Falkland Islands

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

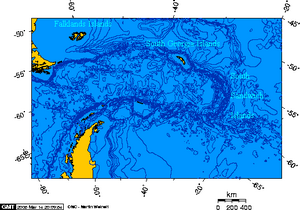

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the southern Atlantic Ocean, comprising over 200 islands including the main ones of East and West Falkland, between South America about 300 miles (500km) to the west and the South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands about 870 miles (1400km) to the east; Antarctica lies about 740 miles (1200km) south. They comprise over 200 islands, including the main ones of East and West Falkland. The islands are a British Overseas Territory with Stanley the capital but are claimed by Argentina; in Spanish, they are referred to as the Islas Malvinas.

Status[edit]

As with other British Overseas Territories, the Falkland Islands exist under the sovereignty of the United Kingdom but are not actually part of that country: the UK is responsible for defence and foreign policy, and has bestowed British citizenship on most residents of the Territories, but has not incorporated them into its own political system. For example, Falkland Islanders are not represented in the Parliament of the United Kingdom and in many respects are self-governing. They do, however, share the same Head of State (Queen Elizabeth II since 1952). The islands have seen continuous British residence since the 1830s, and there was a small British settlement on West Falkland in the 1770s.

Territorial dispute[edit]

The Falkland Islands are subject to a territorial dispute between the UK and Argentina, which led to the Falklands War in 1982. Argentina, at the time under the military junta of General Leopoldo Galtieri, invaded the Falklands and South Georgia in April of that year. The UK under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher responded militarily, and Argentina withdrew following a conflict that cost 907 lives on both sides. Since then, the UK has maintained the territory pending any change through self-determination,[1] while Argentina has continued to claim it due to various historical events and its proximity to the South American continent.[2]

Demography[edit]

The islands were home to 2,932 residents in 2012, of which 59% identified as 'Falkland Islander' and 29% as 'British'. Just over 10% of residents came from Saint Helena. Census data also showed that the Chilean population was over 6% and increasing.[3] Over 60 nationalities are represented, though most are of British descent.[4]

Economy[edit]

The islands' economy is based on fishing, sheep farming and tourism. Road, ferries and domestic airports connect communities. Substantial oil reserves exist around the islands as well.[5] The islands are also home to penguin colonies, which are a popular tourist draw.

History[edit]

European discovery[edit]

The islands appear to have never sustained any indigenous peoples. They appear on a Portuguese map of 1522, and the first recorded sighting occurred in 1592, by the English explorer John Davis. They were also visited by the Dutch in 1600. The first recorded landfall did not occur until a century later, when Captain John Strong, another Englishman, visited the islands. He named the waters between the main islands Falkland Channel after the patron of his voyage, the Viscount of Falkland. Ultimately, the name would grow from Falkland Sound to be used to refer to all the islands.

Early settlements[edit]

Though already visited by the English and Dutch, the islands were first occupied by the French, who set up a colony in 1764. Louis-Antoine de Bougainville named the islands the Malouines, and its main port St. Louis. The following year, the British landed on the western island and claimed the archipelago in its entirety, apparently unaware of the French settlement in the east.[6] In 1767, the French made an agreement with the Spanish Empire that saw its colony transferred; the Spanish translated the islands' French name as the Malvinas, and the main settlement became Puerto Soledad. The Spanish claim originated in the 1494 Treaty of Torsedillas and the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, neither of which mentioned the islands.

In 1770, the Spanish garrison expelled the British at Port Egmont in the west, but an agreement which left sovereignty unresolved allowed them to return in 1771, with all sides keen to avoid a lengthy war. The British then maintained their own garrison until 1774, when the need for troops particularly in North America as the American Revolution broke out meant that it had to be abandoned. The British did, however, maintain their claim on the territory. The Spanish remained on the eastern side and developed their settlement as a penal colony, but abandoned it in 1811 as revolution broke out in South America, while maintaining their claim just as the British had done.

Origins of the territorial dispute[edit]

In 1816, Spanish colonies in South America declared independence. The nation of Argentina, at that time internationally unrecognised and part of the new United Provinces of South America, asserted that it took over all territorial claims of Spain - an action disputed by Spain, which did not recognise Argentina until 1857 (whereas the US did so in 1823,[7] and the UK in 1825[8]). Privateers made for territory in the name of the United Provinces, including Colonel Daniel Jewett, an American, who claimed the Falklands in 1820 but swiftly returned to Buenos Aires.

The next settlement was established in 1826 by the naturalised Franco-German Argentinian Luis Vernet, as part of the settlement of a debt owed by the United Provinces and with the permission of Britain.[9] Vernet's settlement became viable by 1828, just as the United Provinces were breaking up, with Argentina coming to make various territorial claims in South America and on the Falklands. It did so by appointing Vernet its unpaid Commander, sparking a protest from Britain.[10] In 1831, Vernet's settlers were expelled from the islands by the Americans, who had become involved in disputes over hunting and fishing rights, and who, according to contemporary accounts, destroyed the settlement at St. Louis. In 1832, Argentina attempted to establish another garrison and penal colony, in which law and order soon broke down. At this point, the British re-asserted their claim on the islands, taking them over without loss of life in 1833. Exactly who left and who stayed has been disputed, with Argentina claiming the inhabitants were expelled,[11] but records of the time refer to several nationalities on the islands, living in conditions of lawlessness.[12] A full colony was not established until 1841, after law and order had been restored, and it gradually grew as a useful waystation for ships undertaking length voyages around the Americas and to Antarctica.

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ Gov.uk: 'Supporting the Falkland Islanders' rights'. 31st July 2013.

- ↑ BBC News: 'Falkland Islands: What are the competing claims?'. 16th February 2012.

- ↑ Falkland Islands Government Policy Unit: 'Falkland Islands Census 2012: Headline Results'. .pdf document.

- ↑ Falkland Islands Government: 'Our people'.

- ↑ Guardian: 'Argentina warns against oil drilling around Falkland Islands'. 7th November 2013.

- ↑ Channel 4 FactCheck Q&A: 'Why are the Falklands British?' 3rd April 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Department of State: 'U.S. Relations With Argentina'.

- ↑ Biblioteca Digital de Tratados [Digital Library of Treaties]: 'Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation'.

- ↑ Channel 4 FactCheck Q&A: 'Why are the Falklands British?' 3rd April 2012.

- ↑ Falkland Islands Government: 'Our History'.

- ↑ Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto: 'La Cuestión de las Islas Malvinas' [Ministry of Foreign Affairs: The Question of the Malvinas Islands]. In Spanish. Automatic English translation by Google Translate.

- ↑ Darwin Online: 'FitzRoy, R. 1839. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle's circumnavigation of the globe. Proceedings of the second expedition, 1831-36, under the command of Captain Robert Fitz-Roy, R.N. London: Henry Colburn.'.

KSF

KSF