Integral Fast Reactor

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

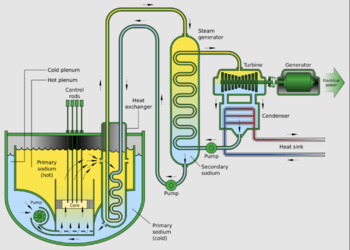

The Integral Fast Reactor (IFR) is Argonne Lab's best design,[1] a metal-fueled, sodium-cooled, pool-type [2] Fast Neutron Reactor, addressing all the issues raised in Nuclear_power_reconsidered (safety, waste management, weapons proliferation, and cost). "Integral" refers to the on-site reprocessing of the spent fuel. Some of the advanced reactor designs currently under development with venture capital are based on IFR/EBR-II technology -- GE's PRISM, Terrapower's Natrium, and ARC Clean Technology's ARC-100 reactor.

Choice of Fuel and Coolant[edit]

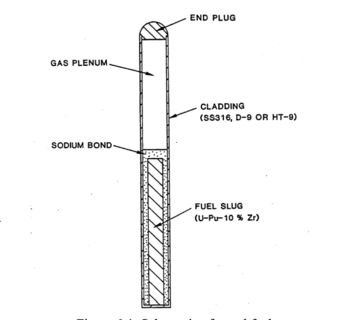

The IFR has a unique design for its fuel rods (Figure 1) that provides inherent safety, and also allows much higher fuel burnup than in conventional Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs). If the rods in an IFR overheat, the metal fuel inside the rod melts and flows into a non-reactive configuration, without any breach in the cladding. IFR rods are clad with strong steel, not the zirconium alloy used in PWRs to minimize neutron capture. Steel cladding will work in a reactor with fast neutrons like the IFR. To compare IFR metal fuel (uranium alloy) with PWR uranium oxide fuel (UO2), IFR fuel is "soft fuel, strong cladding" and PWR fuel is "hard fuel, weak cladding".

IFR safety is enhanced by the higher thermal expansion of metal fuel and sodium coolant, which provides strong negative reactivity feedback. If the fuel temperature rises, the fuel and coolant both expand, increasing neutron leakage from the core and thereby reducing the neutron chain reaction. In tech speak, the temperature to reactivity coefficient is negative -- the hallmark of a stable system.

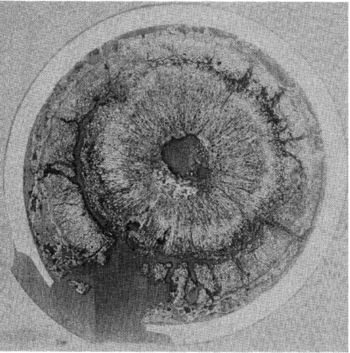

In standard PWR fuel rods, the low thermal conductivity of UO2 results in high fuel temperatures and swelling of the fuel from the buildup of fission gases trapped within the fuel. To avoid cladding failure due to fuel swelling and cracking, there is a gap filled with helium gas between the fuel and the cladding. If burnup is too high however, the swelling and cracking of the fuel can strain the cladding to failure. These problems have been addressed in PWR fuel rod designs, but maximum burnup is limited to typically 5-6% of the total energy in the fuel. (see Figure 3)

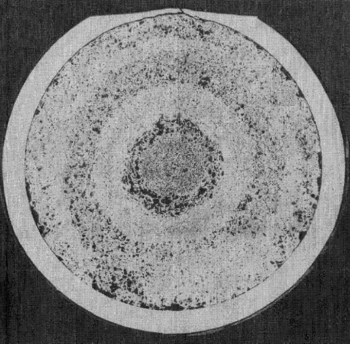

In IFR fuel rods, the fuel temperature and fission gas pressure are lower. Fission gases more readily escape the metal fuel, and accumulate in the plenum above the fuel, without unduly increasing the fuel rod internal pressure. As in PWR fuel, there is a gap between fuel and cladding, but the gap is filled with liquid metal sodium, which has much higher thermal conductivity than helium. Because metal fuel is softer than oxide fuel, mechanical contact with the cladding is less damaging, even after 12% burnup. (see Figure 4)

The zirconium cladding in PWR fuel rods show two chemical effects that are problematic. First, as happened at Fukushima, if the cladding temperature becomes too high in contact with water, the zirconium rapidly oxidizes, weakening the cladding and producing hydrogen gas. Second, in the event of a cladding breach, the oxide fuel reacts with water and releases fission products. Steel cladding does not suffer the rapid oxidation and hydrogen generation that zirconium does. If there is a cladding breach, fission products entering the sodium coolant are bound there rather than released.

See chapter 5 CHOOSING THE TECHNOLOGY in Till & Chang, 2011 for more on the choice of metal fuel and sodium coolant.

The Fuel Cycle[edit]

As in other fission reactors, the spent fuel is a mixture of uranium, trans-uranics, fission products, and fuel material diluents. In PWRs, recycling fuel material more than one time becomes impractical, but the IFR’s fast neutron spectrum makes repeated recycling entirely feasible.[6] The IFR fuel cycle chemistry, pyroprocessing, is optimum for civilian use -- good enough to recycle the materials into the reactor again, but not so selective as to make the recycled material attractive for diversion to a nuclear weapon. It uses electrochemical deposit of the recycle material on a cathode in a molten salt bath, rather like the re-deposit of lead on the electrode in a lead-acid battery.

The recycle system demonstrated at Argonne National Laboratory is a batch process that is expected to be substantially cheaper than aqueous reprocessing requiring miles of piping containing concentrated radioactive nitric acid.[7] Recycle facilities could economically service a cluster of IFR reactors co-located at one site.

Safety[edit]

The safety of the IFR design is ensured by several features:

1) The fuel and coolant expand if the temperature rises, providing strong negative reactivity feedback.

2) The metal fuel, a low melting point alloy of U-Pu-Zr, will melt if the rod ever gets too hot. The fuel then expands upward in the steel cladding, shutting down the fission reactions.[8]

3) Many of the fission products bind chemically with sodium, reducing the risk of fission product release if there is fuel failure.

4) Convection and thermal inertia in the large pool of molten sodium will easily handle the decay heat after a shut-down (see Figure 2).

5) The reactor vessel has no penetrations below the top of the pool, eliminating the possibility of sodium leakage.

6) A guard vessel provides double assurance that there will be no leaks to the room.[9]

7) There is no high pressure or water anywhere near the reactor vessel.

8) The space above the sodium pool and inside the guard vessel is filled with inert argon gas.[10]

Full-scale reactor tests were conducted at Argonne National Laboratory (West) in Idaho (now Idaho National Laboratory), in which the primary coolant pump was stopped with the reactor running at full power. All safety systems were disabled, and the control rods were held fully withdrawn. These "unprotected loss-of-flow tests" simulate the extreme scenario where all safety systems and operator actions have failed.

The chain reaction was terminated by core expansion, and the core was cooled by natural circulation, without fuel damage or radioactive leakage.[11] The IFR is "walk away safe".

Waste Management[edit]

- Fuel rods have an advantage over molten salt fuels in that the fission products are contained in the rod. This means a smaller volume of Spent Nuclear Fuel (SNF). Rods are easy to identify and count, which may be advantageous in preventing diversion.

- Fast neutron reactors have an advantage over moderated reactors in that higher fuel burnup means more energy for a given amount of spent fuel.

- Fast neutron reactors also burn most of the long-lived actinides that have led to worries about long-term disposal.

To compare waste flows for reactors of various types, we need to distinguish between Spent Nuclear Fuel (SNF) that goes to Interim Storage and High Level Waste (HLW) that must be permanently buried. To compare flows of fuel and waste for reactors of different sizes, we will normalize the numbers to grams per MegaWatt-day, and assume average power as 91% of rated maximum power.

A typical 1000 MWe PWR produces 22 tonnes per year of spent fuel assemblies (66 grams per MW-day).[12]

A ThorCon 500 MWe MSR should produce 13.43 tonnes of spent fuel salt per year (81 grams per MW-day).[13]

A 500 MWe IFR should produce 5 tonnes per year of heavy metal and fission product High Level Waste (30 grams per MW-day).[14]

Note: SNF from PWRs and MSRs can be reprocessed, and the final amount of HLW will depend on the details of that process.

Weapons Proliferation[edit]

The chemistry of the IFR fuel recycling process does not allow extraction of weapons-grade material at any point in the cycle. Many of the radioactive rare earth fission products stay in the recycled fuel material. This makes the material unattractive from a nuclear weapons material diversion standpoint -- it is too radioactive, contains non-fissile uranium, and is processed either in a highly radioactive argon-gas-atmosphere hot cell or as fully formed highly radioactive fuel elements. Further chemical separation and isotopic enrichment would be required, a situation not different in kind from starting with unprocessed fuel. So the IFR adds little or nothing to proliferation risk.[15]

In countries not licensed for fuel processing, return of the spent fuel to a secure location could be handled as for any other reactor with solid fuel rods. Rods are easy to count, and the number in transit at any one time can be small enough to avoid theft of a large quantity.

Cost[edit]

- No enormous pressure vessel with 7-inch steel walls.

- No huge containment building with 5-foot thick, steel reinforced, nuclear-grade concrete walls.

- No expensive safety systems to respond to accidents that happen only in PWRs.

- Metal fuel reprocessing is expected to be substantially cheaper than aqueous reprocessing of oxide fuels.

- Much lower uranium mining costs because essentially all of the uranium is consumed, rather than 0.6%.

Notes and References[edit]

- ↑ PLENTIFUL ENERGY The Story of the Integral Fast Reactor, Charles Till and Yoon Il Chang, 2011.

- ↑ The alternative "loop-type" is necessary in standard Pressurized Water Reactors. A low pressure coolant allows a larger "pool-type" reactor vessel capable of absorbing all the heat in an emergency shutdown. See Till & Chang, Section 5.4 The Reactor Configuration Choice.

- ↑ Schematic of the metal fuel rod. Fig.6.1 in Till & Chang, Chapter 6 IFR Fuel Characteristics.

- ↑ Oxide fuel (9% burnup) Fig.6.5 in Till & Chang, Chapter 6 IFR Fuel Characteristics.

- ↑ Metal fuel (12% burnup) Fig.6.6 in Till & Chang, Chapter 6 IFR Fuel Characteristics.

- ↑ Recycled fuel for moderated reactors like PWRs must have nearly all the fission products removed to minimize neutron absorption. Fast Neutron Reactors can tolerate much more impurity in the recycled fuel.

- ↑ The huge building containing reprocessing equipment at Hanford was nicknamed the "Queen Mary".

- ↑ Molten uranium is 10% less dense than solid (17.3 g/cc / 19.05 g/cc). The amount of expansion is actually greater than from melting alone. The fission gases trapped in the hot softened fuel cause it to expand into a spongy mass. This expansion can be as much as 20%. (see Section 7.10.1 in Till & Chang.)

- ↑ Unpressurized, a leak of sodium from the primary vessel would go into the space between the two vessels. That space is inerted with argon gas, and instrumentation is provided to monitor the space for any leaks into it. (There were none in the thirty-year lifetime of EBR-II.) Till & Chang, Section 5.4

- ↑ Sodium Reaction with Air and Water, Till & Chang, Section 7.12.

- ↑ Experimental Confirmations of Limited Damage in the Most Severe Accidents,Till & Chang, Section 7.10.

- ↑ add text with link here

- ↑ See the ThorCon Fuel Cylce diagram for calculated flows of fuel and spent fuel salt.

- ↑ add text with link here

- ↑ Nonproliferation Aspects of the IFR, Till & Chang, Chapter 12. "Assessments by weapons-development experts concluded that the electrorefining process is intrinsically proliferation-resistant and cannot be utilized to produce weapons- usable materials directly. [17, 19-22]"

KSF

KSF