/news/2017-03-evidence-ostriches-india-years.html

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1474-919X.1929.tb08775.x

- ↑ https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-45495400

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/26/science/largest-elephant-bird.html

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/elephant-bird#ref287389

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982216312143

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312306275_Phylogenomics_and_Morphology_of_Extinct_Paleognaths_Reveal_the_Origin_and_Evolution_of_the_Ratites

- ↑ https://biotaxa.org/Zootaxa/article/view/zootaxa.4032.5.2

- ↑ http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/6664

- ↑ http://fossilworks.org/?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=98813

- ↑ https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2018/02/09/262949.1.full.pdf

- ↑ http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/faculty/carr/araucari.htm

- ↑ http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/G/Araucariaceae/

- ↑ https://www.conifers.org/ar/Araucariaceae.php

- ↑ https://www.conifers.org/po/Podocarpaceae.php

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/plant/Podocarpaceae

- ↑ https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/seedplants/conifers/araucaria.html

- ↑ http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/G/Podocarpaceae/

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/plant/conifer/Annotated-classification#ref410967

- ↑ https://www.pacifichorticulture.org/articles/the-araucaria-family-past-present/

- ↑ R.A. Stockey Mesozoic Araucariaceae: Morphology and systematic relationships https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227151735_Mesozoic_Araucariaceae_Morphology_and_systematic_relationships

- ↑ Wagstaff, Steven Evolution and biogeography of the austral genus Phyllocladus (Podocarpaceae) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230184707_Evolution_and_biogeography_of_the_austral_genus_Phyllocladus_Podocarpaceae

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265079534_Dispersal_and_Paleoecology_of_Tropical_Podocarps

- ↑ Biogeography of Australasia: A Molecular Analysis by Michael Heads, page 201.https://books.google.com/books?id=IRiAAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA201&lpg=PA201&dq=podocarpaceae+range+%22japan%22+%22mexico%22&source=bl&ots=18MEHlt7BL&sig=ACfU3U2kfajwnvgBctYpfSBwg0PJmiWVgw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwips_nQ2pHiAhVDYKwKHXbrAsEQ6AEwCHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=podocarpaceae%20range%20%22japan%22%20%22mexico%22&f=false

- ↑ http://earthsci.org/expeditions/wollemi/wollemi.html

- ↑ Wollemia nobilis: A Living Fossil and Evolutionary Enigma

- ↑ https://www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/science/our-work-discoveries/germplasm-conservation-horticulture/wollemi-pine-conservation-program/wollemi-pine-research-projects/growth-of-wollemi-pine-in-cultivation

- ↑ https://www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/science/our-work-discoveries/germplasm-conservation-horticulture/wollemi-pine-conservation-program/wollemi-pine-research-projects/growth-of-wollemi-pine-in-cultivation

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23894439

- ↑ Conifers of the World: The Complete Reference by James E. Eckenwalder, page 631 https://books.google.com/books?id=QGmO_CtTPAEC&pg=PA631&lpg=PA631&dq=dilwynites+2+mya&source=bl&ots=xGsUVAMF4V&sig=ACfU3U3RNucXyjtkVf_n78sSBeSCPLqkuw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi825q3gJniAhUGoZ4KHdusCSsQ6AEwA3oECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ https://parasiticplants.siu.edu/parasitaxus.html

- ↑ http://legacy.brit.org/webfm_send/1767

- ↑ https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00606-002-0199-8

- ↑ https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0107679

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01378.x

- ↑ http://www.indefenseofplants.com/blog/2016/9/5/the-worlds-only-parasitic-gymnosperm

- ↑ Leaf evolution in Southern Hemisphere conifers tracks the angiosperm ecological radiation https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3223667/

- ↑ https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/vertebrates/sarco/dipnoi.html

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/lungfish

- ↑ Attenborough, David Life in Cold Blood, page 15

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/marsupial

- ↑ https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/marsupial

- ↑ https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/mammal/marsupial/marsupial.html

- ↑ https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=179917#null

- ↑ https://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Metatheria

- ↑ https://eol.org/pages/2844108

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4284630/

- ↑ https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/12/091215202320.htm

- ↑ https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Metatheria/

- ↑ https://ncse.com/creationism/analysis/marsupials

- ↑ https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/117/

- ↑ https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/microbiotheria-monitos-del-monte

- ↑ https://www.gbif.org/species/144097487

- ↑ https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/florida-vertebrate-fossils/species/didelphis-virginiana

- ↑ http://www.wildlifecontrolexperts.com/opossum.htm

- ↑ https://ifcnr.org/the-much-misunderstood-opossum/

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/plant/Fagales#ref992762

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263030041_Biogeography_evolution_and_palaeoecology_of_Nothofagus_Nothofagaceae_The_contribution_of_the_fossil_record

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1599775/

- ↑ https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2018.01073/full

- ↑ https://phys.org/news/2011-06-fossilized-pollen-reveals-climate-history.html

- ↑ https://academic.oup.com/botlinnean/article-pdf/174/4/503/25179467/boj12143.pdf

- ↑ http://tolweb.org/Parastacidae/6665

- ↑ https://academic.oup.com/jcb/article-pdf/31/2/320/10336292/jcb0320.pdf

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02374.x

- ↑ Phylogeny and biogeography of the freshwater crayfish Euastacus (Decapoda: Parastacidae) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA https://www.academia.edu/12214365/Phylogeny_and_biogeography_of_the_freshwater_crayfish_Euastacus_Decapoda_Parastacidae_based_on_nuclear_and_mitochondrial_DNA

- ↑ THE EVOLUTION OF QUEENSLAND SPINY MOUNTAIN CRAYFISH OF THE GENUS EUASTACUS. I. TESTING VICARIANCE AND DISPERSAL WITH INTERSPECIFIC MITOCHONDRIAL DNA https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00441.x

- ↑ Hansen, B Systematics and phylogeny of the Tasmanian freshwater crayfish genus Parastacoides (Decapoda: Parastacidae) https://eprints.utas.edu.au/19930/

- ↑ Burnham, Quinton Systematics and biogeography of the Australian burrowing freshwater crayfish genus Engaewa Riekk (Decapoda: Parastacidae) https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1278/

- ↑ http://jur.byu.edu/?p=9721

- ↑ Lavoue, Sebastien. Was Gondwanan breakup the cause of the intercontinental distribution of Osteoglossiformes? A time-calibrated phylogenetic test combining molecular, morphological, and paleontological evidencehttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/298338093_Was_Gondwanan_breakup_the_cause_of_the_intercontinental_distribution_of_Osteoglossiformes_A_time-calibrated_phylogenetic_test_combining_molecular_morphological_and_paleontological_evidence

- ↑ From Chromosomes to Genome: Insights into the Evolutionary Relationships and Biogeography of Old World Knifefishes (Notopteridae; Osteoglossiformes) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6027293/

- ↑ Cytogenetics, genomics and biodiversity of the South American and African Arapaimidae fish family (Teleostei, Osteoglossiformes) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6433368/

- ↑ OSTEOGLOSSIDAE:Bony Tongues https://bie.ala.org.au/species/urn:lsid:biodiversity.org.au:afd.taxon:1102b16d-864b-422a-8008-d2bc801049bd#cite_note-7

- ↑ Molecular Phylogeny of Osteoglossoids: A New Model for Gondwanian Origin and Plate Tectonic Transportation of the Asian Arowana https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/17/12/1869/1059640

- ↑ Yoshinori Kumazawa The reason the freshwater fish arowana live across the sea https://web.archive.org/web/20120205000120/http://www.brh.co.jp/en/experience/journal/39/research_1.html

- ↑ http://www.onlythebestfossils.com/green-river-formation6.html

- ↑ http://www.csun.edu/~msteele/classes/Ich530/lectures/5_teleosts%20I.pdf

- ↑ http://oaji.net/articles/2014/652-1396784299.pdf

- ↑ Fish- Annotated Classification

- ↑ http://tolweb.org/Osteoglossomorpha

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/osteoglossomorph#ref525684

- ↑ http://www.wetwebmedia.com/FWSubWebIndex/osteoglossiforms.htm

- ↑ Family Osteoglossidae - Arowanas from FishBase

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15037637

- ↑ Giant fish of Amazon faces extinction

- ↑ Volker Blum Vertebrate Reproduction: A Textbook Page 93 https://books.google.com/books?id=JZfzCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA93&lpg=PA93&dq=mormyridae++gymnarchidae+no+flagellum&source=bl&ots=_7czk9B4HX&sig=ACfU3U1EXdjPNyvyBpHiud04D9YWA38brg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwik3JTStYDjAhVJeawKHXwvDLwQ6AEwDHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=mormyridae%20%20gymnarchidae%20no%20flagellum&f=false

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/animal/osteoglossomorph

- ↑ Mooneyes (Family Hiodontidae)

- ↑ Hiodontidae on FishBase https://www.fishbase.se/summary/FamilySummary.php?ID=36

- ↑ Family Galaxiidae - Galaxiids

- ↑ D. E. Lee,R. M. McDowall &J. K. Lindqvist, Galaxias fossils from Miocene lake deposits, Otago, New Zealand: The earliest records of the Southern Hemisphere family Galaxiidae (Teleostei)

- ↑ Proteales-Brittanica

- ↑ The Evolution of Proteaceae

- ↑ Molecular dating of the ‘Gondwanan’ plant family Proteaceae is only partially congruent with the timing of the break‐up of Gondwana

- ↑ Prance, G.T. (2009). Neotropical Proteaceae. In: Milliken, W., Klitgård, B. & Baracat, A. (2009 onwards), Neotropikey - Interactive key and information resources for flowering plants of the Neotropics. http://www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/neotropikey/families/Proteaceae.htm

- ↑ Molecular dating of the ‘Gondwanan’ plant family Proteaceae is only partially congruent with the timing of the break‐up of Gondwana. https://www.academia.edu/3543049/Molecular_dating_of_the_Gondwanan_plant_family_Proteaceae_is_only_partially_congruent_with_the_timing_of_the_break-up_of_Gondwana

- ↑ Pre-Gondwanan-breakup origin of Beauprea (Proteaceae) explains its historical presence in New Caledonia and New Zealand https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/2/4/e1501648.full

- ↑ Levin's work

- ↑ The relevant discussion.

- ↑ "Acipenseriformes - Paddlefish, Sturgeons" on NHPBS

- ↑ Redescription of †Chondrosteus acipenseroides Egerton, 1858 (Acipenseriformes, †Chondrosteidae) from the lower Lias of Lyme Regis (Dorset, England), with comments on the early evolution of sturgeons and paddlefishes Eric J. Hilton &Peter L. Forey

- ↑ Chondrosteidae on Wikimedia Commons, for comparison.

- ↑ Sturgeon- New World Encyclopedia

- ↑ Paddlefish- New World Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Chinese Paddlefish Psephurus gladius" - National Geographic

- ↑ Peter C. Revkin, "For Chinese Paddlefish, Another Long Goodbye" from the New York Times

- ↑ 14 animals declared extinct in the 21st century

- ↑ Specimen: UMMP VP 22206

- ↑ Lance Grande &William E. Bemis, "Osteology and Phylogenetic Relationships of Fossil and Recent Paddlefishes (Polyodontidae) with Comments on the Interrelationships of Acipenseriformes"

- ↑ ,Lance Grande, The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time, page 111

- ↑ "Eocene Biodiversity: Unusual Occurrences and Rarely Sampled Habitats-edited by Gregg F. Gunnell", page 11

- ↑ The Magnolia Family (Magnoliaceae): A Primitive Family Of Flowering Plants

- ↑ Magnolia (Plant) -Britannica

- ↑ Magnoliales:Distribution -Britannica

- ↑ "The Plants of China" edited by De-Yuan Hongand Stephen Blackmore, page 93. https://books.google.com/books?id=aCw7CQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Hiroshi Azuma, José G. García-Franco, Victor Rico-Gray and Leonard B. Thien, "Molecular Phylogeny of the Magnoliaceae: The Biogeography of Tropical and Temperate Disjunctions" from the American Journal of Botany

- ↑ C. Barry Cox, Peter D. Moore Biogeography: An Ecological and Evolutionary Approach, page 50. https://books.google.com/books?id=GP5HeCwkV2IC&pg=PA50&lpg=PA50#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ "Botany Blueprint: The Southern Magnolia" by Anna Laurent from Print Magazine

- ↑ Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) Plant Guide -USDA

- ↑ Susan French, Roger Huff "Evaluating Trees for Saltwater Spray Tolerance for Oceanfront Sites"

- ↑ "Trees and Shrubs that Tolerate Saline Soils and Salt Spray Drift"

- ↑ Leonard B. Thien, "Floral Biology of Magnolia"

- ↑ The Beguiling History of Bees [Excerpt] by Dave Goulson from Scientific American

- ↑ S. C. Willemsten, "An Evolutionary Basis for Pollination Ecology", page 271. https://books.google.com/books?id=5-sUAAAAIAAJ

- ↑ Manju V. Sharma, Joseph E. Armstrong, "Pollination of Myristica and Other Nutmegs in Natural Populations"

- ↑ Joseph E. Armstrong and Anthony K. Irvine, "Floral Biology of Myristica insipida (Myristicaceae), a Distinctive Beetle Pollination Syndrome"

- ↑ Leonard B. Thien, "Patterns of Pollination in the Primitive Angiosperms"

- ↑ Joseph E. Armstrong and Anthony K. Irvine, "Functions of Staminodia in the Beetle-Pollinated Flowers of Eupomatia laurina"

- ↑ Gerhard Gottsberger, Ilse Silberbauer-Gottsberger, "Basal angiosperms and beetle pollination"

- ↑ L. van der Pijl, "Ecological Aspects of Flower Evolution. I. Phyletic Evolution"Note paper is from 1960, possibly outdated.

- ↑ Gerhard Gottsberger, "How diverse are Annonaceae with regard to pollination?"

- ↑ Gerhard Gottsberger, Ilse Silberbauer-Gottsberger, Roger S. Seymour, Stefan Dötterl, "Pollination ecology of Magnolia ovatamay explain the overall large flower size of the genus".

- ↑ Joseph E.Armstrong, "Pollination by deceit in nutmeg (Myristica insipida, Myristicaceae): floral displays and beetle activity at male and female trees."https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2307/2446051

- ↑ http://faculty.washington.edu/gpwilson/Paleobiogeography.htm

- ↑ https://eeb.ku.edu/sites/eeb.ku.edu/files/files/bsl/annurevecolsys.pdf

- ↑ http://www-personal.umich.edu/~wilsonja/Titanosauria/Paleobiogeography.html

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2468517817300060

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080454054006017

- ↑ https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128143506000021

- ↑ https://www.jstor.org/stable/216087?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4920332/

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4810818/

- ↑ http://publish.illinois.edu/alfredwegener/evidence/

- ↑ https://www.upi.com/Science_News/2018/09/10/Cave-features-suggest-stable-sea-levels-during-last-interglacial-period/1341536601363/

- ↑ http://facstaff.uwa.edu/jmccall/Biogeog/Great%20American%20Interchange.ppt

- ↑ Michael O. Woodburne, "The Great American Biotic Interchange: Dispersals, Tectonics, Climate, Sea Level and Holding Pens"

- ↑ Notoungulta- fossil mammals (Britannica)

- ↑ The reign of the terror birds

- ↑ S. David Webb, "Mammalian Faunal Dynamics of the Great American Interchange"

- ↑ Quaternary glaciation and the Great American Biotic Interchange

- ↑ "Ecogeography and the Great American Interchange" by S. David Webb

- ↑ Alfred Russell Wallace, "The Geographical Distribution of Animals" pages 81-82

- ↑ Allopatric speciation- PBS

- ↑ An example of allopatric speciation- Biology Forums

- ↑ https://creation.com/biogeography-against-evolution

- ↑ https://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/0_0_0/genovspheno_01

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4439200/

- ↑ http://www.ped.fas.harvard.edu/files/ped/files/genetics06_0.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5161288/

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/evo.12302

- ↑ http://www.biologyreference.com/Ho-La/Hybridization-Plant.html

- ↑ https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rstb.2008.0055

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4031106/

- ↑ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09670260010001735721

- ↑ https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02886345

- ↑ The Role of Hybridization in the Evolution and Emergence of New Fungal Plant Pathogens. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26824768

KSF

KSF