History of Ireland

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

The History of Ireland is the topic of this article; for Ireland in the 21st century see Ireland (state) and Northern Ireland.

History[edit]

- Kingdom of Oriel - an ancient kingdom situated in southern and central Ulster.

Early Christian Ireland[edit]

This period has often been characterised as Ireland's golden age. With the coming of Christianity under Saint Patrick Ireland built many monasteries, made many documents (Such as the Book of Kells) and generally saw a period of peace and relative prosperity, in comparison to its European counterparts.

Middle Ages[edit]

In 1167 the deposed King of Leinster, Dermott Mc Murrough traveled to England to hire mercenaries in order to retake his Kingdom. With the consent of Henry II, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke (popularly known as Strongbow) arrived with a small army of Norman knights who proved vastly superior to their Irish counterparts. With their help, Mc Murrough regained his lands. De Clare married Mc Mourrough's daughter, and later laid claim to the crown of Leinster. Henry II, fearful of the possibility of a rival Norman state on his doorstep, arrived in Ireland in 1171 and secured nominal control of the island in 1175. This sequence of events ensured a foothold on the island for successive Anglo-Norman and British rulers, which eventually culminated in the plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

The most successful of these plantations was the Ulster Plantation. This colonisation effort was spearheaded by English and Scottish Protestants who took control of the lands confiscated by Irish Lords following the Flight of the Earls in 1607. These original Protestant colonists formed the basis of the Ulster-Scots culture which would find itself at odds with the Catholic Gaelic-Irish culture on the island.

1798-1900[edit]

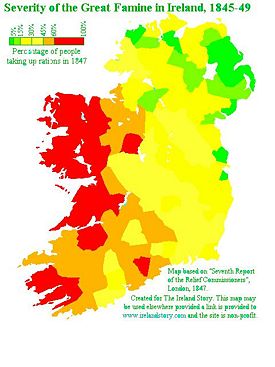

see also Irish Famine

The failed rebellion of 1798 created an atmosphere of sectarian distrust, which the union and the long delay in granting emancipation only reinforced. Daniel O'Connell's repeal agitation in the 1840s encouraged a fresh political polarization, as the coalition of O'Connellite Catholics, Belfast liberals, and British Whigs, which had been formed during the campaign for emancipation and remained active into the 1830s, could not be sustained when Catholics mobilized for a severance of the union.

The great famine of the 1840s, accompanied by accusations of genocide, left its own bitter legacy, while the immediate post-Famine decades were dominated not by a "League of North and South," united on the issue of tenant right, but by the recrudescence of the revolutionary tradition in the form of Fenianism. Similarly, the essentially conservative home rule movement, which sought to provide security for Irish Protestants and guarantees for British strategic interests, ultimately failed in the face of Unionist and Republican intransigence.

1900-1923[edit]

- Easter Rising

- Irish War of Independence

- Irish Civil War

- Ulster Unionism

- Northern Ireland

- Michael Collins

- Éamon de Valera

1923-68[edit]

see Éamon de Valera

The result of sectarian hatreds was a partition of Ireland, which reflected--imperfectly--the ethno-religious division within the island. Even as the Irish Free State and Republic adopted rhetoric of unification, the social, economic, cultural/linguistic, and foreign policies of the South between 1923 and 1968 introduced serious obstacles to a rapprochement with Northern Ireland, while the attitude of Northern Ireland's political leadership became harsher and less accommodating to the large Catholic minority.

1958-98[edit]

see Irish Troubles

After decades of endemic low-level violence and ill will, the "Good Friday agreement" of 10 April 1998, brokered by the U.S., produced a cease-fire that continues in operation. It was endorsed by most, but not all, political parties in Northern Ireland, and endorsed in referenda by majorities of voters in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. It created a new national Assembly with promises of equal treatment. Ireland renounced its historic claims to control the entire island.

Celtic Tiger: 1990 to 2008[edit]

After 1987 the nation began neoliberal economic policies that were agreed to by government, business, farmers' groups, trade unions and the community and voluntary sectors, in a programme known as "Social Partnership". Explosive economic growth followed, taking the nation past Britain and Germany by 2000, to the top of the EU in terms of prosperity. Dubbed in 1994 the "Celtic Tiger," the country with a population of 4.4 million became a magnet for immigrants from the EU and beyond.[1]

In the decade after 1995, Ireland's economic indicators all soared. Total output (GDP) went up by 350%, personal disposable income doubled, exports increased fivefold, trade surpluses mounted into the billions, employment skyrocketed. In 1995 Irish consumers spent £23 billion on goods and services, in 1999, £34 billion, and in 2000, £40 billion. However, since 2004 growth has slowed, because of rising wages and inflation, poor infrastructure (such as poor road and rail systems) and the addition of new lower-wage countries to the European Union.

Prosperity brought a surge of immigration. In 1990 fewer than 50 immigrants applied for asylum in Ireland; by 2001 the number had reached 11,000. By 2001, immigrants from Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Philippines, and Romania were pouring into the country and 36,000 work permits were issued.

Foster (2008) argues the cause was a combination of a new sense of initiative and the entry of American corporations such as Intel. He concludes the chief factors were low taxation, pro-business regulatory policies, and a young, tech-savvy workforce. For many multinationals the decision to do business in Ireland was made easier still by generous incentives from the Industrial Development Authority. EU membership was also helpful, giving the country lucrative access to markets that it had previously researched only through the United Kingdom, and pumping huge subsidies and investment capital into the Irish economy.

Modernisation brought secularisation in its wake. The traditionally high levels of religiosity have sharply declined. Foster (2008) points to three factors: Irish feminism, largely imported from America with liberal stances on contraception, abortion, and divorce undermined the authority of bishops and priests. Second, the mishandling of the pedophile scandals humiliated the Church, whose bishops seemed less concerned with the victims and more concerned with covering up for errant priests. Third, prosperity brought hedonism and materialism that undercut the ideals of saintly poverty.[2]

The worldwide economic downturn combined with fiscal policies that prompted a property boom then a bust brought the Celtic Tiger era to an end in 2008. In 2010, the Irish government had to resort to an EU and IMF "bailout".

References[edit]

- ↑ Benjamin Powell, "Economic Freedom and Growth: The Case of the Celtic Tiger," The Cato Journal, Vol. 22, 2003 online edition; Philippe M. Brillet, "Ireland and Japan - the Search for the Tiger." Irish Geography 2005 38(2): 225-232. Issn: 0075-0778 Fulltext: online

- ↑ See Foster (2008)

KSF

KSF