Coagulation

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

Coagulation is "the process of the interaction of blood coagulation factors that results in an insoluble fibrin clot."[1]

Coagulation, along with platelet activation, leads to hemostasis.

Biochemistry[edit]

| Pathway | Diagnostic test | Blood coagulation factor | Half-life | Abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | Partial thromboplastin time (PTT) |

Factor VIII (Antihemophilic factor) | ||

| Factor IX | 24 hours[2] | Liver failure, heparin, warfarin therapy, Vitamin K deficiency | ||

| Factor X | 40 hours[2] | Liver failure, heparin, warfarin therapy, Vitamin K deficiency | ||

| Factor XI | Liver failure | |||

| Factor XII | Liver failure | |||

| Extrinsic | Prothrombin time (PT) |

Factor VII (Proconvertin; Stable factor) | 5-7 hours[2] | Liver failure, warfarin therapy, Vitamin K deficiency |

| Factor X | 40 hours[2] | Liver failure | ||

| Final Common Pathway | PT & PTT | Factor I (fibrinogen) | Liver failure | |

| Factor II (prothrombin) | 3 days[2] | Liver failure, warfarin therapy, Vitamin K deficiency | ||

| Notes: Factor X is a member of both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways and, as with abnormalities of the final common pathway, affects both the partial thromboplastin time and the prothrombin time | ||||

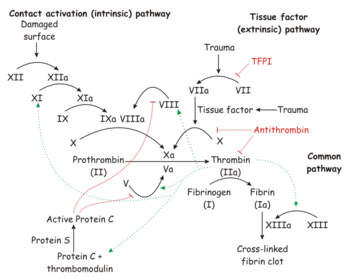

Details and figures depicting the coagulation pathways are available online at the National Library of Medicine.[3]

Production of coagulation factors[edit]

All coagulation factors are produced in the liver except for von Willebrand's factor which is made in blood vessels and the spleen.[4]

The synthesis of coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X and proteins C and S is dependent on vitamin K.[5] The half-lives of the cofactors range from five to seven hours for factor VII to 3 days for factor II (prothrombin).

Disorders of coagulation[edit]

Blood coagulation disorders are "hemorrhagic and thrombotic disorders that occur as a consequence of abnormalities in blood coagulation due to a variety of factors such as coagulation protein disorders; blood platelet disorders; blood protein disorders or nutritional conditions."[6]

Factor I deficiency[edit]

Deficiency of Factor I (fibrinogen) may be inherited (afibrinogenemia) or acquired.

Factor II deficiency[edit]

Deficiency of Factor II (prothrombin) leads to hypoprothrombinemia. The defiency may be acquired in due to prothrombin antibodies.[7]

Factor V deficiency[edit]

Factor V deficiency is a "(known as proaccelerin or accelerator globulin or labile factor) leading to a rare hemorrhagic tendency known as Owren's disease or parahemophilia. It varies greatly in severity. Factor V deficiency is an autosomal recessive trait."[8]

Factor VIII deficiency[edit]

Hemophilia, an usually genetic deficiency of certain factors necessary for coagulation, is of two major types:[9]

- Hemophilia A (HA), the most common form, involving Factor VIII (FVIII) deficiency

- Hemophilia B (HB), also called Christmas disease, due to a deficiency of Factor IX (FIX)

- Acquired hemophilia, an autoimmune disease that targets Factor VIII

Factor X deficiency[edit]

Factor X deficiency is a "blood coagulation disorder usually inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, though it can be acquired. It is characterized by defective activity in both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, impaired thromboplastin time, and impaired prothrombin consumption."[10]

Multiple factor deficiencies[edit]

Multiple factor deficiencies may be present in disease, or produced deliberately in treating diseases of the coagulation system.

Cirrhosis[edit]

Liver failure and cirrhosis affects all coagulation factors except von Willebrand's factor and Factor VIII.[4][5]

Surprisingly, patients with liver failure are not at reduced risk of embolism and thrombosis. The risk of thrombosis and embolism among patients with liver failure correlates with the partial thromboplastin time and not the International Normalized Ratio.[5] Fatal pulmonary embolism has been reported, and may be due to reduction in synthesis by the liver of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III and compared to reduction in coagulation factors.[11]

Disseminated intravascular coagulation[edit]

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) affects all coagulation factors.

[edit]

Preventing inappropriate coagulation[edit]

Anticoagulants are medications use to prevent coagulation and embolism and thrombosis.

Heparin therapy[edit]

Heparin therapy primarily affects Factors IX and X of the intrinsic pathway.

The effect of heparin is monitored by the partial thromboplastin time. However, it can affect the prothrombin time as well.[12] and extend the prothrombin time by one to two seconds.[13]

Warfarin therapy[edit]

Warfarin therapy reduces the vitamin K dependent cofactors II, VII, IX, and X and the vitamin K dependent Protein C. The level of factor II is thought to most influence coagulation.[2][14] The levels of factor VII and Protein C fall the fastest after warfarin is started.[14] With the exception of Factor IX, these factors are from either the extrinsic pathway or the final common pathway.

The effect of warfarin is measured by the prothrombin time (or the International Normalized Ratio derived from the prothrombin time) although warfarin can also affect the partial thromboplastin time.[15][16]

Reversing inappropriate coagulation[edit]

Thrombolytic drugs are used to dissolve harmful clots caused either by a disorder of coagulation, or of an internal traumatic event, such as a myocardial infarction, where a clot is blocking necessary blood flow. They are proteins, produced by recombinant DNA technologies, or extracted from bacterial or human cell cultures.

Most cause the proenzyme, plasminogen, presented in plasma, to the active enzyme plasmin. Plasmin then dissolves fibrin and inactivates other proteins involved in coagulation, principally fibrinogen. The main tbrombolytics used in clinical practice are urokinase, streptokinase, or one of several forms of tissue plasminogen activator (TPA). The TPA variants include alteplase, Reteplase, and tenecteplase.

While thrombolysis can be extremely effective, truly modifying and reversing the disease process, they are absolutely contraindicated in an actively bleeding patient, and have relative contraindications in patients at high risk of hemorrhage. Indications for thrombolyis include:

In stroke, for example, it is utterly essential that the cause is confirmed to be ischemia rather than hemorrhage. Making this distinction often requires cerebral angiography.

Treating inadequate coagulation[edit]

Hemophilia[edit]

Synthetic FVIII and FIX are available, and can be used for prophylaxis and treatment of acute hemorrhage. Other drugs can counter the inhibition in acquired hemophilia, or help accelerate coagulation in acute hemorrhage.

von Willebrand's disease[edit]

Factor XI Deficiency[edit]

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Anonymous. Blood coagulation. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved on 2008-01-10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Eckhoff CD, Didomenico RJ, Shapiro NL (2004). "Initiating warfarin therapy: 5 mg versus 10 mg". Ann Pharmacother 38 (12): 2115–21. DOI:10.1345/aph.1E083. PMID 15522981. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer Berg Tymoczko; Stryer, Lubert; Berg, Jeremy Mark (2002). Biochemistry. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-7167-4955-6. Figure of coagulation pathways

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sallah S, Bobzien W (1999). "Bleeding problems in patients with liver disease. Ways to manage the many hepatic effects on coagulation". Postgrad Med 106 (4): 187–90, 193–5. PMID 10533518. [e]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mammen EF (1992). "Coagulation abnormalities in liver disease". Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 6 (6): 1247–57. PMID 1333467. [e]

- ↑ Anonymous. Blood Coagulation Disorders. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Bajaj SP, Rapaport SI, Fierer DS, Herbst KD, Schwartz DB (1983). "A mechanism for the hypoprothrombinemia of the acquired hypoprothrombinemia-lupus anticoagulant syndrome". Blood 61 (4): 684–92. PMID 6403077. [e]

- ↑ Anonymous. Factor V Deficiency. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Agaliotis DP, Zaiden RA, Ozturk,S (2 January 2008), "Hemophilia, Overview", eMedicine

- ↑ Anonymous. Factor X Deficiency. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Espiritu JD (2000). "Pulmonary embolism in a patient with coagulopathy from end-stage liver disease.". Chest 117 (3): 924-5. PMID 10713038.

- ↑ Schultz NJ, Slaker RA, Rosborough TK (1991). "The influence of heparin on the prothrombin time". Pharmacotherapy 11 (4): 312–6. PMID 1923913. [e]

- ↑ Lutomski DM, Djuric PE, Draeger RW (1987). "Warfarin therapy. The effect of heparin on prothrombin times". Arch. Intern. Med. 147 (3): 432–3. PMID 3827418. [e]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Harrison L, Johnston M, Massicotte MP, Crowther M, Moffat K, Hirsh J (1997). "Comparison of 5-mg and 10-mg loading doses in initiation of warfarin therapy". Ann. Intern. Med. 126 (2): 133–6. PMID 9005747. [e]

- ↑ Bell DF, Harris WH, Kuter DJ, Wessinger SJ (1988). "Elevated partial thromboplastin time as an indicator of hemorrhagic risk in postoperative patients on warfarin prophylaxis". J Arthroplasty 3 (2): 181–4. PMID 3397749. [e]

- ↑ Hauser VM, Rozek SL (1986). "Effect of warfarin on the activated partial thromboplastin time". Drug Intell Clin Pharm 20 (12): 964–7. PMID 3816546. [e]

KSF

KSF