History of Northern Ireland

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

- For prior history see Ulster Unionism.

The history of the state of Northern Ireland begins after the Government of Ireland Act, 1920 installed a form of Home Rule in Ireland, separating jurisdiction in the island, with six counties in the north-east called Northern Ireland and the other twenty-six counties being governed by a Southern Ireland parliament. Southern Ireland was eventually to become the Republic of Ireland.

The Craigavon era (1921-1940)[edit]

While Edward Carson had led the Unionist movement throughout Ireland, his right hand man, Sir James Craig was more than able to take his place as leader of the Unionist movement in Northern Ireland. Craig acted as a broker between the Ulster Unionists and London in working out key details of the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. Craig helped reorganize the UVF as a separate unit to defend Northern Ireland against the IRA; this led to the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary in November 1920. In 1921 there were pitched battles with IRA insurgents supported by Collins in Dublin. In January 1921 the new government of Northern Ireland began operations with Craig as Prime Minister.[1] Craig was helped by a weak Nationalist opposition - the Republicans and their more moderate Nationalist colleagues had been divided on how to deal with the new entity, as they wanted reunion with the South and not union with the UK. By contrast the Unionists were united and won repeated large majorities in the parliament (winning forty, compared to twelve seats combined for Nationalist and Republican candidates. Craig saw his priorities as establishing the new state on firm foundations; defending it against its enemies, within (who were loyal to Dublin) and without (the Irish Free State); preventing his over-zealous supporters from taking the law into their own hands (which might destabilize the state and bring intervention from London); and keeping a watchful eye on London, where Lloyd George by the spring of 1921 was anxious to reach a compromise with Sinn Féin.

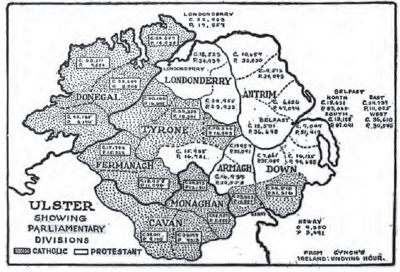

The Stormont parliament gerrymandered electoral districts in local councils to minimise Catholic representation. In 1929, the Unionists abolished the system of proportional representation set up by the British Parliament, and used the first past the post system used in Great Britain. The new system hit the smaller parties the hardest, with Labour and Independent Unionists losing four seats in the election.[2] When Eamon De Valera proclaimed Ireland was "a Catholic nation," Craig responded in 1934, that he stood for "a Protestant parliament and a Protestant state."[3] In 1937 Éire approved a new constitution that claimed sovereignty over the entire island.[4] With Éire claiming the entire island was rightfully theirs, Unionists were convinced that the Ulster Catholics were not loyal to King and country, and could not be trusted with responsibilities. Those Catholics who were elected to Stormont usually refused to take an oath of allegiance to the nation. Catholic protests at systematic discrimination in voting, housing and public resources formed the core of the civil rights movement in the 1960s. The historian of the Catholics asks, "how 'disloyal' were Catholics after partition?" and notes that Catholics who visibly supported the government were ostracized by other Catholics. She concludes, "It is certainly true that not until the 1960s were Catholics prepared to accept the legitimacy of the Northern Ireland state. But neither did they actively try to subvert it.... The bulk of northern Catholics remained, as they had always been, conservative, clerically-dominated, but utterly constitutional nationalists."[5]

James Craig served as Prime Minister for an unbroken period of nineteen years, making this period popularly known as the 'Craigavon era', as he later became 'Lord Craigavon'.

World War II[edit]

The Great depression was hard on the economy, with unemployment reaching 30%. In a total population of 1,280,000 (in 1937), regional unemployment was 72,000 in late 1940; it plunged to 19,000 (or 5%) by spring 1943. Full employment brought prosperity to all, and agriculture was mobilized for the war effort as well. In 1939 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain's proposed military conscription in Northern Ireland; he was blocked by a common front of the government in Dublin, northern nationalists, and the Catholic bishops - as well as by the apathy of the Unionist rank-and-file. By 1941, to reinforce ties with Westminster, to ease unemployment, and to conceal the low level of loyalist enlistments the Stormont government again requested conscription. Winston Churchill rejected the drafting of Irishmen, due to adamant opposition from Dublin and objections from the United States. However, volunteering for military service was enthusiastic among the Protestants.[6]

Northern Ireland was a vital strategic area of control for Britain during the war; its ports compensating for the loss of Éire's ports under the 1938 revised treaty. Americans soldiers made a major economic impact and social. German air raids in April and May, 1941, killed 1,110 people with over 2,000 injured; over 50,000 houses were hit damaged and 100,000 people made homeless.

Belfast, a vital industrial city, played a major role in the war providing ships, weapons, ammunition, army clothes, parachutes and a host of other equipment to the war effort. While Unionists in Northern Ireland were deeply and personally involved in the war effort, the Catholic communities were luke-warm at best.[7]

Politics was in turmoil during the war. Craig's death (in November 1940) led to the unfortunate choice of John Andrews (1871-1956), the minister of finance; he was indecisive and refused to purge the old ministerial "gang." The Andrews government collapsed in 1943 under mounting criticism that it was incompetent. The lack of preparation for the German air raids of April–May 1941 alarmed everyone; other grievances rose from its mishandling of the conscription question, its temporary suspension of Belfast corporation, the upsurge in labour strikes, and the inadequacy of its post-war planning. The aristocrat Basil Brooke became prime minister, serving 1943-1963.

1945-1969[edit]

After the war the departure of Éire from the Commonwealth in 1949 brought constitutional assurance that Northern Ireland would remain part of the UK as long as a majority there so wished. The new Labour government in London worked well with the conservative Unionists in Belfast, for the Unionist Party welcomed the increased spending on welfare (which helped further differentiate it from Éire. Renewed economic growth helped ensure that the 1950s and early 1960s were Northern Ireland's most harmonious and promising years; its post-war experience contrasted starkly with the relative stagnation and isolation of the south. Unionist confidence led to the willingness of some party members to consider reform, as the political system had long been notoriously corrupt and inefficient. Meanwhile, the voting behaviour of the Catholic minority, its increasing political activism, and the collapse of the IRA campaign of 1956–62 all suggested that Catholics were becoming more reconciled to permanent partition, but they were still angry at the restricted local government franchise, gerrymandering, religious discrimination by government and business, and the inadequacy of state funding for Catholic schools.[8]

Brooke's refusal to initiate fundamental reform was due in large part to his concern for Unionist unity. Regarding the Catholics, his strategy was based on the hope that welfare programs and sustained prosperity would eventually dissolve their nationalist aspirations. Brooke rejected those Liberal Unionists who sought to recruit Catholics into the Unionist Party. He retired in 1963.

notes[edit]

- ↑ It moved to the Stormont estate in 1932, and was often called the Stormont government.

- ↑ John Whyte, "How much discrimination was there under the unionist regime, 1921-68?" in Contemporary Irish Studies, edited by Tom Gallagher and James O'Connell (1983), online edition

- ↑ Boyce (2004)

- ↑ Article 2 said "The national territory consists of the whole island of Ireland;" article 3 claimed the "right of the Parliament and Government established by this Constitution to exercise jurisdiction over the whole of that territory." Article 9 added, "Fidelity to the nation and loyalty to the State are fundamental political duties of all citizens." See [1]

- ↑ Elliott, Catholics of Ulster (2001) p. 396

- ↑ Joseph L. Rosenberg, "Irish Conscription: 1941." Éire-ireland 1979 14(1): 16-25. Issn: 0013-2683

- ↑ Philip Ollerenshaw, "War, Industrial Mobilisation and Society in Northern Ireland, 1939-1945." Contemporary European History 2007 16(2): 169-197. Issn: 0960-7773

- ↑ Barton, "Brooke" 2004

KSF

KSF