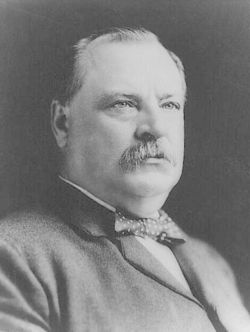

Grover Cleveland

From Citizendium - Reading time: 11 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 11 min

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th President of the United States of America, and the only President to serve two non-consecutive terms (1885–1889 and 1893–1897). He was the only Democrat elected to the Presidency in the era of political domination called the Third Party System between 1860 and 1896. His admirers praise him for his bedrock honesty, independence, integrity, and commitment to the principles of classical liberalism. As a leader of the Bourbon Democrats, he opposed imperialism, high taxes, corruption, patronage, subsidies and inflationary policies.

Some of Cleveland's actions were controversial with political factions: his intervention in the Pullman Strike of 1894 in order to keep the railroads moving angered labor unions, and his support of the gold standard and opposition to free silver alienated the agrarian wing of the party. Furthermore, critics complained that he had little imagination in dealing with the Panic of 1893. He lost control of his party to the agrarians and silverites in 1896.

Early life[edit]

Cleveland was born in Caldwell, New Jersey to the Reverend Richard Cleveland and Anne Neal. He was the fifth of nine children, five sons and four daughters. He was named Stephen Grover in honor of the first pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Caldwell, where his father was pastor at the time. From 1841 to 1850, he lived in Fayetteville, New York [2], but as the church frequently transferred its ministers, the family moved many times, mainly around central and southern New York State.

He became involved in Democratic politics at the age of 19 when he worked for the presidential campaign of James Buchanan. Following Buchanan's single term, the next Democrat elected president would be Cleveland himself, almost thirty years later.

During the Civil War, Cleveland met the draft order of 1863 by hiring a substitute to take his place.

As a lawyer in Buffalo, New York, he became notable for his single-minded concentration upon whatever task faced him. He was elected sheriff of Erie County, New York (centered on Buffalo) in 1871 and, while in that post, carried out at least two hangings of condemned criminals, refusing to delegate the unpleasant task to others. Political opponents would later hold this against him, calling him the "Buffalo Hangman." Cleveland stated that he wished to take the responsibility for the executions himself and not pass it along to subordinates.

The Influence of his Early Life[edit]

Kelley (1966) has studied the influence of early Calvinistic training on Cleveland's economic and political thought. Cleveland's early childhood in central New York was permeated by Presbyterian orthodoxy. The Shorter Catechism, with its stern emphasis upon duty and doctrine, was his religious primer. Cleveland's later public conduct illustrated the strength of his early religious training; he felt it his duty, as chief executive, to foster patriotism and morality. Kelley depicts Cleveland the "ideal" Calvinist type - a strong, stable, vigorous, humble, uncompromising, and moral man. The Presbyterian paradox of optimism combined with pessimism in Cleveland was reinforced by a Jacksonian naïveté on political and economic issues. He tended to seek simple panaceas and he invariably assumed that economic interests were inherently corrupt.

Political career[edit]

Running as a reformer, Cleveland was elected Mayor of Buffalo in 1881, with the slogan "Public Office is a Public Trust" as his trademark of office. One newspaper, in endorsing him, said it did so for three reasons: "1. He is honest. 2. He is honest. 3. He is honest." In 1882, he was elected Governor of New York, working closely with reform-minded Republican state legislator Theodore Roosevelt.

Blodgett (1992) surveys the political rise of Grover Cleveland from his 1870 election as Erie County Sheriff through his election to the presidency in 1884. Cleveland reflected his conservative Presbyterian upbringing and the cultural ambiguities of the Gilded Age. He viewed men as basically sinners and stressed probity in politics. He compiled a record of moderate reform. While governor of New York during 1881-82, he supported the nation's first state civil service act. His election as president resulted partly from the support of young reformers attracted by his promise of civil service reform and his honest behavior. Yet his campaign suffered from controversy when it was revealed he had fathered an illegitimate child. His reform supporters saw this as a bachelor fulfilling a sexual urge with a consenting woman. Cleveland's election, however, did not represent a major shift in voting patterns nor did it bring a big change in political policies.

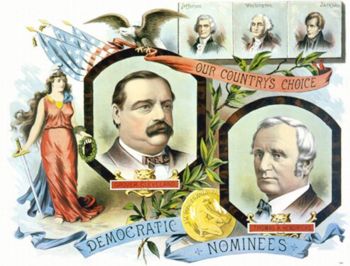

1884 campaign[edit]

Cleveland won the presidency in the 1884 election with the unusual combination of support from both Democrats and reform-minded Republicans called "Mugwumps" who denounced his opponent, former Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, as corrupt.

The campaign was negative. To counter Cleveland's image of purity, his opponents reported that Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate child while he was a lawyer in Buffalo. The derisive phrase "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?", was often chanted at Republican political rallies.

Cleveland admitted to paying child support in 1874 to Maria Crofts Halpin, the woman who claimed he fathered her child named Oscar Folsom Cleveland. Halpin was involved with several men at the time, including Cleveland's law partner and mentor, Oscar Folsom, for whom the child was named. (Cleveland is believed to have assumed responsibility because he was the only bachelor among them.) After Cleveland's election as President, Democratic newspapers added a line to the chant used against Cleveland and made it: "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa? Gone to the White House! Ha Ha Ha!"[1]

The desire for reform, blunders on behalf of Blaine, and voters demand for honesty turned the tide for Cleveland, who won narrowly. He carried his home base of New York, and therefore had a majority in the electoral college, becoming the first Democrat to become president since James Buchanan, in 1856.

First term as President (1884-1888)[edit]

Politics[edit]

Cleveland's administration might be characterized by his saying: "I have only one thing to do, and that is to do right". Cleveland faced a Republican Senate and often resorted to using his veto powers. Cleveland himself insisted that, as President, his greatest accomplishment was blocking others' bad ideas. He vigorously pursued a policy barring special favors to any economic group. Vetoing a bill to appropriate $10,000 to distribute seed grain among drought-stricken farmers in Texas, he wrote: "Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character...."

Cleveland angered veterans by vetoing hundreds of private pension bills to Civil War veterans whose claims he decided were fraudulent. When Congress, pressured by the Grand Army of the Republic, passed a bill granting pensions for disabilities not caused by military service, Cleveland vetoed that, too. Cleveland's 1887 decision to return captured battle flags to former Confederate states drew a storm of protest from the North and the ire of the powerful veterans organization the Grand Army of the Republic, prompting him to withdraw his edict.

Cleveland used the veto far more often than any President up to that time. Cleveland had an essentially negative view of Presidential power, telling a friend that his principal duty and greatest service to the country was in preventing Congress from enacting bad bills. He also felt that if the constitution did not authorize it, he could not in good faith sign a bill into law.

Cleveland lived up to his reputation of running an efficient government. He demanded his administration get rid of extravagances and abuses. Civil service reformers believed that the future of the republic was at stake in their efforts to end the corrupt spoils system, and they banked on Cleveland. At the start it appeared that Cleveland would vigorously enforce the 1883 Pendleton Act, but dissatisfaction grew as it became apparent that the president's interpretation of the spoils system exempted rewards to party faithful. In the end, Cleveland's successor, Benjamin Harrison, rescinded what advances were made in the area of unclassified service, and newer issues began to occupy the public's interest.[2]

In 1885, Cleveland ordered the Army to stop the raids on ranchers by Apaches under Chief Geronimo; in 1886 Geronimo was captured.

President Cleveland angered railroad investors by ordering an investigation of western lands they held by government grant, involving the return of 81,000,000 acres because the railroads failed to extend their lines according to agreements. The lands were forfeited and became part of public domain.

He signed the Interstate Commerce Act, the first law attempting Federal regulation of the railroads.

Foreign policy[edit]

Cleveland was a committed isolationist who had campaigned in opposition to expansion and imperialism. He reversed policy and withdrew the treaty for the annexation of Hawaii (U.S. state) negotiated by Benjamin Harrison from the consideration of the Senate. Cleveland often quoted the advice of George Washington's Farewell Address in decrying alliances, and he slowed the pace of expansion that President Chester Arthur had begun. Cleveland refused to promote Arthur's Nicaragua canal treaty, calling it an "entangling alliance". Free trade deals (reciprocity treaties) with Mexico and several South American countries died because there was no Senate approval. Cleveland supported Hawaiian reciprocity and accepted an amendment that gave the United States a coaling and naval station in Pearl Harbor. Ship orders were placed with Democratic industrialists rather than Republican ones, as the Navy was modernized. Under Cleveland, the U.S. adopted a broad interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine that did not just simply forbid new European colonies but declared an American interest in any matter within the hemisphere.

Crusade against protective tariff[edit]

In December 1887, Cleveland called on Congress to reduce high protective tariffs:

The theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him... the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and a culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice. This wrong inflicted upon those who bear the burden of national taxation, like other wrongs, multiplies a brood of evil consequences. The public Treasury... becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder.

He failed to lower tariffs when the Mills bill failed, and made it the central issue of his losing 1888 campaign, as Republicans under William McKinley claimed a high tariff was needed to produce high wages, high profits, and fast economic expansion.

Personal life[edit]

In June 1886, Cleveland married Frances Clara Folsom, the daughter of his former law partner, in the in the White House. He was the second President to be married while in office, and the only President to have a wedding in the White House itself. This marriage was controversial because Cleveland was the executor of the Folsom estate and supervised Frances' upbringing. Folsom, at 21 years old, was the youngest First Lady in the history of the United States. With his wife, Grover had five children: Ruth Cleveland (1891-1904); Esther Cleveland (1893-1980); Marion Cleveland (1895-1977); Richard Folsom Cleveland (1897-1974); Francis Grover Cleveland (1903-1995).

1888 campaign[edit]

Cleveland was defeated in the 1888 presidential election. He actually led in the popular vote over Benjamin Harrison (48.6% to 47.8%), but Harrison won the Electoral College by a 233-168 margin, largely by his narrow win in Cleveland's home state of New York.

1892 Campaign[edit]

The primary issues for Cleveland for the 1892 campaign were reducing the tariff and reversing the high spending of the Republican "billion dollar" Congress. The Democrats mobilized Catholic and Lutheran voters outraged at nativist efforts to close their German-language parochial schools.[3] Cleveland was elected again in 1892, thus becoming the only President in U.S. history to be elected to a second term which did not run in succession to the first.

Administration (1893-1897)[edit]

Politics[edit]

Shortly after Cleveland was inaugurated, the Panic of 1893 struck and the economy went into a deep depression that lasted four years. He dealt directly with the Treasury crisis rather than with business failures, farm mortgage foreclosures, and unemployment. He obtained repeal of the mildly inflationary Sherman Silver Purchase Act. With the aid of J. P. Morgan and Wall Street, he maintained the Treasury's gold reserve.

He fought to lower the tariff in 1893-1894. The Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act introduced by West Virginian Representative William L. Wilson and passed by the House would have made significant reforms. However, by the time the bill passed the Senate, guided by Democrat Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, it had more than 600 amendments attached that nullified most of the reforms. The "Sugar Trust" in particular made changes that favored it at the expense of the consumer. It imposed an income tax of two percent to make up for revenue that would be lost by tariff reductions. Cleveland was devastated that his program had been ruined. He denounced the revised measure as a disgraceful product of "party perfidy and party dishonor," but still allowed it to become law without his signature, believing that it was better than nothing and was at the least an improvement over the McKinley tariff.

Cleveland refused to allow Eugene Debs to use the Pullman Strike to shut down most of the nation's passenger, freight and mail traffic in June 1894. He obtained an injunction in federal court, and when the strikers refused to obey it, he sent in federal troops to Chicago and 20 other rail centers. "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postcard in Chicago," he thundered, "that card will be delivered." Most governors supported Cleveland except Democrat John P. Altgeld of Illinois, who became his bitter foe in 1896.

Cleveland's agrarian and silverite enemies seized control of the Democratic party in 1896, repudiated his administration and the gold standard, and nominated William Jennings Bryan on a Silver Platform. Cleveland silently supported the National Democratic Party (United States) (or "Gold Democratic") third party ticket that promised to defend the gold standard, limit government, and oppose high tariffs. The party won only 100,000 votes in the general election (just over 1 percent). Agrarians again nominated Bryan in 1900, but in 1904 the conservatives, with Cleveland's support, regained control of the Democratic Party and nominated Alton B. Parker.

Foreign affairs[edit]

Invoking the Monroe Doctrine in 1895, Cleveland forced Britain to agree to arbitration of a disputed boundary in Venezuela. His administration is credited with the modernization of the United States Navy that allowed the U.S. to decisively win the Spanish-American War in 1898, one year after he left office.

Hawaii[edit]

When Cleveland took office he faced the question of Hawaiian annexation. Honolulu businessmen (Hawaiian citizens of European and American ancestry) had denounced Queen Liliuokalani as a tyrant who rejected constitutional government; in early 1893 they overthrew her, and set up a Republic. An American diplomat supported the overthrow. Cleveland withdrew the treaty of annexation that Harrison had submitted to the Senate pending a fact-finding mission by a special envoy. For the mission, he chose former Georgia Congressman James H. Blount, whose anti-imperialist attitudes figured to support the positions of three key Southern cabinet members who opposed annexation. Blount did indeed recommend the rejection of annexation, and stated that the natives should be allowed to continue their Asiatic ways. (The natives in fact had little or no voice in the Queen's government because she hired European advisors.) When Blount blamed the U.S. assistance for the overthrow Cleveland proposed to use American military force to overthrow the Republic and reinstall Liliuokalani as an absolute monarch. The proposal was a dramatic reversal of American republicanism and support for democracy, and lost Cleveland popular support. When the deposed Queen refused to grant amnesty as a condition of her reinstatement, and said she would behead the current government leaders and confiscate their property Cleveland was further humiliated at the realization he was trying to put a tyrant back on her throne. He referred the matter to Congress. The Senate, angered at being shut out by Cleveland, then produced the Morgan Report, which completely contradicted Blount's findings and found the overthrow was a completely internal affair. Following the Turpie Resolution of May 1894, which vowed a policy of non-interference in Hawaiian affairs, Cleveland dropped all talk of reinstating the Queen, and went on to officially recognize and maintain diplomatic relations with the Republic of Hawaii. Other nations had already recognized the Republic. In 1898 the Republic again sought annexation, which with McKinley's strong support won Congressional approval, despite racist fears that the Asians and natives could never be assimilated.[4]

Women's rights[edit]

Cleveland was a stout opponent of the women's suffrage (voting) movement. In a 1905 article in The Ladies Home Journal, Cleveland wrote, "Sensible and responsible women do not want to vote. The relative positions to be assumed by men and women in the working out of our civilization were assigned long ago by a higher intelligence." * [3]

Later life and death[edit]

After leaving the White House, Cleveland lived in retirement at his estate in Princeton, New Jersey. For a time he was a trustee of Princeton University, bringing him into opposition to the school's president, Woodrow Wilson. Conservative Democrats hoped to nominate him for another presidential term in 1904, but his age and health forced them to turn to other candidates. Cleveland consulted occasionally with President Theodore Roosevelt, but was financially unable to accept the chairmanship of the commission handling the Coal Strike of 1902.

Cleveland died in 1908 from a heart attack, with his wife at his side. He is buried in the Princeton Cemetery of the Nassau Presbyterian Church.

Honors and memorials[edit]

Cleveland's portrait was on the U.S. $1000 bill from 1928 to 1946. Since he was both the 22nd and 24th President, he will be featured on two separate dollar coins to be released in 2012 as part of the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005.

In 2006, Free New York, a nonprofit and nonpartisan research group, began raising funds to purchase the former Fairfield Library in Buffalo, New York and transform it into the Grover Cleveland Presidential Library & Museum.[4]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ President Cleveland’s Problem Child: Not even a specific allegation of philandering, illicit pregnancy and coverup barred Grover Cleveland from the White House, Smithsonian Magazine online September 26, 2013, last access 11/22/2022

- ↑ Justus Doenecke, "Grover Cleveland and the Enforcement of the Civil Service Act." Hayes Historical Journal 1984 4(3): 44-58. Issn: 0364-5924

- ↑ Jensen (1971)

- ↑ Tennant S. McWilliams, "James H. Blount, the South, and Hawaiian Annexation." Pacific Historical Review 1988 57(1): 25-46. Issn: 0030-8684 Fulltext: in Jstor; Dewey (1905) ch 19 pp 297-304 is online at [1]

KSF

KSF