Nuclear waste management

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

Worry about nuclear waste management is one of the barriers to reconsidering nuclear power. How much waste is produced compared to other sources of energy? How will it be contained, and what are the dangers to people and the environment? Like questions on safety, public perception of the dangers of nuclear waste is much worse than historical data shows.[2] The volume of waste per per terawatt-hour is 100,000 times less than coal.[3] Even if we look only at radioactivity released to the environment,[4] watt-for-watt nuclear power is 100 times less than coal.[5]

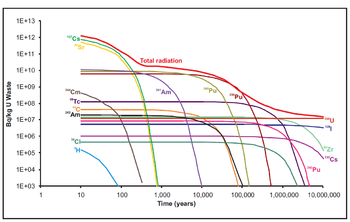

Much of the worry about nuclear waste centers around the long life of some low-level [6] isotopes in the waste (See Figure 1). There is concern about leakage into the environment decades or even centuries from now. Billion-dollar efforts to bury the waste deep under a mountain have only heightened public fears. Dry-cask storage at the power plants has proven to be a safe but temporary solution.[7] This interim storage has the advantage of being able to recover the "waste" and use it in newer reactors that can use the remaining 97% of available energy.

Transportation of wastes from reactors to storage or reprocessing sites must be done safely. Leakage into groundwater and ocean water near shore is a special concern. New reactor designs must address these concerns, even though they go beyond the design of the reactor itself. Will the waste be solid or liquid? Will it require special casks, or even special vehicles for transportation on public roads? (See Figure 2)

Fig.2 Transport of Nuclear Fuel in Japan.[8]

Other worries include the possibility of sabotage or theft of waste material that might be useful in a "dirty bomb". We should evaluate specific plans by considering likely scenarios. Is the storage facility away from any population center and not a target for an airplane crash, a truck bomb, or even a short-range missile? Is there a secure perimeter with intrusion detectors? If there is an intrusion, is cutting through the concrete and steel difficult enough that there will be plenty of time for a response from local law enforcement, or even a nearby military base? (See Figure 3)

Fig.3 Dry underground storage in the desert, safe but still recoverable.

In evaluating a new reactor design, we must look at the complete fuel cycle, not just the waste from the reactor itself. Are there any problems with the mining, processing, or transportation of the fuel, or with the reprocessing of spent fuel?

Interim Storage[edit]

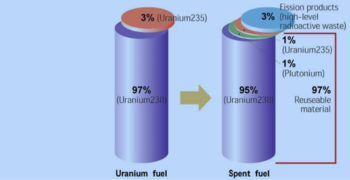

It is important that we make a distinction between spent fuel from nuclear power, and the waste from bomb production, which was often done in a rush with little concern for pollution. Spent fuel rods can be stored safely. Weapons waste poses a much bigger problem due to the large variety and sometimes unexpected characteristics of the waste material.[9] Spent fuel rods contain 97% of the energy in new rods (See Figure 4) and this energy can be used in advanced reactors. Weapons waste has nothing worth saving.

Reprocessing[edit]

Fig.6 A well-managed nuclear fuel cycle results in very little high-level waste. This waste may be melted into borosilicate glass and cast into stainless steel canisters for permanent disposal.[10]

- Processing of Used Nuclear Fuel World Nuclear Association

- Recycling used nuclear fuel - Orano la Hague video on the French recycling process

- 4000 employees, reprocessing Spent Nuclear Fuel for France and other countries

- Spent Nuclear Fuel (SNF): 95% U, 1% Pu, 4% fission products

- Vitrified waste volume 20% of original SNF volume, melted into stainless steel canisters. (See Figure 6)

The vitrification process is currently being used in France, Japan, Russia, UK, and USA. The capacity of western European vitrification plants is about 2,500 canisters (1000 tonnes) a year, and some have been operating for three decades.[11] So far, about 400,000 tonnes of used fuel has been discharged from commercial power reactors, of which about 30% has been reprocessed.[12]

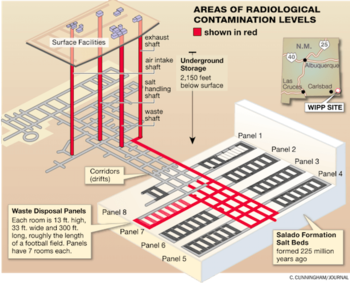

Permanent Disposal[edit]

After recovery of all the valuable isotopes in spent fuel, there will still be a small remainder of high-level waste. This waste can be permanently disposed in deep geological repositories, like WIPP,[13] already in use for bomb production waste. (See Figure 5) The canister in Figure 6 holds 175 liters of solid glass waste with ___ kg of highly-radioactive fission products. Waste from a typical 1000 MWe Pressurized Water Reactor will fill ___ of these canisters in a full year of operation. One 300-foot burial chamber at WIPP can hold ___ canisters.

Further Reading[edit]

- World Nuclear Association articles on the Nucldear Fuel Cycle including Fuel Recycling and Nuclear Waste Management.

Notes and References[edit]

- ↑ https://blogs.egu.eu/network/geosphere/2015/02/02/geopoll-what-should-we-do-with-radioactive-waste/

- ↑ “Over the last 40 years, thousands of shipments of commercially generated spent nuclear fuel have been made throughout the United States without causing any radiological releases to the environment or harm to the public.” - statement by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission quoted in Storage and Disposal of Radioactive Waste

- ↑ section 2.2 "A Beautifully Small Problem" in the book Why Nuclear Power has been a Flop.

- ↑ https://www.epa.gov/radtown/radioactive-wastes-coal-fired-power-plants

- ↑ https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/coal-ash-is-more-radioactive-than-nuclear-waste/ - The title is a bit misleading. From the article: "In fact, the fly ash emitted by a power plant—a by-product from burning coal for electricity—carries into the surrounding environment 100 times more radiation than a nuclear power plant producing the same amount of energy." "ounce for ounce, coal ash released from a power plant delivers more radiation than nuclear waste shielded via water or dry cask storage."

- ↑ Long-lived isotopes in spent nuclear fuel have both lower intensity and lower penetrating power than the short-lived fission products that are gone in 600 years. See the Nuclear Waste Lasts Forever section of our Debate Guide page.

- ↑ Connecticut Yankee, a 619 MWe reactor on the Connecticut River, ran for 28 years between 1968 and 1996. The spent fuel from those 28 years is stored in 43 casks on a concrete pad, 70 feet by 228 feet.

- ↑ https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/transport-of-nuclear-materials/transport-of-radioactive-materials.aspx

- ↑ A barrel containing plutonium mixed with kitty litter ruptured after it was stored at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, leading to "Nuclear accident in New Mexico ranks among the costliest in U.S. history" LA Times

- ↑ See Treatment and Conditioning of Nuclear Waste for more on these canisters and borosilicate glass, an insoluble, solid material that will remain stable for thousands of years.

- ↑ Treatment and Conditioning of Nuclear Waste, World Nuclear Association, Information Library, 2021.

- ↑ Processing of Used Nuclear Fuel World Nuclear Association, Information Library, 2020.

- ↑ The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) is a deep geological repository in a 250 million-year old salt formation. See the document Why Salt from the US Department of Energy.

KSF

KSF