Public education in New York

From Ballotpedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Ballotpedia - Reading time: 17 min

| K-12 education in New York | |

| |

| Education facts | |

| State superintendent: Betty A. Rosa | |

| Number of students: 2,488,476 | |

| Number of teachers: 205,293 | |

| Teacher/pupil ratio: 1:12 | |

| Number of school districts: 686 | |

| Number of schools: 4,360 | |

| Graduation rate: 83% | |

| Per-pupil spending: $25,519 | |

| See also | |

| New York Department of Education • List of school districts in New York • New York • School boards portal | |

Public education in the United States Public education in New York Glossary of education terms | |

| Note: The statistics on this page are mainly from government sources, including the U.S. Census Bureau and the National Center for Education Statistics. Figures given were the most recent as of June 2015. | |

The New York public school system (prekindergarten through grade 12) operates within districts governed by locally elected school boards and superintendents. In 2022, New York had 2,488,476 students enrolled in a total of 4,360 schools in 686 school districts. There were 205,293 teachers in the public schools, or roughly one teacher for every 12 students, compared to the national average of 1:16. In 2020, New York spent on average $25,519 per pupil.[1] The state's graduation rate was 83 percent in the 2018-2019 school year.[2]

General information[edit]

- See also: General comparison table for education statistics in the 50 states and Education spending per pupil in all 50 states

The following chart shows how New York compares to the national level for the most recent years for which data is available.

| Public education in New York | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Schools | Districts | Students | Teachers | Teacher to pupil ratio | Per pupil spending* | |

| New York | 4,360 | 686 | 2,488,476 | 205,293 | 1:12 | $25,519 | |

| United States | 90,323 | 13,194 | 47,755,383 | 2,783,705 | 1:16 | $13,494 | |

| *Per pupil spending data reflects information reported for fiscal year 2020. Sources: Education statistics in the United States | |||||||

Academic performance[edit]

![]() The sections below do not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

The sections below do not contain the most recently published data on this subject. If you would like to help our coverage grow, consider donating to Ballotpedia.

| Education terms |

|---|

| |

| For more information on education policy terms, see this article. |

NAEP scores[edit]

- See also: NAEP scores by state

The National Center for Education Statistics provides state-by-state data on student achievement levels in mathematics and reading in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The table below presents the percentage of fourth and eighth grade students that scored at or above proficient in reading and math during school year 2012-2013. Compared to three neighboring states (Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania), New York had the lowest percentage of students score at or above proficient in every category.[3]

| Percent of students scoring at or above proficient, 2012-2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Math - Grade 4 | Math - Grade 8 | Reading - Grade 4 | Reading - Grade 8 | |

| New York | 40% | 32% | 37% | 35% |

| Massachusetts | 58% | 55% | 47% | 48% |

| New Jersey | 49% | 49% | 42% | 46% |

| Pennsylvania | 44% | 42% | 40% | 42% |

| United States | 41% | 34% | 34% | 34% |

| Source: United States Department of Education, ED Data Express, "State Tables" | ||||

Graduation, ACT and SAT scores[edit]

The following table shows the graduation rates and average composite ACT and SAT scores for New York and surrounding states during the 2012-2013 school year. All statements made in this section refer to that school year.[3][4][5]

In the United States, public schools reported graduation rates that averaged to about 81.4 percent. About 54 percent of all students in the country took the ACT, while 50 percent reported taking the SAT. The average national composite scores for those tests were 20.9 out of a possible 36 for the ACT, and 1498 out of a possible 2400 for the SAT.[6]

New York schools reported a graduation rate of 76.8 percent during the 2012-2013 school year, lowest among its neighboring states.

In New York, more students took the SAT than the ACT in 2013, earning an average SAT score of 1463.

| Comparison table for graduation rates and test scores, 2012-2013 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Graduation rate, 2013 | Average ACT composite, 2013 | Average SAT composite, 2013 | ||||

| Percent | Quintile ranking** | Score | Participation rate | Score | Participation rate | ||

| New York | 76.8% | Fourth | 23.4 | 26% | 1463 | 76% | |

| Massachusetts | 85% | Second | 24.1 | 22% | 1553 | 83% | |

| New Jersey | 87.5% | First | 23 | 23% | 1521 | 78% | |

| Pennsylvania | 85.5% | Second | 22.7 | 18% | 1480 | 71% | |

| United States | 81.4% | 20.9 | 54% | 1498 | 50% | ||

| **Graduation rates for states in the first quintile ranked in the top 20 percent nationally. Similarly, graduation rates for states in the fifth quintile ranked in the bottom 20 percent nationally. Sources: United States Department of Education, "ED Data Express" ACT.org, "2013 ACT National and State Scores" The Commonwealth Foundation, "SAT scores by state, 2013" | |||||||

Dropout rate[edit]

- See also: Public high school dropout rates by state for a full comparison of dropout rates by group in all states

The high school event dropout rate indicates the proportion of students who were enrolled at some time during the school year and were expected to be enrolled in grades nine through 12 in the following school year but were not enrolled by October 1 of the following school year. Students who have graduated, transferred to another school, died, moved to another country, or who are out of school due to illness are not considered dropouts. The average public high school event dropout rate for the United States remained constant at 3.3 percent for both school year 2010–2011 and school year 2011–2012. The event dropout rate for New York was higher than the national average at 3.6 percent in the 2010-2011 school year, and 3.8 percent in the 2011-2012 school year.[7]

Educational choice options[edit]

- See also: School choice in New York

New York had the sixth highest private school attendance rate in the United States as of 2014. Other school choice options in the state included charter schools, homeschooling, online learning and voluntary inter-district public school open enrollment as of June 2015.

Developments[edit]

Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020)[edit]

On June 30, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court decided Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, which concerned whether the government can exclude religious institutions from student-aid programs. The case related to Article X, Section 6 of the Montana Constitution, also known as Montana’s Blaine Amendment.[8]

In its 5-4 opinion, the court held that the application of Article X, Section 6 violated the free exercise clause of the U.S. Constitution. The majority held Article X, Section 6 barred religious schools and parents who wished to send their children to those schools from receiving public benefits because of the religious character of the school.[9]

The case addressed the tension between the free exercise and Establishment clauses of the U.S. Constitution—where one guarantees the right of individuals' free exercise of religion and the other guarantees that the state won't establish a religion—and the intersections of state constitutions with state law and with the U.S. Constitution.

New York is one of the states with a Blaine Amendment.

Education funding and expenditures[edit]

- See also: New York state budget and finances

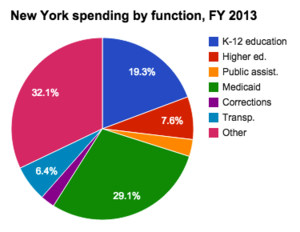

Source: National Association of State Budget Officers

According to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO), states spent an average of 19.8 percent of their total budgets on elementary and secondary education during fiscal year 2013. In addition, the United States Census Bureau found that approximately 45.6 percent of the country's school system revenue came from state sources, while about 45.3 percent came from local sources. Local revenue is generated primarily by property taxes. The remaining portion of school system revenue came from federal sources.[10][11]

New York spent approximately 19.3 percent of its budget on elementary and secondary education during fiscal year 2013. School system revenue came primarily from local funds. New York spent the second highest on public education as a percentage of its total budget when compared to its neighboring states.

| Comparison of financial figures for school systems, fiscal year 2013 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Percentage of budget | Per pupil spending | Revenue sources | ||||

| Percent federal funds | Percent state funds | Percent local funds | |||||

| New York | 19.3% | $19,818 | 5.6% | 39.8% | 54.6% | ||

| Massachusetts | 11.2% | $14,515 | 5.1% | 40.2% | 54.7% | ||

| New Jersey | 24.9% | $17,572 | 4.1% | 38.7% | 57.2% | ||

| Pennsylvania | 14.9% | $13,864 | 7.6% | 36.1% | 56.3% | ||

| United States | 19.8% | $10,700 | 9.1% | 45.6% | 45.3% | ||

| Sources: NASBO, "State Expenditure Report" (Table 8). U.S. Census Bureau, "Public Education Finances: 2013, Economic Reimbursable Surveys Division Reports" (Table 5 and Table 8). | |||||||

Revenue breakdowns[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, public school system revenues totaled approximately $598 billion in fiscal year 2013.[11]

In New York, the primary source of school system revenue was local funding during fiscal year 2013, at $32.4 billion. New York reported significantly higher total public education revenue than any of its neighboring states.

| Revenues by source, fiscal year 2013 (amounts in thousands) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Federal revenue | State revenue | Local revenue | Total revenue |

| New York | $3,335,657 | $23,632,698 | $32,430,464 | $59,398,819 |

| Massachusetts | $818,054 | $6,428,534 | $8,732,961 | $15,979,549 |

| New Jersey | $1,120,771 | $10,458,175 | $15,449,220 | $27,028,166 |

| Pennsylvania | $2,049,113 | $9,764,558 | $15,210,613 | $27,024,284 |

| United States | $54,367,305 | $272,916,892 | $270,645,402 | $597,929,599 |

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau, "Public Education Finances: 2013, Economic Reimbursable Surveys Division Reports" (Table 1) | ||||

Expenditure breakdowns[edit]

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, public school system expenditures totaled approximately $602 billion in fiscal year 2012. [12]

Public education expenditures in New York totaled approximately $58.1 billion in fiscal year 2012. New York reported significantly higher total public education expenditures than any of its neighboring states.

| Expenditures by type, fiscal year 2012 (amounts in thousands) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | General expenditures | Capital outlay | Other | Total expenditures |

| New York | $52,460,494 | $2,097,414 | $3,538,973 | $58,096,880 |

| Massachusetts | $14,151,659 | $1,117,723 | $302,920 | $15,572,302 |

| New Jersey | $24,391,278 | $912,022 | $828,162 | $26,131,462 |

| Pennsylvania | $23,190,198 | $1,822,157 | $1,584,480 | $26,596,835 |

| United States | $527,096,473 | $48,773,386 | $25,897,123 | $601,766,981 |

| Source: National Center for Education Statistics, "Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education: School Year 2011–12 (Fiscal Year 2012)" (Table 5) | ||||

Personnel salaries[edit]

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average national salary for classroom teachers in public elementary and secondary schools declined by 1.3 percent from the 1999-2000 school year to the 2012-2013 school year. During the same period in New York, the average salary increased by 8 percent.[14]

| Estimated average salaries for teachers (in constant dollars**) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999-2000 | 2009-2010 | 2011-2012 | 2012-2013 | Percent difference | |

| New York | $69,723 | $76,464 | $74,620 | $75,279 | 8.0% |

| Massachusetts | $63,656 | $73,945 | $72,915 | $73,129 | 14.9% |

| New Jersey | $71,083 | $69,523 | $68,194 | $68,797 | -3.2% |

| Pennsylvania | $66,035 | $63,146 | $62,965 | $63,521 | -3.8% |

| United States | $57,133 | $58,925 | $56,340 | $56,383 | -1.3% |

| **"Constant dollars based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI), prepared by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, adjusted to a school-year basis. The CPI does not account for differences in inflation rates from state to state." | |||||

Organizations[edit]

State agencies[edit]

- See also: New York State Education Department

The New York State Education Department is led by the New York Commissioner of Education. MaryEllen Elia was appointed to the position in 2015. The State Education Department has eight main offices: the Office of P-12 Education, the Office of Higher Education, the Office of Cultural Education, the Office of Performance Improvement and Management Services, the Chief Financial Office, the Office of Counsel, the Office of the Professions, and the Office of Adult Career and Continuing Educational Services.[15]

The mission statement of the New York State Education Department reads:[15]

| “ | Our mission is to raise the knowledge, skill, and opportunity of all the people in New York. Our vision is to provide leadership for a system that yields the best educated people in the world.[16] | ” |

Unions[edit]

In 2012, the Fordham Institute and Education Reform Now assessed the power and influence of state teacher unions in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Their rankings were based on 37 different variables in five broad areas: resources and membership, involvement in politics, scope of bargaining, state policies and perceived influence. New York ranked ninth overall for union power and influence, or "strongest," which was in the first tier of five.[17]

The primary union within the New York school system is the New York State United Teachers (NYSUT), an affiliate of the National Education Association (NEA).

List of local New York school unions:[18]

- American Federation of Teachers (New York City)

- New York State United Teachers

- New York State United Teachers (Latham)

- National Education Association Of New York

- Buffalo Teachers Federation

- Yonkers Federation Of Teachers

- American Federation of Teachers (Rochester)

- American Federation of Teachers (Niagra Falls)

- Catholic Lay Teachers Group Of The Archdiocese Of New York

- American Federation of Teachers (Ronkonkoma)

Government sector lobbying[edit]

- See also: New York government sector lobbying

The main education government sector lobbying organization is the New York State School Boards Association.

Transparency[edit]

The state of New York has two transparency resources that monitor government spending: Open Book New York, created by State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, and Project Sunlight, created by Governor Andrew Cuomo.

Studies and reports[edit]

Quality Counts 2014[edit]

- See also: Education Week survey

Education Week, a publication that reports on many education issues throughout the country, began using an evaluation system in 1997 to grade each state on various elements of education performance. This system, called Quality Counts, uses official data on performance from each state to generate report cards for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The report card in 2014 uses six different categories:

- Chance for success

- K-12 achievement

- Standards, assessments and accountability

- The teaching profession

- School finance

- Transitions and alignment

Each of these six categories had a number of other elements that received individual scores. Those scores were then averaged and used to determine the final score in each category. Every state received two types of scores for each of the six major categories: A numerical score out of 100 and a letter grade based on that score. Education Week used the score for the first category, "chance for success," as the value for ranking each state and the District of Columbia. The average grade received in the entire country was 77.3, or a C+ average. The country's highest average score was in the category of "standards, assessments and accountability" at 85.3, or a B average. The lowest average score was in "K-12 achievement", at 70.2, or a C- average.

New York received a score of 81, or a B- average in the "chance for success" category. This was above the national average. The state's highest score was in "standards, assessments and accountability" at 92, or an A- average. The lowest score was in "K-12 achievement" at 70.2, or a C- average. New York had the third highest score in the "school finance" category in the country. The chart below displays the scores of New York and its surrounding states. A full discussion of how these numbers were generated can be found here.[19]

Note: Click on a column heading to sort the data.

| Public education report cards, 2014 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Chance for success | K-12 achievement | Standards, assessments and accountability | The teaching profession | School finance | Transitions and alignment |

| New York | 81.0 (B-) | 70.2 (C-) | 92.0 (A-) | 81.5 (B-) | 87.2 (B+) | 85.7 (B) |

| Massachusetts | 91.4 (A-) | 83.7 (B) | 88.4 (B+) | 78.7 (C+) | 83.5 (B) | 75.0 (C) |

| New Jersey | 88.2 (B+) | 82.1 (B-) | 75.5 (C) | 67.2 (D+) | 84.5 (B) | 82.1 (B-) |

| Pennsylvania | 82.6 (B) | 75.6 (C) | 77.7 (C+) | 74.6 (C) | 82.0 (B-) | 78.6 (C+) |

| United States | 77.3 (C+) | 70.2 (C-) | 85.3 (B) | 72.5 (C) | 75.5 (C) | 81.1 (B-) |

| Source: Education Week, "Quality Counts 2014" | ||||||

State Budget Solutions education study[edit]

State Budget Solutions examined national trends in education from 2009 to 2011, including state-by-state analysis of education spending, graduation rates and average ACT scores. The study showed that the states that spent the most did not have the highest average ACT test scores, nor did they have the highest average graduation rates. A summary of the study is available here. The full report can be accessed here.

Issues[edit]

New York City preschool expansion[edit]

One of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio's (D) primary campaign planks in 2013 was the establishment of free, full-day prekindergarten to help low-income families who live in the city's school district. His initial proposal financed the expansion by raising taxes on high-income city residents.[20] On March 29, 2014, Governor Andrew Cuomo and leaders in the New York State Legislature reached an agreement on the state budget. The budget included $300 million in funding for the New York City prekindergarten expansion, but it did not use Mayor de Blasio's tax plan to finance the expenditures. The funding was also less than the $340 million requested by the city, and the budget included a requirement for the New York City government to allocate space in public school buildings or to pay a share of the overhead expenses for charter schools on private land in the city, which Mayor de Blasio had previously fought. He still celebrated the announcement, arguing that it was "an extraordinary and historic step forward for New York City. [...] It’s clearly the resources we need to create full-day pre-K for every child in this city. That’s what we set out to do."[21]

The city intended to enroll approximately 53,000 full-day preschool children during the 2014-2015 school year. Before the expansion, the city had facilities for approximately 20,000 full-day preschool students. Center for Children's Initiatives Executive Director Nancy Kolben, who served on the committee formed by Mayor de Blasio to handle the prekindergarten plan, stated that the goal was to have 70,000 full-day children enrolled for the 2015-2016 school year.[22] Mayor de Blasio charged Sophia Pappas, executive director of the city's Office of Early Childhood Education, with the implementation of the program.[23]

Mandated mental health instruction in schools[edit]

In 2016, Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed legislation requiring schools to include mental health instruction in the basic K-12 curriculum. The law required the New York Board of Education to establish guidelines for the curriculum. Local school districts were charged with developing curriculum and lesson plans. The purpose of the law, according to its sponsors, was to assist students in recognizing the signs of mental illness and to seek help when needed. John Richter, director of public policy at the Mental Health Association in New York, said, "The intent of this law is to take a public health approach to teaching about mental health. In other words, giving students the knowledge and resources they need to help recognize the early signs of mental health problems and how to get help." The law took effect in July 2018. New York was the first state to enact a law requiring mental health instruction in schools.[24][25][26][27]

School districts[edit]

- See also: School board elections portal

District types[edit]

New York contains seven types of school districts:[28][29]

- Central districts are traditional school districts that provide K-12 educational services to students. They can be created through mergers of common, union free or other central districts.

- Central high school districts provide secondary education services to common or union free district students. The governing body is made up of appointed representatives from the constituent school districts it serves.

- City districts are traditional school districts that provide K-12 educational services to students within the boundaries of the city limits. The city must have a population of fewer than 125,000 residents to receive this classification.

- Enlarged city districts are identical to city districts except that the boundaries of the district extend beyond the city limits.

- Dependent city districts are in cities with a population greater than 125,000 residents. The district operates as part of the municipal government, including the school district's funding. The governing body does not have the power to levy taxes or incur debt in a dependent city district. The five dependent city districts, also known as the "Big 5," are Buffalo, New York City, Rochester City, Syracuse City and Yonkers.[30] Buffalo, Rochester and Syracuse have elected governing bodies. The governing body in New York City is appointed by the mayor and the borough presidents, and the governing body in Yonkers is appointed by only the mayor.

- Common districts are the oldest form of school district in New York. Common districts are not legally authorized to establish high schools, so common districts send their students to high schools in a neighboring district or districts. The governing body can consist of either one individual or a board of three members. Voters may decide to change the size from one to three or vice versa at annual meetings.

- Union free districts consist of two or more common districts merged together. The purpose was initially to provide high schools to students, but some union free districts operating today only provide K-8 educational services and still send their students to high schools in a neighboring district or districts.

School board composition[edit]

New York school board members are generally elected by residents of the school district, although school board members in New York City and Yonkers are appointed. New York school board elections typically follow one of these three methods, or a mixture thereof:

- At-large: All voters residing in the school district may vote for any candidates running, regardless of geographic location.

- Trustee area: Only voters residing in a specific geographic area within the school district may vote on certain candidates, who must also reside in that specific geographic area.

- Trustee area at-large: All voters residing in the school district may vote for any candidates running, but candidates must reside in specific geographic areas within the school district.

School boards typically consist of one to nine members, although there are exceptions. Most board members serve three-, four- or five-year terms, although there are exceptions to that, as well.[31]

Term limits[edit]

New York does not impose statewide term limits on school board members.[32]

Elections[edit]

- See also: New York school board elections, 2022

The table below contains links to school board elections covered by Ballotpedia in 2022 in this state. This list may not include all school districts with elections in 2022. Ballotpedia's coverage includes all school districts in the 100 largest cities by population and the 200 largest school districts by student enrollment across the country.

Our coverage scope for local elections continues to grow, and you can use Ballotpedia's sample ballot tool to see what school board elections we are covering in your area.

Editor's note: Some school districts choose to cancel the primary election, or both the primary and general election, if the number of candidates who filed does not meet a certain threshold. The table below does not reflect which primary or general elections were canceled. Please click through to each school district's page for more information.

| 2022 New York School Board Elections | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Primary | General Election | General Runoff Election | Regular term length | Seats up for election | Total board seats | 2017-2018 enrollment |

| Buffalo Public Schools | N/A | 11/8/2022 | N/A | 3 or 5 years | 6 | 9 | 1,988 |

| Lackawanna City School District | N/A | 5/17/2022 | N/A | 3 | 2 | 7 | |

Path to the ballot[edit]

To qualify for the ballot as a school board candidate in New York, a person must be:

- 18 years of age or older

- Able to read and write

- A qualified voter in the district

- A resident of the district for between 30 days and three years before the election, depending on the district

A person must not be:

- Employed by the school district

- Married or related to a current member of the board

The process of running for office as a school board candidate begins with filing nomination papers with the school district clerk. The number of petition signatures required varies from a flat number of 100 qualified voters in the district to either 25 qualified voters or two percent of the number of voters in the previous election, whichever number is greater. Nominating petitions must be filed with the district clerk either 30 days or 20 days before the election, depending on the district.[31]

Campaign finance[edit]

New York requires all school board candidates to file three campaign finance reports with the district clerk during the election cycle. If a candidate's expenditures exceed $500, the candidate must file an additional report with the New York Commissioner of Education.[31]

Recent legislation[edit]

The following is a list of recent education bills that have been introduced in or passed by the New York state legislature. To learn more about each of these bills, click the bill title. This information is provided by BillTrack50 and LegiScan.

Note: Due to the nature of the sorting process used to generate this list, some results may not be relevant to the topic. If no bills are displayed below, no legislation pertaining to this topic has been introduced in the legislature recently.

Education ballot measures[edit]

- See also: Education on the ballot and List of New York ballot measures

Ballotpedia has tracked the following statewide ballot measures relating to education.

- New York Proposal 2, Small City School Districts Excluded from Debt Limits (2003)

- New York School Bonds, Proposal 3 (1997)

- New York Bonds for School Technology Act, Proposal 3 (2014)

- New York Real Estate Taxes and School Districts, Proposal 5 (1985)

- New York Filling Vacancies on the Board of Education, Proposition 8 (1977)

- New York State Lotteries for Education, Amendment 7 (1966)

- New York Contract Indebtedness for the Buffalo City School District, Amendment 9 (1966)

- New York State Liability of Construction of Buildings at Universities, Amendment 6 (1961)

- New York City Bond for School Construction, Amendment 4 (1959)

- New York State Debt for Expansion of the State University, Amendment 2 (1957)

In the news[edit]

The link below is to the most recent stories in a Google news search for the terms New York education policy. These results are automatically generated from Google. Ballotpedia does not curate or endorse these articles.

See also[edit]

- Historical public education information in New York

- New York state budget and finances

- New York Department of Education

- List of school districts in New York

- School choice in New York

- Charter schools in New York

- New York

- Education Policy in the U.S.

External links[edit]

- New York State Education Department

- New York State Board of Regents

- New York State School Boards Association

- New York Charter Schools

- New York Education Budget

- New York Education Audit Reports

- New York Public School Ratings by PSK12

- New York Public School Ratings by Great Schools

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ United States Census Bureau, "U.S. School System Current Spending Per Pupil by Region: Fiscal Year 2020," May 18, 2022

- ↑ National Center for Education Statistics, "Fast Facts: High school graduation rates," accessed September 28, 2022

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 United States Department of Education, ED Data Express, "State Tables," accessed May 13, 2014

- ↑ ACT, "2012 ACT National and State Scores," accessed May 13, 2014

- ↑ Commonwealth Foundation, "SAT Scores by State 2013," October 10, 2013

- ↑ StudyPoints, "What's a good SAT score or ACT score?" accessed June 7, 2015

- ↑ United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, "Common Core of Data (CCD), State Dropout and Graduation Rate Data File, School Year 2010-11, Provision Version 1a and School Year 2011-12, Preliminary Version 1a," accessed May 13, 2014

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue: "Petition for a writ of certiorari," accessed July 3, 2019

- ↑ Supreme Court of the United States, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, decided June 30, 2020

- ↑ NASBO, "State Expenditure Report," accessed July 2, 2015

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 U.S. Census Bureau, "Public Education Finances: 2013, Economic Reimbursable Surveys Division Reports," accessed July 2, 2015

- ↑ National Center for Education Statistics, "Revenues and Expenditures for Public Elementary and Secondary Education: School Year 2011–12 (Fiscal Year 2012)," accessed July 2, 2015

- ↑ Maciver Institute, "REPORT: How much are teachers really paid?" accessed October 29, 2014

- ↑ United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, "Table 211.60. Estimated average annual salary of teachers in public elementary and secondary schools, by state: Selected years, 1969-70 through 2012-13," accessed May 13, 2014

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 New York State Education Department, "About the New York State Education Department," accessed June 2, 2014

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ Thomas E Fordham Institute, "How Strong Are U.S. Teacher Unions? A State-By-State Comparison," October 29, 2012

- ↑ Center for Union Facts, "New York teachers unions," accessed September 4, 2009

- ↑ Education Week "Quality Counts 2014," accessed February 19, 2015

- ↑ The New York Times, "Obstacles Seen for de Blasio’s Preschools Plan," August 28, 2013

- ↑ The New York Times, "State Budget Deal Reached; $300 Million for New York City Pre-K," March 29, 2014

- ↑ Education Week, "N.Y.C. Hustles to Make Use of Pre-K Windfall," April 7, 2014

- ↑ The Wall Street Journal, "Head of New York City's Pre-K Expansion Has Daunting Job Ahead," May 18, 2014

- ↑ The Mighty, "New York First State to Require Mental Health Education in Schools," February 1, 2018

- ↑ Associated Press, "NY law will require mental health education in schools," October 3, 2016

- ↑ Times Union, "After long battle, mental health will be part of New York's school curriculum," January 27, 2018

- ↑ Pew, "Many Recommend Teaching Mental Health in Schools. Now Two States Will Require It." June 15, 2018

- ↑ United States Census Bureau, "New York," accessed July 11, 2014

- ↑ New York State Education Department, "Guide to the Reorganization of School Districts in New York State," accessed July 11, 2014

- ↑ Conference of Big 5 School Districts, "Member Districts," accessed September 8, 2016

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 New York State School Boards Association, "Running for the School Board," accessed July 11, 2014

- ↑ National School Boards Association, "Survey of the State School Boards Associations on Term Limits for Local Board Members," accessed July 8, 2014

KSF

KSF