Herbert Hoover

From Citizendium - Reading time: 19 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 19 min

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

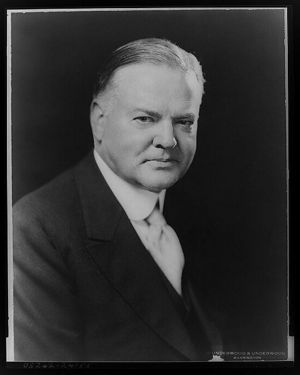

Herbert Hoover, 1928 (Library of Congress)

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was a American mining engineer, humanitarian, administrator, author, and Secretary of Commerce who was elected the 31st President of the United States. Elected in 1928, his associationalist policies were unable to reverse the decline into the Great Depression. He began massive subsidies of business and make-work programs, but nothing on the scale advocated by his successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt. His name became synonymous with failed policies. In his long post-presidential career he staked out an isolationist foreign policy and served two presidents after World War II on committees seeking to improve government efficiency.

Family background[edit]

Hoover's original surname was Huber. He was born in in West Branch, Iowa, into a Quaker family of distant German (Pfautz, Wehmeyer) and Swiss (Huber, Burkhart) descent. He was the first President to be born west of the Mississippi River. Both of his parents died when Hoover was young. His father, Jesse Hoover died in 1880, and his mother, Hulda Minthorn, died in 1883.

In 1885, when "Bert" Hoover was 11, he went to Newberg, Oregon to become the ward of his uncle John Minthorn. Minthorn was a doctor and real estate developer who Hoover recalled as "a severe man on the surface, but like all Quakers kindly at the bottom."

At a young age, Hoover was self-reliant and ambitious. "My boyhood ambition was to be able to earn my own living, without the help of anybody, anywhere," he once said. As an office boy in his uncle's Oregon Land Company he excelled in bookkeeping and typing, while also attending business school in the evening. Thanks to a local schoolteacher, Miss Jane Gray, the young Hoover was introduced to the novels of Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. David Copperfield, the story of another orphan cast into the world, was Hoover's lifelong favorite.

Education[edit]

In the fall of 1891, Hoover entered the new Leland Stanford Junior University in California (U.S. state). Outside the classroom than in, Hoover managed the baseball and football teams, started a laundry, and ran a lecture agency. With the support of other students from less wealthy backgrounds against campus "swells," the reluctant candidate was elected student body treasurer on the "Barbarian" slate; he then cleared a student-government debt of $2,000.

Hoover's major was geology. He studied with Professor John Casper Branner. Branner also helped Hoover getting summer jobs mapping terrain in Arkansas (U.S. state)' Ozark Mountains and in Colorado. In Branner's class, Hoover met Lou Henry, a banker's daughter from Waterloo, Iowa. Lou shared her fellow Iowan's love of the outdoors and the nature of self-reliance. Lou said, "It isn't so important what others think of you as what you feel inside yourself".

Mining engineer[edit]

After graduating from Stanford University in 1895 with a degree in geology, Hoover was unable to find a job as a mining engineer, so he worked as a clerk with the San Francisco, California consulting firm of Louis Janin. Hoover so impressed Janin that when the British mining firm, Bewick, Moering & Co. asked Janin to suggest an engineer to work for them in Australia, he recommended Hoover.

Hoover arrived in Albany, Western Australia, in May 1897, and spent the next one and one-half years planning development work, ordering and laying out equipment, and examining new prospects. Hoover often traveled to outlying mines by camel, which he called "even a less successful creation than a horse." On one of his trips, he made a detailed inspection of a new mine called the "Sons of Gwalia," which he recommended that his company buy. In time, it proved to be one of the richest gold mines in the world.

After less than two years in Australia, Bewick, Moering & Co. offered Hoover a position to oversee the development of coal mines in China. With the job offer in hand, Hoover cabled Lou Henry with a proposal of marriage. Herbert traveled to China by way of the United States, and on February 10, 1899, he and Lou Henry were married in the sitting room of her parents' home in Monterey, California. They would have two children: Herbert Jr. (August 4, 1903 - July 9, 1969) and Allan (July 17, 1907 - November 4, 1993).

The Hoovers arrived in China in March 1899, and he carried out the complex task of balancing his corporation's interests in developing coal mines with local officials' demands for locating new sources of gold. Early in 1900, a wave of anti-western feeling swept China and a nativist movement called "I Ho Tuan," or the Boxers, resolved to destroy all foreign industries, railways, telegraphs, houses and people in China. In June 1900, the Hoovers, along with hundreds of foreign families, were trapped in the city of Tianjin, protected only by a few soldiers from several foreign countries. Hoover helped organize defensive barricades and organize food supplies, and Lou helped out at the hospital. Tianjin was relieved in late July, and the Hoovers were able to leave for London.

Just before leaving, Hoover and his colleagues set in motion a complex scheme to protect the mining operations from being seized or destroyed by reorganizing the Chinese Engineering and Mining Company as a British corporation under control of Bewick, Moering and Company. In January 1901, after the rebellion had been put down, Hoover returned to China to complete the restructuring of the company. Hoover oversaw the repairs necessary after the Rebellion, restarted the operations, and began opening new mines. A few months later, Bewick, Moering and Company offered Hoover a junior partnership in their firm, and the Hoovers left China.

Between 1907 and 1912, Hoover and his wife combined their talents to create a translation of one of the earliest printed technical treatises: Georg Agricola's De re metallica, originally published in 1556. At 670 pages, with 289 woodcuts, the Hoover translation remains the definitive English language translation of Agricola's work.

Humanitarian[edit]

Bored with making money, the Quaker side of Hoover yearned to be of service to others. When World War I started in August 1914, he helped organize the return home of 120,000 American tourists and businessmen from Europe. Hoover led five hundred volunteers to distribute food, clothing, steamship tickets and cash. "I did not realize it at the moment, but on August 3, 1914 my engineering career was over forever. I was on the slippery road of public life." The difference between dictatorship and democracy, Hoover liked to say, was simple: dictators organize from the top down, democracies from the bottom up.

Belgium faced a food crisis after being invaded by Germany in fall 1914. Hoover undertook an unprecedented relief effort as head of the Commission for the Relief of Belgium (CRB). The CRB became, in effect, an independent republic of relief, with its own flag, navy, factories, mills and railroads. Its $12-million-a-month budget was supplied by voluntary donations and government grants. In an early form of shuttle diplomacy, he crossed the North Sea forty times seeking to persuade the enemies in Berlin to allow food to reach the war's victims. Long before the Armistice of 1918, he was an international hero. The Belgian city of Leuven named a prominent square after him.

After the United States entered the war in April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson appointed Hoover head of the American Food Administration, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. He succeeded in cutting consumption of food needed overseas and avoided rationing at home. After the end of the war, Hoover, a member of the Supreme Economic Council and head of the American Relief Administration, organized shipments of food for millions of starving people in Central Europe. To this end, he employed a newly formed Quaker organization, the American Friends Service Committee to carry out much of the logistical work in Europe. He extended aid to famine-stricken Bolshevist Russia in 1921. When a critic inquired if he was not thus helping Bolshevism, Hoover retorted, "Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!"

During this time, Hoover realized that he was in a unique position to collect information about the Great War and its aftermath. In 1919, he pledged US$50,000 to Stanford University to support his Hoover War Collection and donated to the University the extensive files of the Commission for Relief in Belgium, the U.S. Food Administration, and the American Relief Administration. Scholars were sent to Europe to collect pamphlets, society publications, government documents, newspapers, posters, proclamations, and other ephemeral materials related to the war and the revolutions and political movements that had followed it. The collection was later renamed the Hoover War Library and is now known as the Hoover Institution.

Commerce Secretary[edit]

Hoover, whose politics were somewhat ambiguous prior to 1920, was courted by both political parties, with the Democrats suggesting even a presidential bid. But, when he announced his support for Warren G. Harding, all negotiations with the Democrats stopped. After the election, Harding nominated Hoover as Secretary of Commerce, one of Harding's few appointees not beholden to the Republican machine. As Commerce Secretary, Hoover became one of the most visible men in Harding's Administration, and probably the most dynamic secretary ever of that department. His popularity and press often overshadowed his bosses, Presidents Harding and Calvin Coolidge. As secretary, and then later as President, Hoover revolutionized the relations between business and government. Rejecting the adversarial stance of Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson, he sought to make the Commerce Department a powerful service organization, empowered to forge cooperative voluntary partnerships between government and business. This philosophy is often called "associationalism."

Many of Hoover's efforts as Commerce Secretary centered on efficiency and the elimination of waste in business and industry. Thus his policies attempted to reduce labor losses from trade disputes and seasonal fluctuations, or to reduce industrial losses from accident and injury, or to reduce the amount of crude oil spilled during extraction and shipping. One major goal he achieved was to promote standardization products and designs. He energetically promoted international trade by opening offices overseas that gave advice and practical help to businessmen. He was especially eager to promote U.S. films overseas.[1] His "Own Your Own Home" collaborative campaign with builders, real estate promoters, and bankers increase single-family home-ownership. The campaign included the Better Houses in America movement, the Architects' Small House Service Bureau, and the Home Modernizing Bureau. He worked with bankers and the savings and loan industry to promote the new long-term home mortgage, which dramatically stimulated home construction.[2]

Among Hoover's other successes were the industries of radio, navigation, irrigation and flood control, electricity, and airlines. To promote radio, Hoover organized radio conferences, which played a key role in the early organization, development and regulation of radio broadcasting. For the new air transport industry, Hoover held a conference on aviation to promote codes and regulations.

He was elected president of the American Child Health Organization, and he raised private funds to promote health education in schools and communities.

By the spring of 1927, Hoover's reputation as a man who can get industry up and running or to promote aid in a humanitarian crisis was at its peak. During the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, governors of six states along the Mississippi demanded that the federal government send them Herbert Hoover in the emergency. President Coolidge obliged, and Hoover mobilized state and local authorities, militia, army engineers, Coast Guard, and the American Red Cross. With a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, he set up health stations to work in the flooded regions for a year. These health workers stamped out malaria, pellagra and typhoid fever from many areas. His work during the flood brought Herbert Hoover to the front page of newspapers almost everywhere.

Election of 1928[edit]

In 1928, when President Coolidge did not run for a second term of office, Herbert Hoover was called to become the Republican Party candidate. Hoover’s reputation, experience, and popularity together gave him the Republican presidential nomination. He ran against Al Smith and campaigned on efficiency and prosperity. Although Smith was the target of anti-Catholicism from the Baptist and Lutheran communities, Hoover avoided the religious issue. (Quakers were themselves under attack as pacifists.) He supported prohibition tentatively and called it a "noble experiment". Hoover's reputation nationwide and the economic boom, combined with the deep chasm among the Democrats over religion and prohibition, led to his landslide victory. Also, important was Hoover's distance from the Harding Administration's taint of corruption that most Americans associated with machine politics and Smith's close association with the Tammany machine.[3]

On the issue of poverty Hoover said optimistically, "We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land." However, within months, the American economy sunk drastically into the Great Depression after the Stock Market Crash of 1929 occurred.

Presidency 1929-1933[edit]

Policies[edit]

Although Hoover presidency generally received negative comments, it should be noted that the Hoover administration did carry out some important reform policies.

Some of the reform policies Hoover implemented included the expansion of coverage of civil service, the cancellation of private oil leases on government lands, the leading the way for the prosecution of notorious gang leader Al Capone. He also advocated tax reduction for low-income Americans and doubled the numbers of veteran hospital facilities. Hoover appointed a commission which set aside 3 million acres (12,000 km²) of national parks and 2.3 million acres (9,000 km²) of national forests.

He negotiated a treaty on St. Lawrence Seaway but failed in the U.S. Senate. He signed an act that made The Star-Spangled Banner the national anthem, wrote a Children's Charter that advocated protection of every child regardless of race or gender, built the San Francisco Bay Bridge, created an antitrust division in the Justice Department, required air mail carriers to improve service, and proposed federal loans for clearance of urban slums.

Hoover organized the Federal Bureau of Prisons, reorganized the Bureau of Indian Affairs, proposed a federal Department of Education, advocated fifty-dollar-per-month pensions for Americans over 65, chaired White House conferences on child health, protection, homebuilding and homeownership, and signed the Norris-La Guardia Act that limited judicial intervention and outlawed the use of the injunction in labor disputes.

Hoover's humanitarian and Quaker reputation, along with a Native American in his administration, influenced his administration's Indian policy. He had spent part of his childhood in proximity to Indians in Oklahoma, and his Quaker upbringing influenced his views that Native Americans needed to achieve economic self-sufficiency. During his presidency, he appointed Charles J. Rhoads as commissioner of Indian affairs. He supported Rhoads' efforts to achieve Indian assimilation and sought to reduce the federal role in Indian affairs to the minimum. He wanted to have Indians acting as individuals instead of as tribes, and assuming the responsibilities of citizenship which had been granted pursuant to Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.[4]

Regarding to foreign policy, Hoover began steps which eventually were popularized as the Good Neighbor Policy by withdrawing American troops from Nicaragua and Haiti. These steps meant that the Roosevelt Corollary was no longer a part of U.S. foreign policy. He also proposed an arms embargo on Latin America and a one-third reduction in the size of the world's navies, which was called the Hoover Plan. He and Secretary of State Henry Stimson formulated the Stimson Doctrine that said the United States would not recognize territories gained by force.

Great Depression[edit]

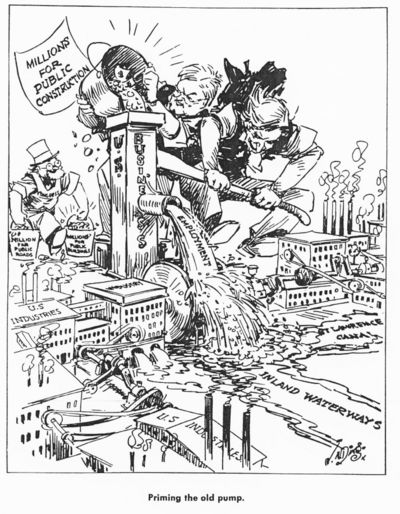

Nonetheless, despite these directions and initiatives of President Hoover, the greatest test of his presidency and character was the Great Depression. The economy was put to the test with the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Hoover was only by comparison (and in the political campaign rhetoric of 1932) a "do nothing" president. He also was not a firm believer laissez-faire policies although many in his republican administration were. He explicitly denounced laissez-faire in his 1922 book American Individualism, took an active pro-regulation stance as Commerce Secretary, and saw tariff and agricultural support bills through Congress. In his memoirs he recalled his rejection of Treasury Secretary Mellon's suggested "leave-it-alone" approach. However, Hoover opposed direct relief from the federal government, seeking instead to organize voluntary measures and encourage state and local government responses (a policy known as volunteerism). Except for accelerating public works expenditures, Hoover largely shunned legislative relief proposals until late in his term. While his efforts were small in comparison to that of the Roosevelt Administration, they exceeded that of any peace-time federal administration before him.

Soon after the stock market crash, Hoover summoned industrialists to the White House and secured promises to maintain wages. Henry Ford even agreed to increase workers' daily pay from six to seven dollars. From the nation's utilities, Hoover won commitments of $1.8 billion in new construction and repairs for 1930. Railroad executives made a similar pledge. Organized labor agreed to withdraw its latest wage demands. The President ordered federal departments to speed up construction projects. He contacted all forty-eight state governors to make a similar appeal for expanded public works. He went to Congress with a $160 million tax cut, coupled with a doubling of resources for public buildings and dams, highways and harbors. He appointed a Federal Farm Board that tried to raise farm prices.

Praise for the President's intervention was widespread. "No one in his place could have done more," concluded the New York Times in the spring of 1930. "Very few of his predecessors could have done as much." In February, Hoover announced--prematurely--that the preliminary shock had passed and that employment was on the mend.

Together government and business actually spent more in the first half of 1930 than the previous year. Yet frightened consumers cut back their expenditures by ten percent. A severe drough ravaged the agricultural heartland beginning in the summer of 1930 (see Dust Bowl). The combination of these factors caused a downward spiral: as individual earnings fell, smaller banks collapsed, and mortgages went unpaid. Hoover's hold-the-line policy in wages lasted little more than a year. Unemployment soared from five million in 1930 to over eleven million in 1931. A sharp recession had become the Great Depression.

During the 1928 campaign, the republicans had advocated raising tariff rates and Hoover introduced legislation early in 1929. Political wrangling held the bill up until 1930. By that time, his hold-the-line wage policy needed business support, and business, if it was expected to maintain high wages, needed protection from cheap foreign imports. Congress approved the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930. The law raised tariffs on over 20,000 dutiable items. The tariff, combined with the Revenue Act of 1932, which hiked taxes and fees (including postage rates) across the board, is often blamed for deepening the depression, and are considered by some to be Hoover's biggest political blunders. Moreover, the Federal Reserve System's tightening of the money supply (for fear of inflation) is regarded by Milton Friedman and most modern economists as a mistaken strategy given the situation.

Hoover's stance on dealing with the economic crisis was based on volunteerism. From before his entry to the presidency, he was among the greatest proponents of the concept that public-private cooperation was the way to achieve high long-term growth. Hoover feared that too much intervention or coercion by the government would destroy individuality and self-reliance, which he considered to be an important American value. Though he was not averse to government action when he considered it was in the public good, such as regulating radio broadcasting and aviation, he preferred a voluntary, non-government approach. Thus he encouraged Americans to find their own sources of relief such as city relief, churches, self-help or fraternal organizations, or community missions such as the Salvation Army. Unfortunately, after months and then years of such voluntary and local relief these organization were bankrupt. Cities, churches, and schools closed their doors. While moral ("God helps those who help themselves"), volunteerism was not sufficient enough to help most Americans who were in most dire need and certainly not sufficient to meet a crisis that lasted longer than a few months.

In June 1931, to deal with a very serious banking collapse in Central Europe that threatened to cause a worldwide financial meltdown, Hoover issued the Hoover Moratorium that called for a one-year halt in reparations payments by Germany to the Allies and in the payment of Allied war debts to the United States. The Hoover Moratorium had the effect of temporarily stopping the banking collapse in Europe. Then in June 1932, a conference canceled all reparations payments by Germany.

The following is an outline of other actions Hoover took to try to help end the Depression through government taxing and spending:

- Signed the Emergency Relief and Construction Act, the nation's first Federal unemployment assistance.

- Increased public works spending. Some of Hoover's efforts to stimulate the economy through public works are as follows:

- Asked Congress for a $400 million increase in the Federal Building Program.

- Directed the Department of Commerce to establish a Division of Public Construction in December 1929.

- Increased subsidies for ship construction through the Federal Shipping Board.

- Urged the state governors to also increase their public works spending, though many failed to take any action.

- Signed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act establishing the Federal Home Loan Bank system to assist citizens in obtaining financing to purchase a home.

- Increased subsidies to the nation's struggling farmers with the Agricultural Marketing Act; but with only limited impact.

- Established the President's Emergency Relief Organization to coordinate local private relief efforts resulting in over 3,000 relief committees across the U.S.

- In an effort to ease unemployment, he authorized the relocation to Mexico of 1-2 million people living in barrios throughout California, Texas and Michigan, sixty percent of whom were U.S. citizens of Mexican-descent.

- Urged bankers to form the National Credit Corporation to assist banks in financial trouble and protect depositors' money.

- Actively encouraged businesses to maintain high wages during the depression in line with the philosophy, called Fordism, that high wages create prosperity. Most corporations maintained their workers' wages early in the depression in the hope that more money into the pockets of consumers would end the economic downturn.

- Signed the Reconstruction Finance Act. This act established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which made loans to the states for public works and unemployment relief, and to banks, railroads, and agriculture credit organizations. Businesses tended to use the money to pay dividends rather than stimulate employment.

- Raised tariffs. After hearings held by the House Ways and Means Committee generated more than 20,000 pages of testimony regarding tariff protection, a lot of it urging higher tariffs would make the depression worse, Congress responded with legislation that Hoover signed despite some misgivings. While intending to protect American jobs, the Smoot-Hawley tariff set off a worldwide trade war which only worsened the country's (and the world's) economic ills.

Economy[edit]

In order to pay for these and other government programs, Hoover agreed to one of the largest tax increases in American history. The Revenue Act of 1932 raised taxes on the highest incomes from 25% to 63%. The estate tax was doubled and corporate taxes were raised by almost 15%. Also, a "check tax" was included that placed a 2-cent tax (over 30 cents in today's dollars) on all bank checks.[5] Hoover also encouraged Congress to investigate the New York Stock Exchange and this pressure resulted in various reforms.

For this reason, libertarians hold that Hoover's economics were statist. Franklin D. Roosevelt blasted the Republican incumbent for spending and taxing too much, increasing national debt, raising tariffs and blocking trade, as well as placing millions on the dole of the government. Roosevelt attacked Hoover for "reckless and extravagant" spending, of thinking "that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible," and of leading "the greatest spending administration in peacetime in all of history." Roosevelt's running mate, John Nance Garner, accused the Republican of "leading the country down the path of socialism". While good campaign rhetoric, Hoover's policies pale beside the more drastic steps taken later as part of the New Deal. However, Hoover's opponents charge that they came too little and too late. Even as he asked Congress for legislation, he reiterated his view that while people must not suffer from hunger and cold, caring for them must be primarily a local and voluntary responsibility.

Even so, New Dealer Rexford Tugwell later remarked that although no one would say so at the time, "practically the whole New Deal was extrapolated from programs that Hoover started."[6]

Unemployment rose to 24.9% by the end of Hoover's presidency in 1933, a year that is considered to be the depth of the Great Depression.

1932 campaign[edit]

Hoover was nominated by the Republicans for a second term. In his nine major radio addresses Hoover primarily defended his administration and his philosophy. He realized he would lose. The apologia approach did not allow Hoover to refute Franklin Roosevelt's charge that he was personally responsible for the depression. [7]

Bonus Army[edit]

Thousands of World War I veterans and their families demonstrated and camped out in Washington, D.C., during June 1932, calling for immediate payment of a bonus that had been promised by the Adjusted Service Certificate Law for payment in 1924. Although offered money by Congress to return home, some members of the "Bonus army" remained. Washington police attempted to remove the demonstrators from their camp, but they were unsuccessful and the conflict grew. Hoover sent U.S. Army forces led by General Douglas MacArthur and aided by junior officers Dwight D. Eisenhower and George S. Patton to stop a march. MacArthur, believing he was fighting a communist revolution, chose to clear out the camp with military force. In the ensuing clash, hundreds of civilians were injured and several were killed. The incident was another negative for Hoover in the 1932 election.

Administration and Cabinet[edit]

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM | ||||

| President | Herbert Hoover | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Vice President | Charles Curtis | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of State | Henry L. Stimson | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of the Treasury | Andrew Mellon | 1929–1932 | ||||

| Ogden L. Mills | 1932–1933 | |||||

| Secretary of War | James W. Good | 1929 | ||||

| Patrick J. Hurley | 1929–1933 | |||||

| Attorney General | William D. Mitchell | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Postmaster General | Walter F. Brown | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of the Navy | Charles F. Adams | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of the Interior | Ray L. Wilbur | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of Agriculture | Arthur M. Hyde | 1929–1933 | ||||

| Secretary of Commerce | Robert P. Lamont | 1929–1932 | ||||

| Roy D. Chapin | 1932–1933 | |||||

| Secretary of Labor | James J. Davis | 1929–1930 | ||||

| William N. Doak | 1930–1933 | |||||

Supreme Court appointments[edit]

Hoover appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Charles Evans Hughes (Chief Justice) – 1930

- Owen Josephus Roberts – 1930

- Benjamin Nathan Cardozo – 1932

Post-Presidency[edit]

His opponents in Congress, who, he felt, were sabotaging his program for their own political gain, portrayed him as a callous and cruel president.

Hoover was defeated in the 1932 presidential election by a landslide. After Roosevelt became the president, Hoover criticized the New Deal, and warned against statist tendencies. His concerns are written in the book, The Challenge to Liberty, where he talked of fascism, communism, and socialism as enemies of traditional American liberties.

In 1938, Hoover toured in Europe and met many European heads of states, including Adolf Hitler, the leader of Nazi Germany.

In 1940, Hoover spoke at the Philadelphia Republican convention. Numerous reporters, including Drew Pearson, wrote that Hoover was positioning himself for the nomination, which, although taking place as France fell to Hitler's armies, was split among four candidates, the isolationists (Thomas Dewey, Robert Taft and Arthur Vandenberg) and the eventual winner Wendell Willkie, who was an anti-Nazi. Hoover said that Hitler's victory over Europe was certain, and what America needed was a man as President who could do business with Hitler, and who had never alienated him. This is detailed in the Charles Peters book, "Five Days in Philadelphia."

After he left the White House in 1933, Hoover returned to Palo Alto, California. Despite repeated attempts to get back into politics, Hoover gained a greater reputation as a public servant. Hoover strongly opposed the Lend Lease program of military aid to Britain and any U.S. involvement in World War II.[8] After the war, and two years after the death of his wife, President Harry S. Truman asked Hoover to get involved in the world hunger issue. His appointment as Co-ordinator of Food Supply for World Famine mirrored his efforts in World War I but was broader in scope as it attempted to organize food distribution of all of Europe. He also refused any pay for the post, a demonstration of his humanitarianism and dedication. In 1947, Truman appointed him to head up a presidential commission (called the Hoover Commission on rationalizing the executive branch. The commission made many recommendation which Truman implemented. President Dwight Eisenhower appointed Hoover to a second Hoover Commission in 1953 for similar purposes.

Post World War II[edit]

Based on Hoover's previous experience with Germany at the end of World War I, in the winter of 1946 - 47 President Harry S. Truman selected Hoover to do a tour of Germany in order to ascertain the food status of the occupied nation. Hoover toured what was to become West Germany in Field Marshall Herman Goering's old train coach and produced a number of reports sharply critical of U.S. occupation policy. The economy of Germany had "sunk to the lowest level in a hundred years"[9]. As the Cold War deepened, Hoover expressed reservations about some of the activities of the American Friends Service Committee, which he had previously strongly supported.

In 1947, President Harry S. Truman appointed Hoover to a commission, which elected him chairman, to reorganize the executive departments. This became known as the Hoover Commission. He was appointed chairman of a similar commission by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. Both found numerous inefficiencies and ways to reduce waste.

Hoover died at the age of 90 in New York City at 11:35 a.m. on October 20, 1964, 31 years and seven months after leaving office. He had outlived his wife by 20 years. By the time of his death, he had rehabilitated his image. He had the longest retirement of any President. (Gerald Ford as of 2006 has been out of office for 29 years). Hoover and his wife are buried at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa. Hoover was honored with a state funeral, which was America's third in a span of 12 months following John F. Kennedy and Douglas MacArthur.

Heritage and memorials[edit]

The Lou Henry and Herbert Hoover House, built in 1919 in Palo Alto, California, is now the official residence of the president of Stanford University, and a National Historic Landmark. Hoover's rustic rural presidential retreat, Rapidan Camp (also later known as Camp Hoover) in the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, has recently been restored and opened to the public. The Hoover Dam was also named in his honor.

Quotes[edit]

- "True American Liberalism utterly denies the whole creed of socialism." [10]

- "A chicken in every pot and a car in every garage" - Presidential Campaign Slogan 1928

- "I outlived the bastards" - answer to a question of how he managed to survive the long ostracism under the Roosevelt administration. (Hoover also outlived every member of his own Cabinet, as well as the Harding and Coolidge Cabinets).

- "Once upon a time my political opponents honored me as possessing the fabulous intellectual and economic power by which I created a worldwide depression all by myself."

- "Older men declare war. But it is the youth that must fight and die."

- "There are only two occasions when Americans respect privacy, especially in Presidents. Those are prayer and fishing."

- "Wisdom oft times consists of knowing what to do next"

- "Democracy is a harsh employer." - Comment to a former secretary in 1936.

- "The only trouble with capitalism is capitalists - they are too damn greedy."

See also[edit]

- Fishing for Fun- and to Wash Your Soul

- U.S. presidential election, 1928

- U.S. presidential election, 1932

- Hoover-Minthorn House

- Hoover Institution

- Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum - located near Iowa City in West Branch, Iowa.

- Hooverball - sport created by Hoover's physician, played nearly every morning of his presidency on the White House lawn

- Herbert Hoover National Historical Site - also in West Branch, Iowa

- Rapidan Camp - Hoover's presidential retreat and fishing camp in Virginia

- Hooverville

Notes[edit]

- ↑ David M. Hart, "Herbert Hoover's Last Laugh: The Enduring Significance of the 'Associative State' in the United States," Journal of Policy History (MONTH?? 1998), PAGE NUMBERS??.

- ↑ Janet Hutchison, "Building for Babbitt: The State and the Suburban Home Ideal," Journal of Policy History (MONTH?? 1997), PAGE NUMBERS??.

- ↑ Roy V. Peel and Thomas C. Donnelly, The 1928 Campaign: An Analysis (Arno, 1931); Donald R. McCoy, "To the White House, Herbert Hoover, August 1927-March 1929, in Martin L. Fausold and George T. Mazuzan, eds., The Hoover Presidency: A Reappraisal (State University of New York Press, 1974).

- ↑ Britten, Thomas A. "Hoover and the Indians: the Case for Continuity in Federal Indian Policy, 1900-1933" Historian 1999 61(3): 518-538. Issn: 0018-2370

- ↑ Economists William D. Lastrapes and George Selgin, in "The Check Tax: Fiscal Folly and The Great Monetary Contraction" (Journal of Economic History 57, no. 4 [December 1997], 859-78), conclude that the check tax was "an important contributing factor to that period's severe monetary contraction."

- ↑ 1930s Engineering, Andrew J. Dunar on PBS.

- ↑ Carcasson, Martin. "Herbert Hoover and the Presidential Campaign of 1932: the Failure of Apologia" Presidential Studies Quarterly 1998 28(2): 349-365.

- ↑ Miller and Walch, p. 184

- ↑ Michael R. Beschloss, The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002) pg.277

- ↑ The Challenge to Liberty, pg 57.

KSF

KSF