Incunabulum

From Citizendium - Reading time: 2 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 2 min

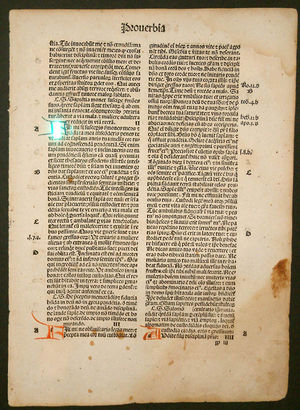

An incunabulum (plural incunabula; from the Latin for "in the cradle" or "swaddling clothes") is a European printed item (such as a book, a single sheet, or an image) produced before 1501. The term is sometimes Anglicised as "incunable".

The term was coined in the seventeenth century by book collectors to refer to the earliest printed European books. The first known use of the term is in a 1639[1] pamphlet by Bernhard von Mallinckrodt, De ortu et progressu artis typographicae ("Of the Rise and Progress of the Typographic Art") (Cologne) in the phrase "prima typographicæ incunabula" ("the first infancy of printing"). Von Mallinckrodt defined this infancy as ending in 1500, and his definition is still used, although it coincides with no change in printing techniques or technology.

The invention of metal-type printing is generally attributed to Johann (or Johannes) Gutenberg (c.1400–1468). Gutenberg's first printed book was a Bible, though it was not completely printed, as decorative work (illuminations) were added by hand. Nevertheless, printing increased the speed of production by eight times over that of manuscripts, making books much cheaper and more widely available.

Incunabula were originally almost indistinguishable from manuscripts, being designed in the same way: typefaces were essentially versions of handwriting, and varied from place to place; illuminations and rubrication; the use of columns; the use of contractions and abbreviations; the use of marginal notes. Only at thend of the incunabula period, in the 1480s, did the modern notion of a title page appear; before then, the book's title – or incipit – was followed immediately by the text. Details of the printing (the printer's name, the date and place, etc.) were either omitted or added at the end, in the colophon. (This latter fact often made it difficult to establish where an early printed work was in fact an incunabulum or not.)

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Roughly the bicentennary of the first printed book.

Sources and external links[edit]

- "An Introduction to Incunabula" by Phil Barber at www.historicpages.com

- "Incunabula: Dawn of Western Printing" — National Diet Library, Japan

- "Icunabula et cetera" — introduction from Psymon

- Incunabula collections at the British Museum

- The Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

KSF

KSF