Accountable care organization

From Ballotpedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Ballotpedia - Reading time: 8 min

This article does not receive scheduled updates. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia. Contact our team to suggest an update.

| Healthcare policy in the U.S. |

|---|

| Obamacare overview |

| Obamacare lawsuits |

| Medicare and Medicaid |

| Healthcare statistics |

An accountable care organization (ACO) is a group of doctors, hospitals, or other healthcare providers that work together with the purpose of delivering high-quality care at a lower cost. The idea is to shift some financial risk for outcomes away from payers and onto providers by giving ACOs a portion of any savings they realize for payers, but also requiring them to shoulder any losses. Although the framework for these organizations was established by the Affordable Care Act as a new model for Medicare reimbursement, ACOs have been adopted in the private sector as well.

Overview[edit]

An accountable care organization (ACO) is a group of doctors, hospitals, or other healthcare providers that work together and take on some risk of financial losses, with the purpose of delivering high-quality care at a lower cost. Accountable care organizations (ACOs) were established on a trial basis by the Affordable Care Act as a new healthcare delivery model for Medicare providers.[1][2]

The idea is to shift some financial risk for health outcomes away from payers and onto providers. If an ACO spends less money treating Medicare patients than it did previously, then the ACO receives a bonus on its reimbursement. If not, the group will have to take a loss on the cost of care provided to those patients. Bonuses are higher for ACOs that also demonstrate improved quality, but ACOs that do not meet quality metrics do not receive any bonus, even if they generated savings for Medicare. Bonuses and losses are shared equally by all members of the group.[1][2]

Participation in an ACO is voluntary; ACOs can be formed by physicians, hospitals, or—in the private market—insurers. However, if a provider chooses to join or create a Medicare ACO, there are requirements. For instance, an ACO must serve a minimum of 5,000 Medicare beneficiaries for at least three years. The law also contains a number of less specific requirements, including the adoption of health information technology, such as electronic health records. A series of case studies released in 2011 by the American Hospital Association stated that the costs of establishing an ACO can reach up to about $26 million because of these and other requirements. These costs were reportedly not included in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services' original estimate of about $1.8 million in start-up costs.[3]

Growth[edit]

Although the accountable care organization (ACO) provision of the Affordable Care Act pertains specifically to Medicare, some providers have formed ACOs for patients with private insurance, and 16 state Medicaid programs contracted with ACOs as of 2015 as well. According to the journal Health Affairs, as of September 2015, the majority of the 23.5 million individuals served by ACOs were enrolled in private insurance or Medicaid. Medicare patients accounted for 7.8 million of the individuals in ACOs.[4]

According to Leavitt Partners, a healthcare research group, the number of ACOs in the United States rose steadily between 2010 and 2016. From 2010 to January 2016, 838 ACOs were created, with about 94 created in 2015.[5]

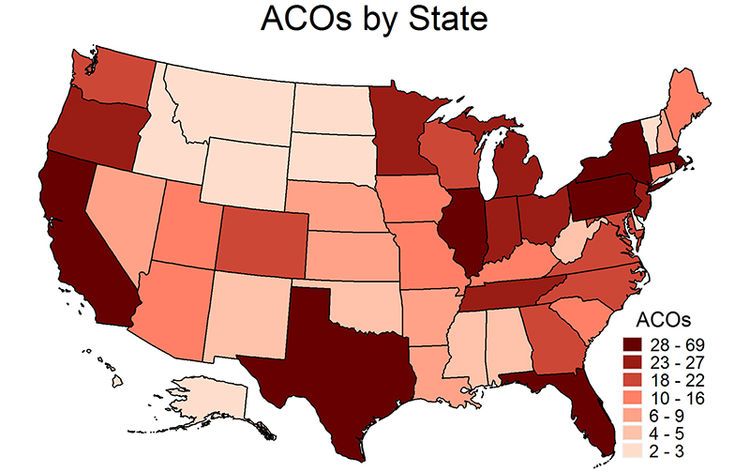

The number of ACOs in each state varies by state, although each state had at least two as of January 2016. Several of the most populous states, including California, Florida, Illinois, New York, and Texas, also had the greatest numbers of ACOs. Low-population states such as Alaska, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont had fewer ACOs. The map below shows the number of ACOs in each state. Click [show] on the red bar below the map to view a table with the ranges by state.[5]

| Number of accountable care organizations by state, 2016 | |

|---|---|

| State | Number of ACOs |

| Alabama | 4-5 |

| Alaska | 2-3 |

| Arizona | 10-16 |

| Arkansas | 6-9 |

| California | 28-69 |

| Colorado | 18-22 |

| Connecticut | 10-16 |

| Delaware | 2-3 |

| Florida | 28-69 |

| Georgia | 18-22 |

| Hawaii | 2-3 |

| Idaho | 2-3 |

| Illinois | 28-69 |

| Indiana | 23-27 |

| Iowa | 10-16 |

| Kansas | 6-9 |

| Kentucky | 10-16 |

| Louisiana | 6-9 |

| Maine | 10-16 |

| Maryland | 18-22 |

| Massachusetts | 28-69 |

| Michigan | 23-27 |

| Minnesota | 23-27 |

| Mississippi | 4-5 |

| Missouri | 10-67 |

| Montana | 2-3 |

| Nebraska | 6-9 |

| Nevada | 6-9 |

| New Hampshire | 6-9 |

| New Jersey | 23-27 |

| New Mexico | 4-5 |

| New York | 28-69 |

| North Carolina | 18-22 |

| North Dakota | 2-3 |

| Ohio | 23-27 |

| Oklahoma | 4-5 |

| Oregon | 23-27 |

| Pennsylvania | 28-69 |

| Rhode Island | 6-9 |

| South Carolina | 10-16 |

| South Dakota | 2-3 |

| Tennessee | 23-27 |

| Texas | 28-69 |

| Utah | 10-16 |

| Vermont | 2-3 |

| Virginia | 18-22 |

| Washington | 18-22 |

| West Virginia | 4-5 |

| Wisconsin | 18-22 |

| Wyoming | 2-3 |

| United States | 838 |

| Source: Health Affairs Blog | |

Support and opposition[edit]

Support[edit]

Proponents of accountable care organizations (ACOs) say that they will improve the quality of care for patients, mainly through better care coordination between providers. According to EHR Intelligence, an organization that publishes news related to health information technology, one of the pros of ACOs is that having providers involved share the risk of financial gains and losses "promotes health information exchange (HIE) that allows providers to communicate effectively and efficiently with other organizations, helping in the coordination of care for patients." EHR Intelligence also says better care coordination will cut down on duplicate and unnecessary tests and procedures and improve the accuracy of diagnoses.[6]

The American Academy of Family Physicians, a medical organization representing primary care physicians, argues that joining an ACO can help providers adopt up-to-date health information technology and handle new data collection and reporting requirements issued by commercial insurers and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. EHR Intelligence argues that when new processes and infrastructure are adopted by an ACO rather than a lone physician, the costs of these investments are spread among all members, who will also all reap the benefits, including data aggregation and population health control. This type of investment is more difficult for single physicians that do not group together with others, according to the publication.[6][7]

Opposition[edit]

Kip Sullivan, a board member of the Minnesota chapter of Physicians for a National Health Program, argues that the accountable care organization (ACO) model was relatively untested before implementation and that there is little empirical evidence of their efficacy in achieving cost savings and quality improvements. Sullivan further argues that meaningful research is almost impossible because ACOs have been given a vague, untestable definition based on what policymakers hope ACOs will do. Sullivan also says that the research that does exist shows that ACO cost savings are too small to make any difference or that ACOs in some cases have increased costs.[8][9]

The Heritage Foundation argues that the formation of ACOs will drive greater consolidation within the healthcare industry. The foundation outlined how the ACO model might result in provider consolidation:[10]

| “ | Groups of independent practitioners as well as other types of small and mid-sized practices may lack the infrastructure, Internet technology, or other resources needed to qualify and succeed on their own. Also, smaller, entrepreneurial organizations that want to venture alone may find themselves competing against similar physicians’ practices that have joined ACOs or been acquired by larger organizations.[11] | ” |

| —Heritage Foundation[10] | ||

Health Affairs, a health policy journal, published an issue brief that stated such consolidation could lead to higher healthcare costs as health systems gain a greater market share and have more leverage to negotiate higher prices with insurers.[12]

Studies[edit]

In a review of one of the Medicare ACO programs that included 32 ACOs, the Health Affairs Blog found that 12 shared in savings, 19 shared neither savings nor losses, and one shared in losses. Its review of the first year of a separate program—the Medicare Shared Savings Program—found that of 114 ACOs, 29 spent under budget and shared in savings, 25 spent under budget but not enough to share in savings, 58 spent over budget but not enough to share in losses, and two spent over budget and shared in losses. Additionally, according to an analysis of the Medicare data performed by Health Affairs, there was no correlation between improved quality and savings. This means that ACOs that generated savings did not always improve the quality of care provided, and vice versa.[13][14][15]

Recent news[edit]

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms Accountable care organization. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- Leavitt Partners

- Kaiser Health News, "Accountable Care Organizations, Explained"

- Health Affairs, "Health Policy Brief: Next Steps for ACOs"

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Politico, "Understanding Obamacare: POLITICO's Guide to the Affordable Care Act," accessed October 21, 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Health Affairs, "Health Policy Brief: Next Steps for ACOs," January 13, 2012

- ↑ American Hospital Association, "New study finds the start-up costs of establishing an ACO to be significant," accessed November 23, 2015

- ↑ Health Affairs Blog, "ACO Results: What We Know So Far," May 30, 2014

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Muhlestein, David, Health Affairs Blog, "Accountable Care Organizations In 2016: Private And Public-Sector Growth And Dispersion," April 21, 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 EHR Intelligence, "Pros and cons of accountable care: Is an ACO right for you?" June 12, 2013

- ↑ American Academy of Family Physicians, "Accountable Care Organizations," accessed April 26, 2016

- ↑ The Health Care Blog, "Why We Have so Little Useful Research on ACOs," February 16, 2016

- ↑ The Health Care Blog, "How Not to Research ACOs," February 22, 2016

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 The Heritage Foundation, "Why Accountable Care Organizations Won’t Deliver Better Health Care—and Market Innovation Will," April 18, 2011

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Health Affairs, "Health Policy Brief: Next Steps for ACOs," January 31, 2016

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedkhnaco - ↑ Health Affairs Blog, "ACO Results: What We Know So Far," May 30, 2014

- ↑ Health Affairs, "ACO Quality Results: Good But Not Great," December 18, 2014

KSF

KSF