Chemical warfare in World War I

From Citizendium - Reading time: 3 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 3 min

Poison gas was the most controversial weapon of World War I-- indeed, next to nuclear weapons, among the most controversial weapons of the 20th century.

In 1899, the Hague Peace Conference outlawed "asphyxiating or deleterious gases." Ignoring the prohibition, German chemists, led by Nobel-prize winner Fritz Haber, promised that chlorine could break the stalemate in the trenches. Germany dominated the world's young chemical industry. Chlorine was an important industrial chemical; the technology to manufacture and store large quantities was well known. On the Western front, 3% of all casualties were attributed to gas; 1,200 Americans definitely died from it. Both sides mixed gas shells with high explosives. Seriously affected patients required elaborate nursing care and extended bed rest to avoid the danger of pneumonia, but over 90% eventually recovered. However, poison gas a debilitating psychological weapon. Soldiers hated the masks because of the claustrophobia, the difficulty in getting enough oxygen for strenuous movement, and the garbling of voices and commands. By 1918, the continuous use of masks was a major contributor to combat fatigue--a psychological condition in which the soldier loses control of his emotions and became a liability in combat. Poison gas never won a battle, but by forcing soldiers to mask, it slowed down the tempo of operations, made coordination difficult, affected morale, and increased the vulnerability of soldiers to artillery and machine gun fire. Germany favored gas because it was on the defensive on the Western Front from late 1914 to early 1918, and its large, sophisticated chemical industry delivered a high-quality product.

Some historians feel that the true effects of gas have been exaggerated in post-war accounts; no battle was decided by the use of poison gas, and the number of actual casualties inflicted was a tiny fraction of the overall number.[2]

The first attack using poison gas came in 1915 at St. Julien during the Second Battle of Ypres on the night of 21-22 April. The Germans opened thousands of cylinders and waited for the wind to carry the emitted gas into the Allied lines. Two French divisions (the 45th Algerian and 78th Territorial) fled in panic. Astonished by the results the new weapon achieved, the Germans were unprepared to take advantage and advanced slowly into the four-mile gap in the line. The Canadian Division was hastily assembled and counter-attacked, restoring the front over the course of several days, at the cost of about half the division.

Within three days of the first poison gas attack in 1915, Allied doctors had developed a simple but adequate mask and shipped 200,000 to the front; air that was breathed through ordinary washing soda was safe. By 1916, the British soldiers carried an excellent rubber face mask with glass eyepieces and a tube connecting it to separate respirators. The new masks gave practically 100% protection--but only when they were worn. The Russians never obtained an adequate supply and suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties. Death came in a matter of days due to lack of oxygen caused by pulmonary edema--the lungs filled up with fluids and the victims drowned in their own secretions. One effective treatment was therapeutic phlebotomy: surgeons cut a vein and pumped out 20- 25 ounces of blood.

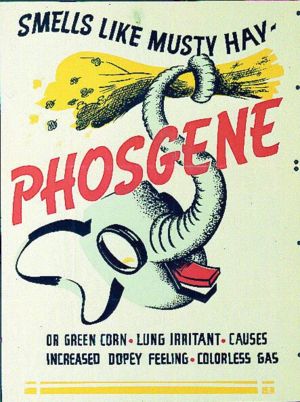

In response to the use of chlorine gas by the Germans, the Allies developed their own chemical weapons. Chemists invented 18 new gases that were more effective than chlorine, and also masks to neutralize them. Phosgene ("Green Cross", the Germans called it) like chlorine, attacked the lungs, only more quickly--without a mask a victim had one minute to live--but it evaporated in 30 minutes. Release by cylinders proved unwieldy and dangerous, so by 1916 belligerents on both sides turned to artillery shells, each of which could land a few pounds of liquefied poisons on targets far behind the trenches on posts that had been spotted by airplane. On the front lines, gas was a harassment but not a tactical factor. A huge amount of gas had to be released in a short period in order to be effective, yet the same amount of high explosive would do much more damage.

The Germans introduced mustard gas ("Yellow Cross") in July 1917. While not a killer, it caused severe blisters in the lungs and on exposed skin that could temporarily blind or incapacitate for weeks or months. Mustard gas (actually a liquid) evaporated very slowly, so elaborate decontamination routines were necessary to wash off humans, equipment and terrain. Late in the war, Berlin invented arsenic compounds ("Blue Cross", ) which, while not lethal, caused uncontrollable sneezing or nausea that forced victims to remove their masks, thus exposing them to lethal gases.

KSF

KSF