Oxidation-reduction

From Citizendium - Reading time: 8 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 8 min

As modern chemistry began to emerge, with the work of the French chemist, Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794), chemists viewed oxidation as a class of chemical reactions in which a chemical species (e.g., a chemical element or compound) reacts with oxygen in the presence of heat to form an oxygen-containing product referred to as a 'calx', an 'oxide'.[1]

For example, the liquid (l) transition metal, mercury (Hg), an elementary substance, when heated to 300-350 oC, reacts with gaseous (g) oxygen (O2), also an elementary substance, to form the solid oxide, mercuric oxide (HgO), a binary ionic compound consisting of the mercuric cation and the oxide anion:

In the older terminology of early chemistry, the words 'combustion', 'burning', and 'calcination' were used to refer the transformation of one substance to another in the presence of atmospheric air (~21% oxygen) and a certain amount of heat, the product referred to as a 'calx'. The calcination of the metal, mercury, produced the calx, mercuric oxide. Initially, chemists did not know that the air, or that some component of the air, combined with the metal to produce the calx. They believed, incorrectly, that the process involved the metal releasing a substance, sometimes referred to as a 'principle', called phlogiston.

Modern chemical concept of oxidation and reduction[edit]

In modern chemistry, chemists recognize the oxidation reaction of a chemical species with oxygen as a special case of a more general phenomenon, namely a phenomenon in which electrons transfer from one substance to another, the oxidizing event consisting of the 'loss of electrons' from the first substance, the 'gain of electrons' by the second substance referred to as reduction. In the particular case of oxidation of a species through reaction with oxygen, oxygen gains the election and thereby becomes reduced.

For example, when the elemental metal, magnesium, Mg, a solid under ordinary conditions, reacts with molecular oxygen, O2, present in air, magnesium atoms exposed to oxygen each transfer two electrons, 2e-, to an oxygen atom, forming the ionic compound, magnesium oxide, MgO. Many such magnesium oxide compounds together form a crystalline structure. The balanced 'molecular' chemical reaction is written:

- 2Mg(s) + O2(g) → 2MgO(s), where s=solid, g=gas[2]

Breaking down that reaction to show its component oxidation and reduction reaction, chemists write:

- 2Mg(s) → 2Mg2+ + 4e– [oxidation of two magnesium atoms, a loss of four electrons]

- O2(g) + 4e– → 2O–2 [reduction of four oxygen atoms, a gain of four electrons]

Those are make-believe reactions to indicate the separate oxidation and reduction components of the overall reaction, make-believe because free electrons do not exist in solution. Rather, the electrons transfer directly from magnesium to oxygen. Adding the two component reactions eliminates the electrons and yields the balanced molecular reaction shown above.

A visible sample of elemental magnesium exposed to air acquires a sheen of magnesium oxide crystals that protects the underlying magnesium ions from the oxidation reaction.

Why does the electron transfer occur? A precise answer requires an understanding of quantum mechanics, which reveals that oxygen atoms have a much greater 'affinity' for electrons than do magnesium atoms. Metaphorically, and oversimplified, atoms in their neutral state behave 'as if' they wanted to fill to its natural capacity their so-called valence electron shell. An oxygen atom, a stronger electron attractor than a magnesium atom, requires two electrons to accomplish that goal.

Chemists recognize that such electron transfers can occur in more than one way:

(1) the complete transfer of one or more electrons from one species to another, exemplified paradigmatically by the transfer of electrons from a metal, such as sodium (Na), to a nonmetal, such as chlorine (Cl), to form an ionic compound, namely, sodium chloride (NaCl).

- 2Na → 2Na+ + 2e- [loss of electrons by Na = oxidation of Na]

- Cl2 + 2e- → 2Cl- [gain of electrons by Cl = reduction of Cl]

- 2Na + Cl2 → 2NaCl [formation of the ionic compound, NaCl]

(2) the partial transfer of electrons from one species to another, exemplified in the formation of an electron-sharing bond, a covalent bond, where the shared electrons spend more time near the second species than the first.

- 2H2 + O2 → 2H2O [or, 2HOH]

Each of the two H atoms in a molecule of H2O shares an electron with the O atom, but because the O atom has more protons in its nucleus than does the H atoms, the shared electrons spend more time nearer the O atom, with the result that the H atoms have effectively lost their pre-reaction full complement of electrons. The H atoms thus undergo oxidation and the O atom, reduction.

(3) the transfer of an electron covalently bonded to a proton, namely, a hydrogen atom, from one chemical species to another.

- H3C-CH3 → H2C=CH2 + H2

Here the hydrocarbon, ethane (H3C-CH3) loses two hydrogen atoms, hence two electrons, to form ethene, an alkene, the ethane undergoing oxidation, the ethene, reduction.

Redox: on the coupling of reduction and oxidation[edit]

It is important to emphasize that oxidation reactions and reduction reactions always occur as coupled reactions, which chemists call 'redox' reactions. When, as discussed earlier, elemental mercury, an electrically uncharged substance, reacts with elemental oxygen when heated, forming mercuric oxide, elemental mercury is oxidized, losing electrons gained by oxygen, oxygen then becoming reduced. The loss of electrons by elemental mercury transforms (oxidizes) it to the mercuric ion, Hg2+, an electrically charged substance, the superscript 2+ indicating it has lost two electrons, becoming doubly positively charged. The two electrons gained by each oxygen atom convert (reduce) the uncharged oxygen atom to an oxide, in this case, a doubly negatived charged ion, O2-.

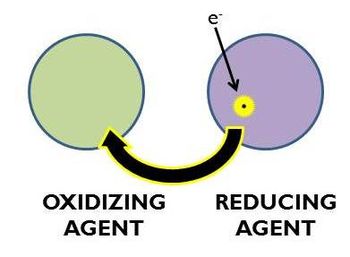

In a redox reaction that transfers one electron, the oxidizing agent receives/captures the electron and becomes reduced, the reducing agent donates/loses the electron and becomes oxidized.

In a redox reaction, the substance causing the oxidation—causing/capturing the electron(s) loss/lost—is referred to as the oxidizing agent; the substance causing the reduction—donating the electron(s) to the oxidizing agent is referred to as the reducing agent.

With the terminology of agents of oxidation and reduction, a redox reaction can also be described as:

An oxidizing agent is sometimes referred to as an oxidant, a reducing agent, a reductant. Thus, another way to describe a redox reaction:

Concept of electrochemical series[edit]

Not all oxidants have the same oxidizing strength....

Some biological implications[edit]

We humans live because oxidation reactions, more specifically, oxidation-reduction coupled reactions, can occur:

- We have learned that the oxidation of foodstuffs, organic compounds, like sugar and other carbohydrates, enables us, and the other systems that live in an oxygen-containing environment, to generate the energy needed to sustain the physiological work of living.

- The energy derives from the 'combustion', or oxidation, of the carbohydrate, whose electrons transfer under precise metabolic control, to oxygen, forming carbon dioxide and water, releasing the energy that held those electrons in their original bonds — a process referred to as 'respiration'.

- We have access to and can obtain the carbohydrates and oxygen because oxidation-reduction reactions, energized by sunlight, mediate the process of photosynthesis, which liberates oxygen from water through transfer of electrons to the carbon atoms of carbon dioxide, converting carbon dioxide by reduction to carbohydrate, allowing water's oxygen atoms, stripped of their hold on water's hydrogen atoms, to share their own electrons with each other, forming dioxygen molecules.

- The energy derives from the 'combustion', or oxidation, of the carbohydrate, whose electrons transfer under precise metabolic control, to oxygen, forming carbon dioxide and water, releasing the energy that held those electrons in their original bonds — a process referred to as 'respiration'.

Thus, photosynthesis and respiration recycle carbon dioxide and water, producing the energy that enables living systems to go on living.[3]

The key to biological energy transformations is the transfer of energy from one molecule to another. One of the two most common mechanisms for transferring energy in biochemical reactions involves the exchange of electrons between molecules. These types of reactions are known as oxidation-reduction (or redox) reactions.

- A loss of one or more electrons is known as oxidation and the molecule that loses electrons is said to be oxidized. In biochemical reactions, an oxidized molecule is often referred to as an electron acceptor, or, because it potentially can accept electrons from other species, as an oxidizing agent.

- Conversely, the gain of an electron is known as reduction and the molecule that gains the electron, the electron acceptor, or oxidizing agent is said to be reduced, and because it potentially can donate electrons to other species, it can be referred to as a reducing agent.

Note that an oxidation-reduction reaction does not necessarily require the participation of oxygen, only that electrons be exchanged. The process of reacting with oxygen is called oxidation solely because oxygen is one of the most common electron acceptors. Another point to note is that electrons can not exist in a free state, so the oxidation of one molecule must be accompanied by the reduction of another molecule.

History[edit]

The 'Father of Chemistry', Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1743-1794), in his Elements of Chemistry (originally published in French in 1789), writes of oxidation in relation to the products formed when metals (e.g., mercury, iron) are exposed to air and a certain amount of heat:

The term oxidation, or calcination, is chiefly used to signify the process by which metals exposed to a certain degree of heat are converted to oxides, by absorbing oxygen from the air.[1]

Lavoisier recognized calcination of metals as oxidation, the resulting oxides referred to as calxes, or calces, (sing., (calx).

Lavoisier's work revealed the common link — namely the requirement for the oxygen component of air, the chemical reaction of oxidation — among the air-requiring processes of:

- burning (combustion),

- rusting and other such so-called calcinations of metals, and

- breathing (respiration) by animals .[4]

Prior to Lavoisier, the chemist, Georg Ernst Stahl (1660-1734), taught that oxidation, as it came to be called later, involved the escape of a common constituent of combustible substances, including metals capable of calcination, referred to as phlogiston, whose concentration differed among combustible/calcinable substances. Coal, which burns violently, he considered nearly all phlogiston.

The phenomenon of converting a calx back to the metal it started as, by reacting the calx with burning coal, Stahl explained as returning the phlogiston back to the metal. That phenomenon was known as 'reduction', i.e., reducing a larger amount of calx to the smaller amount of the pure metal, the weight difference, however, contrary to Stahl's 'phlogiston theory', unless one assumed phlogiston had negative weight, as some did.

How Lavoisier came to replace the the phlogiston theory with the oxygenation theory is one of the great stories in the annals of the history of chemistry.[5]

As the concept of oxidation matured with the development of the atomic theory, the concept of reduction also became refined, and more importantly, became inextricably linked to oxidation as a simultaneous event that accompanied every oxidation event.

Some definitions[edit]

- At this point we introduce a few helpful definitions:

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (1799). Elements of Chemistry: In a new systematic order, containing all the modern discoveries, illustrated with thirteen copperplates, 4th Edition, translated by Robert Kerr. Google Books free full-text.

- ↑ In the older terminology of Lavoiser's day, magnesium oxide would have been referred to as the calx of magnesium.

- ↑ Hopkins WG. (2006) Photosynthesis and Respiration. New York: Chelsea House, imprint of Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780791085615. | Google Books preview, in particular chapter introducing bioenergetics.

- ↑ Lavoisier A. (1775) Memoir On The Nature Of The Principle Which Combines With Metals During Calcination And Increases Their Weight. (Read to the Academie des Sciences, Easter, 1775.) | Experiments On The Respiration Of Animals And On The Changes Which Happen To Air In Its Passage Through Their Lungs. (Read to the Academie des Sciences, 3rd May, 1777.) | Memoir On The Combustion Of Candles In Atmospereic Air And In Respirable Air. (Communicated to the Academie des Sciences, 1777.) | All Reproduced here.

- ↑ Jaffe B. (1976) Crucibles: the story of chemistry from ancient alchemy to nuclear fission. 4th ed. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486233420. Google Books preview. See chapters III and VI.

KSF

KSF