Second Party System

From Citizendium - Reading time: 13 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 13 min

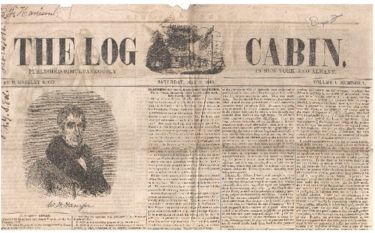

The Second Party System is the term that historians and political scientists give to the political system existing in the United States from about 1828 to 1854. It replaced the First Party System, and was followed by the Third Party System. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels of voter interest starting in 1828, as shown in election day turnout, rallies, partisan newspapers, and a high degree of personal loyalty to party. The major parties were the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, a coalition of National Republicans, and other opponents of Jackson, led by Henry Clay, along with Daniel Webster Minor parties that operated included the Anti-Masonic Party, which was an important innovator from 1827–34, the Liberty Party in 1840, the Free Soil Party in 1848 and 1852, and the Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s. The Second Party System reflected and shaped the political, social, economic and cultural currents of the Jacksonian Era.

Patterns[edit]

McCormick is most responsible for defining the system. He concluded [1]

- It was a distinct party system.

- It formed over a 15 year period that varied by state.

- It was produced by leaders trying to win the presidency, with contenders building their own national coalitions.

- Regional effects strongly affected developments, with the Adams forces strongest in New England, for example, and the Jacksonians in the Southwest.

- For the first time two-party politics was extended to the South and West (which had been one-party regions).

- In each region the two parties were about equal--the first and only party system showing this.

- Because of the regional balance it was vulnerable to region-specific issues (like slavery).

- The same two parties appeared in every state, and contested both the electoral vote and state offices.

- Most critical was the abrupt emergence of a two-party South in 1832-34 (mostly as a reaction against Van Buren).

- The Anti-Masonic party flourished in only those states with a weak second party.

- Methods varied somewhat but everywhere the party convention replaced the caucus.

- The parties had an interest of their own, in terms of the office-seeking goals of party activists.

- The System brought forth a new, popular campaign style.

- Close elections brought out the voters (not charismatic candidates or particular issues).

- Party leaders formed the parties to some degree in their own image.

Leaders[edit]

Among the best-known Democratic leaders were: Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John C. Calhoun, James K. Polk, Lewis Cass. The more well-known Whigs were: Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, William H. Seward, John Quincy Adams, and Thurlow Weed.

The 1824 presidential election, operated without political parties, came down to a four-man race. Each candidate (Henry Clay, William Crawford, Andrew Jackson, and John Quincy Adams), all of whom were nominally Democratic Republicans, had a regional base of support involving factions in the various states. With no electoral college majority, the choice devolved on the House of Representatives. Clay was not among the three finalists, but as Speaker of the House he negotiated the settlement. The House elected John Quincy Adams in spite of Jackson's more numerous popular votes and electoral votes. Adams immediately chose Clay as his Secretary of State. Jackson and his followers loudly denounced the selection of Clay as the "Corrupt Bargain." The Adams-Clay wing of the Democratic-Republican Party became known as the National Republicans, while the Jackson wing of the Democratic-Republican party became known as the Democratic Party.

During the years between 1825 and 1828, Jackson set about building up his organization for the election of 1828. Campaigning vigorously, and appealing both to local militia companies and to state political factions, Jackson assembled a coalition that ousted Adams in 1828. Martin Van Buren, brilliant leader of New York politics, was Jackson's key aide, bringing along the large electoral votes of Virginia and Pennsylvania. Van Buren's reward was appointment as Secretary of State and later nomination and election to the vice presidency as heir to the Jacksonian tradition.

Jackson: Bank war and Spoils System[edit]

Jackson considered himself a reformer. More exactly he was committed to the old ideals of Republicanism, and bitterly opposed anything that smacked of special favors for special interests. While Jackson never engaged in a duel as president, he had shot political opponents before and was just as determined to destroy his enemies on the battlefields of politics. The Second Party System came about primarily because of Jackson's determination to destroy the Second Bank of the United States. Headquartered in Philadelphia, with offices in major cities around the country, the federally chartered Bank operated somewhat like a central bank (like the Federal Reserve System a century later). Local bankers and politicians annoyed by the controls exerted by Nicholas Biddle grumbled loudly. Jackson did not like any banks (paper money was anathema to the Old Republican; they believed God intended only gold and silver ["specie"] to circulate.) After Herculean battles with Henry Clay, the chief protagonist, Jackson finally broke Biddle's bank.

Jackson continued to attack the banking system. His Specie Circular of July 1836 rejected paper money issued by banks (it could no longer be used to buy federal land), insisting on gold and silver coins. Most businessmen and bankers (but not all) went over to the Whig party, and the commercial and industrial cities became Whig strongholds. Jackson meanwhile became even more popular with the subsistence farmers and day laborers who distrusted bankers and finance.

Jackson systematically used the federal patronage system, what was called the Spoils System. Jackson not only rewarded past supporters; he promised future jobs if local and state politicians joined his team. As Syrett explains: When Jackson became President, he implemented the theory of rotation in office, declaring it "a leading principle in the republican creed."[2] He believed that rotation in office would prevent the development of a corrupt civil service. On the other hand, Jackson's supporters wanted to use the civil service to reward party loyalists to make the party stronger. In practice, this meant replacing civil servants with friends or party loyalists into those offices. The spoils system did not originate with Jackson. It originated under Thomas Jefferson when he removed Federalist office-holders after becoming president. Jackson did not throw out everyone (only about 20%).[3] While Jackson did not start the spoils system, he did encourage its growth and it became a central feature of the Second Party System, as well as the Third Party System, until it ended in the 1890s. As one historian explains:

- "Although Jackson dismissed far fewer government employees than most of his contemporaries imagined and although he did not originate the spoils system, he made more sweeping changes in the Federal bureaucracy than had any of his predecessors. What is even more significant is that he defended these changes as a positive good. At present when the use of political patronage is generally considered an obstacle to good government, it is worth remembering that Jackson and his followers invariably described rotation in public office as a "reform." In this sense the spoils system was more than a way to reward Jackson's friends and punish his enemies; it was also a device for removing from public office the representatives of minority political groups that Jackson insisted had been made corrupt by their long tenure."[4]

Modernizing Whigs[edit]

Meanwhile economic modernizers, bankers, businessmen, commercial farmers, many of whom were already National Republicans, and Southern planters angry at Jackson's handling of the Nullification crisis were mobilized into a new anti-Jackson force; they called themselves Whigs. In the northeast, a moralistic crusade against the highly secretive Masonic order matured into a regular political party, the Anti-Masons, which soon combined with the Whigs. Jackson fought back by aggressive use of federal patronage, by timely alliances with local leaders, and with a rhetoric that identified the Bank and its agents as the greatest threat to the republican spirit. Eventually his partisans called themselves "Democrats." The Whigs had an elaborate program for modernizing the economy. To stimulate the creation of new factories, they proposed a high tariff on imported manufactured goods. The Democrats used rhetoric that alleged the Whig programs that would fatten the rich; the tariff should be low--for "revenue only" (thus not to foster manufacturing). Whigs argued that banks and paper money were needed; no honest man wants them, countered the Democrats. Public works programs to build roads, canals and railroads would give the country the infrastructure it needed for rapid economic development, said the Whigs. We don't want that kind of complex change, said the Democrats. We want more of the same--especially more farms for ordinary folks (and planters) to raise the families in the good old traditional style. More land is needed for that, Democrats said, so they pushed for expansion south and west. Jackson conquered Florida for the US. Over intense Whig opposition, his political heir, James Polk (1844-48) added Texas, the Southwest, California, and Oregon. Next on the Democratic agenda would be Cuba.

In most cities the rich men were solidly Whig--85-90% of the men worth over $100,000 in Boston and New York City voted Whig.[5]. In rural America, the Whigs were stronger in market towns and commercial areas, and the Democrats stronger on the frontier and in more isolated areas. Ethnic and religious communities usually went the same way, with Irish and German Catholics heavily Democratic, and pietistic Protestants more Whiggish. [6].

The parties[edit]

Democratization[edit]

Gienapp (1982) points out that the American political system underwent fundamental change after 1820 under the rubric of Jacksonian Democracy. While Jackson himself did not initiate the changes he took advantage in 1828 and symbolized many of the changes. For the first time politics assumed a central role in voters' lives. Before then deference to upper class elites, and general indifference most of the time, characterized local politics across the country. The suffrage laws were not at fault for they allowed mass participation; rather few men were interested in politics before 1828, and fewer still voted or became engaged because politics did not seem important. Changed followed the psychological shock of the panic of 1819, and the 1828 election of Andrew Jackson, with his charismatic personality and controversial policies. By 1840, Gienapp argues, the revolution was complete: "With the full establishment of the second party system, campaigns were characterized by appeals to the common man, mass meetings, parades, celebrations, and intense enthusiasm, while elections generated high voter participation. In structure and ideology, American politics had been democratized." [7]

Democratic Strategies[edit]

The Whigs built a strong party organization in most states; they were weak only on the frontier. The Whigs used newspapers effectively and soon adopted exciting campaign techniques that lured 75 to 85% of the eligible voters to the polls. Abraham Lincoln emerged early as a leader in Illinois—where he usually was bested by an even more talented politician, Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas was the dominant figure in the Democratic Party throughout the late 1840s and 1850s. While Douglas and the Democrats were somewhat behind the Whigs in newspaper work, they made up for this weakness by an emphasis on party loyalty. Anyone who attended a Democratic convention, from precinct level to national level, was honor bound to support the final candidate, whether he liked him or not. This rule produced numerous schisms, but on the whole the Democrats controlled and mobilized their rank and file more effectively than the Whigs did.

Whig weaknesses[edit]

The biggest problem for the Whigs was not lack of leadership or organization. Rather it was that they were always a close second. Party loyalty was strong, and it was hard to convert 48% of the vote into 51%. Clay was the towering leader of the party, but he repeatedly lost (in 1824, 1832, 1844). The Whigs had their most luck with famous generals (like William Henry Harrison, winner in 1840, and Zachary Taylor, winner in 1848), but even that did not always work (Harrison lost in 1836; Winfield Scott lost in 1852).

The Whig party's other fundamental weakness was its inability to take a position on slavery. As a coalition of Northern National Republicans and Southern Nullifiers, Whigs in each of the two regions held opposing views on slavery. Therefore, the Whig party was only able to conduct successful campaigns as long as the slavery issue was ignored. By the mid-1850s, the question of slavery dominated the political landscape, and the Whigs, unable to agree on an approach to the issue, began to disintegrate. A few Whigs lingered, claiming that, with the alternatives being a pro-Northern Republican party and a pro-Southern Democratic party, they were the only political party that could preserve the Union. In 1856, the remaining Whigs endorsed the Know-Nothing campaign of Millard Fillmore and in 1860 they endorsed the Constitutional Union ticket of John Bell, but, with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the Whig party ceased to exist.

Most of the prominent men in most towns and cities were Whigs, and they controlled local offices and judgeships, in addition to many state offices. Thus the outcome of the political process was mixed. In Springfield, Illinois, a strong Whig enclave in a Democratic region, poll books that show how individuals voted indicates the rise of the Whigs took place in 1836 in opposition to the presidential candidacy of Martin Van Buren and was consolidated in 1840. Springfield Whigs tend to validate historical studies elsewhere: they were largely native-born, either in New England or Kentucky, professional men or farm owners, and devoted to partisan organization. Abraham Lincoln's career mirrors the Whigs' political rise, but by the 1840's Springfield began to fall into the hands of the Democrats, as immigrants changed the city's political makeup. By the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln was barely able to win the city.[8]

Democrats dominant 1852[edit]

By the 1850s most Democratic party leaders had accepted many Whiggish ideas, and no one could deny the economic modernization of factories and railroads was moving ahead rapidly. The old economic issues died about the same time old leaders like Calhoun, Webster, Clay, Jackson and Polk passed from the scene. New issues, especially the questions of slavery, nativism and religion came to the fore. 1852 was the last hurrah for the Whigs; everyone realized they could win only if the Democrats split in two. With the healing of the Free Soil revolt after 1852, Democratic dominance seemed assured. The Whigs went through the motions, but both rank and file and leaders quietly dropped out. The Third Party System was ready to emerge.

See also[edit]

- Nineteenth century American election campaigns

- First Party System

- Third Party System

- Whig Party

- Democratic Party (United States), history

Bibliography[edit]

- Altschuler, Glenn C. and Stuart M. Blumin. "Limits of Political Engagement in Antebellum America: A New Look at the Golden Age of Participatory Democracy" Journal of American History (Dec 1997) vol. 84 pp. 878–79 in JSTOR

- Altschuler, Glenn C. and Stuart M. Blumin. Rude Republic: Americans and Their Politics in the Nineteenth Century (2000) online edition

- Baker, Jean. Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century’’ (1983)

- Benson, Lee. The Concept of Jacksonian Democracy: New York as a Test Case. 1961

- Beveridge, Albert J. Abraham Lincoln, 1809–1858 vol. 1, ch. 4–8 1928 online edition of vol 1

- Brown, Thomas. Politics and Statesmanship: Essays on the American Whig Party 1985 online

- Brown, David. "Jeffersonian Ideology And The Second Party System" Historian, Fall, 1999 v62#1 pp 17-44 online edition

- Carwardine Richard. Evangelicals and Politics in Antebellum America Yale University Press, (1993)

- Cole, Arthur Charles. The Whig Party in the South 1913 online edition

- Dinkin, Robert J. Campaigning in America: A History of Election Practices. (Greenwood 1989) online edition

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970) online edition influential analysis of ideas

- Formisano, Ronald P. "The 'Party Period' Revisited," The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 1 (Jun., 1999), pp. 93-120 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. "Toward a Reorientation of Jacksonian Politics: A Review of the Literature, 1959-1975," The Journal of American History Vol. 63, No. 1 (Jun., 1976), pp. 42-65 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. ". The Invention of the Ethnocultural Interpretation," The American Historical Review, Vol. 99, No. 2 (Apr., 1994), pp. 453-477 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. "The New Political History and the Election of 1840," Journal of Interdisciplinary History Vol. 23, No. 4 (Spring, 1993), pp. 661-682 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. "Political Character, Antipartyism, and the Second Party System," American Quarterly (winter 1969) vol. 21 pp. 683–709 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. "Deferential-Participant Politics: The Early Republic's Political Culture, 1789–1840," American Political Science Review (June 1974) vol. 68 pp. 473–87 in JSTOR

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s 1983

- Hammond, Bray. Banks and Politics in America from the Revolution to the Civil War (1960), Pulitzer prize; the standard history. Pro-Bank

- Hammond, Bray. "Jackson, Biddle, and the Bank of the United States" The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 7, No. 1 (May, 1947), pp. 1-23 in JSTOR

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840 (1969) excerpt and text search

- Holt, Michael F. Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln 1992

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War, 1999 online; the standard history in 1000 pages

- Holt, Michael F. "The Antimasonic and Know Nothing Parties," in History of U.S. Political Parties, ed. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. (4 vols., New York, 1973), I, 575-620.

- Howe, Daniel Walker. "The Evangelical Movement and Political Culture during the Second Party System" Journal of American History (March 1991)vol. 77 pp. 1216–39 in JSTOR

- Howe, Daniel Walker. The Political Culture of the American Whigs (1984)

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (2007). 928pp; major survey of political and social history of the era

- Jaenicke, D.W. "The Jacksonian Integration of Parties into the Constitutional System," Political Science Quarterly, (1986), 101:65-107. fulltext in JSTOR

- Jensen, Richard. “Second Party System," in Encyclopedia of the United States in the Nineteenth Century (Scribner's, 2001)

- Keller, Morton. America's Three Regimes: A New Political History (2007) 384pp.

- Kruman, Marc W. "The Second Party System and the Transformation of Revolutionary Republicanism," Journal of the Early Republic (Winter 1992) vol. 12 pp. 509–37 in JSTOR

- Marshall, Lynn. "The Strange Stillbirth of the Whig Party," American Historical Review (Jan 1967) vol. 72 pp. 445–68 in JSTOR

- McCarthy, Charles. The Antimasonic Party: A Study of Political Anti-Masonry in the United States, 1827-1840, in the Report of the American Historical Association for 1902 (1903)

- McCormick, Richard P. The Party Period and Public Policy: American Politics from the Age of Jackson to the Progressive Era. (1986) excerpt and text search

- McCormick, Richard P. The Second American Party System: Party Formation in the Jacksonian Era (1966) highly influential

- McCormick, Richard P. "Political Development and the Party System," in W. N. Chambers and W. D. Burnham, eds. The American Party Systems (1967)

- Meyers, Marvin. The Jacksonian Persuasion: Politics and Belief (1957)

- Mueller, Henry R. The Whig Party in Pennsylvania (1922) online

- Nevins, Allan. The Evening Post: A Century of Journalism (1922) online edition

- Pessen, Edward, ed. The Many-Faceted Jacksonian Era: New Interpretations (1977) online edition articles by scholars

- Pessen, Edward. Jacksonian America: Society, Personality, and Politics 1978

- Ratcliffe, Donald J. The Politics of Long Division: The Birth of the Second Party System in Ohio, 1818-1828. Ohio State U. Press, 2000. 455 pp.

- Remini, Robert V. Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party 1959 online edition

- Remini, Robert V. Henry Clay: Statesman for the Union 1991 standard biography.

- Remini, Robert V. Daniel Webster 1997 , standard biography excerpt and text search

- Remini, Robert V. Andrew Jackson (3 vol and 1 vol editions), standard biography

- Riddle, Donald W. Lincoln Runs for Congress (1948) online

- Sellers, Charles. The Market Revolution: Jacksonian America, 1815-1846 (1991) online edition highly influential synthesis

- Shade, William G. "The Second Party System," Paul Kleppner ed. Evolution of American Electoral Systems 1983

- Shade, William G. Democratizing the Old Dominion: Virginia and the second party system, 1824-1861 1996 online at ACLS e-books

- Sharp, James Roger. The Jacksonians Versus the Banks: Politics in the States after the Panic of 1837 (1970) online edition

- Silbey, Joel H. The American Political Nation, 1838–1893 1991 online

- Van Deusen, Glyndon. "The Whig Party" in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed. History of U.S. Political Parties 1973 vol 1 pp. 331–63

- Syrett, Harold C. Andrew Jackson: His Contribution to the American Tradition (1953) online

- Van Deusen, Glyndon G. Thurlow Weed, Wizard of the Lobby (1947) online edition

- Vaughn, William Preston. The Antimasonic Party in the United States, 1826-1843. (1983)

- Watson, Harry L. Liberty and Power: The Politics of Jacksonian America (1990) influential short synthesis

- Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln 2005, influential long narrative

- Wilentz, Sean. "On Class and Politics in Jacksonian America" Reviews in American History, Vol. 10, No. 4, (Dec., 1982) pp. 45-63 in JSTOR

- Wilson, Major L. Space, Time, and Freedom: The Quest for Nationality and the Irrepressible Conflict, 1815-1861 (1974)online edition intellectual history of Whigs and Democrats

- Winkle, Kenneth J. "The Second Party System in Lincoln's Springfield." Civil War History (1998) 44(4): 267-284. Issn: 0009-8078 Fulltext online in Swetswise

Primary sources[edit]

- Blau, Joseph L. ed. Social Theories of Jacksonian Democracy: Representative Writings of the Period 1825-1850 (1947), 386 pages of excerpts

- Hammond, J. D. History of Political Parties in the State of New York (2 vols, 1842). vol 1 online; vol 3: 1841-47 (1848) online

- Howe, Daniel Walker. The American Whigs: An Anthology (1973) online

- Silbey, Joel H., ed. The American party battle: election campaign pamphlets, 1828-1876 (2 vol 1999) in ACLS E-Books online edition vol 1; also online edition vol 2

External links[edit]

- American Political History Online links

- Michael Holt, The Second American Party System, short topical essays

- "The Second American Party System and the Tariff:

KSF

KSF