The Lord of the Rings

From Citizendium - Reading time: 27 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 27 min

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

The Lord of the Rings is an epic high fantasy novel written by the English author and philologist J. R. R. Tolkien. The story began as a sequel to Tolkien's earlier work, The Hobbit, but developed into a much larger story. It was originally published in three volumes (The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers and The Return of the King) in 1954 and 1955, and it is in this three-volume form that it is popularly known. Fans who discovered it during the 1960s called it "the trilogy", although it is actually one continuous story.

The Lord of the Rings is set in an imaginary land called Middle Earth. It is populated with Men, as well as various fictitious creatures such as Hobbits, Elves, Dwarves and Orcs and centers around a Ring of Power created by Sauron, the Dark Lord. It involves a large number of characters, peoples and places encountered on a journey that a company of the "free" or "good" people undertake in an attempt to destroy the Ring and defeat Sauron. The main narrative is succeeded by half-a-dozen appendices which offer historical and linguistic background material.

Although a major work in itself, the story is only the last part of a mythology that Tolkien had worked on since 1917.[1] The Lord of the Rings is considered to have had a great effect on modern fantasy, and the impact of Tolkien's works is such that the use of the words "Tolkienian" and "Tolkienesque" has been recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary.[2] Its immense and enduring popularity has led to numerous references in popular culture, the founding of many societies by fans of Tolkien's works,[3] and the publication of many books about Tolkien and his works. The Lord of the Rings has inspired, and continues to inspire, artwork, music, films and television, video games and subsequent literature. Adaptations of The Lord of the Rings have been made for radio, theatre, and film. The 2001–03 release of the widely acclaimed Lord of the Rings film trilogy prompted a new surge of interest in The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien's other works.[4]

Background[edit]

The historical background of the story of The Lord of the Rings is revealed as the book progresses, and is also elaborated upon in the Appendices and in The Silmarillion, the latter published after Tolkien's death. It begins thousands of years before the action in the book with the eponymous Lord of the Rings, the Dark Lord Sauron, who secretly forged a Great Ring of power, the One Ring, to enslave the wearers of the other Rings of Power. He launched a war during which he captured 16 of the Rings of Power and distributed these to seven and nine lords of Dwarves and Men respectively; the Men who possessed the Nine were corrupted over time and became the undead Nazgûl or Ringwraiths, Sauron's most feared servants. Sauron failed to capture the remaining Three, which remained in the possession of the Elves. The Men of the great island-nation of Númenor helped the besieged Elves in the war, and much later they sent a great force to overthrow Sauron, who surrendered, and was taken to Númenor as a prisoner. However, with cunning Sauron poisoned the minds of the Númenóreans against the Valar (deities in Tolkien's mythology) and deceived them into invading the Undying Lands, for which act Númenor was destroyed. Sauron's spirit escaped to Middle-earth, as did some Númenóreans who had opposed the invasion, led by Elendil and his sons Isildur and Anárion.

Over 100 years later, Sauron was at war with the Númenórean exiles who had established themselves in Middle-earth. Elendil formed the Last Alliance of Elves and Men with the Elven-king Gil-galad, and they marched against Mordor, defeating Sauron's armies and besieging his stronghold Barad-dûr; Anárion was killed during the siege. After seven years besieged, Sauron himself came forth and engaged in single combat with the leaders of the Last Alliance. Gil-galad and Elendil were both killed as they fought with Sauron, but Sauron's body was also overcome and slain.[5] Isildur cut the One Ring from Sauron's hand with Elendil's broken sword Narsil, and when this happened Sauron's spirit fled into the wilderness. Isildur was advised to destroy the One Ring outright by casting it into the volcanic Mount Doom where it was forged but, attracted to its beauty, he refused and kept it as weregild (compensation) for the deaths of his father and brother.

So began the Third Age of Middle-earth. Two years later, Isildur and his soldiers were ambushed by a band of Orcs at the Gladden Fields. Isildur escaped by putting on the Ring — which made mortal wearers invisible — but the Ring betrayed him and slipped from his finger while he was swimming in the Great River Anduin. He was seen and shot dead by Orcs, and the Ring was lost for two millennia on the river's bottom.

It was then found by chance by a river hobbit named Déagol. His relative and friend[5] Sméagol killed him for the Ring and was banished from his home. Sméagol fled into the Misty Mountains where, corrupted by the power of the Ring, he became a loathsome, slimy creature called Gollum. Much later, as told in The Hobbit, another hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, seemingly accidentally found the Ring in Gollum's cave, and took it back to his home, Bag End, unaware that it was anything more than just a magic ring.

Synopsis[edit]

The three volumes of The Lord of the Rings are each divided into two 'books', making six books in total. Book I in The Fellowship of the Ring begins in the Shire with Bilbo's 111th birthday party, about 60 years after the end of The Hobbit, set in the backdrop of Sauron's plans of war and domination.. Bilbo, departing to journey once more, left the ring to his cousin and adoptive heir, Frodo Baggins. After 17 years of investigating, their old friend, the Wizard Gandalf confirmed that this ring was in fact the One Ring, the instrument of Sauron's power, for which the Dark Lord had been searching for most of the Third Age, and which corrupted others with desire for it and the power it held. But by then Sauron also knew its whereabouts (through the capture and subsequent torture of Gollum).

Sauron sent the nine Ringwraiths, in the guise of black riders, to the Shire in search of the Ring. Frodo escaped, and with his loyal gardener Samwise "Sam" Gamgee and two close friends, Meriadoc "Merry" Brandybuck and Peregrin "Pippin" Took, set off to take the Ring to the Elven haven of Rivendell. They were aided by the enigmatic Tom Bombadil, and by a man called "Strider", who was later revealed to be Aragorn, the heir to the kingships of Gondor and Arnor, two great realms founded by the Númenórean exiles. Aragorn led the hobbits to Rivendell on Gandalf's request. Frodo was gravely wounded by the Ringwraiths at the hill of Weathertop, but, with the help of the Elf-lord Glorfindel, they managed to reach Rivendell. Book I ends with Frodo losing consciousness.

Book II reveals that Frodo managed to recover under the care of the Half-elven lord Elrond, master of Rivendell. Frodo met Bilbo, now living there in retirement, and saw Elrond's daughter Arwen, Aragorn's betrothed. Later, in a Council attended by various people of the different races of Middle-earth (Elves, Dwarves and Men) and presided over by Elrond, many past events and the current situation were made clear before all and discussed in detail, so as to take the best course possible. Gandalf told them of the emerging threat of Saruman, the leader of the Order of Wizards, who wanted the Ring for himself. The Council decided that the only course of action that could save Middle-earth was to destroy the Ring by taking it to Mordor and casting it into Mount Doom, where it had been forged. Frodo volunteered for the task, and a "Fellowship of the Ring" was formed to aid him, comprising his three Hobbit companions, Gandalf, Aragorn (who was anyway going to Gondor [which was on the way] to fight in the war against Sauron, using Anduril, the sword Narsil reforged), Boromir of Gondor, Gimli the Dwarf, and Legolas the Elf.

The company journeyed across plains and over mountains, and ultimately to the Mines of Moria, where they were tracked by Gollum, who, having been released by Sauron, desperately sought to regain the ring. When they were almost through the mines the party was attacked by Orcs. Gandalf battled a Balrog, an ancient demon creature (or spirit), and fell into a deep chasm, apparently to his death. Escaping from Moria the rest of the Fellowship, now led by Aragorn, took refuge in the Elven wood of Lothlórien, the realm of the Lady Galadriel and the Lord Celeborn. They then travelled along the great River Anduin, and Frodo decided to continue the trek to Mordor on his own, largely due to the Ring's growing influence on Boromir and the threat it posed to the others. Frodo attempted to continue his mission alone, but Sam was able to catch him at the last minute, and the two of them went off together towards Mordor.

The second volume, The Two Towers, deals with two parallel storylines, one in each of its books. The beginning of Book III tells us that the remaining members of the Fellowship were attacked by Saruman's Orcs, and in the battle Boromir was killed and Merry and Pippin kidnapped by the Orcs (Saruman, now turned traitor and seeking the One Ring himself, had sent them to capture the hobbits and bring them to him alive). Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli went off in pursuit of Merry and Pippin's captors. The three met Gandalf, who had returned. He had defeated the Balrog at the cost of his life, but had been sent back to Middle-earth because his work was not finished. The four helped Rohan defeat Saruman's armies at the Battle of the Hornburg. Meanwhile Merry and Pippin, freed from captivity by the Riders of Rohan, helped the ancient, tree-like Ents attack Saruman at his stronghold of Isengard. The two groups were reunited in the aftermath of battle. Saruman refused to repent his folly and Gandalf cast him from the Order of Wizards.

Book IV tells of Frodo and Sam's exploits on the way to Mount Doom. They managed to capture Gollum and convinced him to guide them to the Black Gate, which, on reaching, they found to be impenetrable. Gollum then suggested a secret path into Mordor, through the dreaded valley of Minas Morgul. While travelling there, the three were captured by Rangers of Gondor led by Boromir's brother Faramir, but managed to convince Faramir that the Ring was better off destroyed than used as a weapon. At the end of the volume, Gollum betrayed Frodo to the great spider Shelob, hoping to scavenge the Ring from Frodo's remains after she had consumed the hobbit. Shelob's bite paralysed Frodo, but Sam then fought her off. Frodo was taken by orcs to the nearby fortress of Cirith Ungol. Sam had thought his master dead, and saved the Ring, but was now left to find Frodo's whereabouts. Meanwhile, Sauron launched an all-out military assault upon Middle-earth, precipitating the War of the Ring, with the Witch-king (leader of the Ringwraiths) leading a large army into battle against Gondor.

The third volume, The Return of the King, begins with Gandalf arriving at Minas Tirith in Gondor with Pippin, to alert the city of the impending attack. Merry joined the army of Rohan, while the others led by Aragorn elected to journey through the 'Paths of the Dead' in the hope of enlisting the help of an undead army against the Corsairs of Umbar. Gandalf, Aragorn and the others of the Fellowship then assisted in the battles against the armies of Sauron, including the siege of Minas Tirith. With the timely aid of Rohan's cavalry and Aragorn's assault up the river, a significant portion of Sauron's army was defeated and Minas Tirith saved. However Sauron still had thousands of troops available, and the main characters were forced into a climactic all-or-nothing battle before the Black Gate of Mordor, where the alliance of Gondor and Rohan fought desperately against Sauron's armies in order to distract him from the Ringbearer, and hoped to gain time for Frodo to destroy it.

In Book VI, Sam rescued Frodo from captivity. The pair then made their way through the rugged lands of Mordor and, after much struggle, finally reached Mount Doom itself (tailed closely by Gollum). However, the temptation of the Ring proved too great for Frodo, and he claimed it for himself in the end, and so Sauron discovered his presence. While the Ringwraiths flew at top speed toward Mount Doom, Gollum struggled with Frodo for the Ring and managed to bite the Ring off Frodo's finger. Crazed with triumph, Gollum slipped into the Cracks of Doom, and the Ring was destroyed. With the end of the Ring, Sauron's armies lost heart, the Ringwraiths disintegrated, and Aragorn's army was victorious.

Thus, Sauron was banished from the world and his realm ended. Aragorn was crowned king of Gondor and married Arwen, the daughter of Elrond. All conflict was not over, however, for Saruman had managed to escape his captivity and enslave the Shire. Although he was soon overthrown by the Hobbits, and the four heroes helped to restore order and beautify the land which had been spoiled by industrialization . At the end, Frodo remained wounded in body and spirit and, accompanied by Bilbo, sailed west over the Sea to the Undying Lands, where he could find peace.

The Appendices contain much material concerning the timeline of the story, and information on the peoples and the languages of Middle-earth.

Concept and creation[edit]

Writing[edit]

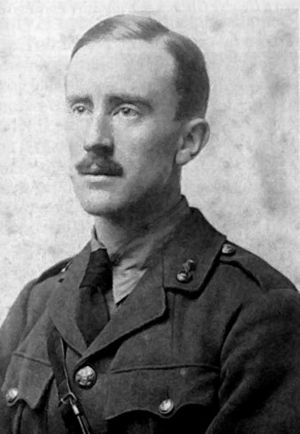

J. R. R. Tolkien

The Lord of the Rings was started as a sequel to The Hobbit, a fantasy story published in 1937 that Tolkien had originally written for and read to his children.[6] The popularity of The Hobbit led to demands from his publishers for more stories about hobbits and goblins, and so that same year, at the age of 45, Tolkien began writing the story that would become The Lord of the Rings. The story would not be finished until 12 years later, in 1949, and it would not be fully published until 1955, by which time Tolkien was 63 years old.

Tolkien did not originally intend to write a sequel to The Hobbit, and instead wrote several other children's tales, such as Roverandom. As his main work, Tolkien began to outline the history of Arda, telling tales of the Silmarils, and many other stories of how the races and situations that we read about in the Lord of the Rings came to be. Tolkien died before he could complete and put together this work, today known as The Silmarillion, but his son Christopher Tolkien edited his father's work, filled in gaps, and published it in 1977.[7]Nevertheless, the work occupied the greater part of the elder Tolkien's time. As a result The Lord of the Rings ended up as the last movement of his legendarium.

Persuaded by his publishers, he started 'a new Hobbit' in December 1937.[6] After several false starts, the story of the One Ring soon emerged. The idea of the first chapter ("A Long-Expected Party") arrived fully-formed, although the reasons behind Bilbo's disappearance, the significance of the Ring, and the title The Lord of the Rings did not arrive until the spring of 1938.[6] Originally, he planned to write a story in which Bilbo had used up all his treasure and was looking for another adventure to gain more; however, he remembered the ring and its powers and decided to write about it instead.[6] He began with Bilbo as the main character, but decided that the story was too serious to use the fun-loving hobbit. Thus Tolkien looked for an alternate character to carry the ring, and he turned to members of Bilbo's family.[6] He thought about using a son, but this generated some difficult questions, such as the whereabouts of Bilbo's wife and whether he would let his son go into danger. In Greek legend, it was a hero's nephew that gained the item of power, and so the hobbit Frodo came into existence.[6] (Technically Tolkien made Frodo Bilbo's second cousin once removed, but because of age differences the two were to consider each other nephew and uncle.)

Writing was slow due to Tolkien's perfectionism, and was frequently interrupted by his obligations as an examiner, and by other academic duties. "I have spent nearly all the vacation-times of seventeen years examining […] Writing stories in prose or verse has been stolen, often guiltily, from time already mortgaged…" His letters show that he abandoned The Lord of the Rings during most of 1943 and only re-started it in April 1944. He wrote to Christopher Tolkien (who was serving in South Africa with the Royal Air Force), reporting on progress, and narrated how he read completed chapters to C.S. Lewis and others. Christopher would be sent carbon copies of chapters as they were typed up. The letters show how the book was getting out of control: "This story takes me in charge, and I have already taken three chapters over what was meant to be one!.[8] He made another push in 1946, and showed a copy of the manuscript to his publishers in 1947.[9] The story was effectively finished the next year, but Tolkien did not finish revising earlier parts of the work until 1949.[10]

A dispute with his publishers, Allen & Unwin, led to the book being offered to Collins in 1950. He intended The Silmarillion (itself largely unrevised at this point) to be published along with The Lord of the Rings, but A&U were unwilling to do this. After his contact at Collins, Milton Waldman, expressed the belief that The Lord of the Rings itself "urgently needed cutting", he eventually demanded that they publish the book in 1952. They did not do so, and so Tolkien wrote to Allen and Unwin, saying, "I would gladly consider the publication of any part of the stuff."[11]

Following the massive success of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien considered a sequel entitled The New Shadow, in which the Gondorians turn to dark cults and consider an uprising against Aragorn's son, Eldarion. Tolkien never went very far with this sequel, as it had more to do with human nature than with epic struggles, and the few pages which were written can be found in The Peoples of Middle-earth.

Publication[edit]

For publication, due largely to post-war paper shortages, but also to keep the price down, the book was divided into three volumes: The Fellowship of the Ring (Books I and II), The Two Towers (Books III and IV), and The Return of the King (Books V and VI plus six appendices). Delays in producing appendices, maps and especially indices led to the volumes being published later than originally hoped — on 21 July 1954, on 11 November and on 20 October 1955 respectively in the United Kingdom, and slightly later in the United States. The Return of the King was especially delayed. Tolkien, moreover, did not especially like the title The Return of the King, believing it gave away too much of the storyline. He had originally suggested The War of the Ring, which was dismissed by his publishers.[12]

The books were published under a 'profit-sharing' arrangement, whereby Tolkien would not receive an advance or royalties until the books had broken even, after which he would take a large share of the profits. An index to the entire three-volume set at the end of third volume was promised in the first volume. However, this proved impractical to compile in a reasonable timescale. Later, in 1966, four indices, not compiled by Tolkien, were added to The Return of the King. Because the three-volume binding was so widely distributed, the work is often referred to as the Lord of the Rings "trilogy". In a letter to the poet W. H. Auden, Tolkien himself made use of the term "trilogy" for the work[13] though he did at other times consider this incorrect, as it was written and conceived as a single book.[14]

A 1999 British seven-volume box set followed Tolkien's original six-book division, with the Appendices from the end of The Return of the King bound as a separate volume. The individual names for the books were decided based on a combination of suggestions Tolkien had made during his lifetime and the titles of the existing volumes. From Book I to Book VI, these titles were The Ring Sets Out, The Ring Goes South, The Treason of Isengard, The Ring Goes East, The War of the Ring, and The End of the Third Age.[15]

The name of the complete work is often abbreviated to LotR, or simply 'LR' (Tolkien himself used 'L.R.'), and the three volumes as FR, or FotR (The Fellowship of the Ring), TT or TTT (The Two Towers), and RK, or RotK (The Return of the King).

Since the original printings of the 1950s and 1960s, many different editions of The Lord of the Rings have appeared. In the 1990s (partly in anticipation of the forthcoming The Lord of the Rings film trilogy) several new editions were released and in 2004 a new edition was published for the fiftieth anniversary of the book's original publication.

The novel has been translated, with various degrees of success, into dozens of other languages.[16] Tolkien, an expert in philology, examined many of these translations, and had comments on each that reflect both the translation process and his work. To aid translators, Tolkien wrote his "Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings". Because it purports to be a translation of the Red Book of Westmarch, translators have an unusual degree of freedom when translating The Lord of the Rings, and in contrast to the usual modern practice, names intended to have a particular meaning in the English version are translated to provide a similar meaning in the target language. In German, for example, the name "Baggins" becomes "Beutlin" (containing the word Beutel meaning "bag"), and "elf" becomes "Elb" (Elb does not carry the connotations of mischief that its English counterpart does, and is therefore arguably a better fit for Tolkien's creation).

Influences[edit]

The Lord of the Rings developed as a personal exploration by Tolkien of his interests in philology, religion (particularly Roman Catholicism), fairy tales, as well as Norse mythology, but it was also crucially influenced by the effects of his military service during World War I.[17] Tolkien created a complete and highly detailed fictional universe (Eä), in which The Lord of the Rings was set, and many parts of this world were, as he freely admitted, influenced by other sources.[18]

Tolkien once described The Lord of the Rings to his friend, the English Jesuit Father Robert Murray, as "a fundamentally religious and Catholic work, unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision."[5] There are many theological themes underlying the narrative including the battle of good versus evil, the triumph of humility over pride, and the activity of grace. In addition the saga includes themes which incorporate death and immortality, mercy and pity, resurrection, salvation, repentance, self-sacrifice, free will, justice, fellowship, authority and healing. In addition the Lord's Prayer "And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil" was reportedly present in Tolkien's mind as he described Frodo's struggles against the power of the One Ring.[5]

Non-Christian religious motifs also had strong influences in Tolkien's Middle-earth. His Ainur, a race of angelic beings who are responsible for conceptualising the world, includes the Valar, the pantheon of "gods" who are responsible for the maintenance of everything from skies and seas to dreams and doom, and their servants, the Maiar. The concept of the Valar echoes Greek and Norse mythologies, although the Ainur and the world itself are all creations of a monotheistic deity — Ilúvatar or Eru, "The One". As the external practice of Middle-earth religion is downplayed in The Lord of the Rings, explicit information about them is only given in the different versions of Silmarillion material. However, there remain allusions to this aspect of Tolkien's writings, including "the Great Enemy" who was Sauron's master and "Elbereth, Queen of Stars" (Morgoth and Varda respectively, two of the Valar) in the main text, the "Authorities" (referring to the Valar, literally Powers) in the Prologue, and "the One" in Appendix A. Other non-Christian mythological or folkloric elements can be seen, including other sentient non-humans (Dwarves, Elves, Hobbits and Ents), a "Green Man" (Tom Bombadil), and spirits or ghosts (Barrow-wights, Oathbreakers).

The Northern European mythologies are perhaps the best known non-Christian influences on Tolkien. His Elves and Dwarves are by and large based on Norse and related Germanic mythologies.[19] Names such as "Gandalf", "Gimli" and "Middle-earth" are directly derived from Norse mythology. The figure of Gandalf is particularly influenced by the Germanic deity Odin in his incarnation as "The Wanderer", an old man with one eye, a long white beard, a wide brimmed hat, and a staff; Tolkien states that he thinks of Gandalf as an "Odinic wanderer" in a letter of 1946.[5]

Specific literature influences from European mythologies include the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf.[20] Tolkien may have also borrowed elements from the Völsunga saga (the Old Norse basis of the later German Nibelungenlied and Richard Wagner's opera series, Der Ring des Nibelungen, also called the Ring Cycle), specifically a magical golden ring and a broken sword which is reforged. In the Völsungasaga, these items are respectively Andvarinaut and Gram, and very broadly correspond to the One Ring and Narsil/Andúril. Finnish mythology and more specifically the Finnish national epic Kalevala were also acknowledged by Tolkien as an influence on Middle-earth.[21] In a similar manner to The Lord of the Rings, the Kalevala centres around a magical item of great power, the Sampo, which bestows great fortune on its owner, but never makes its exact nature clear. Like the One Ring, the Sampo is fought over by forces of good and evil, and is ultimately lost to the world as it is destroyed towards the end of the story. In another parallel, the Kalevala's wizard character Väinämöinen also has many similarities to Gandalf in his immortal origins and wise nature, and both works end with their respective wizard departing on a ship to lands beyond the mortal world. Tolkien also based his Elvish language Quenya on Finnish.[22]

It is also clear that the Ring has broad applicability to the concept of absolute power and its effects, and that the plot hinges on the view that anyone who seeks to gain absolute worldly power will inevitably be corrupted by it. The concept of the "ring of power" itself is also present in Plato's Republic, Wagner's Ring Cycle, and in the story of Gyges' ring (a story often compared to the Book of Job).

Shakespeare's Macbeth influenced Tolkien in a number of ways. The Ent attack on Isengard was inspired by "Birnam Wood coming to Dunsinane" in the play; Tolkien felt men carrying boughs were not impressive enough, and thus he used actual tree-like creatures.[23] The phrase "crack of doom" was actually coined by Shakespeare for Macbeth, with an entirely different meaning.

On a more personal level, some locations and characters were inspired by Tolkien's childhood in Sarehole and Birmingham.[24] It has also been suggested that The Shire and its surroundings were based on the countryside around Stonyhurst College in Lancashire where Tolkien frequently stayed during the 1940s.[25] The Lord of the Rings was crucially influenced by Tolkien's experiences during World War I and his son's during World War II. The central action of the books — a climactic, age-ending war between good and evil — is the central event of many mythologies, notably the Norse, but it is also a clear reference to the well-known description of World War I, which was commonly referred to as "the war to end all wars".

After the publication of The Lord of the Rings these influences led to speculation that the One Ring was an allegory for the nuclear bomb.[26] Tolkien, however, repeatedly insisted that his works were not an allegory of any kind. He states in the foreword to The Lord of the Rings that he disliked allegories and that the story was not one,[27] and it would be irresponsible to dismiss such direct statements on these matters lightly. Tolkien had already completed most of the book, including the ending in its entirety, before the first nuclear bombs were made known to the world at Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

Nevertheless, a number of the work's themes have modern resonances. There is a strong theme of despair in the face of new mechanized warfare that Tolkien himself had experienced in the trenches of World War I. Some say there is clear evidence that one of the main subtexts of the story — the passing of a mythical "Golden Age" — was influenced not only by Arthurian legend, but also by Tolkien's contemporary anxieties about the growing encroachment of urbanisation and industrialisation into the "traditional" English lifestyle and countryside.[26] The development of a specially bred Orc army, and the destruction of the environment to aid this, also have modern resonances; and the effects of the Ring on its users evoke the modern literature of drug addiction as much as any historic quest literature.

Critical response[edit]

Tolkien's work has received mixed reviews since its inception, ranging from terrible to excellent. Recent reviews in various media have been, in a majority, highly positive. On its initial review the Sunday Telegraph felt it was "among the greatest works of imaginative fiction of the twentieth century." The Sunday Times seemed to echo these sentiments when in its review it was stated that "the English-speaking world is divided into those who have read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit and those who are going to read them." The New York Herald Tribune also seemed to have an idea of how popular the books would become, writing in its review that they were "destined to outlast our time."[28]

Not all original reviews, however, were so kind. New York Times reviewer Judith Shulevitz criticized the "pedantry" of Tolkien's literary style, saying that he "formulated a high-minded belief in the importance of his mission as a literary preservationist, which turns out to be death to literature itself."[29] Critic Richard Jenkyns, writing in The New Republic, criticized a perceived lack of psychological depth. Both the characters and the work itself are, according to Jenkyns, "anemic, and lacking in fiber."[30] Even within Tolkien's social group, The Inklings, reviews were mixed. Hugo Dyson was famously recorded as saying, during one of Tolkien's readings to the group, "Oh no! Not another f***ing elf!"[31] However, another Inkling, C.S. Lewis, had very different feelings, writing, "here are beauties which pierce like swords or burn like cold iron. Here is a book which will break your heart." Despite these reviews and its lack of paperback printing until the 1960s, The Lord of the Rings initially sold well in hardback.[32]

Several other authors in the genre, however, seemed to agree more with Dyson than Lewis. Science-fiction author David Brin criticized the book for what he perceived to be its unquestioning devotion to a traditional elitist social structure, its positive depiction of the slaughter of the opposing forces, and its backward-looking characters who believed that the so-called "Golden Age" had passed.[33] Michael Moorcock, another famous science fiction and fantasy author, is also critical of The Lord of the Rings. In his essay, "Epic Pooh," he equates Tolkien's work to Winnie-the-Pooh and criticises it and similar works for their perceived Merry England point of view.[34] Incidentally, Moorcock met both Tolkien and Lewis in his teens and claims to have liked them personally, even though he does not admire them on artistic grounds.

In 1957, it was awarded the International Fantasy Award. Despite its numerous detractors, the publication of the Ace Books and Ballantine paperbacks helped The Lord of the Rings become immensely popular in the 1960s. The book has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the twentieth century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.[35] In the 2003 "Big Read" survey conducted by the BBC, The Lord of the Rings was found to be the "Nation's best-loved book." In similar 2004 polls both Germany[36] and Australia[37] also found The Lord of the Rings to be their favourite book. In a 1999 poll of Amazon.com customers, The Lord of the Rings was judged to be their favourite "book of the millennium."[38]

Some recent analysis has focused on criticisms within The Lord of the Rings held by minority groups.[39] One criticism holds that the book displays racism in its portrayal of white-skinned Men, Elves, Dwarves, and Hobbits as protagonists and dark-skinned Orcs and Men as antagonists. The book also mentions that the Númenóreans became weak when they mingled with 'lesser Men'. Critics have held that this amounts to a declaration that foreigners destroy culture, especially those of another ethnicity.[40] Among other counter-criticisms,[41] is skin colour being somewhat diverse among the Free Peoples - for example, some Hobbits were brown-skinned, and dark-skinned men help defend Minas Tirith. Tolkien also elicits sympathy for the Men serving Sauron; seeing a corpse of one such Man, Sam Gamgee contemplates whether he was "really evil of heart", or rather enslaved and deceived. The decline of the Númenóreans is also stated to be due to many factors, such as their own pride and lust for power. This racist interpretation is also seen as inconsistent with Tolkien's ideologies. In private letters, Tolkien called Nazi "race-doctrine" and antisemitism "wholly pernicious and unscientific", and apartheid. He also denounced the latter in his valedictory address to the University of Oxford in 1959.[42]

Adaptations[edit]

The Lord of the Rings has been adapted for film, radio and stage multiple times.

The book has been adapted for radio four times. In 1955 and 1956, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) broadcast The Lord of the Rings, a 12-part radio adaptation of the story. In the 1960s radio station WBAI in New York produced a short radio adaptation. A 1979 dramatization of The Lord of the Rings was broadcast in the United States and subsequently issued on tape and CD. In 1981, the BBC broadcast The Lord of the Rings, a new dramatization in 26 half-hour instalments.

Three film adaptations have been made. The first was J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (1978), by animator Ralph Bakshi, the first part of what was originally intended to be a two-part adaptation of the story (hence its original title, The Lord of the Rings Part 1). It covers The Fellowship of the Ring and part of The Two Towers. The second, The Return of the King (1980), was an animated television special by Rankin-Bass, who had produced a similar version of The Hobbit (1977). The third was director Peter Jackson's live action The Lord of the Rings film trilogy, produced by New Line Cinema and released in three instalments as The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). The final instalment of this trilogy was only the second film to break the one-billion-dollar barrier, after 1997's Titanic, and, like Titanic, won a total of 11 Oscars, including 'best film' and 'best director'. The live-action film trilogy has done much in recent years to bring the book back into the public consciousness.[4] Jackson also turned the novel The Hobbit into a trilogy of films - The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013), and There and Back Again (2014); filmed as a prequel to the live action series.

In 1990, Recorded Books published an unabridged audio version of the books. They hired British actor Rob Inglis — who had previously starred in one-man stage productions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings — to read. Inglis performs the books verbatim, using distinct voices for each character, and sings all of the songs. Tolkien had written music for some of the songs in the book; for the rest, Inglis, along with director Claudia Howard, wrote additional music.

There have been several stage productions based on the book. Full-length stage adaptations of each of The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003) were staged in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. A large-scale musical theatre adaptation, The Lord of the Rings was first staged in Toronto, Ontario, Canada in 2006 and opened in London, United Kingdom in May 2007.

Legacy[edit]

Influences on the fantasy genre[edit]

The enormous popularity of Tolkien's epic saga greatly expanded the demand for fantasy fiction. Largely thanks to The Lord of the Rings, the genre flowered throughout the 1960s. Many other books in a broadly similar vein were published, including the Earthsea books of Ursula K. Le Guin, The Riftwar Saga by Raymond Feist, The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks, the "Wheel of Time" books of Robert Jordan,[43] and, in the case of the Gormenghast books by Mervyn Peake and The Worm Ouroboros by E. R. Eddison, rediscovered. According to the Oxford Good Fiction Guide[44] the most distinguished emulators of Tolkien are Jordan, Stephen R. Donaldson and David Eddings.

With a significant overlapping of their respective followings, there has been and still is extensive cross-pollination of influence between the fantasy and science fiction genres. In this way, the work also had an influence upon such science fiction authors as Frank Herbert and Arthur C. Clarke[45] and filmmakers such as George Lucas.[46]

It strongly influenced the role playing game industry which achieved popularity in the 1970s with Dungeons & Dragons, a game which features many races found in The Lord of the Rings, most notably halflings (another term for hobbits), elves, dwarves, half-elves, orcs, and dragons. However, Gary Gygax, lead designer of the game, maintains that he was influenced very little by The Lord of the Rings, stating that he included these elements as a marketing move to draw on the popularity the work enjoyed at the time he was developing the game.[47] The video game industry has also been influenced by the legacy of The Lord of the Rings, with titles such as Ultima, Baldur's Gate, EverQuest, and the Warcraft series,[48] as well as, quite naturally, video games set in Middle-earth itself.

As in all artistic fields, a great many lesser derivatives of the more prominent works appeared. The term "Tolkienesque" is used in the genre to refer to the oft-used and abused storyline of The Lord of the Rings: a group of adventurers embarking on a quest to save a magical fantasy world from the armies of an evil dark lord, and is a testament to how much the popularity of these books has increased.

Impact on popular culture[edit]

The Lord of the Rings has had a profound and wide-ranging impact on popular culture, from its publication in the 1950s, but especially throughout the 1960s and 1970s, where young people embraced it as a countercultural saga[49] - "Frodo Lives!" and "Gandalf for President" were two phrases popular among American Tolkien fans during this time.[50] More recent examples include The Lord of the Rings-themed editions of popular board games (e.g., Risk: Lord of the Rings Trilogy Edition, chess and Monopoly);[51] and parodies such as Bored of the Rings, Lord of the Beans, the South Park episode The Return of the Fellowship of the Ring to the Two Towers, and the Mad Magazine musical send-up titled "The Ring And I". Its influence has been vastly extended in the present day, largely due to the Peter Jackson-directed live-action films.

The book, along with Tolkien's other writings, has influenced many musicians. Rock bands of the 1970s were musically and lyrically inspired by the major fantasy counter-culture of the time; British 70s rock band Led Zeppelin is arguably the most well-known group to be directly inspired by Tolkien, and have four songs that contain explicit references to The Lord of the Rings. Other 70s rock bands such as Camel, Rush and Styx were also inspired by Tolkien's work. Later, in the 80s and 90s, several (mostly Northern European) metal bands drew inspiration from Tolkien, often with a focus on the 'dark' or evil characters and forces in Tolkien's Middle-earth. These include German metal band Blind Guardian, Austrian metal band Summoning, and Finnish metal band Nightwish. Furthermore, several bands from this metal subgenre have taken their names from Tolkien's story (Burzum, Gorgoroth, Amon Amarth, Ephel Duath and Cirith Ungol for example), and even band members have adopted stage names borrowed from the story, such as Count Grishnackh and Shagrath. 1960s guitarist Steve Took also took his pseudonym in honour of the hobbit character Peregrin Took. Progressive rock bands Iluvatar and Isildur's Bane borrow their names from characters in the epic.

Outside of rock music, a number of classical and New Age music artists have also been influenced by Tolkien's work. The New Age artist Enya wrote an instrumental piece called "Lothlórien" in 1991, and composed two songs for the film The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring - "May It Be" (sung in English and Quenya) and "Aníron" (sung in Sindarin). Swedish keyboardist Bo Hansson released an instrumental album entitled "Music Inspired by Lord of the Rings" in 1970. The Danish Tolkien Ensemble have released a number of albums that have set the complete poems and songs of The Lord of the Rings to music, some featuring recitation by Christopher Lee.

References[edit]

Text[edit]

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1954 [2005]). The Lord of the Rings. Houghton Mifflin. paperback: ISBN 0-618-64015-0

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1937 [2002]). The Hobbit. Houghton Mifflin. paperback: ISBN 0-618-26030-7

- Tolkien, J.R.R. (1977 [2004]). The Silmarillion. Houghton Mifflin. paperback: ISBN 0-618-39111-8

References[edit]

- ↑ J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch. Retrieved on 2006-06-16.

- ↑ Gilliver, Peter (2006). The Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861069-6.

- ↑ [http://travel.nytimes.com/2007/03/23/travel/escapes/23Ahead.html Celebrating Tolkien: Elvish Impersonators]. Retrieved on 2007-04-03.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gilsdorf, Ethan (November 16, 2003). Lord of the Gold Ring. The Boston Globe. Retrieved on 2006-06-16.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Tolkien, J.R.R. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05699-8.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 The Lord of the Rings: Genesis. Retrieved on 2006-06-14.

- ↑ Shippey, Tom (2003). The Road to Middle-earth, Revised and expanded edition. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-25760-8.

- ↑ Carpenter, H. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. George Allen & Unwin. 1981. pp 70—74

- ↑ name="genesis"

- ↑ name="genesis"

- ↑ name="genesis"

- ↑ Tolkien, J.R.R. (2000). The War of the Ring: The History of The Lord of the Rings, Part Three. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08359-6.

- ↑ Template:ME-ref

- ↑ Template:ME-ref

- ↑ "Tolkien Bibliography - LotR - 7 Volumes - 1999-Present". Retrieved on 21 December, 2007.

- ↑ "How many languages have The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings been translated into?". Retrieved on 3 June, 2006.

- ↑ "Influences of Lord of the Ring". Retrieved on 16 April, 2006.

- ↑ "The Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme. They owe more to William Morris and his Huns and Romans, as in The House of the Wolfings or The Roots of the Mountains." The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Letter #19, 31 December 1960

- ↑ Template:ME-ref

- ↑ Shippey, Tom (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien Author of the Century, HarperCollins. ISBN 0-261-10401-2

- ↑ Handwerk, Brian. Lord of the Rings Inspired by an Ancient Epic, National Geographic News, National Geographic Society, 2004-03-01, pp. 1–2. Retrieved on 2006-10-04.

- ↑ "Cultural and Linguistic Conservation". Retrieved on 16 April, 2006.

- ↑ Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography, Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05702-1

- ↑ Template:ME-ref

- ↑ "In the Valley of the Hobbits". Retrieved on 5 October, 2006.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "National Geographic Lord of the Rings -- historical influences". Retrieved on 21 December, 2007.

- ↑ Tolkien, J.R.R. (1991). The Lord of the Rings. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-261-10238-9.

- ↑ "From the Critics". Retrieved on May 30, 2006.

- ↑ "Hobbits in Hollywood". Retrieved on May 13, 2006.

- ↑ Richard Jenkyns. "Bored of the Rings" The New Republic January 28 2002. [1]

- ↑ Wilson, A.N.. Tolkien was not a writer, telegraph.co.uk, Telegraph Group Limited, 2001-11-24. Retrieved on 2006-04-18.

- ↑ "J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biographical Sketch". Retrieved on June 14, 2006.

- ↑ "We Hobbits are a Merry Folk: an incautious and heretical re-appraisal of J. R. R. Tolkien". Retrieved on 9 January, 2006.

- ↑ Moorcock, Michael. "Epic Pooh". Retrieved on 27 January, 2006.

- ↑ Seiler, Andy (December 16, 2003). 'Rings' comes full circle. USA Today. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ Diver, Krysia. Troubled Germans turn to Lord of the Rings, The Guardian, 4 October 2004. Retrieved on 4 October 2013.

- ↑ Cooper, Callista (December 5, 2005). Epic trilogy tops favourite film poll. ABC News Online. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ O'Hehir, Andrew (June 4, 2001). The book of the century. Salon.com. Retrieved on 2006-03-12.

- ↑ "Tolkien's Lord of the Rings: Truth, Myth or Both?" Berit Kjos. Posted December 2001. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ↑ "Tolkien, Racism, & Paranoia". Page 2. Julia Houston. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ↑ Was Tolkien a racist? Were his works? from the Tolkien Meta-FAQ by Steuard Jensen. Last retrieved 2006-11-16

- ↑ "I have the hatred of apartheid in my bones; and most of all I detest the segregation or separation of Language and Literature. I do not care which of them you think White." — The Monsters and the Critics (1983, ISBN 0-04-809019-0)

- ↑ In fact Jordan did not live to complete the series. Warned of this possibility by doctors, he wrote up a detailed outline of the rest of the story, and his widow commissioned Brandon Sanderson to complete the work. He appears as coauthor of the remaining volumes, but in smaller print.

- ↑ 2005, page 43

- ↑ "Do you remember [...] The Lord of the Rings? [...] Well, Io is Mordor [...] There's a passage about "rivers of molten rock that wound their way ... until they cooled and lay like dragon-shapes vomited from the tortured earth." That's a perfect description: how did Tolkien know, a quarter of a century before anyone saw a picture of Io? Talk about Nature imitating Art." (Arthur C. Clarke, 2010: Odyssey Two, Chapter 16 'Private Line')

- ↑ Star Wars Origins - The Lord of the Rings. Star Wars Origins. Retrieved on 2006-09-19.

- ↑ Gary Gygax - Creator of Dungeons & Dragons. Retrieved on 2006-05-28.

- ↑ Douglass, Perry (May 17, 2006). The Influence of Literature and Myth in Videogames. IGN. Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

- ↑ Feist, Raymond (2001). Meditations on Middle-Earth. St. Martin's Press.

- ↑ Carpenter, Humphrey (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-05702-1.

- ↑ Drake, Matt (June 29, 2005). Review of Lord of the Rings. RPGnet. Retrieved on 2006-05-29.

KSF

KSF