Jacksonian Democracy

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

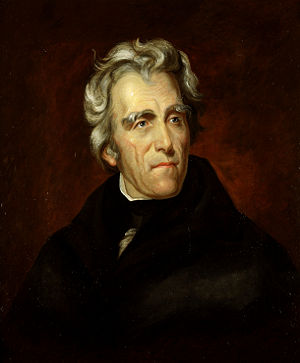

Andrew Jackson

Jacksonian Democracy was the political philosophy of the Second Party System in the United States in the 1820s to 1840s, especially the positions of President Andrew Jackson and his followers in the new Democratic Party. Jackson's policies followed in the footsteps of Jefferson. Jackson's Democratic Party was resisted by the rival Whig Party. More broadly, the term refers to the period of the Second Party System (1824-1854) when Jacksonian philosophy was ascendant as well as the spirit of that era. It can be contrasted with the characteristics of Jeffersonian Democracy, which dominated the First Party System. The Jacksonian era saw a great increase of respect and power for the common man; before the era began the electorate had already been expanded to include all white male adult citizens,[1] but now they exercised decisive political power. Turnout rose as new campaign techniques were used to mass the party-as-army at the polls on election day, with the victor getting the "spoils" of lucrative public office.

Broadly, Jacksonian democracy, in contrast to the Jeffersonian era, promoted the strength of the executive branch and the Presidency at the expense of Congressional power, while also seeking to broaden the public's participation in government. Jacksonians believed in enfranchising all white men, rather than just the propertied class, and supported the patronage system that enabled politicians to appoint their supporters into administrative offices, arguing it would reduce the power of elites and prevent aristocracies from emerging. They demanded elected (not appointed) judges and rewrote many state constitutions to reflect the new values. In national terms the Jacksonians favored geographical expansion, justifying it in terms of Manifest Destiny. There was usually a consensus among both Jacksonians and Whigs that battles over slavery should be avoided. The Jacksonian Era lasted roughly from Jackson's election until the slavery issue became dominant after 1850 and the American Civil War dramatically reshaped American politics and the Third Party System emerged. Historian Charles Sellers argued in The Market Revolution (1991)that the movement toward democracy was neutralized and overwhelmed by the coming of capitalism in what he called "The Market Revolution."

The philosophy[edit]

Jacksonian democracy generally was built on several principles:

- Expanded suffrage

- The Jacksonians believed that voting rights should be extended beyond landowners to include all white men of legal age. During the Jacksonian era, white male suffrage was dramatically expanded throughout the country.

- Manifest Destiny

- This was the belief that Americans had a destiny to settle the American West and to expand control over all of North America from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. The Free Soil Jacksonians, notably Martin Van Buren, however, argued for limitations on expansion to avoid the expansion of slavery within the Union. The Whigs generally opposed Manifest Destiny and expansion, saying the nation should build up its cities.

- Patronage

- Also known as the spoils system, patronage was the policy of placing political supporters into appointed offices. Many Jacksonians held the view that patronage was not only the right, but also the duty of winners in political contests. Patronage was theorized to be good because it would encourage political participation by the common man and because it would make a politician more accountable for poor government service by his appointees. Jacksonians also held that long tenure in the civil service was corrupting, so civil servants should be rotated out of office at regular intervals.

- Strict construction of the Constitution

- Like the Quids of Old Republican faction of the Democratic-Republicans who strongly believed in states rights and wanted to keep the federal government weak, Jacksonians initially favored a federal government of limited powers. Jackson said that he would guard against "all encroachments upon the legitimate sphere of State sovereignty". This is not to say that Jackson was a states' rights extremist; indeed, the Nullification Crisis would find Jackson fighting against what he perceived as state encroachments on the proper sphere of federal influence. This position was one basis for the Jacksonians' opposition to the Second National Bank. As the Jacksonians consolidated power, they more often advocated a more expansive construction of the Constitution and of Presidential power.

- Laissez-faire economics

- Complementing a strict construction of the Constitution, the Jacksonians generally favored a hands-off approach to the economy. The leader was William Leggett of the Loco-Focos in New York City. Jackson believed that when the government took a stronger role in the economy, it made it easier for favored groups to win special privileges, which was anathema to a nation run by, and for, the common man. In particular, the Jacksonians opposed banks, especially the national bank, known as the Second Bank of the United States.

The Market Revolution[edit]

In his The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 (1991), Charles Sellers argued that the greatest transformation in the American history of the first half of the nineteenth century—indeed, the defining event in world history—was a revolution from agrarian to capitalist society. He wrote, "Establishing capitalist hegemony over economy, politics, and culture, the market revolution created ourselves and most of the world we know." As broad and as audacious as this theory is, Daniel Walker Howe (2007) made three objections. First, Howe suggests that the market revolution happened much earlier, in the eighteenth century. Second, Howe claims that Sellers errs in emphasis arguing that because “most American family farmers welcomed the chance to buy and sell in larger markets,” no one was mourning the end of traditionalism and regretting the rise of modernity. The market revolution improved standards of living for most American farmers. For example, a mattress that cost fifty dollars in 1815 (which meant that almost no one owned one) cost five in 1848 (and everyone slept better). Finally, retorts Howe, the revolution that really mattered was the “communications revolution”: the invention of the telegraph, the expansion of the postal system, improvements in printing technology, and the growth of the newspaper, magazine, and book-publishing industries, and the improvements in higher-speed transportation.

In a debate with Sellers, Howe asked. "What if people really were benefiting in certain ways from the expansion of the market and its culture? What if they espoused middle-class tastes or evangelical religion or (even) Whig politics for rational and defensible reasons? What if the market was not an actor (as Sellers makes it) but a resource, an instrumentality, something created by human beings as a means to their ends?" However, Sellers summed up the differences between his and Howe’s arguments this way. Howe was proposing that the "Market delivers eager self-improvers from stifling Jacksonian barbarism" whereas he saw that a "Go-getter minority compels everybody else to play its competitive game of speedup and stretch-out or be run over."[2]

Politics[edit]

Election by the "common man"[edit]

John Quincy Adams was the first president ever to be partially elected by the common citizenry, as the 1824 Presidential election was the first in which all free white men without property could vote. Issues of social class have been much discussed by historians (Wilentz 1982).

The Anti-Masonic Party, an opponent of Jackson, introduced the national nominating conventions to select a party's presidential and vice presidential candidates, allowing more voter input.

Jackson, a hero of the War of 1812, was a rough-hewn, dueling frontiersman who rejected the norms of polite Eastern society.

Factions 1824–32[edit]

The period 1824–32 was politically chaotic. The Federalist Party was dead. With no effective opposition, the old Democratic-Republican Party withered away. Every state had numerous political factions, but they did not cross state lines. Political coalitions formed and dissolved, and politicians moved in and out of alliances.

Many former Democratic-Republicans supported Jackson; others, such as Henry Clay, opposed him. Most former Federalists, such as Daniel Webster, opposed Jackson, although some, like James Buchanan, supported him. In 1828, John Quincy Adams pulled together a network of factions called the National Republicans, but he was defeated by Jackson's coalition.

The system stabilized in 1832-34, as the National Republicans joined with other anti-Jacksonians, especially the Anti-Masonic Party, to form the Whig party. The Democrats and Whigs now battled it out nationally and in every state, with the Democrats have a slight edge before 1848, and after that a larger advantage so the Whigs seldom won.

Reforms[edit]

Jackson fulfilled his promise of broadening the influence of the citizenry in government, although not without controversy over his methods.

Jacksonian policies included ending the bank of the United States, expanding westward, and removing American Indians from the Southeast. Jackson was denounced as a tyrant by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. Jacksonian democracy had a lasting impact on allowing for more political participation from the average citizen, though Jacksonian democracy itself largely was taken over by the Copperheads and became the outsider faith, as practiced by William Jennings Bryan in the 1890s. The mainstream of politics, starting with the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln was the new Republican party.

Jacksonian democracy was blamed for the economic Panic of 1837, which ruined the presidency of Martin Van Buren and led to the Whig victory in 1840.

Jackson created a system to clear out elected officials in government of an opposing party and replace them with his supporters as a reward for their electioneering. With Congress controlled by his enemies Jackson relied heavily on the power of the veto to block their moves.

Jacksonian Presidents[edit]

Martin Van Buren, Jackson's second vice president and the key organizer of the Democratic party, followed Jackson to the White House. Because the Democrats took the blame for the nationwide economic depression that followed the Panic of 1837, Van Buren was ousted by Whig William H. Harrison in 1840 in a campaign marked by very high turnout nationwide. The Whigs learned they could appeal to the average (or above average) voter successfully. Harrison died just 30 days into his term, and his vice president, John Tyler was an ex-Democrat who was expelled by the Whig Party for abandoning its principles. Tyler was succeeded by James Polk, a staunch Jacksonian. After the Mexican War, both parties were troubled by the slavery issue, and the Whigs collapsed in 1852 and vanished by 1854. They were replaced in the North by the new Republican party, formed in 1854.

Primary sources[edit]

- Blau, Joseph L. Social Theories of Jacksonian Democracy: Representative Writings of the Period 1825-1850 (1954) online edition

- Eaton, Clement ed. The Leaven of Democracy: The Growth of the Democratic Spirit in the Time of Jackson (1963) online edition

- Register of Debates in Congress, 1824-37; complete text; searchable

- Daniel Webster

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Except in Rhode Island, which had a revolt called the Dorr War against franchise restrictions.

- ↑ This review of the Sellers/Howe dialogue, which goes back to at least 1994, is from Jill Lepore, "Vast Designs: How America Came of Age," New Yorker, October 29, 2007; see p. 88 for quotations.

KSF

KSF