Republican Party (United States), history

From Citizendium - Reading time: 24 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 24 min

The Republican Party began in 1854 with the formation of the Third Party System. Since around 1880, it has come to be known as the GOP (or "Grand Old Party"). It was the dominant national political party until 1932. After which time it struggled while the Democratic Party under the New Deal Coalition was dominant. Since 1968, the GOP has won 7 of 10 presidential elections (losing in 1976, 1992, and 1996), but infrequently controlling Congress. Its great rival is the Democratic Party.

Formation and Early Growth: 1854-1860[edit]

The Republican party began as a spontaneous grass roots protest against the Kansas Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed slavery into western territories where it had been forbidden by earlier compromises. The creation of the new party, along with the death of the Whig Party, realigned American politics. The central issues were new, as were the voter alignments, and the balance of power in Congress. The central issues became slavery, race, civil war and the reconstruction of the Union into a more powerful nation, with rules changed that gave the vote to former slaves.

Issues: Slavery[edit]

Republican activists denounced the Kansas-Nebraska act as proof of the power of the Slave Power--the powerful class of slaveholders who were conspiring to control the federal government and to spread slavery nationwide. The name "Republican" gained such favor in 1854 because "republicanism" was the paramount political value the new party meant to uphold. The name also echoed the former Jeffersonian party of the First Party System. The party founders adopted the name "Republican" to indicate it was the carrier of "republican" beliefs about civic virtue, and opposition to aristocracy and corruption. [1]

Two small cities of the Yankee diaspora, Ripon, Wisconsin, and Jackson, Michigan, claim the birthplace honors. [2] Ripon held the first county convention on March 20, 1854. Jackson held the first statewide convention where delegates on July 6, 1854 declared their new party opposed to the expansion of slavery into new territories and selected a state-wide slate of candidates. The Midwest took the lead in forming state party tickets, while the eastern states lagged a year or so. There were no efforts to organize the party in the South, apart from a few areas adjacent to free states. The new party was sectional, based in the northeast and northern Midwest--areas with a strong Yankee presence. It had only scattered support in slave states before the Civil War.[3]

The first presidential nomination in 1856 when to an obscure western explorer John C. Fremont, as the party crusaded against the Slave Power with the slogan, "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free men, Fremont and victory!" Democrats warned darkly that disunion and Civil War would result. The remnants of the Know Nothing movement prevented the new party from sweeping the North, and the Democrats elected James Buchanan. By 1858 the Know Nothings were gone and the Republicans swept the North. The 1860 election seemed a certain victory, for the party had majorities in states with a majority of the electoral votes. In the event the opposition split three ways, and Abraham Lincoln coasted to an easy victory, carrying 18 states with 190 electoral votes, while the opposition carried 15 states (mostly in the South) with 123 electoral votes. Lincoln had 1.9 million popular votes.

Modernization[edit]

Besides opposition to slavery, the new party put forward a modernizing vision --emphasizing higher education, banking, railroads, industry and cities, while promising free homesteads to farmers. It vigorously argued that free-market labor was superior to slavery and the very foundation of civic virtue and true American values - this is the "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men" ideology explored by historian Eric Foner [4]. The Republicans absorbed the previous traditions of its members, most of whom had been Whigs, and some of whom had been Democrats or members of third parties (especially the Free Soil Party and Know-Nothings (American Party). Many Democrats who joined up were rewarded with governorships. [5] or seats in the U.S. Senate.[6] Since its inception, its chief opposition has been the Democratic Party, but the amount of flow back and forth of prominent politicians between the two parties was quite high from 1854 to 1896.

Ethnocultural voting[edit]

Historians have explored the ethnocultural foundations of the party, along the line that ethnic and religious groups set the moral standards for their members, who then carried those standards into politics. The churches also provided social networks that politicians used to sign up voters. The pietistic churches, heavily influenced by the revivals of the Second Great Awakening, emphasized the duty of the Christian to purge sin from society. Sin took many forms--alcoholism, polygamy and slavery became special targets for the Republicans. The Yankees, who dominated New England, much of upstate New York, and much of the upper Midwest were the strongest supporters of the new party. This was especially true for the pietistic Congregationalists and Presbyterians among them and (during the war), the Methodists, along with Scandinavian Lutherans. The Quakers were a small tight-knit group that was heavily Republican. The liturgical churches (Roman Catholic, Episcopal, German Lutheran), by contrast, largely rejected the moralism of the GOP; most of their adherents voted Democratic. [7]

Politics 1854-1860[edit]

John C. Frémont ran as the first Republican nominee for President in 1856, using the political slogan: "Free soil, free labor, free speech, free men, Frémont." Although Frémont's bid was unsuccessful, the party showed a strong base. It dominated in New England, New York and the northern Midwest, and had a strong presence in the rest of the North. It had almost no support in the South, where it was roundly denounced in 1856-60 as a divisive force that threatened civil war. The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 ended the domination of the fragile coalition of pro-slavery southern Democrats and conciliatory northern Democrats which had existed since the days of Andrew Jackson. Instead, a new era of Republican dominance based in the industrial and agricultural north ensued. Republicans still often refer to their party as the "party of Lincoln" in honor of the first Republican President.

- See also: American election campaigns in the 19th century

- See also: Third Party System

Civil War and Reconstruction: 1861-1876[edit]

Civil War: 1861-1865[edit]

Lincoln proved brilliantly successful in uniting the factions of his party to fight for the Union.[8] However he usually fought the Radical Republicans who demanded harsher measures. Most Democrats at first were War Democrats, and supportive until the fall of 1862. When Lincoln added the abolition of slavery as a war goal, many war Democrats became "peace Democrats." All the state Republican parties accepted the antislavery goal except Kentucky. In Congress, the party passed major legislation to promote rapid modernization, including a national banking system, high tariffs, an income tax, many excise taxes, paper money issued without backing ("greenbacks"), a huge national debt, homestead laws, and aid to education and agriculture. The Republicans denounced the peace-oriented Democrats as Copperheads and won enough War Democrats to maintain their majority in 1862; in 1864, they formed a coalition with many War Democrats as the "National Union Party" which reelected Lincoln easily, then folded back into the Republican party. During the war, upper middle-class men in major cities formed Union Leagues, to promote and help finance the war effort.

Reconstruction: Blacks, Carpetbaggers and Scalawags[edit]

In Reconstruction, how to deal with the ex-Confederates and the freed slaves, or Freedmen, were the major issues. By 1864, Radical Republicans controlled Congress and demanded more aggressive action against slavery, and more vengeance toward the Confederates. Lincoln held them off, but just barely. Republicans at first welcomed President Andrew Johnson; the Radicals thought he was one of them and would take a hard line in punishing the South. Johnson however broke with them and formed a loose alliance with moderate Republicans and Democrats. The showdown came in the Congressional elections of 1866, in which the Radicals won a sweeping victory and took full control of Reconstruction, passing key laws over the veto. Johnson was impeached by the House, but acquitted by the Senate. With the election of Ulysses S. Grant in 1868, the Radicals had control of Congress, the party and the Army, and attempted to build a solid Republican base in the South using the votes of Freedmen, Scalawags and Carpetbaggers, supported directly by U.S. Army detachments. Republicans all across the South formed local clubs called Union Leagues that effectively mobilized the voters, discussed issues, and when necessary fought off Ku Klux Klan attacks. Thousands died on both sides.

Grant supported radical reconstruction programs in the South, the 14th Amendment, and equal civil and voting rights for the freedmen. Most of all he was the hero of the war veterans, who marched to his tune. The party had become so large that factionalism was inevitable; it was hastened by Grant's tolerance of high levels of corruption typified by the Whiskey Ring. The "Liberal Republicans" split off in 1872 on the grounds that it was time to declare the war finished and bring the troops home. Many of the founders of the GOP joined the movement, as did many powerful newspaper editors. They nominated Horace Greeley, who gained unofficial Democratic support, but was defeated in a landslide. The depression of 1873 energized the Democrats. They won control of the House and formed "Redeemer" coalitions which recaptured control of each southern state, in some cases using threats and violence.

Reconstruction came to an end when the contested election of 1876 was awarded by a special electoral commission to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes who promised, through the unofficial Compromise of 1877, to withdraw federal troops from control of the last three southern states. The region then became the Solid South, giving overwhelming majorities of its electoral votes and Congressional seats to the Democrats until 1964.

In terms of racial issues, "White Republicans as well as Democrats solicited black votes but reluctantly rewarded blacks with nominations for office only when necessary, even then reserving the more choice positions for whites. The results were predictable: these half-a-loaf gestures satisfied neither black nor white Republicans. The fatal weakness of the Republican party in Alabama, as elsewhere in the South, was its inability to create a biracial political party. And while in power even briefly, they failed to protect their members from Democratic terror. Alabama Republicans were forever on the defensive, verbally and physically." [Woolfolk p 134]

Social pressure eventually forced most Scalawags to join the conservative/Democratic Redeemer coalition. A minority persisted and formed the "tan" half of the "Black and Tan" Republican party, a minority in every southern state after 1877. (DeSantis 1998)

Gilded Age: 1877-1894[edit]

The "GOP" (as it was now nicknamed) split into factions in the late 1870s. The Stalwarts, followers of Senator Conkling, defended the spoils system. The Half-Breeds, who followed Senator James G. Blaine of Maine, pushed for Civil service reform. Independents who opposed the spoils system altogether were called "Mugwumps". In 1884 they rejected James G. Blaine as corrupt and helped elect Democrat Grover Cleveland; most returned to the party by 1888.

As the Northern post-bellum economy boomed with heavy and light industry, railroads, mines, and fast-growing cities, as well as prosperous agriculture, the Republicans took credit and promoted policies to keep the fast growth going. They supported big business generally, hard money (i.e. the gold standard), high tariffs, and high pensions for Union veterans. By 1890, however, the Republicans had agreed to the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Interstate Commerce Commission in response to complaints from owners of small businesses and farmers. The high McKinley Tariff of 1890 hurt the party and the Democrats swept to a landslide in the off-year elections, even defeating McKinley himself.

Ethnocultural Voters: pietistic Republicans versus liturgical Democrats[edit]

From 1860 to 1912, the Republicans took advantage of the association of the Democrats with "Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion." Rum stood for the liquor interests and the tavernkeepers, in contrast to the GOP, which had a strong dry element. "Romanism" meant Catholics, especially Irish Americans, who ran the Democratic party in every big city, and whom the Republicans denounced for political corruption. "Rebellion" stood for the Confederates who tried to break the Union in 1861, and the Copperheads in the North who sympathized with them.

Demographic trends aided the Democrats, as the German and Irish Catholic immigrants were Democrats, and outnumbered the English and Scandinavian Republicans. During the 1880s and 1890s, the Republicans struggled against the Democrats' efforts, winning several close elections and losing two to Grover Cleveland (in 1884 and 1892). Religious lines were sharply drawn [Kleppner 1979]. Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Scandinavian Lutherans and other pietists in the North were tightly linked to the GOP. In sharp contrast, liturgical groups, especially the Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans, looked to the Democratic party for protection from pietistic moralism, especially prohibition. Both parties cut across the class structure, with the Democrats more bottom-heavy.

Cultural issues, especially prohibition and foreign language schools became important because of the sharp religious divisions in the electorate. In the North, about 50% of the voters were pietistic Protestants (Methodists, Scandinavian Lutherans, Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Disciples of Christ) who believed the government should be used to reduce social sins, such as drinking. Liturgical churches (Roman Catholics, German Lutherans, Episcopalians) comprised over a quarter of the vote and wanted the government to stay out of the morality business. Prohibition debates and referenda heated up politics in most states over a period of decade, as national prohibition was finally passed in 1918 (and repealed in 1932), serving as a major issue between the wet Democracy and the dry GOP. (Kleppner 1979)

| Voting Behavior by Religion, Northern USA Late 19th century | ||

| % Dem | % GOP | |

| Immigrant Groups | ||

| Irish Catholics | 80 | 20 |

| All Catholics | 70 | 30 |

| Confessional German Lutherans | 65 | 35 |

| German Reformed | 60 | 40 |

| French Canadian Catholics | 50 | 50 |

| Less Confessional German Lutherans | 45 | 55 |

| English Canadians | 40 | 60 |

| British Stock | 35 | 65 |

| German Sectarians | 30 | 70 |

| Norwegian Lutherans | 20 | 80 |

| Swedish Lutherans | 15 | 85 |

| Haugean Norwegians | 5 | 95 |

| Natives: Northern Stock | ||

| Quakers | 5 | 95 |

| Free Will Baptists | 20 | 80 |

| Congregational | 25 | 75 |

| Methodists | 25 | 75 |

| Regular Baptists | 35 | 65 |

| Blacks | 40 | 60 |

| Presbyterians | 40 | 60 |

| Episcopalians | 45 | 55 |

| Natives: Southern Stock (living in North) | ||

| Disciples | 50 | 50 |

| Presbyterians | 70 | 30 |

| Baptists | 75 | 25 |

| Methodists | 90 | 10 |

Source: Paul Kleppner, The Third Electoral System 1853-1892 (1979) p. 182

From Realignment to Reform: 1896-1920: The Progressive Era[edit]

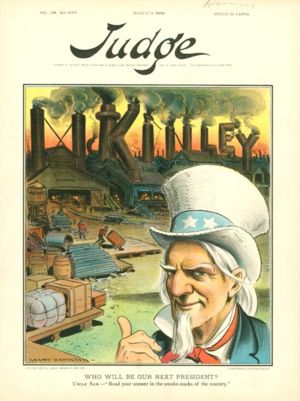

The election of William McKinley in 1896 was a realigning election that changed the balance of power, and introduced new rules, new issues and new leaders. It did not, however, see the emergence of a new major party. The Republican sweep of the 1894 Congressional elections presaged the McKinley landslide of 1896, which was repeated in 1900, thus locking the GOP in full control of the national government and most northern state governments. The GOP made major gains as well in the border states. The Fourth Party System was dominated by Republican presidents, with the exception of the two terms of Democrat Woodrow Wilson, 1912-1920.

McKinley and Realignment[edit]

McKinley promised that high tariffs would end the severe hardship caused by the Panic of 1893, and that the GOP would guarantee a sort of pluralism in which all groups would benefit. He denounced William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee, as a dangerous radical whose plans for "Free Silver" at 16-1 (or Bimetallism) would bankrupt the economy.

McKinley relied heavily on industry and the middle classes for his support and cemented the Republicans as the party of business; his campaign manager, Ohio's Mark Hanna, developed a detailed plan for getting contributions from the business world, and McKinley outspent his rival William Jennings Bryan by a large margin. McKinley was the first president to promote pluralism, arguing that prosperity would be shared by all ethnic and religious groups.

Roosevelt and Progressivism[edit]

Theodore Roosevelt, who became president in 1901, had the most dynamic personality in the nation. Roosevelt had to contend with men like Senator Mark Hanna, whom he outmaneuvered to gain control of the convention in 1904 that renominated him. More difficult to handle was conservative House Speaker Joseph Gurney Cannon.

Roosevelt achieved modest legislative gains in terms of railroad legislation and pure food laws. He was more successful in Court, bringing antitrust suits that broke up the Northern Securities trust and Standard Oil. Roosevelt moved left in his last two years in office but was unable to pass major Square Deal proposals.

Roosevelt did succeed in naming his successor Secretary of War William Howard Taft who easily defeated Bryan again in 1908.

Progressive insurgents vs. Conservatives[edit]

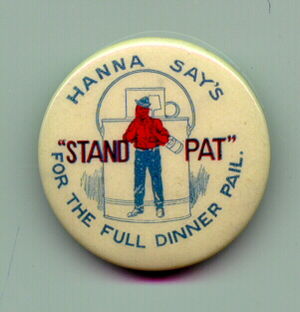

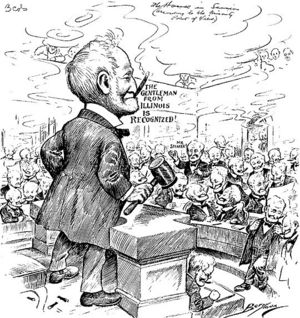

The GOP was divided between insurgents and stand-patters (liberals and conservatives, to use 21st century terms). Theodore Roosevelt was an enormously popular president (1901-1909), and he transferred the office to William Howard Taft. Taft, however, did not have TR's enormous popularity nor his ability to bring rival factions together. When Taft sided with the standpatters under Speaker Joe Cannon and Senate leader Nelson Aldrich, the insurgents revolted. Led by George Norris the insurgents took control of the House away from Cannon and imposed a new system whereby committee chairmanships depended on seniority (years of membership on the committee), rather than party loyalty.

The tariff issue was pulling the GOP apart. Roosevelt tried to postpone the issue but Taft had to meet it head on in 1909 with the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act. Eastern conservatives led by Nelson A. Aldrich wanted high tariffs on manufactured goods (especially woolens), while Midwesterners called for low tariffs. Aldrich tricked them by lowering the tariff on farm products, which outraged the farmers. In a stunning comeback the Democrats won control of the House in 1910, as the GOP rift between insurgents and conservatives widened.

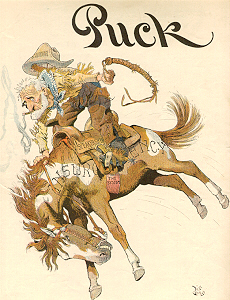

Roosevelt sided with the insurgents and, after long indecision, decided to run against Taft for the 1912 nomination. Roosevelt had to steamroll over insurgent Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin, turning an ally into an enemy. Taft outmaneuvered Roosevelt and controlled the convention. Roosevelt walked out and formed a third party, the "Progressive" or "Bull Moose" party. Very few officeholders supported him, and the new party collapsed by 1914. With the GOP vote divided in half, Democrat Woodrow Wilson easily won the 1912 election, and was narrowly reelected in 1916.

State and Local Politics[edit]

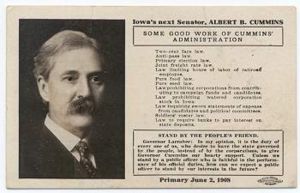

The Republicans welcomed the Progressive Era at the state and local level. The first important reform mayor was Hazen S. Pingree of Detroit (1890-97) who was elected governor of Michigan in 1896. In New York City the Republicans joined nonpartisan reformers to battle Tammany Hall, and elected Seth Low (1902-03). Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones was first elected mayor of Toledo as a Republican in 1897, but was reelected as an independent when his party refused to renominate him. In Iowa Senator Albert Cummins came up with the "Iowa Idea" that blamed the trust or monopoly problem on the high tariff, angering the eastern industrialists and factory workers. Many Republican civic leaders, following the example of Mark Hanna, were active in the National Civic Federation, which promoted urban reforms and sought to avoid wasteful strikes.

Conservative Ascendency: 1920-1932[edit]

Harding-Coolidge-Hoover, 1920-1932[edit]

The party controlled the presidency throughout the 1920s, running on a platform of opposition to the League of Nations, high tariffs, and promotion of business interests. Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover were resoundingly elected in the elections of 1920, 1924 and 1928 as the Democrats were deeply split on prohibition and religion. The breakaway efforts of Senator Robert LaFollette in 1924 failed to stop a landslide for Coolidge, and his movement fell apart. The Teapot Dome Scandal threatened to hurt the party but Harding died and Coolidge blamed everything on him, as the opposition splintered in 1924. The pro-business policies of the decade seemed to produce an unprecedented prosperity--until the Wall Street Crash of 1929 heralded the Great Depression. Although the party did very well in large cities and among ethnic Catholics in presidential elections of 1920-24, it was unable to hold those gains in 1928. By 1932 the cities--for the first time ever--had become Democratic strongholds.

The African American vote held for Hoover in 1932, but started moving toward Roosevelt. By 1940 the majority of northern blacks were voting Democratic. Southern blacks who could vote (in border states) were split; disenfranchised blacks in the South probably preferred the Republicans.

The Great Depression cost Hoover the presidency with the 1932 landslide election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition controlled American politics for most of the next three decades, excepting the two-term presidency of Republican Dwight Eisenhower.

The Great Depression and World War II[edit]

Minority parties tend to factionalize and after 1936 the GOP split into a conservative faction (dominant in the West and Southeast) and a liberal faction (dominant in the Northeast) – combined with a residual base of inherited progressive Republicanism active throughout the century. In 1936 Kansas governor Alf Landon and his young followers defeated the Herbert Hoover faction. Landon generally supported most New Deal programs, but carried only two states in the Roosevelt landslide.

Senator Robert Taft of Ohio represented the Midwestern wing of the party that continued to oppose New Deal reforms and continued to champion isolationism. Thomas Dewey, governor of New York, represented the Northeastern wing of the party. Dewey did not reject the New Deal programs, but demanded more efficiency, more support for economic growth, and less corruption. He was more willing than Taft to support Britain in 1939-40. After the war the isolationists wing strenuously opposed the United Nations, and was half-hearted in opposition to world Communism. Senator William F. Knowland's (R-CA) sobriquet was the Senator from Formosa (Taiwan).

Eisenhower & Nixon[edit]

Dwight Eisenhower, an internationalist allied with the Dewey wing, challenged Taft in 1952 on foreign policy issues. The two men were not far apart on domestic issues. Eisenhower's victory broke a 20 year Democratic lock on the White House. Eisenhower did not try to roll back the New Deal, but he did expand the Social Security system and built the Interstate Highway system.

The conservatives in 1964 made a comeback under the leadership of Barry Goldwater who defeated Nelson Rockefeller as the Republican candidate in the 1964 presidential convention. Goldwater was strongly opposed to the New Deal and the United Nations, but he rejected isolationism and containment, calling for an aggressive anti-Communist foreign policy.

In 1968, using growing voter disgust at Johnson's Great Society programs, Civil Rights, urban violence, and U.S. Supreme Court decisions that ended school prayer, liberalized pornography laws, and restricted police action, and the Vietnam War Richard Nixon played to a vast section of American middle-class voters he called the Silent Majority. He won the 1968 Presidential election, but it was another close race.

Any long-term voter movement toward the GOP was interrupted by the Watergate Scandal, which forced Nixon to resign in 1974 under threat of impeachment. Gerald Ford succeeded Nixon and gave him a full pardon--much to the disappointment of most Americans and thereby giving the Democrats a powerful issue they used to sweep the 1974 off-year elections. Ford never fully recovered from the political fallout of this pardon (even within his own party), and in 1976 he barely defeated Ronald Reagan for the nomination. The taint of Watergate and the nation's economic difficulties contributed to the election of Democrat Jimmy Carter in 1976, running as a Washington outsider.

Strength of Parties 1977[edit]

How the Two Parties Stood after the 1976 Election:

| Party | Republican | Democratic | Independent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Party ID (Gallup) | 22% | 47% | 31% |

| Congressmen | 181 | 354 | |

| House | 143 | 292 | |

| Senate | 38 | 62 | |

| % House popular vote nationally | 42% | 56% | 2% |

| in the East | 41% | 57% | 2% |

| in the South | 37% | 62% | 2% |

| in the Midwest | 47% | 52% | 1% |

| in the West | 43% | 55% | 2% |

| Governors | 12 | 37 | 1 |

| State Legislators | 2,370 | 5,128 | 55 |

| 31% | 68% | 1% | |

| State legislature control | 18 | 80 | 1 * |

| in the East | 5 | 13 | 0 |

| in the South | 0 | 32 | 0 |

| in the Midwest | 5 | 17 | 1 * |

| in the West | 8 | 18 | 0 |

| States' one party control of legislature and governorship |

1 | 29 | 0 |

*The unicameral Nebraska legislature, in fact controlled by the Republicans, is technically nonpartisan.

Source: Everett Carll Ladd Jr. Where Have All the Voters Gone? The Fracturing of America's Political Parties (1978) p.6

Long-term Changes in Party Demographics since 1940[edit]

Moderate Republicans of 1940-80[edit]

The term Rockefeller Republican was used 1960-80 to designate a faction of the party holding "moderate" views similar to those of the late Nelson Rockefeller, governor of New York from 1959 to 1974 and vice president under President Gerald Ford in 1974-77. Before Rockefeller, Tom Dewey, governor of New York 1942-54 and GOP presidential nominee in 1944 and 1948 was the leader. Dwight Eisenhower reflected many of their views. An important leader in the 1950s was Connecticut Republican Senator Prescott Bush, father and grandfather of presidents of George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush. After Rockefeller left the national stage in 1976, this faction of the party was more often called "moderate Republicans," in contrast to the conservatives who rallied to Ronald Reagan. Historically, Rockefeller Republicans were moderate or liberal on domestic and social policies. They favored New Deal programs, including regulation and welfare. They were very strong supporters of civil rights. They were strongly supported by big business on Wall Street (New York City). In fiscal policy they favored balanced budgets and relatively high tax levels to keep the budget balanced. They sought long-term economic growth through entrepreneurships, not tax cuts. In state politics, they were strong supporters of state colleges and universities, low tuition, and large research budgets. They favored infrastructure improvements, such as highway projects. In foreign policy they were internationalists, and anti-Communists. They felt the best way to counter Communism was sponsoring economic growth (through foreign aid), maintaining a strong military, and keeping close ties to NATO. Geographically their base was the Northeast, from Pennsylvania to Maine.

Suburbia[edit]

The suburban electorate passed the city electiorate in the 1950s, as Eisenhower showed unusually strength there. The history of suburban politics is encapsulated in Nassau County (New York), just east of New York City, where a moderate Republican party machine operated. Despite predictions that the New Deal spelled the demise of the political machine, Nassau provided fertile ground for a party organization that rivaled its big city Democratic counterparts. The traditionally GOP county underwent a booming expansion during 1945-60, with an influx of new residents, many with previous Democratic party affiliations. In established villages and new housing developments such as Levittown, under the canny leadership of J. Russel Sprague, the party used patronage and community organizing techniques to build its base among ethnic voters, young people, and new homeowners. The party expanded beyond its white Protestant base, with Italian Americans becoming particularly prominent in party leadership. Sprague was both party leader and county executive. That post was created in 1936 under a new charter engineered by Sprague to update a municipal apparatus unable to meet the infrastructure and development needs of a county that by 1960 had 1.3 million residents. Democrats and reformers had promoted charter revision for decades, and some consolidation of government services did take place. As county "boss," Sprague ruled with an iron hand. Nassau's pluralities for such candidates as Governor Thomas E. Dewey and President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Sprague's fundraising prowess made him a force in national party politics. He advocated a moderate, middle-of-the-road position that recognized expectations created by the New Deal while criticizing what were claimed to be Democratic excesses. After leaving elective office and party leadership, Sprague became a major campaign issue when the Democrats, in a 1961 historic upset, won the county executive post by both lambasting Sprague, tainted by a racetrack-stock scandal, and criticizing the developer-friendly "Spragueland" regime that had governed Nassau for decades. Soon after Sprague died in 1969, the Nassau GOP regained its control of the county government and reestablished virtual one-party rule until the 1990s.[9]

An even longer reign of power characterized GOP machine control of Delaware County, Pennsylvania, a rural and suburban area south of Philadelphia. William McClure controlled the GOP from 1875 until his death in 1907; his son John J. McClure, was in control from 1907 until his death in 1965. McLarnon (1998) has four main findings. First, political machines were not confined to big cities; the demographic and political peculiarities of suburban counties lent themselves to continued domination by political machines long after the heyday of the city machine had passed. Secondly, neither the New Deal, immigration restriction, nor the rise of organized labor destroyed all the old Republican machines. Delaware was one of several similar counties in southeastern Pennsylvania where the GOP continued to hold sway throughout the 20th century. Thirdly, not all blacks switched their electoral loyalties to the Democratic party in 1936. The black population of Chester, Delaware County's industrial city, generally voted Republican for offices below the presidential level. Finally, the citizens of Delaware County supported and continues to support the Republican machine because the machine delivered and continues to deliver those things that the citizens want most. At the beginning of the century, the machine provided food, work, and police protection to Chester's European and black immigrants. During Prohibition, it supplied the county with liquor. Through the Depression, patronage and close alliances with local industrialists kept a significant portion of machine loyalists employed. In the 1950s and 1960s the machine kept taxes low, initiated a war on organized vice, successfully defeated all threats to home rule, and discouraged blacks from settling in historically white communities. The trash was collected, the snow plowed, the streets repaired. The buses ran on time, the playgrounds and parks were clean, and the schools acceptably average. These were the most important concerns of a majority of county's citizens. While the citizens and their concerns changed over time, two things seem to have remained constant: the McClures', and their successors' ability to read and react to the needs of the electorate; and the fact that rarely, if ever, has a desire for honest, democratic government been high on Delaware County voters' list of priorities.[10]

Rise of the right[edit]

Barry Goldwater crusaded against the Rockefeller Republicans, beating Rockefeller narrowly in the California primary of 1964. That set the stage for a conservative resurgence, based in the South and West, in opposition to the Northeast. Brennan (1995) stresses that conservatives in the late 1950s and early 1960s had many internal problems to overcome before they could mount an effective challenge to the hegemony of the distrusted Eastern Establishment, typified by Nelson A. Rockefeller. The conservative movement had some newspapers and magazines (especially William F. Buckley, Jr.'s National Review) and one charismatic national leader, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater. The movement gained momentum once they had established a unity out of diverse elements on the Right with a common commitment to a militant anticommunism, and once they had succeeded in mobilizing a grassroots base inside a number of state and local organizations in the Sun Belt on behalf of a draft Goldwater campaign in 1960. Although Nixon was acceptable to the conservatives, they worried that he compromised with Rockefeller in 1960. His defeat in 1960 removed a major obstacle and also gave ammunition to those who wanted "a choice, not an echo" (to echo a Goldwater slogan). After 1960 liberals and moderates in the Republican party failed to appreciate the magnitude of the challenge they faced on the grass-roots level. They too readily equated their conservative opponents in the party with the "lunatic fringe" and did not take them seriously until they found themselves deposed by a grass roots insurgency of the sort unknown in the party since 1912.[11] Goldwater's landslide defeat opened the way to a liberal Democratic resurgence, but did little to help the liberal wing of the GOP. The failues of the Great Society, especially a wave of major urban riots and a surge in violent crime, led to major gains in 1966, and to Nixon's election in the chaotic 1968 election. The Democrats became deeply divided on the Vietnam war (which did not divide the GOP), and on issues of race, when Alabamian George C. Wallace set up a third party that carried much of the deep South.

As Goldwater faded to a lesser role after 1964, a new conservative hero emerged: in the largest and most trendy state film star Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California in 1966 and reelected in 1970.

With the rise of conservatism the national Republican Party became more ideologically homogeneous. This change occurred as conservative politicians and voters joined the party and their liberal counterparts abandoned the GOP. Events in New York State during the 1960s and 1970s facilitated this transformation. Here, ideological conservatives formed a third party for the express purpose of changing a state GOP that both symbolized and contributed to the national GOP's liberal viewpoint. The Conservative Party relied on the state's unique election law to crash the New York GOP, either by forcing its way in or by imposing a lethal electoral price. The GOP-Conservative Party relationship began in 1962 at sword's point but achieved a high degree of harmony in 1980. Initially, New York Republicans, led by Governor Nelson Rockefeller, successfully marginalized the new party. As the conservative movement matured, however, the balance of power began to shift. When Nixon was elected president in 1968, the Conservative Party gained an external ally who proved invaluable. The third party achieved partial acceptance in 1970 with the election of James Buckley to the Senate. For much of the ensuing decade, however, Conservatives struggled with success suffering a series of damaging setbacks. Only in the late 1970s, did the party recover when it embraced a more modest agenda. Finally, the 1980 election settled the overall contours of the relationship between the two parties. Conservatives formed their party to force the state GOP to the right, to drive liberal Republicans from office, and allow ideologically conservative national Republicans to succeed in the state. By 1980, it had achieved these goals changing the nature of politics in the state. This resolution affected politics beyond the state by diminishing the importance of ideological liberals in the national GOP, thus freeing a more ideologically consistent national Republican Party to promote the rise of conservatism.[12]

Realignment: The South becomes Republican[edit]

In the century after Reconstruction ended in 1877, the white South identified with the Democratic Party. The Democrats' lock on power was so strong, the region was called the "Solid South." The Republicans controlled certain parts of the Appalachian mountains, but they sometimes did compete for statewide office in the border states. Before 1964, the southern Democrats saw their party as the defender of the southern way of life, which included a respect for states' rights and an appreciation for traditional southern values. They repeatedly warned against the aggressive designs of Northern liberals and Republicans, as well as the civil rights activists they denounced as "outside agitators." Thus there was a serious barrier to becoming a Republican.

However, since 1964, the Democratic lock on the South has been broken. The long-term cause was that the region was becoming more like the rest of the nation and could not long stand apart in terms of racial segregation. Modernization that brought factories, businesses, and cities, and millions of migrants from the North; far more people graduated from high school and college. Meanwhile the cotton and tobacco basis of the traditional South faded away, as former farmers moved to town or commuted to factory jobs.

The immediate cause of the political transition involved civil rights. The civil rights movement caused enormous controversy in the white South with many attacking it as a violation of states' rights. When segregation was outlawed by court order and by the Civil Rights acts of 1964 and 1965, a die-hard element resisted integration, led by Democratic governors Orval Faubus of Arkansas, Lester Maddox of Georgia, and, especially George Wallace of Alabama. These populist governors appealed to a less-educated, blue-collar electorate that on economic grounds favored the Democratic party, but opposed segregation. After passage of the Civil Rights Act most Southerners accepted the integration of most institutions (except public schools). With the old barrier to becoming a Republican removed, traditional Southerners joined the new middle class and the Northern transplants in moving toward the Republican party. Integration thus liberated Southern politics, just as Martin Luther King had promised. Meanwhile the newly enfranchised black voters supported Democratic candidates at the 85-90% level.

The South's transition to a Republican stronghold took decades. First the states started voting Republican in presidential elections--the Democrats countered that by nominating Southerners who could carry some states in the region, such as Jimmy Carter in 1976 and 1980, and Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996; the strategy did not work with Al Gore in 2000, or John Edwards in 2004. Then the states began electing Republican senators to fill open seats caused by retirements, and finally governors and state legislatures changed sides. Georgia was the last state to fall, with Sonny Perdue taking the governorship in 2002. Republicans aided the process with systematic gerrymandering that protected the African American and Hispanic vote (as required by the Civil Rights laws), but split up the remaining white Democrats so that Republicans mostly would win. In 2006 the Supreme Court endorsed nearly all of the redistricting engineered by Tom DeLay that swung the Texas Congressional delegation to the GOP in 2004.

In addition to its white middle class base, Republicans attracted strong majorities from the evangelical Christian vote, which had been nonpolitical before 1980. The national Democratic Party's support for liberal social stances such as abortion drove many former Democrats into a Republican party that was embracing the conservative views on these issues. Conversely, liberal Republicans in the northeast began to join the Democratic Party. In 1969 in The Emerging Republican Majority, Kevin Phillips, argued that support from Southern whites and growth in the Sun Belt, among other factors, was driving an enduring Republican electoral realignment. Today, the South is again solid, but the reliable support is for Republican presidential candidates. Exit polls in 2004 showed that Bush led Kerry by 70-30% among whites, who comprised 71% of the Southern voters. Kerry had a 90-9% lead among the 18% of the voters who were black. One third of the Southerners said they were white evangelicals; they voted for Bush by 80-20%. [1]

Reagan[edit]

Ronald Reagan was elected President in the 1980 election by a landslide vote, not predicted by most voter polling. Running on a "Peace Through Strength" platform to combat the Communist threat and massive tax cuts to revitalize the economy, Reagan's strong but genial persona proved too much for the ineffective and sour Carter. Reagan's election also gave Republicans control of the Senate for the first time in decades. Dubbed the "Reagan Revolution" he fundamentally altered several long standing debates in Washington, namely dealing with the Soviet threat and reviving the economy. His election saw the conservative wing of the party gain control. While reviled by liberal opponents in his day, his proponents contend his programs provided unprecedented economic growth, and spurred the collapse of the former Soviet Union. Currently regarded as one of the most popular and successful presidents in the modern era (1960-present.) He inspired Conservatives to greater electoral victories by being re-elected in a landslide against Walter Mondale in 1984 but oversaw the loss of the Senate in 1986.

Recent Politics: 1992-present[edit]

The entry of billionaire Ross Perot into the 1992 election drained support and momentum from Bush, who was defeated by Arkansas governor Bill Clinton.

Hispanics[edit]

Hispanics, growing rapidly, surpassed the black population in numbers in the late 1990s. but their electoral impact was weakened by low turnout rates. A series of "wedge" issues emerged in the mid 1990s-- immigration reform, welfare reform, affirmative action, English as an official language -- and the antagonistic positions taken by Republicans toward Hispanics on those issues alienated Hispanics from the GOP. 1996 GOP nominee Bob Dole sacrificed the already tenuous appeal of the GOP toward Hispanics by embracing an anti-Hispanic position in an effort to appeal to WASP voters. In the end, the Dole strategy failed due to his inability to gain the support of white women. In the meantime, 72% of Hispanics voted for Democrat Bill Clinton, the highest percentage ever. In four states with large Hispanic elements, including California, Hispanics were a key component of the Clinton victory margin. In Florida and Arizona, Hispanics helped steer those states from the Republican to the Democratic column. In Texas and Colorado, Hispanic support for Clinton contributed to the close election, even though Clinton lost. In New Mexico, the Hispanic vote was pivotal to the Clinton victory.[13] In 2000 George W. Bush made a systematic effort to appeal to Hispanic voters, and did well especially in Texas. By 2006, however, anti-immigration sentiment in the GOP caused a backlash among Hispanics.

GOP Name and the Elephant[edit]

The Republican party is known as the G.O.P.. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the first known reference to the Republican party as the "grand old party" came in 1876. The first use of the abbreviation G.O.P. is dated 1884. The symbol of the Republican party, an elephant, dates from an 1874 cartoon by Thomas Nast. In the early 20th century, the traditional symbol of the Republican Party in Midwestern states such as Indiana and Ohio was the eagle, as opposed to the Democratic rooster. This symbol still appears on Indiana and Oklahoma ballots.

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ Gould (2003) pp 14-15; republicanism is explored in depth by Foner (1970).

- ↑ There is also a myth that the town of Exeter, New Hampshire was first by six months, but nothing came of the secret meeting there and scholars dismiss the claim.

- ↑ There was some strength in border cities such as St. Louis, Louisville, Wheeling, and Baltimore.

- ↑ Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. 1993.

- ↑ They included Nathaniel P. Banks of Massachusetts, Kinsley Bingham of Michigan, William H. Bissell of Illinois, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, Samuel J. Kirkwood of Iowa, Ralph Metcalf of New Hampshire, Lot Morrill of Maine, and Alexander Randall of Wisconsin).

- ↑ The senators included Bingham and Hamlin, as well as James R. Doolittle of Wisconsin, John P. Hale of New Hampshire, Preston King of New York, Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, and David Wilmot of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Kleppner (1979) has extensive detail on the voting behavior of groups.

- ↑ Goodwyn 2005

- ↑ Marjorie Freeman Harrison, "Machine Politics Suburban Style: J. Russel Sprague and the Nassau County (New York) Republican Party at Midcentury." PhD dissertation Columbia U. 2005. 388 pp. DAI 2005 66(5): 1925-A. DA3174807

- ↑ John Morrison McLarnon, "Ruling Suburbia: A Biography of the McClure Machine of Delaware County, Pennsylvania." PhD dissertation U. of Delaware 1998. 616 pp. DAI 1998 58(12): 4780-A. DA9819160

- ↑ Brennan (1995) p, 59

- ↑ Timothy J. Sullivan, "Crashing the Party: The New York State Conservative and Republican Parties, 1962-1980." PhD dissertation U. of Maryland, College Park 2003. 458 pp. DAI 2004 64(11): 4181-A. DA3112508

- ↑ Maurilio E. Vigil, "Hispanics and the 1996 Presidential Election." Latino Studies Journal 1998 9(1): 43-61. Issn: 1066-1344

KSF

KSF