Crude oil desalter

From Citizendium - Reading time: 6 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 6 min

A crude oil desalter is a device used in petroleum refineries to remove inorganic salts, water and sediment from the incoming petroleum crude oil feedstock before it is refined. This article focuses on the use of electrostatic desalters to produce a dehydrated, desalted crude oil with a low sediment content.[1][2][3][4] Almost all refineries now use electrostatic desalters. However, there may still be a few refineries employing the older, less efficient method that utilizes chemicals and settling tanks.

Removal of the salts, water and sediment is necessary to avoid excessive fouling of equipment as well as corrosion from the generation of hydrochloric acid (HCl) by the hydrolysis of the chloride salts present in the incoming crude oil, in particular magnesium chloride (MgCl2) and calcium chloride (CaCl2). Any salts that are not removed represent a source of metals that can "poison"[5] expensive catalysts used in various petroleum refinery processes.[1][2][3].

Contaminants in crude oil as received by refineries[edit]

The amount of water, salts and sediment in the crude oil as received at petroleum refineries varies widely with the source of the crude oil, the prior processing of the crude oil at the source sites and with the mode of transporting the crude oil from its source to the refineries.

Typically, the raw crude oil produced by oil wells drilled into underground petroleum oil reservoirs is accompanied by brine (i.e., water containing inorganic chloride salts). The amount of chloride salts in the brine may be as high as 20 % by weight. Some of that brine is emulsified with the crude oil. The salts present in raw crude oil may be in the form of crystals dispersed in the oil and some of the salts are dissolved in the brine in their ionized form.

The salts present in petroleum crude oils are mainly chlorides with following approximate breakdown:

- 75 weight percent Sodium chloride ( NaCl )

- 15 weight percent Magnesium chloride ( MgCl2 )

- 10 weight percent Calcium chloride ( CaCl2 )

The sediment present in petroleum crude oils include clay, rust, iron sulfide ( FeS ), asphaltenes and various other water-insoluble particles.

The raw crude is usually subjected to processing at or very near to the oil field production sites in order to separate the oil from the brine before the oil is transported to petroleum refineries via pipeline, railway tank cars, tanker trucks or sea-going crude oil tankers. Such oilfield processing typically involves washing the oil with water to remove salts, some heating, use of demulsifying chemicals and simple settling vessels and tanks. In some cases, the oilfield processing includes electrostatic desalting as well. In general, the oilfield processing facilities strive to remove enough water, sediment and salts so that the transported crude oil contains less that 1 to 2 % by volume of sediment and water ( BS&W ) and less than 10 to 20 pounds of salts per 1000 barrels ( PTB ) of clean, water-free crude oil (which is equivalent to a salt content of 34 to 68 ppm by weight).[6] Nevertheless, the crude oils as received at petroleum refineries have a salt content that ranges from a PTB of 10 to 300 (34 to 1,020 ppm by weight), based on spot samples of many different crude oils as delivered to refineries.[1][7] Transportation by sea-going crude oil tankers is vulnerable to salt water pickup by the crude oil cargo.

Crude oil also contains trace elements such as vanadium ( V ), nickel ( Ni ), copper ( Cu ), cadmium ( Cd ), lead ( Pb ) and arsenic ( As ), all of which can cause problems in some of the various processing units in the petroleum refineries. They may be present in the form of oil-soluble organo-metallic compounds or as water-soluble salts.

Description of petroleum refinery electrostatic desalters[edit]

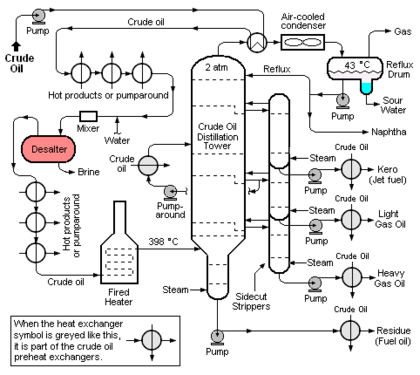

The crude oil distillation unit (CDU) is the first processing unit in virtually all petroleum refineries. The CDU distills the incoming crude oil into various fractions of different boiling ranges, each of which are then processed further in the other refinery processing units. Figure 1 below is a schematic flow diagram of a typical CDU and, as can be seen, the desalter (colored red for clarity) is typically installed in the heat exchange train that heats the incoming crude oil before it flows through a fired heater and into the distillation tower. The desalter is usually located at the point where the incoming crude oil has been heated to about 100 to 150 °C. The optimum desalter temperature varies somewhat with the crude oil source.[1]

At that point, wash water is injected and mixed into the continuous flow of crude oil and the resulting oil-water emulsion then continuously enters the electrostatic desalter. The rate of wash water required is about 4 to 10 % by volume of the crude oil rate. The optimum wash water rate varies with the API gravity[8] of the crude oil and with the desalter temperature.[1]

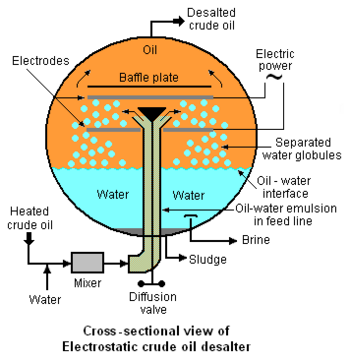

Externally viewed, the typical electrostatic desalter is a horizontal, cylindrical vessel as depicted in Figure 1. A cross-sectional end-view of the of the desalter's interior is shown in Figure 2 below. The oil-water emulsion that enters from the bottom of the desalter through the feed line is a thorough mixture of two non-miscible liquids consisting of a continuous phase (the crude oil) and a dispersed phase (water in the form of very small droplets with dimensions ranging from 1 to 10 micrometres). Asphaltenes and finely divided sediment solids are adsorbed on the oil-water interface and stabilize the emulsion. Thus the degree of difficulty involved in coalescing the droplets into large globules which can be settled and removed is related to the presence of asphaltenes, sediments and other water-insoluble contaminants.

An electrical system connected to the electrodes within the desalter (see Figure 2) generates an electrostatic field at potentials ranging from about 6,000 volts to about 20,000 volts that induce dipole attractive forces between neighboring droplets of water. In other words, the electrostatic field results in each droplet having a positive charge on one side and a negative charge on the other which cause the droplets to coalesce because of the attractive force generated by the opposite charges on neighboring droplets. The resulting larger water droplets (globules), along with water-insoluble solids, then settle to the bottom of the desalter. The settled water is continuously withdrawn from the desalter from a point somewhat above the desalter bottom (see Figure 2) and is referred to as a brine because it contains the inorganic salts that originally entered the desalter with the water in the crude oil. The settled sediment at the bottom of desalter is withdrawn as a sludge at intermittent intervals as needed to prevent solids from entering the settled water withdrawal outlet.

The desalter depicted in Figure 2 and described above is referred to as a single-stage desalter and represents but one of many available configurations, including configurations such as:

- Flowing the crude oil through two stages in series and recycling part of the brine from the second stage for use as wash water to the first stage.

- Flowing the crude oil through two stages in series with no recycle of brine from the second stage.

- Using multiple electrostatic fields in a single vessel so as to create, in effect, two or three stages of desalting within that single vessel.

Desalter wash water[edit]

Many of the refining processes in a petroleum refinery produce wastewater streams (commonly referred to as sour waters) which contain dissolved hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and ammonia (NH3) gases in the form ionic ammonium hydrosulfide (NH4HS). Usually, refineries collect all of their sour waters and use steam distillation towers (called sour water strippers) to strip virtually all of the hydrogen sulfide and somewhat less of the ammonia from aggregated sour waters.[3] The striped sour water is then recycled for reuse as desalter wash water, augmented by fresh water if needed.

Some of the refinery sour water streams contain also contain phenols[9] which are not easily stripped out. Thus, the stripped sour water used as desalter wash water contains phenols which are preferentially absorbed by the crude oil and will subsequently become part of the naphtha and kerosene fractions distilled from the crude oil (see Figure 1).

Desalter performance[edit]

When a desalter has been well-designed and well-operated, it will achieve an average of 85 to 95% removal of inorganic salts from the crude oil and the water content of the desalted crude oil will be less than 0.2 volume percent of the crude oil.[1]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Jean-Pierre Wauquier (Editor) (2000). Petroleum Refining, Volume 2, Separation Processes. Editions Technip. ISBN 2-7108-0761-0. Limited preview in Google Books

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Francis S. Manning and Richard E. Thompson (1995). Oilfield Processing, Volume 2: Crude oil. Pennwell Books. ISBN 0-87814-354-8. Limited preview in Google Books

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants. John Wiley & Sons. Library of Congress Control Number 67019834.

- ↑ Petroleum Wastewater – A Case Study Greg Johnson (from Water and Wastewater.com)

- ↑ Note: Irreversible deactivation of catalysts.

- ↑ Note: In the United States, the amount of inorganic salts in a crude oil is expressed as pounds per thousand barrels and abbreviated as PTB. Based on a crude oil having an API gravity of 34 °API (which is equivalent to having a specific gravity of 0.8550), 1 PTB of salt = 3.4 ppm of salt by weight = 2.85 mg of salt per litre of crude oil.

Also, the amount of sediment and water present in a crude oil is expressed as % by volume of BS&W (Basic Sediment and Water) as measured by American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Standards D96, D4006, D4007 or Institute of Petroleum (IP) Test Method 386. - ↑ H.K. Abdel-Aal, Mohamed Aggaour and M.A. Fahim (2003). Petroleum and Gas Field Processing. CRC Press. ISBN 0-8247-0962-4. Limited preview in Google Books

- ↑ Note: API gravity = °API = (141.5 / SG) – 131.5 where SG = specific gravity 60°F/60°F = (density of oil at 60 °F) / (density of water at 60 °F) and 60 °F = 15.56 °C

- ↑ Note: The refining industry uses the word phenols to include phenol (C 6H 5OH), the three cresols (C 7H 7OH) and the six xylenols (C 8H 9OH)

KSF

KSF