Potato

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 7 min

Freshly harvested potatoes. © Photo: Petréa Mitchell

The potato (pl. potatoes), also called Irish potato or white potato or, informally, spud, is one of the world's most important foods. It ranks as the fourth-most-important food crop, after corn (maize), wheat and rice. It provides more calories and more nutrients, more quickly, using less land and in a wider range of climates than any other plant.

It is the root of an herbaceous plant (Solanum tuberosum) that originally evolved in the northern Andean highlands.

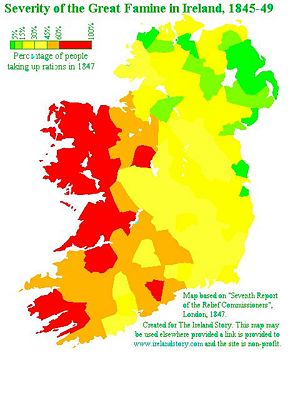

The potato was cultivated by various Andean civilizations for at least 2000 years before the Spanish were introduced to it by the Incas in the 16th century. During that time, many different varieties were developed by the Andean peoples, but it was mainly the common white potato that was brought to Europe for cultivation. The potato became a staple crop across northern Europe, but nowhere so much as in Ireland, where an epidemic of potato blight in 1845-46 produced a famine that killed a million or more people and forced as many to emigrate.

The United Nations has declared 2008 the International Year of the Potato.[1] It hopes that greater awareness of the merits of potatoes will contribute to the achievement of its Millennium Development Goals, by helping to alleviate poverty, improve food security and promote economic development.

The great diversity of potatoes developed in the Andes has been expanded even further around the world, so that there are varieties suited to nearly every climate, with harvest times anywhere from midsummer to late fall. Most prefer a well-drained, slightly acid soil, and are planted in the early spring.

Potatoes also come in a wide range of colors, with skin anywhere from brown to purple to red and white, yellow, red, or blue flesh. They are eaten fried, baked, mashed, boiled, or made into flour, and different varieties have been developed for each of these specific purposes.

Production and consumption[edit]

Many countries produce potatoes; almost all is for local consumption as the international market is small.

The ten leaders in production in 2007, in million metric tons were:

- 72 China

- 36 Russia

- 26 India

- 19 Ukraine

- 18 USA

- 12 Germany

- 11 Poland

- 8.5 Belarus

- 7.2 Netherlands

- 6.3 France

At first people were highly suspicious, but as economist Adam Smith concluded in 1776:

- "The very general use which is made of potatoes in [Britain] as food for man is a convincing proof that the prejudices of a nation, with regard to diet, however deeply rooted, are by no means unconquerable."

Served as "French fries", often alongside burgers and colas, potatoes are now an icon of globalization.

Belarusians lead the world with 345 kilos consumed per person per year.

History[edit]

Potatoes yield abundantly with little effort, and adapt readily to diverse climates so long as the climate is cool and moist enough for the plants to gather sufficient water from the soil to form the starchy tubers. Potatoes do not keep very well in storage and are vulnerable to molds that feed on the stored tubers, quickly turning them rotten. By contrast grain can be stored for several years without much risk of rotting.

Peru[edit]

Potatoes were first domesticated in Peru between 3000 BC and 2000 BC. In the altiplano, potatoes provided the principal energy source for the Inca Empire, its predecessors and its Spanish successor. In Peru above 10,000 feet altitude, tubers exposed to the cold night air turned into chuño; when kept in permanently-frozen underground storehouses, chuño can be stored for years with no loss of nutritional value. The Spanish fed chuño to the silver miners who produced vast wealth in the 16th century for the Spanish government.

Peru is home to up to 3,500 different varieties of edible tubers, according to the International Potato Center, whose headquarters are near Lima. The United Nations has designated 2008 as the "International Year of the Potato" and Peru hopes to use this to draw attention to itself and its crop. Alan García, the president, has ordered that a government-sponsored program of free breakfasts for poor families should serve bread made from a mixture of potato flour with wheat, which is more expensive and has to be imported. He also wants government food services to start serving chuño, a naturally freeze-dried potato that is traditionally eaten by Andean Indians. Boiled chuño and cheese are said to have replaced sandwiches at cabinet meetings. Peru grows 25 varieties commercially, but exports little. Peruvian yellow potatoes are prized by gourmets for mashing; tubular ollucos are firm and waxy.

Asia[edit]

The potato diffused widely after 1600, becoming a major food resource in Europe and East Asia. Following its introduction into China toward the end of the Ming dynasty, the potato immediately became a delicacy of the imperial family. After the middle period of the Qianlong reign (1735-96), population increases and a subsequent need to increase grain yields coupled with greater peasant geographic mobility, led to the rapid spread of potato cultivation throughout China, and it was acclimated to local natural conditions.

Boomgaard (2003) looks at the adoption of various root and tuber crops in Indonesia throughout the colonial period and examines the chronology and reasons for progressive adoption of foreign crops - sweet potato, Irish potato, bengkuang (yam beans), and cassava.

Europe[edit]

Sailors returning from Peru to Spain with silver presumably brought maize and potatoes for their own food on the trip. Historians speculate that leftover tubers (and maize) was carried ashore and planted. Basque fishermen from Spain used potatoes as ships stores for their voyages across Atlantic in the 15th century, and introduced the tuber to western Ireland, where they landed to dried their cod.

In 1580, English adventurer Francis Drake introduced potatoes into England along with his other Spanish booty when he returned from his famous circumnavigation of the globe. In 1588 botanist Carolus Clusius made a painting of what he called "Papas Peruanorum" from a specimen in Belgium; in 1601 he reported that potatoes were in common use in northern Italy for animal fodder and for human consumption.

The Spanish had an empire across Europe, and brought potatoes for their armies. Peasants along the way adopted the crop, which was less often pillaged by marauding armies than above-ground stores of grain. Across most of northern Europe, where open fields prevailed, potatoes were strictly confined to small garden plots because field agriculture was strictly governed by custom that prescribed seasonal rhythms for plowing, sowing, harvesting and grazing animals on fallow and stubble. This meant that potatoes were barred from large-scale cultivation because the rules allowed only grain to be planted in the open fields.[2] In France and Germany government officials and noble landowners promoted the rapid conversion of fallow land into potato fields after 1750.

In Ireland the expansion of potato cultivation was due entirely to the landless laborers, renting tiny plots from landowners who were interested only in raising cattle or in producing grain for market. A single acre of potatoes and the milk of a single cow was enough to feed a whole Irish family a monotonous but nutritionally adequate diet for a healthy, vigorous (and desperately poor) rural population. Often even poor families grew enough extra potatoes to feed a pig which could be sold for cash.

19th century[edit]

French physician Antoine Parmentier studied the potato intensely and in Examen chymique des pommes de terres (Paris, 1774) showed their enormous nutritional value. King Louis XVI and his court eagerly promoted the new crop, with Queen Marie Antoinette even wearing a headdress of potato flowers at a fancy dress ball. The annual potato crop of France soared to 21 million hectoliters in 1815 and 117 millions in 1840, allowing a concomitant growth in population while avoiding the Malthusian trap. Although potatoes had become widely familiar in Russia by 1800, they were confined to garden plots until the grain failure in 1838-1839 persuaded peasants and landlords in central and northern Russia to devote their fallow fields to raising potatoes. Potatoes yielded from two to four times more calories per acre than grain did, and eventually came to dominate the food supply in eastern Europe. Boiled or baked potatoes were cheaper than rye bread, just as nutritious, and did not require a gristmill for grinding. On the other hand cash-oriented landlords realized that grain was much easier to ship, store and sell, so both grain and potatoes coexisted.[3]

Throughout Europe the most important new food in the 19th century was the potato, which had three major advantages over other foods: its lower rate of spoilage, its bulk (which easily satisfied hunger), and its cheapness. The crop slowly spread across Europe, such that, for example, by 1845 it occupied one-third of Irish arable land. Potatoes comprised about 10% of the caloric intake of Europeans. Other foods imported from the New World included cod, sugar, rice, flour, and rum. These also provided an additional 10% of daily calories and proved a crucial factor in biodiversity of crops, thus preventing famines.[4]

In Britain the potato promoted economic development by underpinning the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. As a cheap source of calories and nutrients that was easy for urban workers to cultivate on small backyard plots. Potatoes became popular in the north of England, where coal was readily available, so a potato-driven population boom provided ample workers for the new factories. Marxist Friedrich Engels even declared that the potato was the equal of iron for its "historically revolutionary role.

The Lumper potato, widely cultivated in western and southern Ireland before and during the great famine, was tasteless, wet, and poorly resistant to the potato blight, but yielded large crops and usually provided adequate calories for peasants and laborers. Heavy dependence on this potato led to disaster when the potato blight turned a newly harvested potato into a putrid mush in minutes. The Irish Famine in the British-controlled island of Ireland, 1845-49, was a catastrophic failure in the food supply that led to approximately a million deaths from famine and disease, vast social disruption and to massive emigration.

The Dutch potato-starch industry grew rapidly in the 19th century, especially under the leadership of entrepreneur Willem Albert Scholten (1819-92).

US and Canada[edit]

Potatoes were planted in Idaho as early as 1838; by 1900 the state's production exceeded a million bushels. Prior to 1910, the crops were stored in barns or root cellars, but by the 1920s potato cellars came into use. U.S. potato production has increased steadily; two-thirds of the crop comes from Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Colorado, and Maine, and potato growers have strengthened their position in both domestic and foreign markets.

By the 1960s, the Canadian Potato Research Centre in Fredericton, New Brunswick, was one of the top six potato research institutes in the world. Established in 1912 as a dominion experimental station, the station began in the 1930s to concentrate on breeding new varieties of disease-resistant potatoes. In the 1950s-60s the growth of the french fry industry in New Brunswick led to a focus on developing varieties for the industry. By the 1970s the station's potato research was broader than ever before, but the station and its research programs had changed, as emphasis was placed on serving industry rather than potato farmers in general. Scientists at the station even began describing their work using engineering language rather than scientific prose.[5]

notes[edit]

- ↑ See International Year of the Potato website

- ↑ William H. McNeill, "How the Potato Changed the World's History." Social Research 1999 66(1): 67-83.

- ↑ William L. Langer, "American Foods and Europe's Population Growth 1750-1850," Journal of Social History, 8#2 (1975), pp. 51-66

- ↑ John Komlos, "The New World's Contribution to Food Consumption During the Industrial Revolution." Journal of European Economic History 1998 27(1): 67-82. Issn: 0391-5115

- ↑ Steven Turner, and Heather Molyneaux, "Agricultural Science, Potato Breeding and the Fredericton Experimental Station, 1912-66." Acadiensis 2004 33(2): 44-67. Issn: 0044-5851

KSF

KSF