The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 4 min

| This article may be deleted soon. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

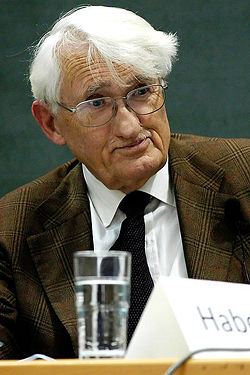

The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere is a book marking a key development in sociology and philosophy and the theory of democracy by German thinker Jürgen Habermas. It was published in 1962 but was not translated into English until 1989. In it, Habermas argues that from about the mid 1600s onwards, there was a phenomenon which evolved during the Renaissance in Western Europe, principally in Britain, France, and later in Germany, as well as the United States and other Western oriented nations. It was spurred on by the growth of democracy and individual liberty and popular sovereignty. It was called the public sphere. The rise of the public sphere[edit]The public sphere was a place between private individuals and government authorities in which people could meet and have rational-critical debates about public matters. Discussions served as a counterweight to political authority and happened physically in face-to-face meetings in coffee houses and cafes and public squares as well as in the media in letters, books, drama, and art.[1] It was a place where the public could think actively and contribute to political discourse; as such, public opinion mattered to politicians and government authorities, and the influence of public opinion had a stabilizing effect on public policy. It began in the late 1600s. Politicians sought to please the public; in addition, unpopular policies could be criticized in books, letters, newspaper editorials, in theater and art, and these criticisms often led to change. A government was seen as legitimate if it heeded the public sphere. Rational-critical debate was a quasi-counterweight to political authority. Habermas saw a vibrant public sphere as a positive force keeping authorities within bounds lest their rulings be ridiculed. According to one account, the bourgeois public sphere was preceded by a literary public sphere. Decline of the public sphere[edit]Habermas argues that the public sphere transformed from a vibrant force into a smaller, diminished area. So while the sense of citizenship widened, and more people tended to be counted as citizens in democratic nations, the public sphere shrunk. Publicity widened with the technological capability of journalism augmented by a revolution in communications technology, but while this happened, individual people had less and less ability to influence developments in politics. A variety of forces have caused this transformation, according to Habermas. Citizenship degenerated from an active relationship characterized by voluntary participation in the political sphere into a world in which people were mostly withdrawn from politics. The welfare state brought new forces into the political arena, and these gathered momentum in the 1840s onwards.

He added:

The changes had profound affects on citizenship. Today, in contrast, there is scant public debate, few public forums, and political discussion has degenerated from a fact-based rational-critical examination of public matters into a consumer commodity. There is the illusion of a public sphere, according to Habermas. Citizens have become consumers, investors, workers. News has become a commodity to be packaged and sold rather than information which helps people remain free. Habermas argues that entertainment is driving out real news and the cult of celebrity has undermined political discussion. His work encompasses many disciplines including political theory, cultural criticism, ethics, gender studies, philosophy, sociology, history, and media studies. Habermas analyzes these developments and points out how different political philosophers, including Hegel and Immanuel Kant and Tocqueville and Mill and Karl Marx described the shift. The addition of new publics which sought to steer public monies towards partisan interests helped undermine the public sphere, according to Habermas. This transformation was part of a larger dialectic in which political changes were made to try to save the liberal constitutional order, but which backfired. Habermas drew on critical theory from the Frankfurt School, which included important thinkers such as Theodor Adorno, who was one of Habermas' teachers.[2] Text[edit]This book was his first major work. It also satisfied the rigorous requirements for a professorship in Germany; in this system, independent scholarly research, usually resulting in a published book, must be submitted, and defended before an academic committee; this process is known as Habilitationsschrift or habilitation. The work was overseen by the political scientist Wolfgang Abendroth, to whom Habermas dedicated it. The book has been reprinted in many languages and has been "enormously influential" despite popular perception that it is difficult to read. See also[edit]References[edit]

|

||||||||

KSF

KSF