Chiropractic

From Citizendium - Reading time: 28 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 28 min

Chiropractic is a complementary and alternative health care profession that aims to heal using manual therapies on the spine and extremities. While the majority of today's chiropractors treat mostly musculoskeletal problems, their original defining theory is that they can affect general body function by locating and correcting what they call subluxations of the spine. Subluxations are treated with "spinal adjustments" that are intended to improve body posture and joint mobility. As a fundamental concept in chiropractic, subluxations were originally conceived as obstructions to the full flow of "innate intelligence" from mind to body. Today, chiropractic education is replacing that term, innate intelligence, with emerging concepts related to the higher functions of the nervous system. The spine remains the focus of chiropractic therapy and spinal adjustments to alleviate subluxations are still used by the profession in an effort to improve general health. Although chiropractic manipulations have been shown to be efficacious for some types of back pain, treatment of most other health related conditions using chiropractic therapy has not been accepted by health science. That rejection is not simply based on a lack of compelling clinical evidence, but also because health science does not accept the chiropractic concept of subluxation, or innate intelligence, as part of human biology.

Chiropractic has won public acceptance and has become the most established of the alternative medical professions in the developed western world. Chiropractic can claim both a very high rate of satisfaction among its patient population, along with a very low rate of complications attributed to its treatment.

(In the health sciences, subluxation always means that there is a physical dislocation such that the part is completely out of place. In chiropractic subluxations, this is almost never the case. Unless otherwise specified, the word 'subluxation' in this article uses the chiropractic definition.[1])

Introduction[edit]

Chiropractic was founded in 1895 by Daniel David Palmer (D. D. Palmer). Palmer practiced magnetic healing in the rural heartland of the USA, without medical training. By accident or design, he treated a deaf friend to correct a spinal distortion and noted that the man's hearing subsequently improved. Palmer (who had no formal education in science), conceived of a new theory of disease. Taking a vitalistic approach, he proposed that a misaligned spine might impair the flow of natural 'healing power' (which he later coined "Innate Intelligence") from mind to body, and named these theoretical misalignments "subluxations". Speculating that the nerve carried this energy, he considered that blockage of the nerve might allow 'dis-ease' or disharmony, and that healing might occur if the block was removed. He later acknowledged, however, that no other adjustment had been able to reproduce the results of that first adjustment. Today, chiropractors and physicians agree that Chiropractic is not a treatment for deafness.

Palmer's early methods were not novel; they had been used by bonesetters since the time of Hippocrates, but he further developed methods of 'cracking' the back which he called spinal adjustments. He likened his methods to watering a garden, the misaligned spinal joint was like a crimp in a hose that slows the flow of water: uncrimp the hose, the flow returns, and the garden will flourish.[2] While chiropractors have mostly abandoned the 'pinched garden hose theory', some still use the metaphor to explain the concept of subluxations to their patients. Today, chiropractors use several types of manual therapies and spinal adjustments mostly to treat conditions such as low back pain, neck pain and headaches. Some no longer use the word subluxation to describe the spinal conditions that they treat, but most still think that the spine has a role in all health and disease.

Palmer's theories have not been accepted outside chiropractic, but the efficacy of chiropractic for some conditions has been supported by large studies published in the health science literature. Chiropractic manipulation (a form of spinal adjustment) relieves back pain as well as conventional treatment with physical therapy, and patients tend to be more satisfied with chiropractic care (even though chiropractic care does not include the use of pain-relieving drugs). The overall cost of back pain care is similar for both types of treatment courses. However, for general medical conditions, like allergy, there is no agreement that chiropractic is any more efficacious than placebo. Chiropractic treatment of adults (and especially children) for these general medical conditions has been contentious both within the profession and between chiropractors and physicians.

There are about 70,000 chiropractors in the USA, 5000 in Canada, 2500 in Australia, 1300 in the UK, and smaller numbers in about 50 other countries. Some chiropractors specialize in musculoskeletal problems or sports injuries, others combine chiropractic with physiotherapy, nutrition, exercise, or other complementary and alternative (CAM) methods. Chiropractors do not prescribe drugs or perform surgery, and do not recommend 'over-the-counter' medications. They believe that this is the province of conventional medicine, while their role is to pursue drug-free alternative treatments in an effort to avoid the need for surgery.[3]

Chiropractic in practice[edit]

Most patients who visit a chiropractor for the first time do so for low back pain, neck pain and headaches[4]. Chiropractors will take note of the patient's chief complaint, as well as a survey for symptoms arising from other body systems. A thorough patient and family history, review of organ systems and a physical examination are part of a complete evaluation by a chiropractor. A chiropractic evaluation is as professional as an evaluation by a health science practitioner, but is no more than superficially similar to a medical history and physical as done by a physician. A chiropractic evaluation is not designed to detect medical diagnoses or evaluate medical illness. These are not recognized as such in fundamental chiropractic philosophy. Instead, the chiropractic evaluation is aimed to make chiropractic diagnoses, rule out red flags for serious health conditions, and to formulate a treatment plan.

Posture and spinal function are carefully assessed using chiropractic methods, and laboratory tests to evaluate blood and urine may also be performed. Additionally, chiropractors may sometimes perform X-rays, order MRI, CT scans, or other imaging studies, or might refer the patient to other alternative health care providers, or to physicians, for tests. What are some of the chiropractic methods commonly used to identify subluxations or suboptimal spinal segment mobility? When examining the patient, the chiropractor palpates the spine to feel the contour of the deep muscles that run between the vertebrae (the multifidus and erector spinae muscles) and assesses their symmetry and flexibility. If an area feels tight, hard or bony, the chiropractor checks to see if the vertebral joint below it moves properly. If it is stiff or unusually mobile, the area is identified as a 'trouble spot' or subluxation, which might reflect a new or an old injury, or a postural abnormality. Often, the patient identifies that same spot by pain felt during the palpation. The chiropractor is likely to suspect that this joint might cause problems if neglected, and will adjust it in an effort to prevent these and alleviate present symptoms.

After making a diagnosis, and discussing it with the patient, the chiropractor obtains informed consent, and treats according to guidelines set by national and local consensus panels, such as the Mercy Guidelines. In accordance with these, no ethical chiropractor will ever claim to be able to cure cancer, metabolic disorders such as diabetes, or infectious diseases, although they might treat patients who have these conditions, to relieve pain or provide a feeling of well-being.

The most common adjustment involves manipulating the spine with a fast but gentle thrust that usually causes a 'popping' sound. The sound is thought to be from a form of cavitation in the fluid-filled diarthrodial joints. During a manipulation, the force applied separates the surfaces of the encapsulated joint cavity, creating a relative vacuum within the joint space. In this environment, gases that are naturally dissolved in all bodily fluids form a bubble (as when gas is released from a carbonated drink when it is opened), creating a rapid vibration, and a sound is heard. The effects of the bubble within the joint continue for hours while it is slowly reabsorbed. During this time, the joint is able to move more freely and, in theory, stimulates the nerves surrounding the joint capsule.

Other techniques for analyzing and adjusting subluxations have been developed since the first chiropractic treatments, and not all include cavitation-type spinal manipulation. Some require specialized tools or tables, the 'Activator Technique', for instance , uses a hand-held percussion instrument, the 'Thompson Technique' uses a special table with sections that drop, and the Cox Flexion Distraction technique uses a table that tractions the lower back and is specifically for treating lumbar disc herniations and facet-related injuries. There are literally hundreds of methods that are now called spinal adjustments.[5]

Subluxation and Innate Intelligence[edit]

Chiropractors are still committed to the healing art begun by Palmer, but some feel that the 19th century concepts of Innate Intelligence and subluxation are too vague to remain useful. In 1998, Lon Morgan wrote that the concept of Innate Intelligence originates in "borrowed mystical and occult practices of a bygone era"; he described it as untestable and unverifiable, and harmful to progress within the profession. [6] Others argue that these concepts remain useful as metaphors for physiological processes that are poorly understood, and because they help them to see their patients as more than the 'sum of their parts'. They believe that trying to explain all the complex processes that combine to make a human being function in terms of biology misses things that are important for understanding what makes him or her healthy. Meridel Gatterman said of 'subluxation', "To some it has become the holy word; to others, an albatross to be discarded ... Why then do we persist in using the term when ... the concept that once helped to hold a young profession together now divides it? ...The obvious answer is: The concept of subluxation is central to chiropractic."[7] Anthony Rosner, former head of the Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research, suggested that there is no reason to discard the concept of subluxation if it is treated as a 'provisional' concept that will undergo continuous modification. [8]

Chiropractic approach to healthcare[edit]

Contemporary chiropractors take diverse approaches to patient care, ranging from a "holistic" and naturopathic approach to being integrated as a musculoskletal specialist in the conventional medical model. These differences are reflected in different professional associations.[9][10]

- Traditional Straights hold that subluxation is a risk factor for most diseases. They do not try to diagnose complaints, which they consider to be secondary effects; instead, they screen patients for 'red flags' of serious disease. Many traditional straights belong to the International Chiropractors Association and offer general health care to both adults and children. Traditional straights teach their patients that vaccinations in childhood are dangerous, and are sceptical of whether either pharmacology or medical care offer any true benefits in health care.

- Mixers use more diverse diagnostic and treatment approaches, including naturopathic remedies and physical therapy devices. Many belong to the American Chiropractic Association, and all the major groups in Europe are part of the European Chiropractors Union.

- Objective Straights focus on correcting subluxations. They typically do not diagnose patient complaints, or refer to other professionals, but they encourage their patients to consult a medical physician "if they indicate that they want to be treated for the symptoms they are experiencing or if they would like a medical diagnosis to determine the cause of their symptoms". Many belong to the Federation of Straight Chiropractic Organizations and the World Chiropractic Alliance.

- Reform chiropractors, also a minority, are mostly mixers who use manipulation to treat osteoarthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions. They prefer to integrate their skills into contemporary medicine and do not subscribe to Palmer philosophy or vertebral subluxation theory. Reform chiropracters tend not to use CAM methods in their practice.

Chiropractic education, licensing and regulation[edit]

In the USA, students today must meet a minimum prerequisite course of study of 90 semester hours from an accredited college or university, including biology, psychology, and physics before matriculating into chiropractic school. Chiropractic programs entail at least 4,200 hours of instruction in subjects including organic chemistry, biochemistry, dermatology, radiology, psychology, pathology , physiology, orthopedics, neurology, geriatrics, physiotherapy, nutrition, and anatomical studies including 8 months of human dissection. Students undertake a research project in their third year. The final two years cover manipulation and spinal adjustment and give experience in physical and laboratory diagnosis. After this, to qualify for licensure, graduates must pass four examinations from the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners and satisfy State-specific requirements.

There are now 17 chiropractic colleges in the USA, four in the UK, two in Canada and another 9 internationally. Chiropractic colleges also offer postdoctoral training leading to 'diplomate' status in particular specialties. In the USA, this training is overseen by the Council on Chiropractic Education. Each state has its own licensing board, overseen by a Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards, which handle any necessary disciplinary actions. Unlike medicine, in the USA, laws governing the practice of chiropractic vary from state to state and, as a result, procedures used by chiropractors vary as well. In the UK, chiropractic is regulated by the General Chiropractic Council (GCC), a statutory body with regulatory powers established by an Act of Parliament in 1994 [11]. The GCC is charged with maintaining standards and enforcing professional discipline, and it is illegal for anyone to represent themselves as a chiropractor in the UK unless they are registered with the GCC.

The origin of the chiropractic profession[edit]

- See Chiropractic history for a more detailed account

In the USA, the 19th century saw the rise of remedies in the form of family-owned patent medicine and the nostrum trade. The addictive or toxic effects of many of these remedies, especially morphine and mercury-based cures, and the harsh laxatives and emetics, prompted the rise of the alternative remedies of homeopathy and eclectic medicine. These mild treatments were better tolerated and were usually at least no more ineffective.

By 1885, purveyers of scientific medicine, herbalism, magnetism and leeches, lances, tinctures and patent medicines were all in competition. Claims among the healing professions proliferated, and few places in the country regulated the practice of medicine or health care. Often, neither the patients or practitioners knew much about either the causes of, or cures for, illness. Quack cures were becoming more common and were mostly unregulated, as was the majority of medical practice, except in some Eastern regions.

It would not be until the first decades of the 20th century that Medicine in the USA, as a whole, was transformed into an early form of what we now think of as 'modern medicine'. That was accomplished by limiting the medical license only to graduates of medical schools that required rigorous scientific and clinical training, along with other requirements. Chiropractic was born just as modern medicine was taking first firm root, during a time when allopaths, homeopaths and other sects of medicine flourished, along with the purveyors of patent medicine, magnetic healing, and other alternative methods.

DD Palmer opened his office of magnetic healing in Davenport, Iowa in 1886. Although he was not a physician, healers at that time, especially in that part of the country, often had no medical training. On September 18, 1895, he treated a deaf janitor, Harvey Lillard. Lillard had been virtually deaf for seventeen years, ever since, while working in a cramped area, he had felt a 'pop' in his back. Palmer found a sore lump that indicated spinal misalignment; he corrected the misalignment, after which Lillard could "hear the wheels of the horse-drawn carts" in the street below. (Lillard's daughter related the incident differently. She said that her father was joking with a friend in the hall outside Palmer's office when Palmer joined them. As Lillard reached the punchline, Palmer, laughing heartily, slapped him on the back, and a few days later, his hearing seemed better.)

Palmer himself described the next phase: "I had a case of heart trouble which was not improving. I examined the spine and found a displaced vertebra pressing against the nerves which innervate the heart. I adjusted the vertebra and gave immediate relief -- nothing 'accidental' or 'crude' about this. Then I began to reason if two diseases, so dissimilar as deafness and heart trouble, came from impingement, a pressure on nerves, were not other disease due to a similar cause? Thus the science (knowledge) and art (adjusting) of Chiropractic were formed at that time."

Palmer asked a friend, the Reverend Samuel Weed, to help him name his discovery; he suggested combining the words cheiros and praktikos (meaning 'done by hand'). In 1896, he added a school to his magnetic healing infirmary and began to teach others the new "chiropractic"; it would become the Palmer School (now College) of Chiropractic. Palmer's first descriptions for chiropractic were very similar to Andrew Still's earlier principles of osteopathy: both described the body as a 'machine' whose parts could be manipulated to effect a drugless cure. However, Palmer said that he concentrated on reducing 'heat' from friction of the misaligned parts, while Still claimed to enhance the flow of blood. Palmer would later clarify that his method of using the short levers of the spinous processes to perform his maneuvers was unique to chiropractic, as well as the assertion that his effects were on nerves rather than on the artery.

Chiropractic; the early years[edit]

- See also: Chiropractic history

The American Medical Association (AMA) was formed in 1847 to raise the standards of medical education. This activity was impossible during the years of the Civil War and aftermath, and reform of medical education did not come for more than another 60 years. During much of that period, there was raw competition between various healers, and sects of physicians, who were engaged in the business of patient care as a commercial enterprise, and no more than spotty regulation of health care that was administered according to regional location, usually by state laws.

In 1899, a Davenport physician, Heinrich Matthey, began a campaign to change the law in Iowa to prevent 'drugless healers', such as osteopaths and chiropractors, from practicing there, arguing that their training and education was not sufficient to ensure the public welfare. Matthey had recently received his own medical education in Germany[12] under the system that that Abraham Flexner, the educator whose report was soon to play a pivotal role in the reform of medical schools in the USA, admired as excellent, especially in science. Osteopathic schools responded to such criticism by developing a program of college inspection and accreditation. DD Palmer, who had no medical education, and whose school had just graduated its 7th student, insisted that his graduates did not need the same training as medicine, as they did not prescribe drugs. Nevertheless, he was arrested and convicted for claiming that he could cure disease when he had no license to practise either medicine or osteopathy.

In the early 20th century, intense political pressure finally resulted in medical boards in almost every state, and these required licentiates to have a diploma from an AMA-approved college. By 1906, the AMA had drawn up a list of schools whose standards they considered to be unacceptable, and in 1910, as a result of the Flexner Report, dozens of private medical and homeopathic schools were closed. These schools all had curriculums that were condemned as lacking university level training in laboratory science, and as lacking sufficient supervised clinical training in hospital wards and dispensaries. Except for a few osteopathic and homeopathic based schools, all of the sects of medicine were driven out. Medicine in the USA entered a new era; medical education was now primarily university based, all schools set high admission standards, and training in science and clinical medicine was uniformly required. At the same time, licensing requirements for medical practice were strengthened; all over the country, public health standards were set by physicians with advanced knowledge of bacteriology and laboratory science, and these physicians assumed leadership in the medical profession. So-called 'quack doctors' were purged from American medicine in various campaigns within the profession over the next decades.

DD Palmer was unable to develop chiropractic as a viable health care profession in this difficult era. After his arrest and conviction, Palmer closed and sold his school to his son BJ. DD moved on to help found several small chiropractic schools throughout the midwest, but would never regain control of the profession. Although DD is considered the Founder of chiropractic, BJ's leadership in the next decades led him to be known as the 'Developer of Chiropractic'.

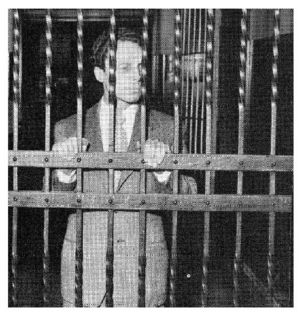

BJ Palmer, who was, by all accounts, extremely bright, charismatic, and energetic, was instrumental in founding the 'Universal Chiropractic Association' (UCA) to provide legal defense for chiropractors; its first case was in 1907, when Shegataro Morikubo DC of Wisconsin was charged with unlicensed practice of osteopathy. In that case, attorney and senator Tom Morris, who had attended McGill University medical school but never finished, legally differentiated chiropractic from osteopathy by the differences in the philosophy of chiropractic's 'supremacy of the nerve' and osteopathy's 'supremacy of the artery'. Morikubo was freed, and the victory shaped the development of chiropractic, which then marketed itself, under BJ Palmer's direction, as a science, an art and a philosophy. There would be over fifteen thousand arrests of chiropractors who refused to pay fines for practicing medicine without a license in a campaign to draw attention to the issue.[12]

BJ Palmer developed the field of chiropractic during his long and notable life, and wrote more than 70 books [13]. A successful entrepreuneur, he was also an adept communicator, and reached out to the public through his radio broadcasts over the decades. BJ Palmer believed that relief of subluxations was a cure for, by and large, all disease. His influence in chiropractic, along with his extreme views against both vaccination and the germ theory of infectious disease, made him, along with other anti-vaccination advocates, a target of the frustration of public health reformers. During the progressive era of the 1920's, these scientists and physicians imposed a new standard of public health throughout the USA. Despite their success, frustration at the persistent resistance to their efforts was a noted complaint.[13].

The struggle from within[edit]

Laws that protected the chiropractor's right to practice were eventually introduced in every state in the USA, but only after a struggle. That came about when licenses to practice chiropractic were granted, and practicing chiropractors accepted regulation. Paradoxically, it was disagreement between chiropractic groups that hindered the process most. While Medicine finally united behind regulation in its own profession, with licenses to practice granted only to those who could meet strict requirements, unlicensed chiropractors - especially those who, like BJ Palmer, claimed to cure all or most disease, were subject to arrest and imprisonment for practicing medicine without a license. Even with widespread arrests, the young profession of Chiropractic was divided over the question of regulating itself. Not only were there differing opinions as to whether licenses to practice chiropractic were needed, but there were even different attitudes towards what constituted the practice of Chiropractic. Some chiropractors had continued to add techniques to their practices, such as naturopathy remedies or physical therapy and electrical modalities. Established straight school chiropractors, like BJ Palmer, worked continuously to prevent the acceptance of such additions, fighting to maintain the purity of chiropractic. Initially, the Universal Chiropractic Association (UCA), with Morris at the helm and BJ Palmer as treasurer, lobbied against state regulation, claiming that it would lead to medical control of the profession.

As licensing for health professionals swept the nation, and litigation against chiropractors remained an everyday event, more and more chiropractors felt that accepting regulation was the only way to keep them out of prison. Why not follow the osteopathic route and improve educational standards, and accept licensure? Perhaps even meet standards for the practice of Medicine? BJ Palmer voiced his concern that absorption by Medicine would result in losing the vitalistic Chiropractic philosophy that kept it a drugless healing profession. With the formation of national standards for education in basic sciences, the UCA conceded, and accepted licensure as desirable for the profession. Now the argument centered on what would be required for a license to practice chiropractic. BJ Palmer insisted that examining boards should be composed exclusively of straight chiropractors (not mixers who used other remedies, as well), and that the education required for licensure be the same as the graduation requirements of the Palmer School, so that the profession would be consolidated around the "Fountainhead" school, his school. In 1922, the UCA presented a 'model bill' to states that had not yet settled on licensing requirements for chiropractors. This bill tried to assure that chiropractic would be practiced straight rather than mixed with other techniques. At the same time, the UCA began to 'clean house' of mixers, warning the state chapters to purge their mixing members or face competition from a new 'straight' association.[14]

In response, mixer chiropractors founded the American Chiropractic Association (ACA); its founding principle was to give control of professional practice to practicing chiropractors rather than the schools of chiropractic. Its growth was initially stunted by its decision to recognize physiotherapy and other modalities as related to chiropractic, but, in 1924, a disagreement within the UCA turned the tide. BJ Palmer was still trying to purge mixers from chiropractic, and he saw a new invention by Dossa D. Evans, the Neurocalometer, as the answer. As the owner of the patent on the Neurocalometer, he planned to produce just 5000 instruments, and lease them only to members of the UCA. He then claimed that the Neurocalometer was the sole way to accurately locate subluxations, preventing over 20,000 mixers from being able to defend their method of practice. [15]

There was uproar among practicing chiropractors, and even Tom Morris, BJ Palmer's old ally and president of the UCA, displayed his dismay by resigning. BJ Palmer resigned as treasurer, ending his relationship with the UCA, and moved on to form the 'Chiropractic Health Bureau' (today's ICA) along with his staunchest supporters. In 1930, the ACA and UCA combined to form the 'National Chiropractic Association' (the precursor to today's ACA), creating the largest mixer association and made John J Nugent responsible for raising educational standards; his zeal earned him the nickname 'Chiropractic's Abraham Flexner' from admirers and 'Chiropractic's Anti-christ' from adversaries. The CES became today's Council on Chiropractic Education, chiropractic's accrediting body. [14]

The American Medical Association's plans to eliminate chiropractic[edit]

For fifty years after the Flexner Report, organized medicine and academic medicine (the teaching and research faculty of the medical schools and university associated residency training programs) fought to keep a high standard of education and practice within medicine. Licenses to practice medicine as a physician were restricted, by state regulation, to holders of the MD or DO degree who also had at least a year of accredited clinical training. There was a sense that the future of the healing arts lay in science, and that scientific research might eventually conquer disease. Such hopes were strengthened by successes like the isolation and culture in scientific laboratories of the viruses that cause poliomyelitis (polio) [15], which paved the way for Jonas Salk[16] to develop an effective polio vaccine. The introduction of polio vaccines in the USA was followed by a massive reduction in the incidence of this devastating disease, leading to fresh confidence that, contrary to the precepts of chiropractic, drug interventions could indeed be a very effective way of combating major disease. While science was embraced by the AMA, health remedies that lay outside of medicine were viewed as anachronistic "quackery". Although many clinical practices within medicine were based on empiric teaching rather than science, other empiric practices, like chiropractic, were disdained [16].

The polio vaccine was administered to the American public in mass vaccinations over the mid-1950's. Chiropractic was far from the only group outspoken in their warnings against complying with vaccinations, but chiropractic professionals, as a profession, condemned mass use of the vaccine. BJ Palmer, through his radio speeches, was particularly committed to spreading that message. Some physicians were likely to resent the success of chiropractors as competitors in practice, but the physicians who showed the most committed campaign against the chiropractors were in the academic and organizational elite of the medical profession. "Morris Fishbein, secretary of the American Medical Association (AMA) and editor of its journal from 1924 to 1949, was one of the most influential of the antichiropractic forces, grouping chiropractic along with antivivisectionism and osteopathy as "nonmedical cults" . [17]

During this time, even as epidemics of infantile paralysis were finally stopped by mass vaccination, Palmer remained a vocal opponent of vaccination. Chiropractic had claimed efficacy at treating the effects of polio, and he, along with the profession, warned that vaccination was not only not useful against polio but worsened the disease. By that time, BJ Palmer was elderly and his views on infectious disease appear to have survived intact from his youth. As the son of the founder and a seminal force in its development, BJ Palmer's public expression of those views must have been another blot on Chiropractic in the eyes of scientific medicine.

By the late 1950s, a reform movement began within chiropractic. Shortly after the death of BJ Palmer in 1961, a second generation chiropractor, Samuel Homola, proposed that chiropractic should focus on conservative care of musculoskeletal conditions. "If we will not develop a scientific organization to test our own methods, organized medicine will usurp our privilege. When it discovers a method of value, medical science will adopt it and incorporate it into scientific medical practice." Homola's membership of the ACA was not renewed, and initially his views were rejected by both straight and mixer associations.[18]

In 1963, the AMA formed a 'Committee on Quackery' that began a campaign to eliminate chiropractic, and set out to forbid its members from working with chiropractors on the basis of the AMA 'Principles of Medical Ethics'. Until 1980, these stated that "A physician should practice a method of healing founded on a scientific basis; and he should not voluntarily professionally associate with anyone who violates this principle." Many chiropractors saw this as a reflection of business rivalry between organised medicine and chiropractic, and as a result, in 1976, a Chicago chiropractor, Chester Wilk, and three others brought an antitrust suit against the AMA (see Wilk et al vs AMA et al.). In 1987, the Federal Appeals Court found the AMA guilty of conspiracy and restraint of trade. The AMA lost its appeal to the Supreme Court.

In her judgement[19], Judge Susan Getzendanner strongly criticised the AMA campaign, saying that the AMA had taken: "active steps, often covert, to undermine chiropractic educational institutions, conceal evidence of the usefulness of chiropractic care, undercut insurance programs for patients of chiropractors, subvert government inquiries into the efficacy of chiropractic, engage in a massive disinformation campaign to discredit and destabilize the chiropractic profession and engage in numerous other activities to maintain a medical physician monopoly over health care in this country." She described the Committee on Quackery as essentially comprising doctors who had volunteered to serve because of their belief that chiropractic should be eliminated. Evidence was given to the Committee that chiropractic was more effective than the medical profession for certain problems, and that some medical physicians believed that chiropractors were better trained to deal with musculoskeletal problems than most medical physicians. However, the Committee did not follow up any of these studies or opinions. At the trial, most witnesses who appeared on behalf of the AMA agreed that some chiropractic treatment is efficacious. The court recognized that some chiropractic practices lacked a scientific basis, and that the AMA had a duty to show its concern for patients, but was not persuaded that this could not have been achieved in a way that was less restrictive of competition, for instance by public education campaigns.

The movement toward scientific reform[edit]

In 1978, the Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics (JMPT) was launched. Keating dates the birth of chiropractic as a science to a 1983 commentary in the Journal in which Kenneth DeBoer, an instructor at Palmer College, revealed the power of this journal to empower faculty at chiropractic schools, enabling them to challenge the status quo, to publicly address issues related to research, training and skepticism, and to raise professional standards. [17]

In Medicine, this kind of reform in journals had already come in previous decades, along with ever increasing requirements of training after medical school in order to practice. By the 1980's, board certification in a medical specialty was a requirement to join many HMOs or to launch a successful independent practice and effectively, that meant at least three or more years of training after the MD or DO degree. Physicians did not accept chiropractors as equals in terms of education and training, but the increase in the education of chiropractic and the elevation of one of their journals to peer reviewed status had, together, challenged the long-held notions that chiropractic was markedly deficient educationally and uniformly uninterested in scholarship.

Of course, the Wilk case showed that the shunning of another health care profession was not legal, whether or not physicians felt that the profession was 'scientific'. But had the promise of better health care by virtue of pure science been delivered? Physicians had always claimed that medicine was both an art and a science, but, in the USA, a focus on technology and tremendous demands on medical students for academic excellence had come at a cost, and it was the art of clinical care that appeared to pay it. In the years after the successes of the polio vaccine and penicillin, medical care continued to improve, but the popularity of physicians with the public had fallen and continued to fall. Patients complained about the impersonal nature of medicine as technology increased, and in response, medical schools began to be concerned about increasing the social skills of their students.[20] At the same time, alternative care became increasingly popular in the USA. Complementary and alternative medicine began to be acknowledged as a force in health care, and much of its effectiveness was attributed to the excellent interpersonal skills of the practitioners. Of the professions providing alternative care, in the eyes of physicians, chiropractors stood above the rest in terms of training, education, and accountability to patients.

In 1992, the AMA declared "It is ethical for a physician to associate professionally with chiropractors provided that the physician believes that such association is in the best interests of his or her patient. A physician may refer a patient for diagnostic or therapeutic services to a chiropractor permitted by law to furnish such services whenever the physician believes that this may benefit his or her patient. Physicians may also ethically teach in recognized schools of chiropractic." [21] This opened doors for members of the AMA to collaborate more openly with chiropractors in patient care as well as allowing better communication between the professions, both within their learning institutions and for general research purposes.

There are still some chiropractors who are very vocal in antivaccinationist sentiments, but how representative they are of the profession is unclear. A review in 2000 concluded that "... it is apparent that their views do not represent those of practising chiropractors in general. However, a minority of chiropractors in the USA today still publicly advocate 'drugless' care of children using chiropractic adjustments, and suggest that the risks of vaccination are high and the benefits doubtful. Several chiropractors, possibly members of the quiet majority, have felt compelled to contribute scholarly works that clearly demonstrate a provaccination stance" [22]

Efficacy[edit]

In 1978, the Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics (JMPT) was launched. Joseph Keating, a historian of chiropractic, dates the birth of chiropractic as a science to a 1983 commentary in the Journal which describes the power of this journal to enable faculty at chiropractic schools to challenge the status quo, to publicly address issues related to research, training and skepticism, and to raise professional standards.[23] By 1997, there were 14 peer-reviewed journals that specifically encouraged chiropractic research, with the JMPT indexed in Index Medicus. With some federal funding, the claims of chiropractic began to be tested by large, objective clinical trials, providing a stronger evidence base for assessing these claims.

In 1997, an AMA report discussing chiropractic stated that "manipulation has ... a reasonably good degree of efficacy in ameliorating back pain, headache, and similar musculoskeletal complaints." In 1998, The Manga Report, funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health, accepted the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of chiropractic for low-back pain, found that it had higher patient satisfaction levels, and said that "major savings from chiropractic management come from fewer and lower costs of auxiliary services, fewer hospitalizations, and a highly significant reduction in chronic problems, as well as in levels and duration of disability." Since then, several large randomized studies have confirmed that not only is manual therapy at least as good as these conventional medical treatments of back pain, but that patients tend to be more satisfied with chiropractic care and that the overall cost is similar. [24] Evidence of efficacy also comes from studies of patient satisfaction and workers' compensation cases; these suggest that most patients are very satisfied with chiropractic treatment, and for example, patients who consult a chiropractor for back-related problems are likely to lose fewer days at work than patients with similar complaints who consult physicians. [25]

There have been trials of chiropractic claims for other health benefits, but mostly these have been small and flawed in various ways, and so it is not possible to draw any definitive conclusions from them. A 2005 editorial in the JMPT proposed that greater involvement in the Cochrane Collaboration, which co-ordinates evidence-based analysis of health interventions, would be a way for chiropractic to gain better acceptance within the health sciences. [26]

Safety[edit]

No intervention is without at least theoretical risk. In spinal manipulation, serious risks include: vertebrobasilar accidents, strokes, spinal disc herniation, vertebral fracture, and cauda equina syndrome. However, the chance of such a serious risk is very low, so low that it is difficult to state an actual incidence of these events. Most commonly, in the medical and chiropractic literature, the risk of such injury occurring with spinal adjustment is estimated at one chance in a million.

A 1996 study showed that manipulation of the first two vertebra of the spine is the most risky of the adjustments, and that serious injury is particularly associated with passive rotation of the neck. However, compared to drugs, surgery or invasive interventions, spinal adjustment is in a category that may be termed "safe". Serious complications have been reported to be 1 in a million manipulations or fewer, but there is uncertainty about how these are recorded; a survey in 2002 of neurologists in the UK concluded that underreporting rendered estimates 'nonsensical'.[27]

Few studies of stroke and cervical manipulation take account of the differences between 'manipulation' and the 'chiropractic adjustment'. According to a report in the JMPT, manipulations administered by a Kung Fu practitioner, general practitioners, osteopaths, physiotherapists, a wife, a blind masseur, and an Indian barber had all been incorrectly attributed to chiropractors.[28]

However, in 2002, the national health service of Canada suspended pediatric care by chiropractic from financial support after media attention to a small number of cases of stroke occurring either immediately, or soon, after spinal adjustment. Although these cases were few, they were clustered in time, and the consequences of the strokes were devastating. The cases in adults were almost certainly not due to the chiropractic treatment, despite what was seen by family members as an obvious relationship, and investigation by Canadian health authorities proved reassuring to the public. However, exhaustive review established that there is a tiny, but real, risk of serious harm with chiropractic adjustment. That miniscule risk comes from the chance of inciting arterial dissection in the blood vessels in the neck that supply oxygen and nutrients to the brain. This is such a small risk that adjustments cannot be termed "unsafe", instead, a different issue was raised. In health care, the risk of a procedure is compared to its benefit over doing either nothing or doing a 'placebo' intervention that has no risk. In routine pediatric care, the relative risk was too high to be acceptable to the reviewing experts. As there is no evidence that chiropractic care of children for such common conditions as otitis media and excessive crying is more effective than placebo or watchful waiting, the Council concluded that even the miniscule risk of stroke cannot be condoned.

Critical views of Chiropractic[edit]

- See Critical views of Chiropractic for a detailed account.

In its 100-year history, chiropractic has been under frequent attack from osteopathy, from conventional medicine, from scientists critical of its scientific foundations, and recently from web-based critics of its advertising tactics and of the extravagant claims and dubious practices of some chiropractors. Although the profession has survived, and indeed thrived, the profession itself has voiced many of these same criticisms in a move to reform chiropractic from within. Nevertheless, at present, although many family physicians in the USA are willing to refer their patients to chiropractors, chiropractic is not integrated into hospital-based medicine. Most licensed physicians and academic scientists remain skeptical about the scientific foundations of chiropractic as well as its efficacy for conditions other than some directly associated with the spine, and some are concerned that some chiropractors may not recognise serious medical conditions that affect some of their patients. Those physicians that are disturbed by chiropractic treatment do not argue that the treatment itself is unsafe, but that its provision may result in the delay of the recognition and medical treatment of underlying medical conditions.[29] There is particular concern that some chiropractors still regard their adjustments as the "cure-alls" that BJ Palmer claimed; and may encourage patients that vaccination, medicines, and surgery are all better avoided - as did the "old school" chiropractic practitioners.

This concern is to some extent mirrored by chiropractors who believe that their training and experience makes them better able to diagnose and treat a certain set of musculoskeletal problems than conventional physicians. The quality of undergraduate medical education in musculoskeletal pain has also been criticised by the medical profession itself; a recent review claimed that "...patients with musculoskeletal complaints are often ignored, their problems underestimated by doctors and, consequently, they do not have timely access to effective treatments. This reflects the common belief that we have to learn to live with musculoskeletal pain and disability as nothing can be done. It also reflects the inadequate education and training of doctors that begins at medical school." [30]

See also[edit]

- Chiropractic history

- Spinal adjustment

- Spinal manipulation

- Vertebral subluxation

- Chiropractic education

- Council on Chiropractic Education

- Federation of Chiropractic Licensing Boards

- Critical views of Chiropractic

References[edit]

- ↑

The chiropractic subluxation

- 'Subluxation Degeneration',from echiropractic, online educational site

- 'The vertebral subluxation complex' from The Chiropractic Resource Organization [1]

- 'Subluxation degeneration' from The Kansas Chiropractic Foundation [2]

- Hartman RL (1995) Spinal nerve chart of possible effects of vertebral subluxations

- ↑ Subluxation and innate intelligence

- Black D (1990) 'Inner Wisdom: The Challenge of Contextual Healing'Chapter II, Chiropractic Belief Systems

- McDonald W (2003) How Chiropractors Think and Practice: The Survey of North American Chiropractors. Institute for Social Research, Ohio Northern University See here for a review

- Seaman D, Winterstein J (1998). "Dysafferentation: a novel term to describe the neuropathophysiological effects of joint complex dysfunction". JMPT 21: 267-80. PMID 9608382.

- ↑ The chiropractic profession

- Accredited chiropractic degree Programs

- Association of Chiropractic Colleges, Chiropractic Paradigm

- 'The Chiropractic Profession and Its Research and Education Programs' Report to Florida State University (2000)

- Vickers A, Zollman C (1999). "ABC of complementary medicine. The manipulative therapies: osteopathy and chiropractic". BMJ 319: 1176-9. PMID 10541511.

- The Council on Chiropractic Education Standards for Doctor of Chiropractic Programs and Requirements for Institutional Status

- Cooper RA, McKee HJ (2003). "Chiropractic in the United States: trends and issues". Milbank Q 81: 107-38. PMID 12669653.

- ↑ Mootz RD. Cherkin DC. Odegard CE. Eisenberg DM. Barassi JP. Deyo RA. Characteristics of chiropractic practitioners, patients, and encounters in Massachusetts and Arizona. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics. 28(9):645-53, 2005 UI: 16326233

- ↑ Chiropractic in practice

- Chiropractic and cancer in the UK.

- A visit to the chiropractor

- A hand held percussion instrument

- Thompson technique table

- Cox Flexion/Distraction table

- ↑ Morgan L (1998). "Innate intelligence: its origins and problems". J Can Chir Ass 42: 35-41.

- ↑ Gatterman MI (1988) Foundations of the Chiropractic Subluxation

- ↑ Rosner A (2006) Occam's razor and subluxation: a close shave. Dynamic Chiropractic24:(18)

- ↑ Healey JW (1990) It's Where You Put the Period Dynamic Chiropractic, 8 (21)

- ↑ Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education: Position Paper One: What is Objective Straight Chiropractic? and Position Paper Five: Referral

- ↑ The General Chiropractic Council states "It is against the law for someone who is not registered with us to make you think that they are a chiropractor."

- ↑ (From Vol. 2, "History of Davenport and Scott County" by Harry E. Downer - S. J. Clarke Publishing Co. 1910 Chicago, [3])

- ↑ Colgrove J (2005) "Science in a democracy": the contested status of vaccination in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Isis 96:167-91

- ↑ :Phillips R (1998) Education and the chiropractic profession Dynamic Chiropractic

- ↑ :The Neurocalometer [4]

- Chiropractic history Archives Neurocalometer

- ↑ Cherkin D et al (1989) Family physicians' views of chiropractors: hostile or hospitable? Am J Public Health. 79:636–7 [5]

- ↑ Campbell JB et al' (2000) Chiropractors and Vaccination: A Historical Perspective. Pediatrics 105:e43

- ↑ :Homola S (2006) Can Chiropractors and Evidence-Based Manual Therapists Work Together? An Opinion From a Veteran Chiropractor:Keating J (1990) A Guest Review Dynamic Chiropractic

- ↑ The Wilk case: text of the Judge's opinion and order

- ↑ Gracey CF et al. (2005) Precepting humanism: strategies for fostering the human dimensions of care in ambulatory settings. Academic Medicine. 80:21-8

- Kern DE et al. (2005) General Internal Medicine Generalist Educational Leadership Group. Teaching the psychosocial aspects of care in the clinical setting: practical recommendations. Academic Medicine. 80:8-20

- ↑ AMA code of Ethics: E-3.041 Chiropractic (March, 1992)

- ↑ Campbell JB et al. (2000) Chiropractors and vaccination: a historical perspective. Pediatrics 105: e43

- ↑ Keating J (1997) Faulty logic and nonskeptical arguments in chiropractic. Skeptical Inquirer 21

- ↑ Efficacy

- Hurwitz E et al (2006). "A randomized trial of chiropractic and medical care for patients with low back pain: eighteen-month follow-up outcomes from the UCLA low back pain study". Spine 31: 611-21; discussion 622. PMID 16540862.

- Hurwitz EL et al (2005). "Satisfaction as a predictor of clinical outcomes among chiropractic and medical patients enrolled in the UCLA low back pain study". Spine 30: 2121-8. PMID 16205336.

- Skargren EI et al (1998). "One-year follow-up comparison of the cost and effectiveness of chiropractic and physiotherapy as primary management for back pain. Subgroup analysis, recurrence, and additional health care utilization". Spine 23: 1875-83; discussion 1884. PMID 9762745.

- Manga P, Angus D (1998) Enhanced Chiropractic Coverage Under OHIP as a Means of Reducing Health Care Costs, Attaining Better Health Outcomes and Achieving Equitable Access to Health Services. The Manga Report

- McCrory DC et al (2001) Evidence Report

- Behavioral and Physical Treatments for Tension-type and Cervicogenic Headache FCER Research Central

- Ernst E (2006). "A systematic review of systematic reviews of spinal manipulation". J R Soc Med 99: 192-6.

- Balon J (1998). "A comparison of active and simulated chiropractic manipulation as adjunctive treatment for childhood asthma". New Eng J Med 339: 1013-20. PMID 9761802.

- ↑ Compensation studies

- Wolk S (1988). "An analysis of Florida workers' compensation medical claims for back-related injuries". J Amer Chir Ass 27: 50-9.

- Nyiendo J et al (2001). "Pain, disability, and satisfaction outcomes and predictors of outcomes: a practice-based study of chronic low back pain patients attending primary care and chiropractic physicians". JMPT 24: 43-9. PMID 11562650.

- Johnson M et al (1989). "A comparison of chiropractic, medical and osteopathic care for work-related sprains and strains". JMPT 12: 335-44. PMID 2532676.

- Cherkin CD et al (1988). "Managing low back pain. A comparison of the beliefs and behaviours of family physicians and chiropractors". West J Med 149: 475-80.

- House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology Report on CAMs [9]

- ↑ Cochrane Reports

- French S, Green S. "The Cochrane Collaboration: is it relevant for doctors of chiropractic?". JMPT 28: 641-2. PMID 16326231.

- Cochrane collaboration reports on asthma, carpal tunnel syndrome, painful menstrual periodsand migraine.

- ↑ CMAJ journal survey

- ↑ Safety

- NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (2000) Report on acute and chronic low back pain

- Klougart N et al (1996). "Safety in chiropractic practice, Part I; The occurrence of cerebrovascular accidents after manipulation to the neck in Denmark from 1978-1988". JMPT 19: 371-7. PMID 8864967.

- [10]

- Ernst E (2002). "Spinal manipulation: its safety is uncertain". CMAJ 166: 40-1. PMID 11800245.

- Lauretti W What are the risk of chiropractic neck treatments?

- NHS Evaluation of the evidence base for the adverse effects of spinal manipulation by chiropractors

- Coulter ID et al (1996) 1996 study 'The appropriateness of manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine' Rand Monograph Report (RAND MR-781-CCR) ISBN 0-8330-2420-5 [11]

- ↑ Report 12 of the AMA Council on Scientific Affairs on "Alternative Medicine" (A-97), published in 1998, reflecting literature to June 1997

- ↑ Woolf AD et al. (2004) Global core recommendations for a musculoskeletal undergraduate curriculum. Ann Rheum Dis 63:517-524 PMID 15082481

KSF

KSF