Spanish missions in California

From Citizendium - Reading time: 52 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 52 min

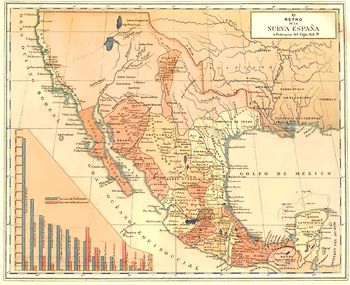

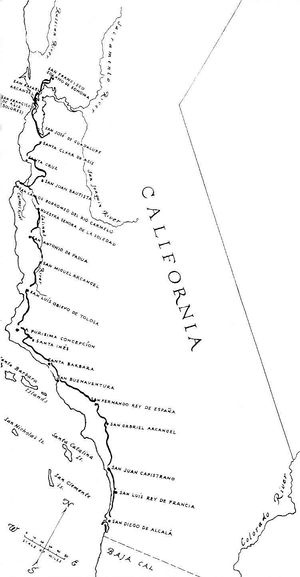

A map depicting New Spain around the turn of the 19th century. The California missions were situated within, and exerted influence over, the area identified in the upper left as "Nueva California," or "New" California.[1][2] A map depicting New Spain around the turn of the 19th century. The California missions were situated within, and exerted influence over, the area identified in the upper left as "Nueva California," or "New" California.[1][2]

| |

| Franciscan Establishments (1769–1823) | |

|---|---|

| Mission San Diego de Alcalá, founded in 1769 | |

| Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, founded in 1770 | |

| Mission San Antonio de Padua, founded in 1771 | |

| Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, founded in 1771 | |

| Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, founded in 1772 | |

| Mission San Francisco de Asís, founded in 1776 | |

| Mission San Juan Capistrano, founded in 1776 | |

| Mission Santa Clara de Asís, founded in 1777 | |

| Mission San Buenaventura, founded in 1782 | |

| Mission Santa Barbara, founded in 1786 | |

| Mission La Purísima Concepción, founded in 1787 | |

| Mission Santa Cruz, founded in 1791 | |

| Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, founded in 1791 | |

| Mission San José, founded in 1797 | |

| Mission San Juan Bautista, founded in 1797 | |

| Mission San Miguel Arcángel, founded in 1797 | |

| Mission San Fernando Rey de España, founded in 1797 | |

| Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, founded in 1798 | |

| Mission Santa Inés, founded in 1804 | |

| Mission San Rafael Arcángel, founded in 1817 | |

| Mission San Francisco Solano, founded in 1823 | |

The Spanish missions in California consisted of twenty-one religious outposts (along with their associated dependencies) established by Spaniards of the Franciscan Order between 1769 and 1823. The mission outposts were situated along a 600-mile trail dubbed El Camino Real, or "The Royal Highway." Considered by the Spanish Empire to be the only viable method of spreading the Catholic faith among the local Native American populations, the missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to colonize the Pacific Coast region, and helped Spain enforce its 167-year-old claim to Alta California as established by Sebastián Vizcaíno in 1602. By the time that Spanish occupation efforts began in earnest in the late 1760s there were hundreds of tribes inhabiting the region, each with its own diverse culture and language. The settlers introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the region. European contact was a momentous event, which profoundly affected California's native peoples. Ultimately, the mission system failed in its objective to convert, educate, and "civilize" the indigenous population in order to transform the California natives into Spanish colonial citizens, and therefore did not provide the anticipated economic benefits as well. The missions' unique design cues had a lasting influence on California architecture. A combination of natural disasters and neglect caused most of the mission structures to fall into ruin, though nearly all have since been rebuilt or restored. The ownership of all but two of the missions was returned to the Catholic Church via Presidential proclamations; Mission La Purísima Concepción and Mission San Francisco Solano are administered by the California Department of Parks and Recreation as State Historic Parks. Today, the missions are among the state's oldest structures and the most-visited historic monuments.

History[edit]

Precontact[edit]

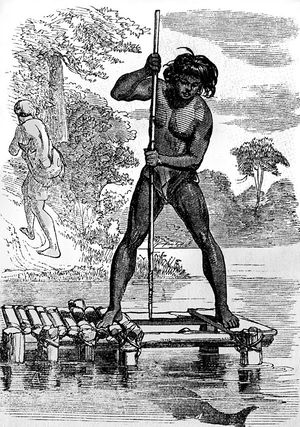

A California Indian spearing salmon.

Many native cultures built cone-shaped huts (often called kiichas or wikiups) made of willow branches covered with brush or mats made of tule leaves.[3][4]

The first human inhabitants of North America are thought to have made their homes among the southern valleys of California's coastal mountain ranges some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago; the earliest of these people are known only from archaeological evidence.[5][6][7] Over the course of thousands of years, California's diverse group of first settlers (later known as "Indians") evolved into hundreds of separate tribal groups, with an equally diverse range of languages, religions, dress, and other customs.[8][9] The tribes established comparatively peaceful cultures years before Spanish contact.

Early exploration and contact[edit]

By the time of the earliest European contacts, California was the most densely populated area north of Mexico.[10] Beginning in 1492 with the voyages of Christopher Columbus, the Kingdom of Spain sought to establish missions to convert the pagans in Nueva España ("New Spain," consisting of the Caribbean, Mexico and most of what today is the Southwestern United States) to Roman Catholicism, in order to facilitate colonization of these lands awarded to Spain by the Catholic Church, including that region known as Alta California.[11][12][13][14] However, it was not until 1741—the time of the Vitus Bering expedition, when the territorial ambitions of Tsarist Russia towards North America became known—that King Philip V felt such installations were necessary in Upper California.[15][16][17] California represents the "high-water mark" of Spanish expansion in North America, it being the last and northernmost colony on the continent.[18] The mission system arose in part from the need to control Spain's ever-expanding holdings in the New World. Realizing that the colonies would require a literate population base that the mother country could not supply, the government (with the cooperation of the Church) established a network of missions with the goal of converting the natives to Christianity; the aim was to make converts and tax paying citizens of the indigenous peoples they conquered.[19] In order to become Spanish citizens and productive inhabitants, the native Americans were required to learn Spanish language and vocational skills along with Christian teachings.[20] Estimates for the precontact native population in California have been based on a number of different sources (and therefore vary substantially), but indigenous peoples may have numbered as high as 300,000, divided into more than 100 separate tribes or nations.[21][22][23]

On January 29, 1767 King Charles III ordered the Jesuits, who had established a chain of fifteen missions throughout Baja California, forcibly expelled and returned to the home country.[24] Visitador General José de Gálvez engaged the Franciscans, under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, to take charge of those outposts on March 12, 1768.[25] The padres closed or consolidated several of the existing settlements, and also founded La Misión San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá (the only Franciscan mission in all of Baja California) and the nearby Visita de la Presentación in 1769. This plan, however, was changed within a few months after Gálvez received the following orders: "Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain." [26] It was thereupon decided to call upon the priests of the Dominican Order to take charge of the Baja California missions in order to allow the Franciscans to concentrate on founding new missions in Alta California.[27]

Founding[edit]

Expeditions[edit]

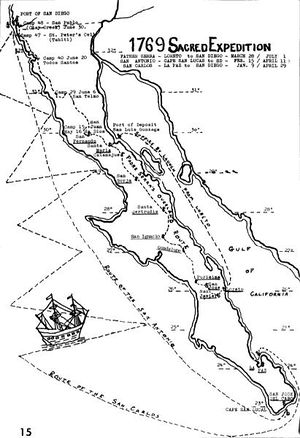

A map of the Sacred Expeditions of 1769, showing the routes of the San Antonio and the San Carlos, and the land route followed by Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà from Loreto.

The founding of Mission San Diego de Alcalá, July 16, 1769.

Prior to 1754, grants of mission lands were made directly by the Spanish Crown; however, given the remote locations and the inherent difficulties in communicating with the territorial governments, power was transferred to the viceroys of New Spain to grant lands and establish missions in North America.[28] The twenty-one Alta California missions were established along the northernmost section of California's El Camino Real (Spanish for "The Royal Highway," though often referred to as "The King's Highway", christened in honor of King Charles III of Spain), much of which is now U.S. Route 101 and several Mission Streets. The mission planning was begun in 1767 under the leadership of Fray Junípero Serra, O.F.M. (who, in 1767, along with his fellow priests, had taken control over a group of missions in Baja California previously administered by the Jesuits).

The Franciscans' first campaign into Upper California commenced in January of 1769. Four separate expeditions were undertaken in order to lessen the risk of failure,as well as to gain practical knowledge of both routes. Two groups marched out initially over land from the settlement at Loreto and two others departed aboard the only available vessels, the packet boats (small boats designed for the transportation of freight, passengers, and domestic mail) San Antonio and San Carlos (which sailed from the port of Cabo San Lucas and La Paz, respectively).[29] San Carlos shaped a course for San Diego on January 9, while San Antonio set sail on February 15.[30] The first land excursion set out from the settlement at Velicatá (some 200 miles south of Ensenada) on March 24 under the spiritual leadership of Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén who, along with by Father Juan Crespí and a band of pilgrims, traveled under the protection of Captain Fernando Rivera, Lieutenant Pedro Fages, and twenty-five soldiers. Serra's party procured the necessary provisions from other missions situated along the Baja Peninsula and went forth on May 15.[31] San Antonio dropped anchor in San Diego on April 11, 1769; San Carlos, which had been reportedly "struggling with difficulties" including leaking water-casks, bad water, scurvy, and cold weather, did not arrive until April 29.[32] Almost the entire complement of both ships contracted scurvy, and out of some ninety sailors, soldiers, and mechanics, less than thirty survived. Lasuén's contingent arrived soon thereafter and immediately erected a permanent camp at what today is known as "Old San Diego." On June 29, Gaspar de Portolà (the first governor of Las Californias) arrived just two days ahead of the last band traveling under Serra, on July 1. On July 16, 1769, Father Serra raised a cross and held mass, thereby formally establishing the Mission of San Diego de Alcalá.[33]

Father Pedro Estévan Tápis proposed the establishment of a mission on one of California's Channel Islands in 1784, with either Santa Catalina or Santa Cruz Island (known as Limú to the inhabitants) being the most likely locations, the reasoning being that an offshore mission might have attracted potential converts who were not disposed to associate with a mainland outpost, and would have been an effective measure to restrict smuggling operations.[34] Though Governor José Joaquín de Arrillaga approved the plan the following year, an outbreak of sarampion (measles) that left some 200 natives dead, coupled with a scarcity of good lands and water, left the success of such a venture in doubt, and no attempt to found an island mission was ever made. In September, 1821 Father Mariano Payeras, "Comisario Prefecto" of the California missions, visited Cañada de Santa Ysabel as part of a plan to establish an entire string of inland missions, with the Santa Ysabel Asistencia as the "mother" mission. The plan never came to fruition, however. Work on the mission chain was concluded in 1823, even though Serra had died in 1784 (plans to establish a twenty-second mission in 1827 in Santa Rosa, where settlers from nearby Sonoma raised and slaughtered livestock at the fork of the Santa Rosa Creek and Matanzas Creek, were canceled).[35] Fray Lasuén took up the work after Serra's death and established nine more mission sites, from 1786 through 1798; others established the last three compounds, along with at least five asistencias.[36] At the peak of its development in 1832, the mission system controlled an area equal to approximately one-sixth of Alta California.[37] Two short-lived settlements, Mission Puerto de Purísima Concepción and Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer, though located on the California side of the Colorado River, were founded under the authority of the Arizona mission hierarchy and are therefore not included herein.

Site selection and layout[edit]

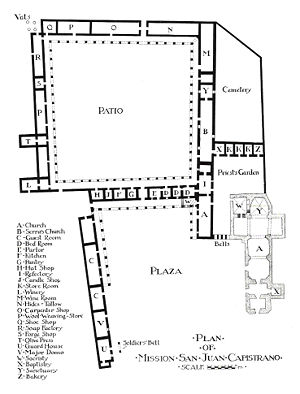

A plan view of the Mission San Juan Capistrano complex (including the footprint of the "Great Stone Church") prepared by architect Arthur B. Benton in 1916.[38]

In addition to the presidio (royal fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish sovereign to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. Asistencias ("satellite" or "sub" missions, sometimes referred to as "contributing chapels") were small-scale missions that, by definition, boasted all of the requisites of a mission, and that conducted regular Divine Service on days of obligation, but lacked a resident priest.[39] As with the missions, these settlements were typically established in areas with high concentrations of potential native converts.[40] The Spanish Californians had never strayed from the coast when establishing their settlements; Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad was located farthest inland, being only some thirty miles (48 kilometers) from the shore.[41] Each frontier station was forced to be self-supporting, as existing means of supply were inadequate to maintain a colony of any size. California was literally months away from the nearest base in colonized Mexico, and the cargo ships of the day were too small to carry more than a few months’ rations in their holds. In order to sustain a mission, the padres required the help of colonists or converted Native Americans, called neophytes, to cultivate crops and tend livestock in the volume needed to support a fair-sized establishment. The scarcity of imported materials, together with a lack of skilled laborers, compelled the Fathers to employ simple building materials and methods in the construction of mission structures.

Although the missions were considered temporary ventures by the Spanish hierarchy, the development of an individual settlement was not simply a matter of "priestly whim." The founding of a mission followed longstanding rules and procedures; the paperwork involved required months, sometimes years of correspondence, and demanded the attention of virtually every level of the bureaucracy. Once empowered to erect a mission in a given area, the men assigned to it chose a specific site that featured a good water supply, plenty of wood for fires and building material, and ample fields for grazing herds and raising crops.[42] The padres blessed the site, and with the aid of their military escort fashioned temporary shelters out of tree limbs or driven stakes, roofed with thatch or reeds (cañas). It was these simple huts that would ultimately give way to the stone and adobe buildings which exist to this day.

The first priority when beginning a settlement was the location and construction of the church (iglesia). The majority of mission sanctuaries were oriented on a roughly east-west axis to take the best advantage of the sun's position for interior illumination; the exact alignment depended on the geographic features of the particular site. Once the spot for the church had been selected, its position would be marked and the remainder of the mission complex would be laid out. The workshops, kitchens, living quarters, storerooms, and other ancillary chambers were usually grouped in the form of a quadrangle, inside which religious celebrations and other festive events often took place. The cuadrángulo was rarely a perfect square because the Fathers had no surveying instruments at their disposal and simply measured off all dimensions by foot. Some fanciful accounts regarding the construction of the missions claimed that underground tunnels were incorporated in the design, to be used as a means of emergency egress in the event of attack; however, no historical evidence (written or physical) has ever been uncovered to support these assertions.[43]

Mission Period (1769 – 1833)[edit]

The Missionaries as They Came and Went. Franciscans of the California missions donned gray habits, in contrast to the brown cassocks that are typically worn today.[44]

The first recorded baptisms in Alta California were performed in "The Canyon of the Little Christians." [45]

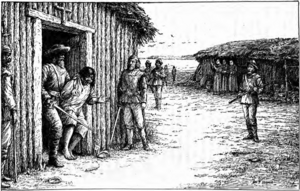

Frustrated First Baptism at San Diego. Fr. Serra and the other missionaries faced many difficulties in converting the Tipais and Ipais.

Captain Fernando Rivera y Moncada violated ecclesiastical asylum at Mission San Diego de Alcalá on March 26, 1776 when he forcibly removed a neophyte in direct defiance of the padres.[46][47]

Construction of the first Santa Bárbara mission.

On July 14, 1769 Gálvez sent the expedition of Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà from Loreto, in Baja California, to found a mission at San Diego and a presidio at Monterey, respectively.[48][49] As the planned colonization of Upper California was to be a spiritual as well as a military endeavor—with the founding of missions and conversion of Indians given at least equal weight to the establishment of presidios—the attempt to settle the northern country became known as the "Sacred Expedition." [50] En route to Monterey, Fathers Francisco Gómez and Juan Crespí came across a native settlement wherein two young girls were close to death: one, a baby said to be "dying at its mother's breast," the other a small girl suffering from severe burns. On July 22, Father Gómez baptized the baby, giving her the name "Maria Magdalena," while Father Crespí baptized the older child, naming her "Margarita;" these were the first recorded baptisms in Alta California.[51] The expedition's soldiers dubbed the spot Los Cristianos.[52] The group continued northward but missed Monterey Harbor and returned to San Diego on January 24, 1770. Near the end of 1771 the Portolà Expedition arrived at San Francisco Bay; between 1774 and 1791, the Spanish Crown sent forth a number of expeditions to explore the Pacific Northwest.

Each mission was to be turned over to a secular clergy and all the common mission lands distributed amongst the native population within ten years after its founding, a policy that was based upon Spain's experience with the more advanced tribes in Mexico, Central America, and Peru.[53] In time, it became apparent to Father Serra and his associates that the Indian tribes on the northern frontier in Alta California would require a much longer period of acclimatization.[54] None of the California missions ever attained complete self-sufficiency, and required continued (albeit modest) financial support from mother Spain.[55][56] Mission development was therefore financed out of El Fondo Piadoso de las Californias ("The Pious Fund of the Californias," which had its origin in 1697 and consisted of voluntary donations made by individuals and religious bodies in Mexico to members of the Society of Jesus) to enable the missionaries to propagate the Catholic Faith in the area then known as California. Starting with the onset of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810, this support largely disappeared and the missions and their converts were left on their own (as of 1800, native labor had made up the backbone of the colonial economy).[57] Arguably "the worst epidemic of the Spanish Era in California" was known to be the measles epidemic of 1806, wherein one-quarter of the mission Indian population of the San Francisco Bay area died of the measles or related complications between March and May of that year.[58] In 1811, the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico sent an interrogatorio (questionnaire) to all of the missions in Alta California regarding the customs, disposition, and condition of the Mission Indians.[59] The replies, which varied greatly in the length, spirit, and even the value of the information contained therein, were collected and prefaced by the Father-Presidente with a short general statement or abstract; the compilation was thereupon forwarded to the viceregal government.[60] The contemporary nature of the responses, no matter how incomplete or biased some may be, are nonetheless of considerable value to modern ethnologists.

Russian colonization of the Americas reached its southernmost point with the 1812 establishment of Fort Ross (krepost' rus), an agricultural, scientific, and fur-trading settlement located in present-day Sonoma County as an attempt to extend control to the federal territory of Alta California.[61][62] In November and December of 1818, several of the missions were attacked by Hipólito Bouchard, "California's only pirate." [63] A French privateer sailing under the flag of Argentina, Pirata Buchar (as he was known to the locals) worked his way down the California coast, conducting raids on the installations at Monterey, Santa Barbara, and San Juan Capistrano, with minimal success.[64] Upon hearing of the attacks, many mission priests (along with a few government officials) sought refuge at Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, the mission chain's most isolated outpost. Ironically, Mission Santa Cruz (though ultimately ignored by the marauders) was ignominiously sacked and vandalized by local residents who were entrusted with securing the church's valuables.[65]

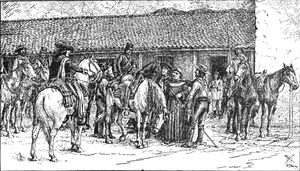

By 1819, Spain decided to limit its "reach" in the New World to Northern California due to the costs involved in sustaining these remote outposts; the northernmost settlement therefore is Mission San Francisco Solano, founded in Sonoma in 1823 at the direction of the Mexican government.[66] An attempt to found a twenty-second mission in Santa Rosa in 1827 was aborted.[67][68][69] As the Mexican republic matured, calls for the secularization ("disestablishment") of the missions increased.[70] José María de Echeandía, the first native Mexican to be elected Governor of Alta California, issued his "Proclamation of Emancipation" (or "Prevenciónes de Emancipacion") on July 25, 1826.[71] All Indians within the military districts of San Diego, Santa Barbara, and Monterey who were found qualified were freed from missionary rule and made eligible to become Mexican citizens. Those who wished to remain under mission tutelage were exempted from most forms of corporal punishment.[72][73] By 1830 even the neophyte populations themselves appeared confident in their own abilities to operate the mission ranches and farms independently; the padres, however, doubted the capabilities of their charges in this regard.[74] Ever-increasing immigration brought pressure to bear on local governments to seize the mission properties and disposses the natives in accordance with Echeandía's directive.[75] Despite the fact that Echeandía's emancipation plan met was met with little encouragement from the novices who populated the southern missions, he was nonetheless determined to test the scheme on a large scale at Mission San Juan Capistrano. To that end, he appointed a number of comisianados (commissioners) to oversee the emancipation of the Indians.[76] The Mexican government passed legislation on December 20, 1827 that mandated the expulsion of all Spaniards younger than sixty years of age from Mexican territories; Governor Echeandía nevertheless intervened on behalf of some of the missionaries in order to prevent their deportation once the law of took effect in California.[77]

Although Governor José Figueroa (who took office in 1833) initially attempted to keep the mission system intact, the Mexican Congress nevertheless passed An Act for the Secularization of the Missions of California on August 17, 1833.[78] The Act also provided for the colonization of both Alta and Baja California, the expenses of this latter move to be borne by the proceeds gained from the sale of the mission property to private interests.

Rancho Period (1834 – 1849)[edit]

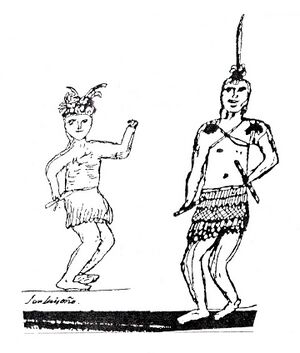

Pablo Tac, who lived at Mission San Luis Rey in the 1820s and 1830s, penned this drawing depicting two young men wearing skirts of twine and feathers with feather decorations on their heads, rattles in their hands, and (perhaps) painted decorations on their bodies.[79]

The forcible arrest and banishment of Reverend José de Jesus del Mercado from Mission Santa Clara in December, 1844.

By way of confiscation of the missions between 1834 and 1838 the approximately 15,000 resident neophytes lost the protection of the mission system, along with their stock and other movable property. Mission San Juan Capistrano was the very first to feel the effects of secularization the following year when, on August 9, 1834 Governor Figueroa issued his "Decree of Confiscation." [80] Nine other settlements quickly followed, with six more in 1835; San Buenaventura and San Francisco de Asís were among the last to succumb, in June and December of 1836, respectively.[81] The Franciscans soon thereafter abandoned most of the missions, taking with them most everything of value, after which the locals typically plundered the mission buildings for construction materials. In spite of this neglect, the Indian towns at San Juan Capistrano, San Dieguito, and Las Flores did continue on for some time under a provision in Gobernador Echeandía's 1826 Proclamation that allowed for the partial conversion of missions to pueblos.[82] In 1895 journalist and historian Charles Fletcher Lummis criticized the Act and its results, saying:

Disestablishment—a polite term for robbery—by Mexico (rather than by native Californians misrepresenting the Mexican government) in 1834, was the death blow of the mission system. The lands were confiscated; the buildings were sold for beggarly sums, and often for beggarly purposes. The Indian converts were scattered and starved out; the noble buildings were pillaged for their tiles and adobes...[83]

Also in 1835, the Mexican Congress resolved that Alta California and Baja California should be divided into a separate diocese.[84] However, it was not until the issuance of a papal bull on April 27, 1840 that Father Diego y Moreno assumed the position of bishop of the Californias.[85] Some three years later, on March 29, 1843, Governor Manuel Micheltorena issued a decree that restored the temporal management of twelve of the missions to the resident priests with the proviso that one-eighth (⅛) of all proceeds be paid into the public treasury.[86] Pío de Jesus Pico IV, the last Mexican Governor of Alta California, found upon taking office that there were few funds available with which to carry on the affairs of the province. He prevailed upon the assembly to pass a decree authorizing the renting or the sale of all mission property, reserving only the church, a curate's house, and a building for a courthouse.[87] The expenses of conducting the services of the church were to be provided from the proceeds, but there was no disposition made as to what should be done to secure the funds for that purpose.

In December of 1844 acting governor of Alta California José Antonio Castro ordered that the Reverend José de Jesus del Mercado be forcibly seized and removed from Mission Santa Clara due to the padre's "subversive conduct" with regard to the appropriation of mission property by Mexican settlers. After secularization, Father Presidente Narciso Durán transferred the missions' headquarters to Santa Barbara, thereby making Mission Santa Barbara the repository of some 3,000 original documents that had been scattered through the California missions. The Mission archive is the oldest library in the State of California that still remains in the hands of its founders, the Franciscans (Santa Barbara is the only mission in which they have maintained an uninterrupted presence). Beginning with the writings of Hubert Howe Bancroft, the library has served as a center for historical study of the missions for more than a century. According to one estimate, the native population in and around the missions proper was approximately 80,000 at the time of the confiscation; others claim that the statewide population had dwindled to approximately 100,000 by the early 1840s, due in no small part to the natives' exposure to European diseases for which they lacked immunity, and from the Franciscan practice of cloistering women in the convento and controlling sexuality during the child-bearing age (Baja California experienced a similar drop in the number of indigenous inhabitants resulting from Spanish colonization efforts there).[88][89]

Upon execution of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (which ended the Mexican–American War in 1848) the Mexican territory of Alta California became a United States territory, joining the Union in 1850.

Hugo Reid, an outspoken critic of the mission system and its effects on the native populations, visits Rancho Santa Anita circa 1850.[90]

California Statehood (1850 and beyond)[edit]

The western territory of Alta California was granted statehood on September 9, 1850.[91] The transfer of California to the United States left the former mission inhabitants without legal title to their land. Throughout his second term of office, Alta California governor Pío Pico sold off mission lands in order to help fill the State's depleted coffers.[92][93] Via the Act of September 30, 1850, the U.S. Congress appropriated funds to allow the President to appoint three Commissioners to study the California situation and "...negotiate treaties with the various Indian tribes of California." Treaty negotiations ensued during the period between March 19, 1851 and January 7, 1852, during which time the Commission interacted with 402 Indian chiefs and headmen (representing approximately one-third to one-half of the California tribes) and entered into eighteen treaties.[94] California Senator William M. Gwin's Act of March 3, 1851 created the Public Land Commission, whose purpose was to determine the validity of Spanish and Mexican land grants in California.[95][96] On February 19, 1853 Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany filed petitions for the return of all former mission lands in the state. Alemany's filings would not, however, see effect until some five years later (when, in March of 1858, James Buchanan initiated the first of a series of Presidential proclamations) that the process of restoration of mission lands to the Roman Catholic Church would commence.[97] Ownership of 1,051.44 acres (for all practical intents being the exact area of land occupied by the original mission buildings, cemeteries, and gardens) was subsequently conveyed to the Church, along with the Cañada de los Pinos (or College Rancho) in Santa Barbara County comprising 35,499.73 acres (143.6623 km²), and La Laguna in San Luis Obispo County, consisting of 4,157.02 acres (16.8229 km²).[98] As the result of a U.S. government investigation in 1873, a number of Indian reservations were assigned by executive proclamation in 1875. The commissioner of Indian affairs reported in 1879 that the number of Mission Indians in the state was down to around 3,000 with a total statewide population of less than 16,000 by 1900.[99][100]

The Mission Trail[edit]

Heavy freight movement was practical only via water. In order to facilitate overland travel, the mission settlements were situated approximately 30 miles (48 kilometers) apart, so that they were separated by one day's long ride on horseback (or three days on foot) along the 600-mile (966-kilometer) long "California Mission Trail." Father Lasuén is credited for having brought the concept to life in 1798 when he successfully argued that filling in the "spaces" along the route with additional outposts would provide much-needed rest stops, where travelers could take lodging in relative safety and comfort.[101] Tradition has it that the padres sprinkled mustard seeds along the trail in order to mark it with bright yellow flowers.[102]

An outline map illustrating the route of "El Camino Real" in 1821, along with the 21 Franciscan missions in Alta California. The road at this time was merely a horse and mule trail.

Missions in geographical order, north to south[edit]

- Mission San Francisco Solano; located in the present-day City of Sonoma — originally planned as an asistencia to Mission San Rafael Arcángel

- Mission San Rafael Arcángel; located in the present-day City of San Rafael — originally planned as an asistencia to Mission San Francisco de Asís

- Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores); located in the present-day City of San Francisco

- Mission San José; located in the present-day City of Fremont

- Mission Santa Clara de Asís; located in the present-day City of Santa Clara

- Mission Santa Cruz; located in the present-day City of Santa Cruz

- Mission San Juan Bautista; located in the present-day City of San Juan Bautista

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo; located south of the present-day City of Carmel-by-the-Sea

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad; located south of the present-day City of Soledad

- Mission San Antonio de Padua; located northwest of the present-day community of Jolon

- Mission San Miguel Arcángel; located in the present-day town of San Miguel

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa; located in the present-day City of San Luis Obispo

- Mission La Purísima Concepción; located northeast of the present-day City of Lompoc

- Mission Santa Inés; located in the present-day City of Solvang

- Mission Santa Barbara; located in the present-day City of Santa Barbara

- Mission San Buenaventura; located in the present-day City of Ventura

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España; located in the present-day community of Mission Hills (Los Angeles County)

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel; located in the present-day City of San Gabriel

- Mission San Juan Capistrano; located in the present-day City of San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia; located in the present-day City of Oceanside

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá; located in the present-day City of San Diego

Asistencias in geographical order, north to south[edit]

- Santa Rosa de Lima Asistencia, founded circa 1828; located in present-day City of Santa Rosa

- Santa Eulalia Asistencia, founded circa 1827; located in the present-day City of Rockville

- San Pedro y San Pablo Asistencia, founded in 1786; located in the present-day City of Pacifica

- Santa Paula Asistencia, founding date unknown; located in the present-day City of Santa Paula

- Santa Margarita de Cortona Asistencia, a visita (country chapel) founded in 1787; located in the present-day community of Santa Margarita

- Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles Asistencia, founded in 1784; located in the present-day City of Los Angeles

- San Antonio de Pala Asistencia ("Pala Mission"), founded in 1816; located in present-day eastern San Diego County

- Santa Ysabel Asistencia, founded in 1818; located in the present-day community of Santa Ysabel

Estancias in geographical order, north to south[edit]

The San Bernardino de Sena Estancia, today often referred to as "The Asistencia," circa 1880-1881.

The Santa Margarita de Cortona Asistencia in 1881.

Las Flores Estancia's "San Pedro Chapel" as it appeared around 1850.[103] The structure, along with its adjoining buildings, were constructed in 1823.[104]

The above illustration depicts the brutal death of Father Luís Jayme by the hands of angry natives at Mission San Diego de Alcalá, November 4, 1775.[105][106][107][108]

The funeral of Father Junípero in 1784.

Spanish Missionaries in California in the 18th century.

Listed below are the major estancias; the missions with which each ranch was associated are displayed in parentheses.

- Rancho Refugio (Santa Cruz)

- Rancho San Bartolome (San Antonio de Padua)

- Rancho San Miguelito (San Antonio de Padua)

- Rancho San Antonio de los Ajitos (San Antonio de Padua)

- Rancho San Benito (San Antonio de Padua)

- Rancho Aguage (San Miguel)

- Rancho Asunción (San Miguel)

- Rancho San Simeon (San Miguel)

- Rancho San Miguelito (San Luis Obispo)

- Rancho Arroyo Grande (San Luis Obispo)

- Santa Margarita (San Luis Obispo)

- Rancho de la Playa (San Luis Obispo)

- Rancho San Antonio (La Purísima)

- Rancho San Marcos (Santa Barbara)

- Rancho San Franciso Xavier (San Fernando)

- Rancho San Bernardino (San Gabriel)

- Rancho Santa Anita (San Gabriel)

- Santa Ana Estancia (San Juan Capistrano)

- Las Flores Estancia (San Luis Rey)

- Valle de San Luis (San Diego)

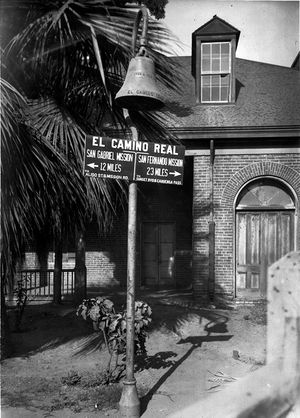

El Camino Real[edit]

The "Mission Bell Marker" system has existed on the historic route of El Camino Real (designated as California Historical Landmark #784, "As Father Serra Knew It and Helped Blaze It"),[109][110] since August 15, 1906, when the first of over 450 pole-mounted 85 pound (39 kilogram) cast iron markers was placed on the grounds of La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles in the Pueblo of Los Angeles. The bells were inscribed, "El Camino Real 1769-1906," the dates referencing the period between the founding of the first mission in 1769 and the dedication of the first bell. The work required to place a bell along each mile (1.6 kilometers) of the Highway and one at each mission was completed in 1913. Over time many bells were lost due to road reconstruction and theft. The bell marker system as originally envisioned was realized in early 2005 with the installation of new 18 inch (46 cm) diameter cast metal bell assemblies manufactured using the original molds to fabricate the bells.

Headquarters of the Alta California Mission System[edit]

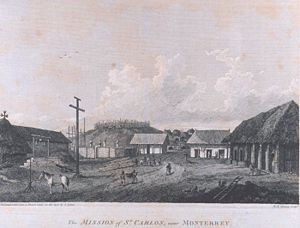

A drawing of Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo depicts the grounds as they appeared in November, 1792. From A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World.

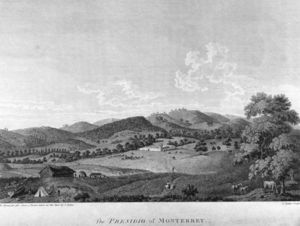

A drawing of The Presidio of Monterey depicts the "royal fort" as it appeared in November, 1792. From A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Round the World.

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá (1769–1771)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1771–1815)

- Mission La Purísima Concepción* (1815–1819)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1819–1824)

- Mission San José* (1824–1827)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo (1827–1830)

- Mission San José* (1830–1833)

- Mission Santa Barbara (1833–1846)

* Fathers Payeras and Durán remained at their resident missions during their terms as "Father-Presidente," therefore those settlements became the de facto headquarters (until 1833, when all mission records were permanently relocated to Santa Barbara).[111][112]

Military Districts[edit]

California during the Mission Period was divided into four military districts. Four presidios, strategically placed along the California coast, served to protect the missions and other Spanish settlements in Upper California.[113] Presidios were not fortresses, nor were they commanded or manned by trained military personnel (though presidial captains were often Spaniards with military experience); these men were more akin to militiamen than traditional soldiers.[114] Each of the comandancias (garrisons) functioned as a base of military operations for a specific region. Although independent of one another, a sort of unison or connection existed among the missions of each district, which were organized as follows:

- El Presidio Real de San Diego, founded on July 16, 1769 [115] — responsible for the defense of all installations located within the First Military District (the missions at San Diego, San Luis Rey, San Juan Capistrano, and San Gabriel);[116]

- El Presidio Real de Santa Bárbara, founded on April 12, 1782 [117] — responsible for the defense of all installations located within the Second Military District (the missions at San Fernando, San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, and La Purísima, along with El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles del Río de Porciúncula [Los Angeles]);[118]

- El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterey (El Castillo), founded on June 3, 1770 [119] — responsible for the defense of all installations located within the Third Military District (the missions at San Luis Obispo, San Miguel, San Antonio, Soledad, San Carlos, and San Juan Bautista, along with Villa Branciforte [Santa Cruz]);[120] and

- El Presidio Real de San Francisco, founded on December 17, 1776 [121] — responsible for the defense of all installations located within the Fourth Military District (the missions at Santa Cruz, San José, Santa Clara, San Francisco, San Rafael, and Solano, along with El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe).[122]

A view of Fort Ross in 1828.

El Presidio de Sonoma, or "Sonoma Barracks" (a collection of guardhouses, storerooms, living quarters, and an observation tower) was established in 1836 by Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo (the "Commandante-General of the Northern Frontier of Alta California") as a part of Mexico's strategy to halt Russian incursions into the region.[123] The Sonoma Presidio became the new headquarters of the Mexican Army in California, while the remaining presidios were essentially abandoned and, in time, fell into ruins.

An ongoing power struggle between church and state grew increasingly heated and lasted for decades. Originating as a feud between Father Serra and Pedro Fages (the military governor of Alta California from 1770 to 1774, who regarded the Spanish installations in California as military institutions first and religious outposts second), the uneasy relationship persisted for more than sixty years.[124][125] Dependent upon one another for their very survival, military leaders and mission padres nevertheless adopted conflicting stances regarding everything from land rights, the allocation of supplies, protection of the missions, the criminal propensities of the soldiers, and (in particular) the status of the native populations.[126]

Mission life[edit]

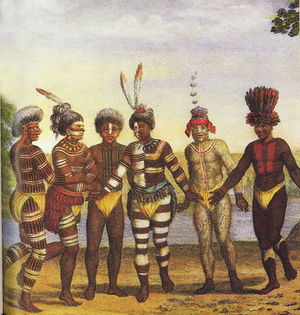

Georg von Langsdorff, an early visitor to California, sketched a group of Costeño dancers at Mission San José in 1806.[127][128]

Father Narciso Durán and his Indian musicians.

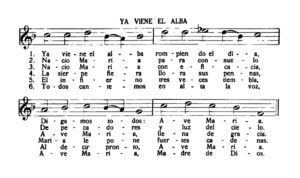

"Ya Viene El Alba" ("The Dawn Already Comes"), typical of the hymns sung at the missions.[129]

The Alta California missions were of a type known as reduccíones (reductions) or congregacíones (congregations), a concept developed in the late 16th century to be employed wherever the indigenous populations were not already concentrated in native pueblos; Indians were congregated around the mission proper through the use of various means, whereupon they were "reduced" from their "free, undisciplined" state and ultimately converted into civilized members of colonial society.[130][131][132] A total of 146 Friars Minor, all of whom were ordained as priests (and mostly Spaniards by birth) served in California between 1769–1845. 67 missionaries died at their posts (two as martyrs: Padres Luís Jayme and Andrés Quintana), while the remainder returned to Europe due to illness, or upon completing their ten-year service commitment.[133] As the rules of the Franciscan Order forbade friars to live alone, two missionaries were assigned to each settlement, sequestered in the mission's convento.[134] To these the governor assigned a guard of five or six soldiers under the command of a corporal, who generally acted as steward of the mission's temporal affairs, subject to the fathers' direction.[54]

Life at the California missions varied slightly throughout the entire system. Once a "gentile" was baptized, he or she became a neophyte, or new believer. This happened only after a brief period during which the initiates were instructed in the most basic aspects of the Catholic faith. But, while many natives were lured to join the missions out of curiosity and sincere desire to participate and engage in trade, many found themselves trapped once they received the sacrament of baptism. To the padres, a baptized Indian was no longer free to move about the country, but had to labor and worship at the mission under the strict observance of the fathers and overseers, who herded them to daily masses and labors. If an Indian did not report for their duties for a period of a few days a search was made (as required by Spanish law). If it was discovered that the individual left without permission, he or she was considered a runaway and subject to punishment.[135] A total of 20,355 natives were "attached" to the California missions in 1806 (the highest figure recorded during in the Mission Period); under Mexican rule the number rose to 21,066 (in 1824, the record year during the entire era of the Franciscan missions).[136]

Young native women were required to reside in the monjério (or "nunnery") under the supervision of a trusted Indian matron (the maestra, or "instructress") who bore the responsibility for their welfare and education.[137] Women only left the convent after they had been "won" by an Indian suitor and were deemed ready for marriage. Following Spanish custom, courtship took place on either side of a barred window. After the marriage ceremony the woman moved out of the mission compound and into one of the family huts.[138] These "nunneries" were considered a necessity by the priests, who felt the women needed to be protected from the men, both Indian and de razón. The cramped and unsanitary conditions the girls lived in contributed to the fast spread of disease and population decline. So many died at times that many of the Indian residents of the missions urged the fathers to raid new villages to supply them with more women. As of December 31, 1832 (the peak of the mission system's development) the mission padres had performed a combined total of 87,787 baptisms and 24,529 marriages, and recorded 63,789 deaths.[139]

Bells were vitally important to daily life at any mission. The bells were rung at mealtimes, to call the Mission residents to work and to religious services, during births and funerals, to signal the approach of a ship or returning missionary, and at other times; novices were instructed in the intricate rituals associated with the ringing the mission bells. The daily routine began with sunrise Mass and morning prayers, followed by instruction of the natives in the teachings of the Roman Catholic faith.[140] After a generous (by era standards) breakfast of atole (a traditional masa-based Mexican hot drink), the able-bodied men and women were assigned their tasks for the day. The women were committed to dressmaking, knitting, weaving, embroidering, laundering, and cooking, while some of the stronger girls would grind flour or carry adobe bricks (weighing 55 pounds, or 25 kilograms, each) to the men engaged in building. The men were tasked with a variety of jobs, having learned from the missionaries how to plow, sow, irrigate, cultivate, reap, thresh, and glean. In addition, they were taught to build adobe houses, tan leather hides, shear sheep, weave rugs and clothing from wool, make ropes, soap, paint, and other useful duties.

The work day was six hours, interrupted by dinner (lunch) around 11:00 a.m. and a two-hour siesta, and ended with evening prayers and the rosary, supper, and social activities. About 90 days out of each year were designated as religious or civil holidays, free from manual labor. The labor organization of the missions resembled a slave plantation in many respects.[141] Foreigners who visited the missions remarked at how the priests' control over the Indians appeared excessive, but necessary given the white men's isolation and numeric disadvantage.[142] Indians were not paid wages as they were not considered free laborers and, as a result, the missions were able to extract surplus value for the goods produced by the Mission Indians to the detriment of the other Spanish and Mexican settlers of the time who could not compete economically with the advantage of the mission system.[143] In recent years, much debate has arisen as to the actual treatment of the Indians during the Mission period, and many claim that the California mission system is directly responsible for the decline of the native cultures.[144] Evidence has now been brought to light that puts the Indians' experiences in a very different context.[145][146]

The missionaries of California were by-and-large well-meaning, devoted men...[whose] attitudes toward the Indians ranged from genuine (if paternalistic) affection to wrathful disgust. They were ill-equipped—nor did most truly desire—to understand complex and radically different Native American customs. Using European standards, they condemned the Indians for living in a "wilderness," for worshipping false gods or no God at all, and for having no written laws, standing armies, forts, or churches.[147]

Father-Presidents of the Alta California Mission System[edit]

A statue of Father Junípero Serra blessing a Juaneño Indian boy depicts the meeting of the two cultures; a replica of the original rough wooden cross raised during Mission San Juan Capistrano's founding once adorned this piece (left).[148]

- Father Junípero Serra (1769–1784)

- Father Francisco Palóu (presidente pro tempore) (1784–1785)

- Father Fermín Francisco de Lasuén (1785–1803)

- Father Pedro Estévan Tápis (1803–1812)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1812–1815)

- Father Mariano Payéras (1815–1820)

- Father José Francisco de Paula Señan (1820–1823)

- Father Vicente Francisco de Sarría (1823–1824)

- Father Narciso Durán (1824–1827)

- Father José Bernardo Sánchez (1827–1831)

- Father Narciso Durán (1831–1838)

- Father José Joaquin Jimeno (1838–1844)

- Father Narciso Durán (1844–1846)

The "Father-Presidente" was the head of the Catholic missions in Alta and Baja California. He was appointed by the College of San Fernando de Mexico until 1812, when the position became known as the "Commissary Prefect" who was appointed by the Commissary General of the Indies (a Franciscan residing in Spain). Beginning in 1831, separate individuals were elected to oversee Upper and Lower California.[149]

Mission industries[edit]

Two women grinding and crushing corn on the metate, or "mealing stone."

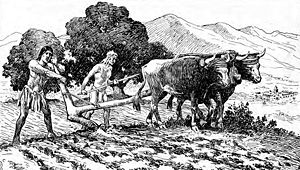

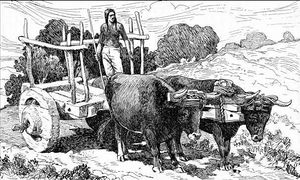

Natives utilize a primitive plow to prepare a field for planting near Mission San Diego de Alcalá.

A typical ox-drawn carreta (cart), a standard form of conveyance in the early days.

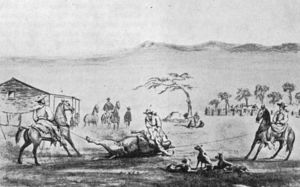

"The California Method" of killing cattle on the ranch, before 1875. Two cowboys on horseback have roped the steer by its hind legs and horns, respectively and have stretched it immobile so that the third cowboy, at center, is able to safely slit the throat of the bull with the knife he holds.

A view of the Catalan forges at Mission San Juan Capistrano (built circa 1790), the oldest existing facilities of their kind in the State of California. The sign at the lower right-hand corner proclaims the site as being "...part of Orange County's first industrial complex."

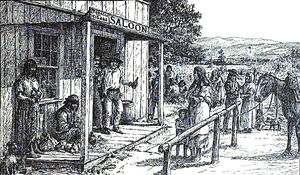

The goal of the missions was, above all, to become self-sufficient in relatively short order. Farming, therefore, was the most important industry of any mission. Barley, maize, and wheat were among the most common crops grown. Cereal grains were dried and ground by stone into flour. Even today, California is well-known for the abundance and many varieties of fruit trees that are cultivated throughout the state. The only fruits indigenous to the region, however, consisted of wild berries or grew on small bushes. Spanish missionaries brought fruit seeds over from Europe, many of which had been introduced to the Old World from Asia following earlier expeditions to the continent; orange, grape, apple, peach, pear, and fig seeds were among the most prolific of the imports. Grapes were also grown and fermented into wine for sacramental use and again, for trading. The specific variety, called the Criolla or "Mission grape," was first planted at Mission San Juan Capistrano in 1779; in 1783, the first wine produced in Alta California emerged from the mission's winery. Mission San Gabriel Arcángel would unknowingly witness the origin of the California citrus industry with the planting of the region’s first significant orchard in 1804, though the commercial potential of citrus would not be realized until 1841.[150] Olives (first cultivated at Mission San Diego de Alcalá) were grown, cured, and pressed under large stone wheels to extract their oil, both for use at the mission and to trade for other goods. Father Serra set aside a portion of the Mission Carmel gardens in 1774 for tobacco plants, a practice which soon spread throughout the mission system.[151]

It was also the missions' responsibility to provide the Spanish forts, or presidios, with the necessary foodstuffs, and manufactured goods to sustain operations. It was a constant point of contention between missionaries and the soldiers as to how many fanegas [152] of barley, or how many shirts or blankets the mission had to provide the garrisons on any given year. At times these requirements were hard to meet, especially during years of drought, or when the much anticipated shipments from the port of San Blas failed to arrive. The Spaniards kept meticulous records of mission activities, and each year reports submitted to the Father-Presidente summarizing both the material and spiritual status at each of the settlements.

Livestock was raised, not only for the purpose of obtaining meat, but also for wool, leather, and tallow, and for cultivating the land. In 1832, at the height of their prosperity, the missions collectively owned:

- 151,180 head of cattle;

- 137,969 sheep;

- 14,522 horses;

- 1,575 mules or burros;

- 1,711 goats; and

- 1,164 swine.[153]

All of these animals were originally brought up from Mexico. A great many Indians were required to guard the herds and flocks, which created the need for "...a class of horsemen scarcely surpassed anywhere." [54] These animals multiplied beyond the settler's expectations, often overrunning pastures and extending well-beyond the domains of the missions. The giant herds or horses and cows took well to the climate and the extensive pastures of the Coastal California region, but at a heavy price for the Native inhabitants. The uncontrolled spread of these new species quickly exhausted the grasslands and hillsides the Indians depended on for their seed harvests. This problem was also recognized by the Spaniards themselves, who at times sent out extermination parties to kill thousands of excess livestock, when the populations grew beyond their control. Mission kitchens and bakeries prepared and served thousands of meals each day. Candles, soap, grease, and ointments were all made from tallow (rendered animal fat) in large vats located just outside the west wing. Also situated in this general area were vats for dyeing wool and tanning leather, and primitive looms for weavings. Large bodegas (warehouses) provided long-term storage for preserved foodstuffs and other treated materials. Settlements had to fabricate virtually all needed construction materials from local resources. Workers in the carpintería (carpentry shop) used crude methods to shape beams, lintels, and other structural elements; more skilled artisans carved doors, furniture, and wooden implements. For certain applications bricks (ladrillos) were fired in ovens (kilns) to strengthen them and make them more resistant to the elements; when tejas (roof tiles) eventually replaced the conventional jacal roofing (densely-packed reeds) they were placed in the kilns to harden them as well. Glazed ceramic pots, dishes, and canisters were also made in mission kilns.

Prior to the establishment of the missions, the native peoples relied on their tribal knowledge in the use of a wide array of local materials including bone, seashells, stone, and wood, as well as handed-down techniques in tool and weapon making.[154] The missionaries' viewpoint, however, was that the Indians, who lacked experience in the Old World crafts, had to be taught industry in order to learn how to be self-sufficient (even though the natives had supported themselves for millennia). The result was the establishment of a great manual training school that comprised agriculture, the mechanical arts, and the raising and care of livestock. In time, a majority of the materials consumed and otherwise utilized by the natives was produced at the missions under the supervision of the padres; thus, the neophytes not only supported themselves in their new settings, but after 1811 sustained the entire military and civil government of California.[155] The foundry at Mission San Juan Capistrano was the first to introduce the Indians to the Iron Age. The blacksmith used the mission’s Catalan furnaces (California’s first) to smelt and fashion iron into everything from basic tools and hardware (such as nails) to crosses, gates, hinges, even cannon for mission defense. Iron was one commodity in particular that the mission relied solely on trade to acquire, as the missionaries had neither the know-how nor the technology to mine and process metal ores.

No study of the missions would be complete without mention of their extensive water supply systems. Stone zanjas (aqueducts), sometimes spanning miles, brought fresh water from a nearby river or spring to the mission site. Baked clay pipes, joined together with lime mortar or bitumen, deposited the water into large cisterns and gravity-fed fountains, and emptied into waterways where the force of the water was used to turn grinding wheels and other simple machinery, or dispensed for use in cleaning. Water used for drinking and cooking was allowed to trickle through alternate layers of sand and charcoal to remove the impurities.

Legacy[edit]

"Causes of Indian ruin: The White Man's greed; the White Man's vices and diseases; the White Man's whiskey." [156]

A view of Mission San Juan Capistrano in April of 2005. The Mission has earned a reputation as the "Loveliest of the Franciscan Ruins." [157]

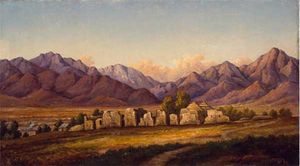

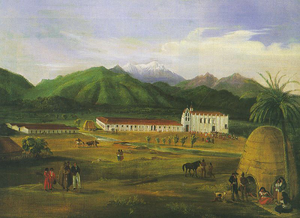

Mission San Gabriel Arcángel in 1832. The work is believed to be the earliest known oil landscape of Southern California.

The bell of El Camino Real at La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los Angeles, also known as the Los Angeles Plaza Church ("La Placita").

The San Gabriel Mission Playhouse (built in 1927), modeled after the Mission San Antonio de Padua in Monterey County.

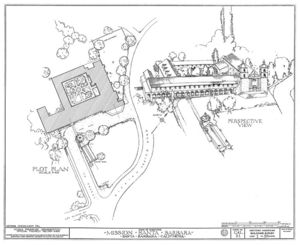

A plot plan and perspective view of Mission Santa Barbara as prepared by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1937.

Many, though not all, modern anthropologists cite a cultural bias on the part of the missionaries that blinded them to the natives' plight and caused them to develop strong negative opinions of the California Indians.[158][159] Recent scholarly interest in the subject has helped to overcomes these prejudices, though centuries of forced acculturation and the lack of written sources predating European conquest make it highly unlikely that a complete understanding of the primordial religious practices will ever be possible.[160] Fray Gerónimo Boscana, a Franciscan scholar who was stationed at Mission San Juan Capistrano for more than a decade beginning in 1812, compiled what is widely considered to be the most comprehensive study of prehistoric religious practices in the San Juan Capistrano valley.[161] The appellation "Mission Indians" was coined in 1906 as regarded California's native American population by Alfred L. Kroeber and Constance Du Bois, as an ethnographic and anthropological label collectively intended to refer to those groups that wee attached to the missions beginning at San Diego and extending up to San Luis Obispo.[162] The modern usage of the term generally applies to all tribal groups that resided within the mission system's sphere of influence. The California Gold Rush and subsequent American settlement had even more devastating effects on the native populations than did Spanish colonization, homicide being the greatest factor in their reduction.[163] It should be noted that these attrition rates are not unique to the Pacific Coastal region; virtually every area subjected to European colonization worldwide suffered similar deleterious effects.[164]

From an architectural and cultural standpoint, no other group of structures in the United States elicits the intense interest inspired by the missions of California (California is home to the greatest number of well-preserved missions found in any U.S. state).[165] The missions are collectively the best-known historic element of the coastal regions of California:

- All but two of the missions proper are owned and operated by the Catholic Church, as well as the Mission San Antonio de Pala, which was originally established as the San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (Mission La Purísima Concepción and Mission San Francisco Solano are administered by the California Department of Parks and Recreation as State Historic Parks);

- Nine mission sites are designated as National Historic Landmarks, sixteen are listed in the National Register of Historic Places (plus the related Las Flores Estancia), and all are designated as California Historical Landmarks for their historic, architectural, and archaeological significance;

- Four of the missions still run under the auspices of the Franciscan Order (San Antonio de Padua, Santa Barbara, San Miguel Arcángel, and San Luis Rey de Francia); and

- Four of the missions (San Diego de Alcalá, San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo, San Francisco de Asís, and San Juan Capistrano) have been designated minor basilicas by the Holy See due to their cultural, historic, architectural, and religious importance.

Because virtually all of the artwork at the missions served either a devotional or didactic purpose, there was no underlying reason for the mission residents to record their surroundings graphically; visitors, however, found them to be objects of curiosity.[166] During the 1850s a number of artists found gainful employment as draftsmen attached to expeditions sent to map the Pacific coastline and the border between California and Mexico (as well as plot practical railroad routes); many of the drawings were reproduced as lithographs in the expedition reports. In 1875 American illustrator Henry Chapman Ford began visiting each of the twenty-one mission sites, where he created a historically-important portfolio of watercolors, oils, and etchings. His depictions of the missions were (in part) responsible for the revival of interest in the state's Spanish heritage, and indirectly for the restoration of the missions. The 1880s saw the appearance of a number of articles on the missions in national publications and the first books on the subject; as a result, a large number of artists did one or more mission paintings, though few attempted series.[166][167] The continued popularity of the missions also stems largely from Helen Hunt Jackson's 1884 novel Ramona and the subsequent efforts of Charles Fletcher Lummis, William Randolph Hearst, and other members of the "Landmarks Club of Southern California" to restore four of the missions in the early 20th century (those being San Juan Capistrano, San Diego, San Fernando, and Pala).[168] Lummis wrote in 1895,

In ten years from now—unless our intelligence shall awaken at once—there will remain of these noble piles nothing but a few indeterminable heaps of adobe. We shall deserve and shall have the contempt of all thoughtful people if we suffer our noble missions to fall. [169]

In acknowledgement of the magnitude of the restoration efforts required and the urgent need to have acted quickly to prevent further or even total degradation, Lummis went on to state,

It is no exaggeration to say that human power could not have restored these four missions had there been a five year delay in the attempt.[170]

In 1911 author John Steven McGroarty penned The Mission Play, a three-hour pageant describing the California missions from their founding in 1769 through secularization in 1834, and ending with their "final ruin" in 1847. In the early 1930s, teams from the Historic American Buildings Survey {HABS} visited sixteen mission sites (as well as the San Antonio de Pala Asistencia and Los Angeles Plaza Church) and conducted "multi-format surveys" comprised of the preparation of measured drawings, the taking of large-format photographs, and the collection of historic documents.[171] Today, the missions exist in varying degrees of architectural integrity and structural soundness. In some cases (at San Rafael, Santa Cruz, and Soledad, for example), the current buildings are replicas constructed on or near the original site. Other mission compounds remain relatively intact and true to their original, Mission Era construction. A notable example of an intact complex is the Mission San Miguel Arcángel: its chapel retains the original interior murals created by Salinan Indians under the direction of Esteban Munras, a Spanish artist and the last Spanish diplomat to California. Many missions have preserved (or in some cases reconstructed) historic features in addition to chapel buildings. The missions have earned a prominent place in California's historic consciousness, and a steady stream of tourists from all over the world visit them. The "California 4th Grade Mission Project" requires fourth-grade students in enrolled California public schools to (at minimum) conduct research into, and prepare a report on, the missions.

On November 30, 2004 President George W. Bush signed into law H.R. 1446, the "California Missions Preservation Act," a measure which would have provided (on a one-to-one matching basis) up to $10 million in funding to the California Missions Foundation over over a five-fiscal-year period for projects related to the physical preservation of the missions, including structural rehabilitation, stabilization, and conservation of mission art and artifacts.[172] However, Americans United for Separation of Church and State (a Washington D.C.-based lobbying group) immediately thereafter filed a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the Act, which (though the case never went to trial) effectively blocked issuance of the funding.[173] In 2006, an amendment to the California Constitution was sought by California State Senator Abel Maldonado that would have allowed the use of State funds in restoration efforts under California's Proposition 40, and endowment fund that goes to the preservation and restoration of state historical and cultural resources (the Constitution prohibits giving public aid to "support or sustain a sectarian institution"). The proposed measure failed to garner the required two-thirds votes in both houses needed to place the issue on the State's ballot.[174] Today, the missions attract millions of visitors each year, and rank among the top tourist destinations in the state.[175]

Folklore[edit]

The largest California pepper tree (Schinus molle) in the United States once graced the grounds of Mission San Juan Capistrano (until 2005, when it was felled due to illness).[176] The 57-foot (17-meter) tall specimen, planted in the 1870s, was typical of the early California landscape; it was also listed in the National Register of Big Trees. The oldest pepper tree in California resides in the courtyard of Mission San Luis Rey de Francia.[177]

See also[edit]

- Mission Buenaventura-class oiler, a series of twenty-seven T2 tankers built during World War II for auxiliary service in the United States Navy.

Notes and references[edit]

- ↑ (PD) Drawing: Antonio García Cubas

- ↑ Saunders and Chase, p. 65

- ↑ Rawls, p. 29: The temporary shelters were utilized primarily for sleeping or as refuge in cases of inclement weather. Europeans generally regarded such contrivances as "...evidence of the Indians' inability to fashion more sophisticated structures."

- ↑ Paddison, pp. 81-82: In the late 1780s, French naval officer and explorer Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse described the native dwellings in and around Monterey—consisting of long poles stuck in the ground and drawn together to form arches, then covered with thatch—as "...the most miserable that are to be met with among any people." British naval officer and explorer George Vancouver documented similar conditions as observed during his 1792 visit to the San Francisco Bay area in A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean.

- ↑ Paddison, p. 333: The first indisputable archaeological evidence of human presence in California dates back to circa 8,000 BCE.

- ↑ Jones and Klar 2005, pp. 369-400: Recent research suggests that the Chumash may have been visited by Polynesians between 400 and 800 CE, nearly 1,000 years before Columbus reached North America. Although the concept was generally rejected for decades and remains controversial, studies published in peer-reviewed journals have given the idea greater plausibility.

- ↑ Jones and Klar 2007, p. 53: "Understanding how and when humans first settled California is intimately linked to the initial colonization of the Americas."

- ↑ Margolin, pp. 2-6

- ↑ Oakley, p. 1172

- ↑ Paddison, p. x

- ↑ The Spanish claim to the Pacific Northwest had dated back to a 1493 papal bull (Inter caetera) issued by Pope Alexander VI and rights contained in the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas; these two formal acts gave Spain the exclusive rights to colonize all of the Western Hemisphere (save for Brazil), including the west coast of North America.

- ↑ The term "Alta California" as applies to the mission chain founded by Serra refers specifically to the modern-day U.S. State of California.

- ↑ Paddison, p. xii: Despite Vizcaíno's recommendations, the Spanish government felt that Alta California was too distant to effectively colonize, and at the same time too close to Mexico to warrant the establishment of a port at San Diego; a royal order prohibiting further exploration of the region was issued in 1606.

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 10: Father Antonio de la Ascensión, a Carmelite priest who visited San Diego with Vizcaíno's 1602 expedition, "surveyed the area and concluded that the land was fertile, the fish plentiful, and gold abundant." Ascensión was convinced that California's potential wealth and strategic location merited colonization, and in 1620 recommended in a letter to Madrid that missions be established in the region, a venture that would involve military as well as religious personnel.

- ↑ Morrison, p. 214: During his voyage of exploration along the Pacific Coast of North America in 1579, Sir Francis Drake claimed the region (which he dubbed Nova Albion, Latin for "New Britain") in the name of England, a full generation before the first landing in Jamestown, Virginia. In order to preserve an uneasy peace with Spain, and to avoid having Spain threaten England's claims in the New World, both the discovery of and claim on New Albion was ordered by Queen Elizabeth I to be treated as a state secret.

- ↑ Chapman, p. 216: "It is usually stated that the Spanish court at Madrid received reports about Russian aggressions in the Pacific northwest, and sent orders to meet them by the occupation of Alta California, wherefore the expeditions of 1769 were made. This view contains only a smattering of the truth. It is evident from [José de] Gálvez's correspondence of 1768 that he and [Carlos Francisco de] Croix had discussed the advisability of an immediate expedition to Monterey, long before any word came from Spain about the Russian activities."

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, pp. 11-12: California had been visited a number of times since Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo’s discovery in 1542, which initially included notable expeditions led by Englishmen Francis Drake in 1579 and Thomas Cavendish 1587, and later on by Woodes Rogers (1710), George Shelvocke (1719), James Cook (1778), and finally George Vancouver in 1792. Spanish explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno made landfall in San Diego Bay in 1602, and the famed conquistador Hernán Cortés explored the California Gulf Coast in 1735.

- ↑ Rawls, p. 3

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 10: "Other pioneers have blazed the way for civilization by the torch and the bullet, and the red man has disappeared before them; but it remained for the Spanish priests to undertake to preserve the Indian and seek to make his existence compatible with a higher civilization."

- ↑ "Old Mission Santa Inés:" Per clerical historian Maynard Geiger, "This was to be a cooperative effort, imperial in origin, protective in purpose, but primarily spiritual in execution."

- ↑ Rawls, p. 6

- ↑ Kroeber 1925, p. vi.: "In the matter of population, too, the effect of Caucasian contact cannot be wholly slighted, since all statistics date from a late period. The disintegration of native numbers and native culture have proceeded hand in hand, but in very different rations according to locality. The determination of population strength before the arrival of whites is, on the other hand, of considerable significance toward the understanding of Indian culture, on account of the close relations which are manifest between type of culture and density of population."

- ↑ Chapman, p. 383: "...there may have been about 133,000 [native inhabitants] in what is now the state as a whole, and 70,000 in or near the conquered area. The missions included only the Indians of given localities, though it is true that they were situated on the best lands and in the most populous centers. Even in the vicinity of the missions, there were some unconverted groups, however."

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 15: Due to the isolation of the Baja California missions, the decree for expulsion did not arrive in June of 1767, as it did in the rest of New Spain, but was delayed until the new governor, Portolà, arrived with the news on November 30. Jesuits from the operating missions gathered in Loreto, whereupon they left for exile on February 3, 1768.

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 16

- ↑ James, p. 11

- ↑ Guest: "The blueprint for Alta California provided for a system of settlements significantly different from those in Baja California and Sonora. In their original design, both presidios and missions were different from their predecessors to the south. The plan to make the presidios agriculturally productive did not succeed. Neither did the plan for the mission-pueblos as racially integrated nuclei of urban centers, but the ideal of a closer association between "missionized" Indians and gente de razón, notwithstanding the opposition of the friars, was partially realized. The Spanish government, in its approach to the problem of colonizing Alta California, did not blindly tread the beaten track of past practices and traditions. Willing to correct the mistakes of the past, prepared to experiment with new ideas, ready to change, to modify, to adjust, the civil and military authorities of New Spain and of Alta California were open-minded, flexible, resourceful, and inventive."

- ↑ Capron, p. 3

- ↑ Loreto (or Conchó) was the first Spanish settlement in Baja California Sur, and served as the capital of Las Californias from 1697 to 1777.

- ↑ James, p. 20: A third vessel, the San José, stood out from Loreto on June 16 in relief of the San Carlos but failed to make landfall in San Diego; the ship disappeared during her subsequent voyage from the coastal town of San Blas and was assumed to be lost with all hands.

- ↑ James, pp. 18-20; Serra founded the Mission San Fernando Rey de España de Velicatá the day prior to his departure, on May 14.

- ↑ James, pp. 20-21

- ↑ Yenne, p. 24

- ↑ Bancroft, pp. 33-34

- ↑ Hittell, p. 499: "By that time, it was found that the Russians were not such undesirable neighbors as in 1817 it was thought they might become...the Russian scare, for the time being at least was over; and as for the old enthusiasm for new spiritual conquests, there was none left."

- ↑ Young, p. 17

- ↑ Robinson, p. 25

- ↑ Newcomb, p. 15

- ↑ Harley

- ↑ Ruscin, p. 61

- ↑ Chapman, p. 418: Chapman does not consider the sub-missions (asistencias) that make up the inland chain in this regard.

- ↑ Guest: "Almost from its beginning the pattern of settlement and missions in Alta California symbolized the growing tension between the traditional model of mission colonization in America and the reforming Spanish authorities of the late 18th century. The Laws of the Indies regulated the distances between pueblos of Spaniards and reducciones of Indians. In the case of Mission Santa Clara and Pueblo San Jose, and of Mission Santa Cruz and the Villa de Branciforte, these laws were clearly violated...In both cases a stream of water separated mission and town but this was a circumstance which did little either to alter or even weaken the terms of the law. In each case the close proximity between mission and town was forbidden by still further clauses of the Laws of the Indies."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, pp. 350-351. One such hypothesis was put forth by author by Prent Duel in his 1919 work Mission Architecture as Exemplified in San Xavier Del Bac: "Most missions of early date possessed secret passages as a means of escape in case they were besieged. It is difficult to locate any of them now as they are well concealed."

- ↑ Kelsey, p. 18

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 258

- ↑ Engelhart 1920, p. 75: Missionary Father Pedro Font later described the scene: "...Rivera entered the chapel with drawn sword...con la espada desnuda en la mano."

- ↑ Engelhardt 1920, p. 76: Rivera y Moncada was subsequently excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church for his actions.

- ↑ Yenne, p. 10

- ↑ Ives, p. 21: "The route followed by the Serra expeditions (plural) from Loreto to San Diego has been the subject of much study, much field work, and much argument...Even among professional historians, the magnitude of the Serra and related journeys is seldom realized. The first part, from Loreto to San Diego, equals a trip...from New York City to Lansing, Michigan. The journey of the military party, which led to the discovery of San Francisco Bay, equaled a trip...from New York City to Fort Dodge, Iowa."

- ↑ Engstrand

- ↑ Leffingwell, p. 25

- ↑ Engelhardt 1922, p. 258: Today, the site (located at 33°25′41.58″N, 117°36′34.92″W on Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in San Diego County) is referred to more commonly as La Cañada de los Bautismos, literally "The Gorge of the Baptisms," or simply Los Christianitos, "The Little Christians" and is designated as California Historical Landmark #562.

- ↑ Robinson, p. 28

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Engelhardt 1908, pp. 3-18

- ↑ Bennett 1897a, p. 13

- ↑ Ives, p. 21: "...the support of the California Missions required perhaps ten million mule-miles of travel...from Loreto to San Diego."