Species (biology)

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

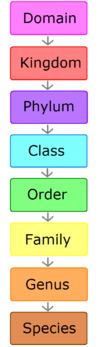

The species is the basic taxonomic unit in the biological classification. All definitions of species include some criteria on how to delineate groups of individuals such that they form a single group of interbreeding individuals. Beyond that, no consensus exists.

The most commonly used definition is Ernst Mayr’s Biological Species Concept: A species is a group of interbreeding individuals that do not interbreed with other such groups. A major problem with this concept is that it is often hard to determine whether one group of interbreeding individuals actually cannot interbreed with another group of interbreeding individuals. As a result, other species concepts that are often more practical have been proposed, each with their own drawbacks. Examples of such concepts include the Morphological, Ecological and Phylogenetical species concepts.

Even though such difficulties exist, species, and the concept of what constitutes a species, are indispensable in biology, as it provides the basis for all communication about the organisms that surround us.[1] For example: The biological discipline of taxonomy, which classifies organisms into species, requires a species concept. In defining the species concept, biologists concomitantly shed light on the mechanisms leading to speciation, contributing to their research program. Ecological studies of the interactions among species, and species relations with the abiotic world, require a species concept in order to rationally delimit species. Issues relating to conservation, agriculture, and medicine depend on a species concept to delimit species, for environmental, sociological, and legislative purposes.

Some general problems surrounding the concept of species will be discussed, and then a number of important species concepts will treated individually.

Problems with species concepts[edit]

The controversy over which concept to apply is primarily practical, namely that the variation within a species and amongst closely related species is so big that it is difficult, if not impossible for us to properly assign species boundaries to all apparent forms. There is however also a deeper philosophical problem in the way people, and more specifically systematic biologists, perceive the world around us[2]. Organisms clearly are real biological entities, but are species? Or are they perhaps only our abstract interpretation of the biodiversity that surrounds us?[3] Most discussion on species concepts has focused on well know groups such as plants and animals, but what about prokaryotes with problems like horizontal gene transfer and also the sheer difficulty of observation of such miniature organisms?[4] Perhaps the truest definition of a species is that it is a group of organisms that constitute a keyable unit, as some British taxonomists say. This is a definition that points directly at the original purpose of the concept of species, namely an unambiguous name under which one can file all the information about an organism, the key being a description, or possibly a DNA-sequence, for each single group we deem to be a species.

Morphological species concept[edit]

The morphological species concept is the most intuitive of the possible concepts and is also the oldest. It stems basically from the idea that species are groups which are constant in appearance, which, when we first look around in nature, seems quite plausible. The morphological differences between each species allow us to distinguish them from each other, a lion from a tiger, an oak from a daisy etc. Carolus Linnaeus used this concept to catalogue the diversity of life in his ‘Systema Naturae’, and gave us the binomial name with which we still attempt to classify all the organisms that live around us. The concept is however firmly grounded in the idea that species do not change, and ever since Charles Darwin published ‘The Origin of Species’ in 1859, the major consensus (at least in academia) is that species are in fact changing quite a lot[5]. As we can read in a paper by Ernst Mayr, Darwin made little distinction between species and varieties, as could be expected from a man who had argued that each variety slowly accumulated the variation that finally made it so distinct from other varieties to call it a species [6]. The immediate implication of Darwin’s work is of course that the morphological species concept is quite inadequate when it comes to understanding how species are formed, though it is often still applied to describe newly discovered species.

Biological species concept[edit]

It was Ernst Mayr, one of the founding fathers of the modern synthesis in evolutionary theory, who first developed a species concept that did explain what a species was in evolutionary terms. A species, in his vision, is more than just a human representation of all forms of life. He stated that species are: ”groups of actually or potentially interbreeding populations, which are reproductively isolated from other such groups”[5]. This view on species strongly focuses on gene flow between populations, and species are said to be reproductively isolated.

Reproductive isolation can be acquired by a species in number of way grouped in socalled pre- and post zygotic barriers. Prezygotic barriers include factors such as the physical inability to mate with another species. Postzygotic barriers include for instance genomic incompatibility leading to inviable offspring.

Some major problems associated with this species concept are [5];

- The concept is impractical, because data on the ability to interbreed between populations is often lacking,

- The concept hardly allows the definition of species that mainly reproduce clonally, applied to the extreme it would mean that every single clonally reproducing individual would constitute a species.

- hybridism (in itself a difficult concept as some define a cross between varieties a hybrid, while others would go so far as to say that only crosses between individuals from different genera can give rise to hybrids), strictly if parents from two different species give rise to a fertile, backcrossing, individual both parent species should be counted as a single species, even though hybrids often only form in a small geographical range and its parents are morphologically distinct.

References[edit]

- ↑ Hausdorf B. (2011) Progress Toward a General Species Concept. Evolution 65(4):923-931.

- ↑ Donoghue, M.J. 1985. Critique of the Biological Species Concept and Recommendations for a Phylogenetic Alternative. The Bryologist; vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 172-181 [1]

- ↑ Note: In another way to pose this question, does our neurological wiring lead us to partition a continuum of organisms into clusters? If so, humans can lay no claim to exclusivity of such wiring since all sexually reproducing organisms recognize clusters, in that male eagles do not look for female hawks to mate with, nor do male lions look for female panthers, or female gorillas look for male chimpanzees. (See: Coyne JA. (2009) "The Origin of Species". In: Why Evolution Is True. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0670020539.)

- ↑ Rossellö-Mora, R., Amann, R. 2001. The species concept for prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiology Reviews; vol. 25, pp. 39-67 [2]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sokal, R.R., Crovello, T.J. 1970. The Biological Species Concept: A Critical Evaluation. The American Naturalist; vol. 104, no. 936, pp. 127-153 [3]

- ↑ Mayr, E. 1949. Speciation and Selection. Proc. Am. Phil. Soc.; vol. 93, no. 6, pp 514-519 online edition

KSF

KSF