Note (music)

From Citizendium - Reading time: 12 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 12 min

In music, a note is an abstract representation of the pitch and duration of a tone. The pitch designated by a note is objective only in the case of a simple tone (also called a pure tone) such as produced by a tuning fork, which consists of only a single frequency of vibration, in which case the pitch is uniquely related to that frequency at a given loudness.[1]

Frequencies of various pure tones. The various A-notes are a factor of two apart in frequency, an octave (eight notes).[2] The number following a letter designation, as in A4, refers to the number assigned to the pertinent octave. The MIDI pitch numbers are explained later.

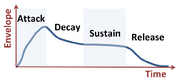

The amplitude of a musical note varies in time according to its sound envelope.[3]

A musical instrument on the other hand, produces a tone, which is a superposition of various frequencies with various amplitudes and phases peculiar to the instrument, and which also is affected by the manner of play that determines the sound envelope of the note (referred to by Lamb below as "adventitious circumstances").

Pitch is one of several perceived attributes of a tone. A laboratory determination of pitch is made by a subject listening to a tone from a musical instrument and to a simple tone, such as that produced by a tuning fork, and identifying circumstances where the instrument and the simple tone sound alike.[4] As a result, for other than simple tones, pitch is not a purely objective physical property; it is a subjective psychoacoustical attribute of a sound.

To quote Lamb:[5]

- One musical note may differ from another in respect of pitch, quality, and loudness. The pitch is usually estimated as that of the first simple-harmonic vibration in the series, viz. that of lowest frequency, but if the amplitude of this first component be relatively small, and especially if it fall near the lower limit of the audible scale, the estimated pitch may be that of the second component.

- By "quality" is meant that unmistakable character which distinguishes a note on one instrument from the note of same pitch as given by another...difference of quality, so far as it is not due to adventitious circumstances,† can only be ascribed to differences of vibration-form, and so to differences in the relative amplitude and phases of the simple-harmonic constituents.

- †Such as the manner in which the sound sets in and ceases; this is different for instance in the violin and the piano.

What Lamb refers to as "quality" of a note also is referred to as the timbre of a tone, that is, the subjective perceived quality of a tone that distinguishes different voices. The tone itself is objectively described by the measured frequency and phase of each constituent of its vibrational spectrum.

Tuning[edit]

In music, tuning is a scheme or temperament for selecting the pitches of available notes, and the process of setting up an instrument to play those notes. The term "temperament" is derived from tempering, which refers to small adjustments in pitch that make an interval smaller or wider, making the pitch ratio depart from a so-called pure interval that is defined as a ratio of small integers. (For example, 3:2 is a pure fifth, 4:3 a fourth, 5:4 a major third, 6:5 a minor third, and so forth.)[6]

Western music is based upon twelve pitches, while Arabic-Persian music often is said to use twenty-four.[7] Originally, the separation of pure tones corresponding to these pitches in Western music was governed by frequency ratios involving small integers like 2:1 (octave), 3:2 (fifth), and so forth (so-called pure intervals), culminating in the 16th century with the so-called mean-tone temperament.[8] However, from about the time of Johann Sebastian Bach, this variable separation slowly was replaced by the equal temperament in which the ratio of the frequencies of pure tones corresponding to successive notes is the twelfth root of 2. Each step in pitch is called a semitone or half tone. This approach allows smooth and rapid changes of musical key, and a melody sounds as though it uses the same intervals regardless of the note it begins with.[9] The switch to equal temperament met with resistance when it was introduced, because it sounded inharmonious to listeners of the older system.[10][11]

Comparison of even tempered notes with harmonics of C2. Column MIDI is the MIDI note number, and column n is the fractional "MIDI number" calculated using the frequency of the harmonic in the log2-formula found below.

From a physics standpoint, equal temperament is a compromise forced upon us by keyboard instruments that do not have the flexibility in pitch selection available to a violin, trombone, or to a singer.[12] When an instrument plays a note, in most cases a tone is produced with not only the fundamental frequency of the pure tone, but multiples of it. (The ratchet may be an exception, where pitch is set by the rate of rotation and not by a vibration, possibly introducing additional frequencies.) In the interest of harmony, one would like other notes on the instrument to match these frequencies, but that cannot be done on a keyboard instrument with fixed pitch separations.[13] The figure at left compares the notes based upon an even-tempered tuning that are closest in frequency to the harmonics (overtones) of the note C2. It can be seen that some higher frequency overtones are not matched closely by an even-tempered note. For example, the 11'th harmonic of C2 (the overtone at 11 times the frequency of C2) sits midway between F5 and G5♭. (Compare with Duffin, Figure 1, p. 22.[13]) The right column shows the difference in cents.

According to Ellis, when two notes are played together, a difference of 2 cents is noticeable, and a difference of 5 cents is heard as out of tune.[14] Observations indicate errors in playing a note of 5-15 cents are common, with errors of 20-50 cents above A7 (the 7th octave, 3 octaves above the octave containing middle C). The increased error at higher pitch was traced to a systematic error in the response of auditory nerves in the ear.[15]

From a performance standpoint, music written for mean-tone temperament (as reintroduced, for example, by the early music movement) sounds quite different than when played using instruments tuned using equal temperament.[16] It is said that "Listening to Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier in equal temperament is like looking at a Rembrandt under waxed paper."[17] A less picturesque assessment can be found in Kirkpatrick.[18] The basic idea is that well-temperament is an unequal temperament, retaining the basic characteristics of the earlier meantone system that avoids equivalent treatment of certain sharps and flats as is found in the equal temperament system.[19]

From a compositional standpoint, equal temperament is somewhat of a straightjacket.[20]

Notation[edit]

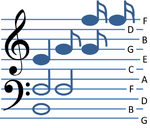

Musical clefs and notes of various durations arranged on the grand staff of eleven lines.

Pitch[edit]

In Western musical notation, the pitch of a sound is indicated by the vertical position of the symbol for the note on a staff or stave, an array of parallel leger lines (from the French leger=light), as shown in the figure. Certain lines on the staff are identified by clefs. For example, in the figure the upper clef is called the treble or G-clef, and the lower clef is called the bass or F-clef.[21]

The names of the notes correspond to the first seven letters of the alphabet, applied to both lines and spaces. The labeling associated with the lines on the staff is indicated, and the labels for the spaces follow alphabetically.[22] Men's voices are considered to range from lower G on the bass staff (the bottom five lines), through the next G in the tenor staff, to the third G in the in the alto staff. Women's and boy's voices range an octave higher, running up to the next G in the treble staff. See Jones,[21] §24, p.9. For voice exercises, the first note C on the so-called natural scale or scale of C is called doh and the notes of the first octave are named by the syllables doh (do), ray (re), me (mi), fah (fa), soh (sol), lah (la), te (ti), doh (do).[23]

Pure tones separated by an octave on the staff (that is, a combination of eight lines and spaces on the staff) are a factor of two different in frequency. The pitch denoted by a position on the staff is set by the key of the musical piece, indicated by a key signature. The key determines how many steps in pitch, or semitones, separate each of the notes within an octave. For example, indicating the number of semitones in parentheses, the C-major key is in the form C-D(2), D-E(2), E-F(1), F-G(2), G-A(2), A-B(2), B-C(1). The pattern repeats in each octave. The key signature is a series of sharp or flat symbols placed on the staff, designating notes that must be played one semitone higher or lower than the equivalent natural notes of the unmarked staff in order to realize the key. Particular chords (notes played together) are associated with each key.[24]

On the twelve semitone scale, also called the chromatic scale, and which corresponds with the keys of the grand piano, a pitch between C and D, say, is called C-sharp (denoted C♯) and is a semitone above C, or labeled D-flat (denoted D♭), a semitone below D. A complete cycle of notes on this scale is A, (A♯, B♭), B, C, (C♯, D♭), D, (D♯, E♭), E, F, (F♯, G♭), G, (G♯, A♭), A, and so on.[25]

The left-to-right position of the notes on the staff indicate the order in which they are played, the later notes further to the right, with notes directly above one another played simultaneously.

Duration[edit]

Some elements of musical notation.

Duration of a note is indicated by its symbol. Examples are shown in the upper figure of this article section, with the longest or whole note at the bottom, and the two half notes above it that combine to the same duration. The quarter note, eighth notes and sixteenth notes are successively stacked above.[22]

As shown to the right, the relative duration of a whole note is established by dividing the horizontal length of the staff into measures, bounded by vertical bars, and a time signature that determines how many "beats" occur in a measure, and which note corresponds to a beat. For example, the 4/4 time signature indicates common time or four beats to a measure (top number), with a quarter note one beat (bottom number); accordingly, a half-note has two beats, a whole note four beats, and so forth.[26]

Musical notation does not assign absolute duration to a beat.[27] Tempo indications, like presto and allegro, provide further guidance for pace.[28]

Loudness[edit]

Loudness in musical notation is indicated by written dynamic markings:

ƒƒƒ fortississimo or forte fortissimo extremely loud ƒƒ fortissimo very loud ƒ forte loud mƒ mezzo forte medium loud mp mezzo piano medium soft p piano soft pp pianissimo very soft ppp pianississimo or piano pianissimo extremely soft

An increase in loudness is indicated as crescendo, a decrease as decrescendo or diminuendo. Indication of one note louder than another is indicated by accents or articulation markings.[29] These are variously indicated by overscores above the note of ^, ^ for louder and much louder notes,[30] or by an overscore of > indicating a louder note but with weaker attack than suggested by ^.[31]

Digital representation of notes[edit]

There are various schemes for encoding music in a digital format. An early version, and perhaps most widespread, is the Musical Instrument Digital Interface or MIDI.[32] A later and more complete scheme is Csound.[33] Next, some detail is supplied about MIDI.

A MIDI file is the digital equivalent of sheet music, but goes much farther in detailing many aspects of play.[34] In this system, each note is assigned a numeric value with A4 (440 Hz; the A above middle C) given the number 69. The general formula for finding the frequency f of the pure tone associated with the pitch corresponding to a MIDI number n (an integer between 1 and 128 = 27) is:[35]

which means notes with adjacent MIDI numbers have frequencies in the ratio of 21/12, corresponding to tuning using the equal temperament mentioned earlier.[11] The above formula inverts to provide MIDI pitch number as:[36]

which is meaningful only for frequencies resulting in integer values of n in the range 1 - 128. Here log2 is the logarithm of its argument to the base 2. With these formulas, middle C with MIDI number 60 (C4) is assigned the frequency 261.6256... Hz.

There are 128 = 27 numbers available for digital assignment, many more than the 88 keys of a piano, so many more pitches are possible.[37] The grand piano keyboard (including sharps and flats) corresponds to MIDI numbers 21 - 108 or 27.5 Hz - 4,186 Hz, and the MIDI pitch numbers are shown for the A’s of the grand-piano keyboard in the figure in the Introduction.

The MIDI protocol sends messages that include aspects of pitch, timbre, and timing that allow a music synthesizer to imitate a piece of music played upon one instrument, or even several different instruments, in a predictable fashion.[32] Instructions designated Note-On and Note-Off specify the duration, loudness and pitch of a note. The timbre of a tone is selected by a MIDI Program Change message, consisting of a status byte and a data byte. The data byte identifies a patch number, for example, patch 20 may be a church organ and 106 a banjo on MIDI-compatible synthesizers.[38] Not all synthesizers, however, will associate the same patch number with the same instrument.[39] Control change or CC messages varying with the synthesizer select a particular bank of patches stored in the synthesizer, with each bank containing up to 128 patches.[40]

The MIDI protocol also includes coding to control an envelope generator, usually a part of the synthesizer. In particular, the MIDI protocol includes specific CC messages that specify the attack and release time constants (rise time and fall time) of the sound envelope shown above.[41]

References[edit]

- ↑ The pitch of pure tones varies somewhat with sound level, perhaps by as much as 5% and varying with the individual listener. Susan Hallam, Ian Cross, Michael Thaut (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology. Oxford University Press, p. 50. ISBN 0199604975.

- ↑ Based on data from Leon Gunther (2011). “Figure 11.2: Piano keyboard”, The Physics of Music and Color. Springer, p. 357. ISBN 1461405564.

- ↑ Stanley R. Alten (2010). “Sound envelope”, Audio in Media, 12th ed. Cengage Learning, p. 13. ISBN 049557239X.

- ↑ Thomas D. Rossing (2007). Springer Handbook of Acoustics. Springer, p. 477. ISBN 0387304460.

- ↑ Horace Lamb (2004). The Dynamical Theory Of Sound, Reprint of 1925 Edwin Arnold Ltd. 2nd ed. Courier Dover, p. 4. ISBN 048643916X.

- ↑ Thomas Donahue (2005). A Guide to Musical Temperament. Scarecrow Press, p. 63. ISBN 0810854384.

- ↑ In Arabic-Persian music, twenty-four quarter-tones are used instead of twelve half-tones. See Dorothea E. Hast, James R. Cowdery, Stanley Arnold Scott (1999). “The notes of Arabic music”, Exploring the World of Music: An Introduction to Music from a World Music Perspective. Kendall Hunt, pp. 125 ff. ISBN 0787271543. Some Western music has been written in this vein as well, for example, Charles Ives' Three quarter-tone pieces for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart.

- ↑ A description of the mean-tone temperament is found in “Mean-tone temperament”, Don Michael Randel, ed: The Harvard Dictionary of Music, 4rt ed. Harvard University Press, p. 496. ISBN 0674011635. An extended historical discussion of various tuning schemes is found in J. Murray Barbour (2004). Tuning and Temperament: A Historical Survey, Reprint of Michigan State College Press 1953 ed. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486434060.

- ↑ Joseph Rothstein (1994). “Pitch relationships in music”, Midi: A Comprehensive Introduction, 2nd ed. A-R Editions, Inc., pp. 27 ff. ISBN 0895793091.

- ↑ Ardal Powell (2002). “Equal temperament, a boxed highlight”, The Flute. Yale University Press, p. 148. ISBN 0300094981.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 For background on the shift to equal temperament, see Ross W. Duffin (2008). How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care). WW Norton & Co. ISBN 0393334201.

- ↑ Saeed V. Vaseghi (2007). Multimedia Signal Processing: Theory and Applications in Speech, Music and Communications. John Wiley & Sons, p. 422. ISBN 0470062010.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 For a discussion see Ross W. Duffin (2008). How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (and Why You Should Care). WW Norton & Co, pp. 20 ff. ISBN 0393334201. “The reason these simple intervals are in such simple ratios to one another is because they are part of the acoustical phenomenon called the harmonic series, or overtone series.”

- ↑ Alexander J Ellis (March 25, 1885). "On the musical scales of various nations; §III.–Cents". Journal of the Society of Arts 33: p. 487.

- ↑ See Figure 1 in Ohgushi, K and Ano, Y (2005). "The Relationship between Musical Pitch and Temporal Responses of the Auditory Nerve Fibers". Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applied Human Science 24 (1): pp. 99-101.

- ↑ Michael Chanan (1994). Musica Practica: The Social Practice of Western Music from Gregorian Chant to Postmodernism. Verso, p. 216. ISBN 1859840051. “Played in a modern transcription on modern instruments, the most poignant dissonances and chromatics easily become either bland or cloying.”

- ↑ Kyle Gann as quoted by Anthony Osborne (2006). Keyboard Connections: Proportion And Temperament in Music And Architecture. Equal Temperament, the Golden Section And a Few Other Mysteries. AuthorHouse, p. 36. ISBN 142084783X.

- ↑ Ralph Kirkpatrick (1987). Interpreting Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier: A Performer's Discourse of Method. Yale University Press, p. 6. ISBN 0300038933.

- ↑ Judith K. Linder Schneider (2004). “About the Well-Tempered Clavier, Volume II”, Judith K. Linder Schneider, ed: Bach – The Well-Tempered Clavier. Alfred Music Publishing, p. 4. ISBN 0739000047.

- ↑ Ben Johnston (2006). "Maximum Clarity" and Other Writings on Music. University of Illinois Press, pp. 63 ff. ISBN 0252030982. “...impoverished the logic of harmony and tonality by weakening the perceptibility of consonance and dissonance.”

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 F Leslie Jones (1874). “Chapter II: Musical notation”, A manual of the elements of vocal music. Oxford University Press, pp. 7 ff.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 John Taylor (1876). “Appendix B: Notation”, The student's text-book of the science of music. George Philip and Son, pp. 88 ff.

- ↑ The assignment of names for notes (called solmization) is more complicated than one might expect, and has an extended history and various schools of practice. See Steven M. Demorest (2003). Building Choral Excellence: Teaching Sight-Singing in the Choral Rehearsal. Oxford University Press, pp. 46 ff. ISBN 0195165500.

- ↑ E Bigand and B Tillmann (2005). “See discussion surrounding Figure 9.3: Tones chords and keys”, Christopher J. Plack, Andrew J. Oxenham, Richard R. Fay, eds: Pitch: Neural Coding And Perception. Birkhäuser, pp. 313 ff. ISBN 0387234721.

- ↑ The chromatic scale is only one of many scales. See, for example, (2003) “Scale degrees”, Don Michael Randel, ed: The Harvard Dictionary of Music, 4rth ed. Harvard University Press, p. 758. ISBN 0674011635.

- ↑ Michael Pilhofer, Holly Day (2111). “Introducing time signatures”, Music Theory For Dummies, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, pp. 37 ff. ISBN 1118169263.

- ↑ Nancy Scoggin (2010). Barron's AP Music Theory. Barron's Educational Series; Pap/Com edition, p. 15. ISBN 0764196316.

- ↑ Sandra P. Rosenblum (1991). “Chapter 9: Choice of tempo”, Performance Practices in Classic Piano Music: Their Principles and Applications. Indiana University Press, pp. 305 ff. ISBN 0253206804.

- ↑ H Fastl and M Florentine (2010). “§8.3.3 Language of loudness for music (musical notation)”, Mary Florentine, ed: Loudness, pp. 205 ff. ISBN 1441967117.

- ↑ Adela Harriet Sophia (Bagot) Wodehouse (1889). A Dictionary of Music and Musicians (A.D. 1450-1880) by Eminent Writers, English and Foreign, Volume 4. Macmillan, p. 120.

- ↑ David Fuller (2003). “Scale degrees”, Don Michael Randel, ed: The Harvard Dictionary of Music, 4rth ed. Harvard University Press, p. 3. ISBN 0674011635.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 An accessible overview of the MIDI protocol can be found in Walter B Hewitt, Eleanor Selfridge-Field, et al. (1997). “Chapter 2.1 What is MIDI?”, Eleanor Selfridge-Field, ed: Beyond Midi: The Handbook of Musical Codes. MIT Press, pp. 41 ff. ISBN 0262193949. The complete MIDI specification can be ordered from MIDI Manufacturers Association.

- ↑ Richard Boulanger (2000). “Introduction to sound design in Csound”, Richard Boulanger, ed: The Csound Book: Perspectives in Software Synthesis, Sound Design, Signal Processing,and Programming. MIT Press, pp. 5 ff. ISBN 0262522616.

- ↑ Robert Bruce Thompson, Barbara Fritchman Thompson (2003). “MIDI Audio”, PC Hardware in a Nutshell, 3rd ed. O'Reilly Media, Inc, p. 577. ISBN 059600513X.

- ↑ Eberhard Sengpiel. MIDI notes and their corresponding frequencies. Keyboard and frequencies. Retrieved on 2012-06-23.

- ↑ Philippe Blanchard, Dimitri Volchenkov (2011). “Equation (8.49) in §8.4.2 Encoding of a discrete model of music (MIDI) into a transition matrix”, Random Walks and Diffusions on Graphs and Databases: An Introduction. Springer, p. 156. ISBN 3642195911.

- ↑ Dan Hosken (2010). An Introduction to Music Technology. Taylor & Francis, p. 145. ISBN 0415878276.

- ↑ A. E. Cawkell, Tony Cawkell (1996). The Multimedia Handbook. Psychology Press, p. 151. ISBN 0415136660.

- ↑ Joseph Rothstein (1994). Midi: A Comprehensive Introduction, 2nd ed. A-R Editions, Inc., p. 184. ISBN 0895793091.

- ↑ Andrea Pejrolo, Rich DeRosa (2007). “Program change”, Acoustic and MIDI Orchestration for the Contemporary Composer. Elsevier, p. 6. ISBN 0240520211.

- ↑ For an outline of MIDI CC messages see Andrea Pejrolo, Rich DeRosa (2007). Acoustic and MIDI Orchestration for the Contemporary Composer. Elsevier. ISBN 0240520211.

KSF

KSF