Counterinsurgency

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

Counterinsurgency involves the concepts and actions taken to defeat an insurgency. Insurgency can be described generally as the action of a group that wants to replace a government by means considered illegal by that government. Counterterrorism overlaps counterinsurgency, but they are not identical. Counterterrorism is enemy-centric, intended to destroy terrorists and their support networks, or convince terrorists to stop their activities, perhaps by societal reintegration. Counterinsurgency is population-centric, protecting civilians from terrorists, convincing them to stop supporting terrorists, and to provide them services that the terrorists may provide.

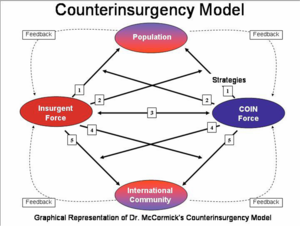

To counter an insurgency, one first must understand the models and dynamics of insurgency. McCormick’s model, for example, [1] is designed as a tool for counterinsurgency (COIN), but develops a symmetrical view of the required actions for both the Insurgent and COIN forces to achieve success. In this way the counterinsurgency model can demonstrate how both the insurgent and COIN forces succeed or fail. The model’s strategies and principle apply to both forces, therefore the degree the forces follow the model should have a direct correlation to the success or failure of either the Insurgent or COIN force.

The model depicts four key elements or players:

- Insurgent Force

- Counterinsurgency force (i.e., the government)

- Population

- International community.

All of these interact, and the different elements have to assess their best options in a set of actions:

- Gaining Support of the Population

- Disrupt Opponent’s Control Over the Population

- Direct Action Against Opponent

- Disrupt Opponent’s Relations with the International Community

- Establish Relationships with the International Community

Counterinsurgency resources[edit]

Transgovernmental and nongovernmental organizations[edit]

Friendly nations and alliances[edit]

The United States, and even NATO, cannot control all insurgencies. Fortunately, regional powers such as Nigeria and Brazil, as well as organizations such as the African Union (AU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), have shown an increased willingness to take some responsibility for containing turmoil in their regions. Consider, for example, the deployment of AU troops in the Darfur region of Sudan and ECOMOG in Sierra Leone. But as Darfur has also demonstrated, regional troops can mobilize only if they have adequate logistical and transport capabilities", provided by US airlift to Darfur[2] and UK in Sierra Leone (i.e., Operation Barras). See Foreign internal defense for U.S.-specific counterinsurgency doctrine.

Actions[edit]

Create popular support[edit]

The Taliban came to prominence when it interfered with warlord and bandit attacks on civilians; Mullah Omar is generally said to have come to prominence by stopping the rapes of Afghan children. [3] Hizbollah provided social services that the Lebanese government could not.[4] Creating popular support begins with security, but also often extends to providing infrastructure services.

Another dimension of creating support is that the government needs to be visible, and credibly interested in the population. Limited external support helped Ramon Magsaysay defeat the Hukbalahap insurgency in the Philippines, with one of the most important parts of that support being the availability of air transport so he could be visible in remote areas.[5] When Magsaysay visited a remote village and saw it needed a water well, engineers arrived within a reasonable time after he was there, implying cause and effect. Anticorruption efforts are key.

Disrupt the insurgents' control of people and resources[edit]

This is the population-centric aspect, which takes place on multiple levels. One key factor is getting security forces close to the people, so they can both patrol efficiently and react quickly. This does not mean putting troops into static defensive posts, especially those small and remote enough that the insurgents can take them at will, and regard them as sources of supply, as in the Indochinese revolution.[6]

David Kilcullen, visiting the 1/325 Airborne battalion, during the "Surge" in Baghdad was told they had reduced their casualties since the start of 2007, because they were vulnerable to ambushes and IEDs while "commuting to the fight". When, for example, they were based in a police station, they could react to problems immediately, but also make it harder to infiltrate the Sunni areas in which the security forces were concentrated. [7]

Take direct action against insurgents[edit]

This must be applied delicately; too forceful action, which results in significant civilian casualties, can build support for the insurgency. Al-Qaeda's doctrinal documents emphasize provocation to encourage overreaction, but this is not unique to them. The Latin American Marxist, Carlos Marighella, wrote extensively about inciting overreaction, specifically aiming at the security gap.[8]

Cut off international/external support for insurgents[edit]

In many insurgencies, the insurgents depend on sanctuary in an outside country, or the provision of supplies, information and advisors, and even combat resources from other countries.

Build international support for the counterinsurgents[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ McCormick, Gordon. "The Shining Path and Peruvian terrorism". RAND Corporation.

- ↑ "U.S. Airlift AU Troops to Darfur", Sudan Vision, 30 October 2004

- ↑ Robert Marquand (October 10, 2001), "The reclusive ruler who runs the Taliban", Christian Science Monitor

- ↑ Ken Silverstein (March 2007), "Augustus Norton on Hezbollah’s Social Services", Harper's Magazine

- ↑ Sagraves, Robert D (April 2005), The Indirect Approach: the role of Aviation Foreign Internal Defense in Combating Terrorism in Weak and Failing States, Air Command and Staff College

- ↑ Fall, Bernard B. (1964), Street without joy: insurgency in Indochina, 1946-63 (3rd ed.), Literature House (China)

- ↑ David Kilcullen (2009), The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195368345, pp. 141-143

- ↑ Marighella, Carlos. Minimanual of the Urban Guerrilla.

KSF

KSF