Guantanamo Bay detention camp

From Citizendium - Reading time: 9 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 9 min

| This article may be deleted soon. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

The Guantanamo Bay detention camp, or Guantanamo detention camp, are unofficial terms for a prison facility at Naval Station Guantanamo Bay on a U.S.-leased area in Cuba. Official documents (such as the Executive Order from President Barack Obama that states his intention to close it) refer to the detention facilities at Guantánamo.[1]. The camp is run by Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO), which is part of United States Southern Command.

Like other bases outside the territory of the U.S.A., the camp is under military jurisdiction rather than that of the U.S. civilian justice system. This is, however, a complex and controversial legal issue. It holds the 14 High Value Detainees that were earlier held in secret detention facilities operated by the Central Intelligence Agency. Additional CIA detainees never appeared at Guantanamo, and are believed to have been sent to third countries. This base was one of several detention facilities for persons captured in the Afghanistan War (2001-2021), along others such as the Bagram Airfield). The George W. Bush Administration ruled that these were not entitled to prisoner of war status under the Third Geneva Convention. Subsequent concerns about their treatment led to the Detainee Treatment Act [3] and rulings, including Rasul v. Bush and Boumediene v. Bush, by the Supreme Court of the United States. On January 22, 2009, incoming President Barack Obama announced its intention to close the facility.[1] Creation and organization[edit]On January 4, 2002, United States Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) was told to take custody of designated detainees within the United States Central Command area of responsibility, and to hold them at a facility to be built at the Naval Station Guantanamo Bay. This task was assigned to Joint Task Force 160 (JTF 160). JTF 160 was principally a security operation, with a core of military police fom all the services; more than 1,000 U.S. service members, commanded by U.S. Marine Corps BG Michael Lenhart were sent to Guantanamo Bay to provide security for the detainees. In addition, on 22 January 2002, the Secretary of Defense directed Southern Command to implement a Department of Defense/Interagency interrogation effort. This became the responsibility of Joint Task Force 170 (JTF 170),[4] commanded by MG (U.S. Army Reserve) Michael E. Dunleavey, an intelligence officer on active duty, who had been a trial attorney in civilian life. JTF 170's mission included strategic intelligence collection, force protection, and law enforcement and tribunal activities.[5] Interrogations, however, were not necessarily intended to meet the evidentiary or procedural needs of tribunal or law enforcement processes; the emphasis was on information gathering for counterterrorism. Southern Command had the two task forces working in parallel, establishing the Joint Interagency Interrogation Facility (JIIF) on January 22. In March 2002, BG Rick Baccus and a Rhode Island Army National Guard Military Police Brigade were sent to Guantanamo, replacing the ad hoc Marine-based unit with military police.[6] Baccus was a Military Police officer, but not experienced in prison operations. While penology falls generally under a police and judicial function, they are separate specialties; while the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is part of the U.S. Department of Justice, the Bureau of Prisons is a separate organization with different organization and training. Even in the FBI, counterterorrism intelligence is a relatively new and specialized function, different from their traditional roles in law enforcement and counterespionage. Denying that it was his job to gather intelligence, explaining that that role was assigned to JTF 170,Baccus said

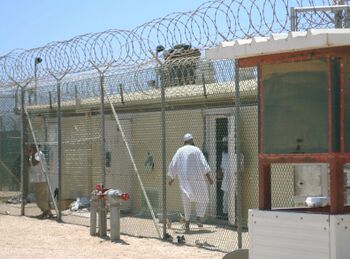

Merger: JTF-GTMO[edit]On August 27, 2002, GEN James T. Hill became the new commander of USSOUTHCOM. He knew MG Geoffrey Miller as a competent general military commander, and chose him to command JTF-GTMO on November 4, 2002. Some reports said that Baccus was relieved,[7] but he countered that he was decorated for service, given an outstanding performance review, and JTF-160 received the "Joint Unit Meritorious Award for their time period in Guantanamo, of which I was the commander of that joint task force seven out of the nine months in the period of time of the award. ...my leaving Guantanamo was on a part of a plan to join the two task forces together. I left on the seventh of October; Miller was in place on the first of November."[6] Policy Changes[edit]By the summer of 2002, top-level commanders were dissatisfied with the quality of information coming from detainees in all locations. The GTMO command requested permission to use intensified methods in October 2002; while these were first reported to be Guantanamo-specific, they were part of an overall review in the Defense Department, and, under White House and Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel policy direction, government-wide. Legal status of detainees[edit]While the legal status continues to develop, both as a result of a new Administration and ongoing court actions, the principal legal guidance comes from the Detainee Treatment Act and the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Susan Crawford is now the convening authority for military commissions. President Obama, almost immediately after taking office, repudiated the most recent Executive Order of the Bush Administration. In early 2004, the Department of Defense made recommendations to provide a semi-public program to review the captives' status.[8] Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRT) were held in small rooms, with three chairs for press observers. Only 37 of the 574 Tribunals were observed.[9] Annual Administrative Review Board hearings were convened for captives who had been determined, by a CSRT, to be an enemy combatant. [10] In the summer of 2004 Donald Rumsfeld, the Secretary of Defense created the Office for the Administrative Review of Detained Enemy Combatants (OARDEC), to be headed by a "Designated Civilian Official" (DCO), and appointed Gordon England as the first Designated Civilian Official. England was the Secretary of the Navy at the time. When England was promoted to Deputy Secretary of Defense, he remained the Designated Civilian Official. Supreme Court rulings[edit]As a result of legal challenges brought to the Bush Administration's detention policy, the United States Supreme Court has made two important rulings regarding the detainees at Guantánamo Bay. In Rasul v. Bush the Supreme Court ruled that the Bush administration had to provide a venue for the captives to learn the reasons why they were being detained, and give them an opportunity to refute those allegations.[11] More far-reaching was the decision in Boumediene v. Bush which was decided June 12, 2008. In this case, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 majority that the Military Commissions Act of 2006 violated the detainees' constitutional right of habeas corpus. At the core of the legal argument of the Bush administration in denying detainees habeas corpus in U.S. federal court was its contention that Guantánamo Bay under the 1903 U.S.-Cuban lease remains part of Cuban sovereign territory and that therefore U.S. constitutional protections did not extend there. Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing for the majority, rejected that argument and ruled that a situation of "de facto sovereignty" exists which entitles detainees to U.S. federal protections.[12] Military commissions at Guantanamo[edit]In 2004 President Bush authorized the Office of Military Commissions to charge and try Guantanamo captives, which subsequently charged ten captives. However, in July 2006 the Supreme Court ruled that the President lacked the constitutional authority to set up Military commissions, declaring that only the United States Congress had that authority. This led to the passing of the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Twenty captives have since been charged under the Congressionally authorized Commissions. Most of the captives who originally faced charges have faced new and different charges under the new Commissions. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Abraham came forward and swore an affidavit,[13] describing his experience on a Tribunal.[14] Guantanamo captives' living conditions[edit]The first captives were housed in open-air cages in Camp X-ray, in the northeast corner of the base.[15] As the number of captives grew, Camp X-Ray was closed, and Camp Delta was opened near the coast. At its high point it held about 650 captives (in all about 780 captives have been held there). 558 captives had their enemy combatant status reviewed by Combatant Status Review Tribunals in late 2004, or January 2005. The Board hearings were authorized to establish whether particular captives continued to be a threat, or continued to hold "intelligence value.[8] These determined the 'Security Level of each detainee, which to some extent determined where in the camp he was housed and how he was treated. Most Level 1 detainees were held in Camp 4: [16]

There have been several hunger strikes by detainees, and some protesters have been force-fed. [17] Several inmates petitioned against force-feeding, but Gladys Kessler, judge for the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, rejected their petition. [18] Process of closure[edit]Barack Obama had made a campaign promise to close the detention facility located at the naval base. On January 22, 2009 the president signed an executive order to close the detention camp within one year,[1]stating that the U.S. did not need "to continue with a false choice between our safety and our ideals."[19] More recently, the president's Deputy National Security Adviser for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism John Brennan said that another important reason to push for closure of the detention camp was its use as a propaganda tool by Al-Qaeda.[20] On December 15, 2009, the president announced that the Thomson Correctional Center in Thomson, Illinois (U.S. state) would be acquired by the federal government to house high-security prisoners currently at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.[21] The Obama Administration has not met its original one-year goal of closure, but actions are accelerating at the end of 2009. Since 2002, 568 prisoners have been held and 198 remain.

Various legal groups had, for some time, been arguing not only for trial in civilian courts, but questioned the indefinite military detention of the 100 to be transferred to prison. One such petition, created by Human Rights First and the Constitution Project, is called "Beyond Guantanamo". References[edit]

|

|||

KSF

KSF