Mechane

From Citizendium - Reading time: 6 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 6 min

A mêchanê (μηχανῆ, plural: mêchanaí)[1] was a lifting and slewing crane used in ancient Greek and Roman theater and was probably in wide use since the early fourth century BC. The device was used to lift harnessed actors, animals (e.g. horses) and theatrical props like chariots into the air from or onto the stage from behind the skene, whenever the plot required a character or a prop to fly. The stage machine was later used to also bring gods onto the stage from above,[2] hence the Latin term deus ex machina ("god from the machine").[3]

Extant sources[edit]

Archaeological evidence[edit]

None of the ancient mêchanaí have been preserved, and circumstantial evidence is scarce. Mythological characters depicted in flight on Greek vases are shown without the mêchanê, which indicates that the crane was also not very visible in the theatrical context. This is in accordance with Greek aesthetics, since a highly visible theater mechanism would not be in tune with the scenery, costumes and masks. At least four vases are known that depict mêchanê-scenes from ancient Greek theater plays, among them impressions of Medea from Euripides' play of the same name, of Bellerophon from Euripides' Stheneboea or Bellerophon, of Sarpedon (most probably from Aeschylus' play Europa) and of a scene probably based on Rinthon's comedy Heracles, which shows Heracles and Zeus, who threaten Apollo with a thunderbolt and a club. Since Apollo is seated on a scaffold, which is slightly out of place, the scaffold could be the only conserved depiction of an ancient mêchanê, alas as a caricature.

Literary sources[edit]

later

Construction and operation[edit]

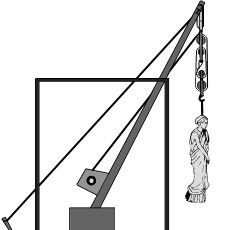

© VRoma (by permission)

The mechane does not appear to have any close predecessor and its development is of great engineering significance since it appears that it was designed to meet very close requirements of the play and it was not arrived at by long evolution.[5] Since the mêchanê had to carry weights of up to one ton, the device was probably supported by the projection of stone which extended into the orchestra from the terrace wall, and was affixed to one of the posts which supported the skene.[6] When not in use it was hidden behind the upper level of the skene.[7] The mêchanê itself consisted of wooden beams and a pulley system, i.e. wheels and ropes which could raise considerable weights and, in some cases, violently pan or move them back and forth, when the play demanded it. The vertical dimensions were over four meters, while the horizontal travel could be more than eight meters.[8] The mêchanaí must have been well-balanced with sufficient counter-weights and were operated by the theater's engineer, the so-called mêchanopóios, a term also used for the designer and builder of the mêchanê. The crucial dramatic timing between stage and engineering can in theory be deduced from specific lines sung by the choros, which hint at the amount of time that the engineers were granted to unload, reload or operate the mêchanê.

Original dramatic use[edit]

Euripides[edit]

© VRoma (Used by permission)

Euripides' use of the mêchanê in Medea (431 BC) is a notable early application of the machine for a non-divine character, providing a means of escape for Medea from Corinth after she murders her children. It was used by Euripides to counter the reality of domestic murder featured at stage level, elevating Medea to godhead. The mechanical ascension possibly symbolized the underestimated power of her evilness and fury.[9] In his play The Bacchae Euripides however used the theater machine in a purely divine manner from the outset to present Dionysus as his own deus ex machina, first by introducing him as a god disguised as a man, then revealing him in an epiphany at the end of the play, reintroduced to the stage by use of the mêchanê.[10] Euripides' concluding use of the device became his infamous trademark, which he also applied in more venturesome ways, as e.g. shown in the hero's ascension on a Pegasus in his lost play Bellerophon.[11]

Other Greek authors[edit]

The earliest known use of the mêchanê is possibly found in The Eumenides by Aeschylus, who utilized several theatrical devices for the staging of his tragedy, including a theater machine, on which he placed the gods Apollo and Europa. Evidence is however unclear, because the use of the mêchanê could have been added as a stage direction at a later date, when the theater machine became widely available.[12] Sophocles in his old age utilized the mêchanê to introduce Heracles at the end of Philoctetes to induce the title character to leave for Troy. The mêchanê was used in tragedies and comedies alike, a representative for the latter being Aristophanes, who was all-too happy to parody Euripides' notorious use of the theater machine, e.g. in Peace, where the peasant hero, in an blatant take on Euripides' Pegasus-exit, embarks on a hazardous, heavenward stage flight, riding a giant dung beetle and shouting: "Crane-driver, take good care of me!"

Other[edit]

© VRoma (Used by permission)

Ancient Rome[edit]

Stage machines were also used in ancient Rome, not only in the theater but also e.g. during the sometimes highly dramatic performances at funerals. At least one instance is known: for Julius Caesar's funeral service Appian reports a rotating mêchanê that was used to present a blood-stained wax effigy of the deceased dictator to the funeral crowd.[13] Geoffrey Sumi proposed that the use of the mêchanê "hinted at Caesar's divinity".[14] This is highly unlikely because Appian doesn't describe the mêchanê as a genuine deus-ex-machina device: it clearly doesn't resemble any characteristics of a theater crane. Furthermore Caesar's apotheosis wasn't legally conducted until 42 BC, and Caesar had only been worshipped inofficially as divus during his lifetime. First and foremost Mark Antony, who functioned as choregós and probably as master of ceremonies during the funeral, attempted to arouse the masses as a means to strengthen Caesar's esteem as well as his own political power.[15]

Christianity[edit]

In Christian liturgy the mêchanê has been identified with the cross. Ignatius called the cross the "theater machine" of Jesus Christ.[16] The theatrical character of the Christian cross is still visible in the slanted suppedaneum ("footrest") of the original Crux Orthodoxa, which indicates the rotating movement of the cross that had been very prominent in depictions of the Christ's crucifixion, especially in the Orthodox Church, but also in the Western Church until the early Gothic period, e.g. on the famous Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, where the rotational attribute of the cross originates from the Christ's right arm being behind the hasta and the rotated lower part of the hasta including the suppedaneum turned to the side. The theatrical depictions of the cross could have originated in the traditional arma Christi processions and the paradoxical presentation of the cross as a tropaeum, a victory cross, during the Holy Week, especially on Good Friday.[17]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The word was first used by Homer in his Iliad to describe political manipulation. Later the word generally meant a "machine", more precisely a machine element meaning an assemblage of machines. The English word mechanism is a derivate. Aristophanes used the alternative term mêchanêma.

- ↑ Plato, Cratylus 425d; Clitophon 407a

- ↑ The mêchanê as a means for introducing a deus or a dea ex machina onto the stage was probably not in widespread use before the 4th century BC: "Gods who intervene in fifth century tragedies probably appeared through a trap-door on the roof of the skene to address mortals from a higher level." (Roger Dunkle, Introduction to Greek Tragedy)

- ↑ Loading cranes and theater mêchanai probably used a similar technology.

- ↑ Thomas G. Chondros, "Deus Ex Machina": Reconstruction and Dynamics, Patras 2004

- ↑ "Introduction to Greek Stagecraft", in Didaskalia, Berkeley 2002

- ↑ Edwin Wilson & Alvin Goldfarb, Living Theatre: A History, McGraw-Hill 2003, p. 50 sq.

- ↑ Dimarogonas, "Mechanics of the Ancient Greek Theater", ASME Design Conference, Phoenix 1992, quoted here (including reconstructional images).

- ↑ Maurice P. Cunningham, "Medea Aπο Mηχανης", in Classical Philology, Vol. 49, No. 3, 1954, pp. 151–160

- ↑ Reconstructed ending: J. Michael Walton, Greek Sense of Theatre: Tragedy Reviewed, Amsterdam 1939, p. 128

- ↑ Harold C. Baldry, "Theatre and society in Greek and Roman antiquity", in: James Redmond (ed.), Drama and Society (Themes in Drama Series 1), Cambridge 1979, p. 8

- ↑ U. Wilamowitz-Möllendorf, Einleitung in der Griechischen Tragödie, Berlin 1907

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 2.147: τὸ μὲν γὰρ σῶμα, ὡς ὕπτιον ἐπὶ λέχους, οὐχ ἑωρᾶτο. τὸ δὲ ἀνδρείκελον ἐκ μηχανῆς ἐπεστρέφετο πάντῃ. Appian's mêchanê probably describes the device (or part of the device) that Suetonius rendered as the tropaeum, which was covered by Caesar's blood-stained robe and to which possibly also the effigy (simulacrum) was affixed. (Divus Iulius 84; here tropaeum has been erroneously translated as "pillar".)

- ↑ Geoffrey S. Sumi, Ceremony and Power. Performing Politics in Rome between Republic and Empire, Ann Arbor 2005, pp. 107–109, chapter: "Caesar ex machina", ISBN 978-0-472-11517-4

- ↑ The fact that Caesar's resurrectio as god was believed to have happened later during the funeral as he was cremated, and that it spawned the early Caesarian cult by the Pseudo-Marius, can't explain Antony's intentions for using a mêchanê during the funeral, since the cremation occurred after the fact.

- ↑ Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians IX 1: ἀναφερόμενοι εἰς τὰ ὕψη διὰ τῆς μηχανῆς Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, ὅς ἐστιν σταυρός.

- ↑ Cf. Venantius Fortunatus, Pange Lingua

KSF

KSF