Theodore Roosevelt

From Citizendium - Reading time: 34 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 34 min

Theodore Roosevelt Jr., (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), known as T.R. and to the public as Teddy.[1] He was the 26th President of the United States of America and a leader of the progressive wing of the Republican Party and of the Progressive Movement nationally. He served in many roles including New York state legislator and governor of New York, chairman of the US Civil Service Commission, New York City Police Commissioner, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, historian, naturalist, explorer, author, and soldier. Roosevelt is most famous for his personality, his energy, his vast range of interests and achievements, his model of masculinity, and his "cowboy" persona.

As Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy, he prepared for and advocated war with Spain in 1898. He organized and helped command the "Rough Riders" regiment during the Spanish-American War. Returning to New York as a war hero, he was elected Republican governor in 1898. He was a professional historian, a lawyer, a naturalist and explorer of the Amazon; his 35 books[2] include works on outdoor life, natural history, the American frontier, political history, naval history, and his autobiography.

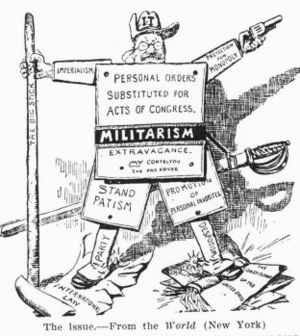

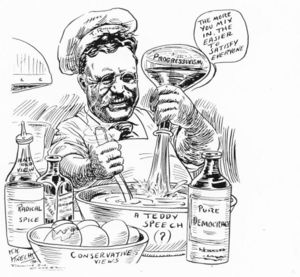

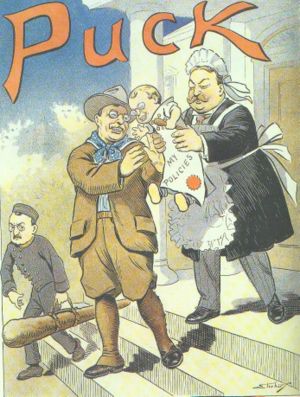

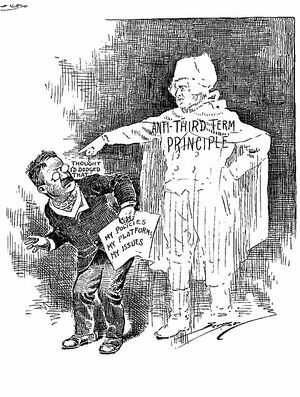

In 1901, as Vice President, Roosevelt succeeded President William McKinley after an assassination. Roosevelt was a Progressive reformer who sought to move the dominant Republican Party into the Progressive camp. He distrusted wealthy businessmen and dissolved 40 monopolistic corporations as a "trust buster." He was clear, however, to show that he did not disagree with trusts and capitalism in principle but was only against their corrupt, illegal practices. His "Square Deal" promised a fair shake for both the average citizen, including regulation of railroad rates and pure foods and drugs, and the businessmen. As an outdoorsman, he promoted the conservation movement, emphasizing efficient use of natural resources. After 1906, he moved left, attacking big business and suggesting the courts were biased against labor unions. In 1910, he broke with his friend and anointed successor William Howard Taft, but lost the Republican nomination to Taft and ran in the 1912 election on his own one-time Bull Moose ticket. Roosevelt lost but pulled so many Progressives out of the Republican Party that Democrat Woodrow Wilson won in 1912, and the conservative faction took control of the Republican Party for the next two decades.

Roosevelt understood the strategic significance of the Panama Canal and negotiated for the US to take control of its construction in 1904; he felt that the Canal's completion was his most important and historically significant international achievement. He was the first American to be awarded the Nobel Prize, winning the Peace Prize in 1906, for negotiating the peace in the Russo-Japanese War.

Historian Thomas Bailey, who disagreed with Roosevelt's policies, nevertheless concluded, "Roosevelt was a great personality, a great activist, a great preacher of the moralities, a great controversialist, a great showman. He dominated his era as he dominated conversations ... the masses loved him; he proved to be a great popular idol and a great vote getter."[3] His image stands alongside George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln on Mount Rushmore.

Childhood, education, and personal life[edit]

Roosevelt was born at 28 East 20th Street New York City on October 27, 1858, the second of four children of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (1831–1877) and Martha Bulloch Roosevelt (1834–1884). He had an elder sister Anna, nicknamed "Bamie" as a child and "Bye" as an adult for being always on the go; and two younger siblings — his brother Elliott Roosevelt (the father of Eleanor Roosevelt) and his sister Corinne Roosevelt Robinson.

The Roosevelts had been in New York since the mid 17th century and had grown with the emerging New York commerce class after the American Revolution. By the 18th Century, the family had grown in wealth, power and influence from the profits of several businesses including hardware and plate-glass importing. The family was strongly Democratic in its political affiliation until the mid-1850s, then joined the new Republican Party. Theodore's father, known in the family as "Thee", was a New York City philanthropist, merchant, and partner in the family glass-importing firm Roosevelt and Son. He was a prominent supporter of Abraham Lincoln and the Union effort during the American Civil War. Theodore's mother Mittie Bulloch was a Southern belle from a slave-owning family in Savannah, Georgia, and had quiet Confederate sympathies. Mittie's brother, Theodore's uncle, James Dunwoody Bulloch, "Uncle Jimmy", was a U.S. Navy officer who became a Confederate admiral and naval procurement agent in Britain. Another uncle Irvine Bulloch was a midshipman on the Confederate raider, CSS Alabama; both remained in exile in England after the war.[4]

Sickly and asthmatic as a youngster, Roosevelt had to sleep propped up in bed or slouching in a chair during much of his early childhood, and had frequent ailments. Despite his illnesses, he was a hyperactive and often mischievous young man. His lifelong interest in zoology was formed at age seven upon seeing a dead seal at a local market. After obtaining the seal's head, the young Roosevelt and two of his cousins formed what they called the "Roosevelt Museum of Natural History". Learning the rudiments of taxidermy, he filled his makeshift museum with many animals that he killed or caught, studied, and prepared for display. At age nine, he codified his observation of insects with a paper titled "The Natural History of Insects".[5]

To combat his poor physical condition, his father compelled the young Roosevelt to take up exercise. To deal with bullies, Roosevelt started boxing lessons. Two trips abroad had a permanent impact: family tours of Europe in 1869 and 1870, and of the Middle East 1872 to 1873. [6]

Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. had a tremendous influence on young Theodore and was a life-long source of inspiration. Of him Roosevelt wrote, "My father, Theodore Roosevelt, was the best man I ever knew. He combined strength and courage with gentleness, tenderness, and great unselfishness. He would not tolerate in us children selfishness or cruelty, idleness, cowardice, or untruthfulness."[7] Roosevelt's sister later wrote, "He told me frequently that he never took any serious step or made any vital decision for his country without thinking first what position his father would have taken."[8]

Young "Teedie" as he was nicknamed as a child, (the nickname "Teddy" was from his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee, and he later harbored an intense dislike for it) was mostly home schooled by tutors and his parents. A leading biographer says: "The most obvious drawback to the home schooling Roosevelt received was uneven coverage of the various areas of human knowledge." He was solid in geography (thanks to his careful observations on all his travels) and very well read in history, strong in biology, French and German, but deficient in mathematics, Latin and Greek.[9] He matriculated at Harvard College in 1876, graduating magna cum laude. His father's death in 1878 was a tremendous blow, but Roosevelt redoubled his activities. He did well in science, philosophy and rhetoric courses but fared poorly in Latin and Greek. He studied biology with great interest and indeed was already an accomplished naturalist and published ornithologist. He had a photographic memory and developed a life-long habit of devouring books, memorizing every detail.[10] He was an unusually eloquent conversationalist who, throughout his life, sought out the company of the smartest men and women. He could multitask in extraordinary fashion, dictating letters to one secretary and memoranda to another, while browsing through a new book. During his adulthood, a visitor would get a not-so-subtle hint that Roosevelt was losing interest in the conversation when he would pick up a book and begin looking at it now and then as the conversation continued.

While at Harvard, Roosevelt was active in numerous clubs, such as rowing and boxing. Other clubs included the Alpha Delta Phi and Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternities. He also edited a student magazine. He was runner-up in the Harvard boxing championship, losing to C.S. Hanks. The sportsmanship Roosevelt showed in that fight was long remembered. Upon graduating from Harvard, Roosevelt underwent a physical examination and his doctor advised him that due to serious heart problems, he should find a desk job and avoid strenuous activity. Roosevelt disregarded the advice and chose to embrace the strenuous life instead.[11]

He graduated Phi Beta Kappa and magna cum laude (22nd of 177) from Harvard in 1880, and entered Columbia Law School. When offered a chance to run for New York Assemblyman in 1881, he dropped out of law school to pursue his new goal of entering public life.[12]

Early public life[edit]

Roosevelt was a Republican activist during his years in the Assembly, writing more bills than any other New York state legislator. Already a major player in state politics, he attended the Republican National Convention in 1884 and fought alongside the Mugwump reformers; they lost to the Stalwart faction that nominated James G. Blaine. Refusing to join other Mugwumps in supporting Democrat Grover Cleveland, the Democratic nominee, he stayed loyal.[13]

First marriage[edit]

On his 22nd birthday, Roosevelt married his first wife, 19-year-old Alice Hathaway Lee, on October 27, 1880, at the Unitarian Church in Brookline, Massachusetts. Alice was the daughter of the prominent banker George Cabot Lee and Caroline Haskell Lee. The couple first met in 1878. He proposed in June 1879. However, Alice waited another six months before accepting the proposal. Alice Roosevelt died exactly four years later, only two days after the birth of their first child, also named Alice. In a tragic coincidence, Roosevelt's mother died of typhoid fever on the same day, also at the Roosevelt family home in Manhattan.

Roosevelt refused to speak his first wife's name again (even omitting her name from his autobiography) and did not allow others to speak of her in his presence. This practice put an early strain on his relationship with his daughter who was given his late wife's name. However, as she grew into adulthood and better understood her father's deep moral convictions, the bond between them became strong. Alice continued to support her father's ideas after his death in 1919.

Later in 1884, Roosevelt left the General Assembly and put his infant daughter Alice in the long-term care of his older sister, Bamie. In letters to Bamie, he would refer to Alice as Baby Lee.

Cowboy life in the Badlands[edit]

Roosevelt moved to his "Maltese Cross" ranch seven miles from Medora in the Badlands of the Dakota Territory to live a more simple life as a rancher and lawman. Roosevelt built a second ranch he named Elk Horn thirty five miles north of the boomtown, Medora, North Dakota. On the banks of the "Little Missouri", Roosevelt learned to ride, rope, and hunt. There, in the waning days of the American Old West, he rebuilt his life and began writing about frontier life for Eastern magazines. As a deputy sheriff, Roosevelt hunted down three outlaws who stole his river boat and were escaping north with it up the Little Missouri River. Capturing them, he decided against hanging them and sending his foreman back by boat, he took the thieves back overland for trial in Dickinson, guarding them forty hours without sleep and reading Tolstoy to keep himself awake. When he ran out of his own books he read a dime store western that one of the thieves was carrying.

While working on a tough project aimed at hunting down a group of relentless horse thieves, Roosevelt came across the famous Deadwood, South Dakota Sheriff Seth Bullock. The two would remain friends for life. After a winter wiped out his herd of cattle and his $60,000 investment (together with those of his competitors), he returned to the East.[14]

In 1885, Roosevelt purchased Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, New York. It would be his home and estate until his death. Roosevelt ran as the Republican candidate for mayor of New York City in 1886 as "The Cowboy of the Dakotas" to assert his manliness. He came in third.

Second marriage[edit]

In 1886 he married his childhood sweetheart, Edith Kermit Carow. They honeymooned in Europe, and Roosevelt climbed Mont Blanc, leading only the third recorded expedition to reach the summit, a feat which resulted in his induction into the British Royal Society.[15] They had five children: Theodore Jr., Kermit, Ethel Carow, Archibald Bulloch "Archie", and Quentin.[16] "Uncle Ted" was the godfather and favorite uncle of Eleanor Roosevelt, whom he gave away in marriage to their fifth cousin Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1905.

Historian[edit]

In the 1880s, he gained recognition as a serious historian. His The Naval War of 1812 (1882) was the standard history for two generations. For that book, Roosevelt undertook extensive and original research going as far as computing British and American man-of-war broadside throw weights.[17] By comparison, however, his hastily-written biographies of Thomas Hart Benton (1887) and Gouverneur Morris (1888) are considered superficial.[18] His major achievement was a four-volume history of the frontier, The Winning of the West (1889-1896), which had a notable impact on historiography as it presented a highly original version of the frontier thesis elaborated upon in 1893 by his friend Frederick Jackson Turner. Roosevelt argued that the harsh frontier conditions had created a new "race": the American people. He was using a Lamarkean model in which new environmental conditions allow a new species to form. His many articles in upscale magazines provided a much-needed income, as well as cementing a reputation as a major national intellectual. He was later chosen president of the American Historical Association.[19]

Return to public life[edit]

In the 1888 presidential election, Roosevelt campaigned for Benjamin Harrison in the Midwest. President Harrison appointed Roosevelt to the Civil Service Commission, where he served until 1895.[20] In his term, he vigorously fought the spoils system in which politicians gave out jobs to supporters. In spite of Roosevelt's support for Harrison's reelection bid in the presidential election of 1892, the winner, Grover Cleveland (a Bourbon Democrat), reappointed him to the same post.

In 1895, he became president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners. During the two years that he held this post, Roosevelt radically changed the way the police department was run. The police force was reputed as one of the most corrupt in America, to which TR introduced new standards of integrity. Roosevelt and his fellow commissioners established new disciplinary rules, created a bicycle squad to police New York's traffic problems and standardized the use of pistols by officers. Roosevelt implemented regular inspections of firearms, annual physical exams, appointed 1,600 new recruits based on their physical and mental qualifications and not on political affiliation, opened the department to ethnic minorities and women, established meritorious service medals, and shut down the corrupt police hostelries. During his tenure a Municipal Lodging House was established by the Board of Charities and Roosevelt required his officers to register with the Board. He also had telephones installed in station houses. Always an energetic man, he made a habit of walking officers' beats late at night and early in the morning to make sure that they were on duty. He became caught up in public disagreements with commissioner Parker, who sought to negate or delay the promotion of many officers put forward by Roosevelt.[21]

[edit]

Roosevelt had always been fascinated by navies and their history. Urged by Roosevelt's close friend, Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge[22], President William McKinley in 1897 appointed Roosevelt to the post of Assistant Secretary of the Navy, the Number 2 job. Because of the inactivity of Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, Roosevelt had virtual control over the department. Roosevelt was instrumental in preparing the Navy for the Spanish-American War[23] and was an enthusiastic proponent of testing the U.S. military in battle, at one point stating "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one".[24]

War in Cuba[edit]

Upon the declaration of war in 1898 that would be known as the Spanish-American War, Roosevelt resigned from the Navy Department and, with the aid of U.S. Army Colonel Leonard Wood, organized the Rough Riders (formally, the "First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment") out of a diverse crew that ranged from cowboys from the Dakotas to Ivy League friends from the city. Originally Roosevelt held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and served under Colonel Wood, but after Wood was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteer Forces, Roosevelt was promoted to Colonel and given command of the Regiment. Under his leadership, the Rough Riders became famous for their dual charges up Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill in July 1898 (the battle was named after the latter hill). Roosevelt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2001 for his actions.[25] He was the only President of the United States to be awarded with America's highest military honor, and the only person in history to receive both his nation's highest honor for military valor and the world's foremost prize for peace.

Governor and Vice President[edit]

Roosevelt re-entered New York state politics and was elected governor of New York in 1898 on the Republican ticket. He made such a concerted effort to root out corruption and "machine politics" that Republican boss Thomas Collier Platt forced him on McKinley as a running mate in the 1900 election, against the wishes of McKinley's manager Senator Mark Hanna. Roosevelt was a powerful campaign asset for the Republican ticket, which defeated William Jennings Bryan in a landslide based on restoration of prosperity at home and a successful war and new prestige abroad. Bryan stumped for Free Silver again, but McKinley's promise of prosperity through the Gold Standard, high tariffs, and the restoration of business confidence proved far more attractive to voters and he enlarged his margin of victory. Bryan had strongly supported the war against Spain, but denounced the annexation of the Philippines as imperialism that would spoil America's innocence. Roosevelt countered with many speeches that argued it was best for the Filipinos to have stability, and the Americans to have a proud place in the world. Roosevelt's few months as Vice President (March to September, 1901) were uneventful.[26] On September 2, 1901, at the Minnesota State Fair, Roosevelt first used in a public speech a saying that would later be universally associated with him: "Speak softly and carry a big stick, and you will go far." Twelve days later, President McKinley would be dead, and Roosevelt would succeed him.

Presidency 1901-1909[edit]

President McKinley was shot by an anarchist, on September 6, 1901. When he first heard of the shooting, Roosevelt had been given a speech in Vermont. Assured by McKinley's people that the crisis had past and that the President would recover, Roosevelt had gone on to a planned family camping and hiking trip to Mount Marcy in the Adirondacks when a runner finally caught up with him and told him that McKinley's condition had greatly worsened and that he was on his death bed. Not wanting to simply show up in Buffalo and wait on McKinley's death, Roosevelt was pondering with his wife, Edith, how best to respond to this turn of events, when additional news reached him that McKinley would soon die. Roosevelt was rushed by a series of stagecoaches to North Creek train station. At the station, Roosevelt was handed a telegram that said only that the President had died. Turning the telegram upside down and reading it again, Roosevelt expressed a sense of helplessness that the telegram contained no additional information and said only that McKinley had died at 2:30 a.m. that morning. Officially having learned that he would be the next President of the United States, from North Creek, he continued by train to Buffalo where he swore the oath of office. Senator Mark Hanna lamented that "that damned cowboy is president now," but quickly cut a deal with the new master of the party; both men wanted the 1904 nomination.[27] Roosevelt was the youngest person to assume the presidency, at 42, and he promised to continue McKinley's cabinet and his basic policies. Roosevelt did so, but after reelection in 1904, he moved to the political left, stretching his ties to the Republican Party's conservative leaders.[28]

Anthracite coal strike of 1902[edit]

A national emergency was averted in 1902 when Roosevelt found a compromise to the anthracite coal strike by the United Mine Workers of America that threatened the heating supplies of most urban homes. Roosevelt called the mine owners and the labor leaders to the White House and negotiated a compromise. Miners were on strike for 163 days before it ended; they were granted a 10% pay increase and a 9-hour day (from the previous 10 hours), but the union was not officially recognized and the price of coal went up.[29]

Square Deal[edit]

Theodore Roosevelt promised to continue McKinley's program, and at first he worked closely with McKinley's men. His 20,000-word address to the Congress in December 1901, asked Congress to curb the power of trusts "within reasonable limits." They did not act but Roosevelt did, issuing 44 lawsuits against major corporations; he was called the "trust-buster."

Mark Hanna was the rival power in the Republican party. Hanna died, and Roosevelt had an easy renomination and reelection in 1904. He won 336 of 476 electoral votes, and 56.4% of the total popular vote. He therefore became the first President who came into office due to the death of his predecessor to be elected in his own right.

Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities.

Regulation of industry[edit]

Roosevelt firmly believed: "The Government must in increasing degree supervise and regulate the workings of the railways engaged in interstate commerce." Inaction was a danger, he argued: "Such increased supervision is the only alternative to an increase of the present evils on the one hand or a still more radical policy on the other."[30] His biggest success was passage of the Hepburn Act of 1906, granting the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) the power to set maximum railroad rates; it also stopped free passes given to friends of the railroad. At that time it was universally assumed that railroads would continue to be a vast and powerful force. No one dreamed they would eventually be challenged by truck and automobile traffic, and hence struggle to survive under the provisions of the Hepburn Act designed to protect merchants and consumers.

In response to public clamor, Roosevelt pushed Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, as well as the Meat Inspection Act of 1906. These laws provided for labeling of foods and drugs, inspection of livestock and mandated sanitary conditions at meatpacking plants. Congress replaced Roosevelt's proposals with a version supported by the major meatpackers who worried about the overseas markets, and did not want small unsanitary plants undercutting their domestic market.[31]

Conservationist[edit]

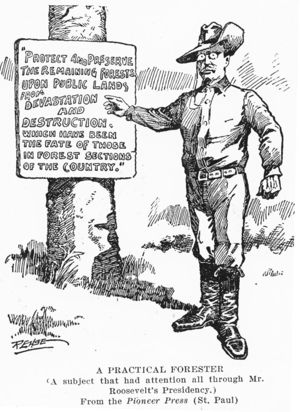

Roosevelt was the first American president to consider the long-term needs for efficient conservation of national resources, winning the support of fellow hunters and fishermen to bolster his political base. Roosevelt was the last trained observer to ever see a passenger pigeon, and in 1903, he created the first National Bird Preserve, (the beginning of the Wildlife Refuge system), on Pelican Island, Florida. Assuming the conservationist role was a natural step for him, and he decided that it was overdue to put the issue high on the national agenda. He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter Gifford Pinchot. Roosevelt urged congress to establish the United States Forest Service (1905), to manage government forest lands, and he appointed Gifford Pinchot to head the service. Roosevelt set aside more land for national parks and national forests than all of his predecessors combined, 194 million acres. In all, by 1909, the Roosevelt administration had created an unprecedented 42 million acres of national forests, 53 national wildlife refuges and 18 areas of "special interest", including the Grand Canyon. The Theodore Roosevelt National Park in the Badlands commemorates his conservationist philosophy. In 1903, Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, but he rejected Muir's philosophy that privileged nature, and emphasized instead the more efficient use of nature. In 1907, with Congress about to block him, Roosevelt hurried to designate 16 million acres (65,000 km²) of new national forests. In May 1908, he sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on the most efficient planning, analysis and use of water, forests and other natural resources. Roosevelt explained, "There is an intimate relation between our streams and the development and conservation of all the other great permanent sources of wealth." During his presidency, Roosevelt promoted the nascent conservation movement in essays for Outdoor Life magazine. Roosevelt, like Pinchot (but unlike Muir), believed in the more efficient use of natural resources by corporations like lumber companies. To Roosevelt, conservation meant more and better usage and less waste, and a long-term perspective

Foreign policy[edit]

Roosevelt's administration was marked by an active approach to foreign policy. Roosevelt saw it as the duty of more developed ("civilized") nations to help the underdeveloped ("uncivilized") world move forward. In Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and the Panama Canal Zone, he used the Army's medical service, under Walter Reed and William C. Gorgas, to eliminate the yellow fever menace and install a new regime of public health. He used the army to build up the infrastructure of the new possessions, building railways, telegraph and telephone lines, and upgrading roads and port facilities.

Roosevelt dramatically increased the size of the navy, forming the new warships into a "Great White Fleet" for display purposes and sending it on a world tour in 1907. This display was designed as a show of force to impress the Japanese. Yet, the ships were almost forced to return because of the inadequacy of American ports in the Pacific.[32]

Roosevelt Corollary and peace work[edit]

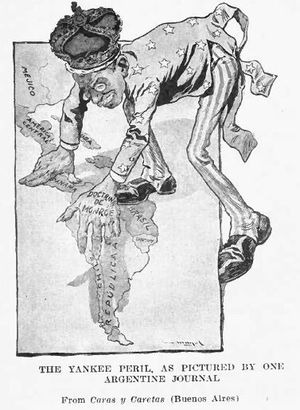

The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was a substantial alteration (called an "amendment") of the Monroe Doctrine by Roosevelt in 1904. Roosevelt's extension of the Monroe Doctrine asserted the right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of small nations in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts and were at risk of intervention by European powers. The alternative was intervention by European powers, especially Britain and Germany, which loaned money to the countries that did not repay. The catalyst of the new policy was Germany's aggressiveness in the Venezuela affair of 1902-03. The intervention took the form of takeover of the customs collection, and disbursement of the funds to the debtors and claimants. The policy was unpopular abroad (Ricard 2006).

Mitchener and Weidenmier (2006) show the economic benefits to the small countries. The average debt price for countries under the US "sphere of influence" rose by 74% in response to the pronouncement and actions to make it credible. That is, their bonds rose 74% because buyers now believed they would be repaid. The increase in financial stability reduced internal conflict because political factions could not count on winning control of the national treasury if they won a civil war. The program spurred export growth and better fiscal management, but debt settlements were driven primarily by gunboat diplomacy.

Roosevelt's December 1904 Annual message to Congress declared:

- All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. If a nation shows that it knows how to act with reasonable efficiency and decency in social and political matters, if it keeps order and pays its obligations, it need fear no interference from the United States. Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, ultimately require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.

The point was that when small countries got deeply into debt the U.S. would not allow any European nation to intervene to collect the debts; it would do so itself by takling over the customs system and scheduling a fair payment schedule with minimal corruption and fraud. Economically it boosted the region because lenders knew they would be repaid. The average debt price for countries under the US "sphere of influence" rose by 74% in response to the Roosevelt Corollary. This policy change shows that the United States subsequently acted as a regional hegemon and provided the global public increased financial stability and peace. Reduced conflict spurred export growth and better fiscal management, but debt settlements were driven primarily by gunboat diplomacy. An initially defensive dictum had therefore been turned into an aggressive policy by a man who had long pondered America's standing and role in the world. Fundamentally it reflected a new, innovative conception of security and defense, as well as changing geopolitical conditions. The catalysts of that drastic mutation were the necessary protection of the projected isthmian canal and Germany's aggressiveness in the Caribbean. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was ended by President Herbert Hoover in 1931 with the Clark Amendment. [33]

Roosevelt gained international praise for helping negotiate the end of the Russo-Japanese War, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Roosevelt later arbitrated a dispute between France and Germany over the division of Morocco.

Panama Canal[edit]

Roosevelt's most famous foreign policy initiative, was the construction of the Panama Canal, which upon its completion shortened the route of freighters between San Francisco, California and New York City by 8,000 miles (13,000 km). It integrated the West Coast into the national economy (which was still based in the northeast), and opened a new route to Asia.

Colombia first proposed the canal in their country as opposed to rival Nicaragua, and Colombia signed a treaty for an agreed-upon sum. At that time, Panama was a province of Colombia. According to the treaty, in 1902, the U.S. was to buy out the equipment and excavations from France, which had been attempting to build a canal since 1881. The Colombian Senate balked at the price and asked for an extra $10 million over the original agreed upon price. When Roosevelt refused to re-negotiate the price, the Colombian politicians proposed cutting the original French company out of the deal and giving that difference to Colombia. The original deal stipulated that the French company was to be reasonably compensated. Realizing that the Colombian Senate was no longer bargaining in good faith, Roosevelt tired of these last-minute attempts by the Colombians to cheat the French out of their entire investment.

Roosevelt went along with the alternative plan of Panamanians to help Panama declare independence from Colombia in 1903. A brief revolution, of only a few hours, followed the declaration, and Colombian soldiers were bribed $50 each to lay down their arms. On November 3, 1903, the Republic of Panama was created. Shortly thereafter, a treaty was signed with Panama. The U.S. paid $10 million to secure rights to build on and control the Canal Zone. Construction began in 1904 and was completed in 1914.

It took a decade to build the Canal because illness, especially yellow fever and malaria, spread by mosquitoes. Roosevelt sent the U.S. Army to solve the issue, which it did by systematically eradicating breeding areas.

Life in the White House[edit]

Roosevelt relished the presidency and seemed to be everywhere at once. He took Cabinet members and friends on long, fast-paced hikes, boxed in the state rooms of the White House, romped with his children, and read voraciously. In 1904, he was permanently blinded in his left eye during one of his boxing bouts, but this injury was kept from the public at the time.[34] His many enthusiastic interests and limitless energy led one ambassador to wryly explain, "You must always remember that the President is about six."[35]

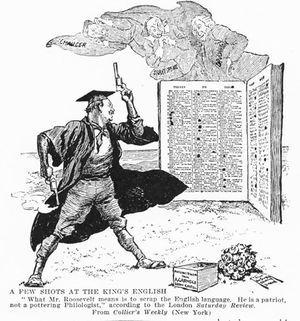

During his presidency, Roosevelt tried but did not succeed to advance the cause of simplified spelling. He tried to force government to adopt the system, sending an order to the Public Printer to use the system in all public documents. The reform annoyed the public, forcing him to rescind the order. Roosevelt told his friend, literary critic Brander Matthews, one of the chief advocates of the reform, "I could not by fighting have kept the new spelling in, and it was evidently worse than useless to go into an undignified contest when I was beaten. Do you know that the one word as to which I thought the new spelling was wrong — thru — was more responsible than anything else for our discomfiture?" Next summer Roosevelt was watching a naval review when a launch marked "Pres Bot" chugged ostentatiously by. The President waved and laughed with delight.[36]

Roosevelt's oldest daughter, Alice, was a controversial character during Roosevelt's stay in the White House. When friends asked if he could rein in his elder daughter, Roosevelt said, "I can be President of the United States, or I can attend to Alice." In turn, Alice said of him that he always wanted to be "the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral."[37]

Roosevelt's contribution to the White House was the construction of the original West Wing, which he had built to free up the second floor rooms in the residence that formerly housed the president's staff. He and Edith also had the entire house renovated and restored to the federal style, tearing out the Victorian furnishings and details (including Tiffany windows) that had been installed over the previous three decades.

Post-presidency[edit]

African safari[edit]

In March 1909, shortly after the end of his second term, Roosevelt left New York for a safari in Africa. Financed by Andrew Carnegie and by his own proposed writings, Roosevelt hunted for specimens for the Smithsonian Institution and for the American Museum of Natural History in New York. His party, which included scientists from the Smithsonian and was led by Frederick Selous, the famous big game hunter and explorer, killed or trapped over 11,397 animals, from insects and moles to hippopotamuses and elephants. 512 of the animals were big game animals, of which 262 were consumed by the expedition. This included six white rhinos. Tons of salted animals and their skins were shipped to Washington; the number of animals was so large, it took years to mount them. The Smithsonian was able to share many duplicate animals with other museums. Of the large number of animals taken, Roosevelt said, "I can be condemned only if the existence of the National Museum, the American Museum of Natural History, and all similar zoological institutions are to be condemned."[38] Although based in the name of science, there was a large social element to the safari. Interaction with many native peoples, local leaders, renowned professional hunters, and land owning families made the safari much more than a hunting excursion. Roosevelt wrote a detailed account of this adventure; "African Game Trails" describes the excitement of the chase, the people he met, and flora and fauna he collected in the name of science.

Republican Party rift[edit]

Roosevelt certified William Howard Taft to be a genuine "progressive" in 1908, when Roosevelt pushed through the nomination of his Secretary of War for the Presidency. Taft easily defeated three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan. Taft had a different progressivism, one that stressed the rule of law and preferred that judges rather than administrators or politicians make the basic decisions about fairness. Taft usually proved a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and lacked the energy and personal magnetism, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk severe tensions inside the Republican Party—pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against merchants and consumers—he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, and then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne-Aldrich tariff of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator Nelson Aldrich and big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best tariff ever. Again he had managed to alienate all sides. While the crisis was building inside the Party, Roosevelt was touring Africa and Europe, so as to allow Taft to be his own man.[39]

Unlike Roosevelt, Taft never attacked business or businessmen in his rhetoric. However, he was attentive to the law, so he launched 90 antitrust suits, including one against the largest corporation, U.S. Steel, for an acquisition that Roosevelt had personally approved. Consequently, Taft lost the support of antitrust reformers (who disliked his conservative rhetoric), of big business (which disliked his actions), and of Roosevelt, who felt humiliated by his protégé. The left wing of the Republican Party began agitating against Taft. Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin created the National Progressive Republican League (precursor to the Progressive Party (United States, 1924)) to defeat the power of political bossism at the state level and to replace Taft at the national level. More trouble came when Taft fired Gifford Pinchot, a leading conservationist and close ally of Roosevelt. Pinchot alleged that Taft's Secretary of Interior Richard Ballinger was in league with big timber interests. Conservationists sided with Pinchot, and Taft alienated yet another vocal constituency.

Roosevelt, back from Europe, unexpectedly launched an attack on the federal courts, which deeply upset Taft. Not only had Roosevelt alienated big business, he was also attacking both the judiciary and the deep faith Republicans had in their judges (most of whom had been appointed by McKinley, Roosevelt or Taft.) In the 1910 Congressional elections, Democrats swept to power, and Taft's reelection in 1912 was increasingly in doubt. In 1911, Taft responded with a vigorous stumping tour that allowed him to sign up most of the party leaders long before Roosevelt announced.

Election of 1912[edit]

Late in 1911, Roosevelt finally broke with Taft and LaFollette and announced himself as a candidate for the Republican nomination. But Roosevelt had delayed too long, and Taft had already won the support of most party leaders in the country. Because of LaFollette's nervous breakdown on the campaign trail before Roosevelt's entry, most of LaFollette's supporters went over to Roosevelt, the new progressive Republican candidate.

Roosevelt, stepping up his attack on judges, carried 9 of the states with preferential primaries, LaFollette took two, and Taft only one. The 1912 Primaries represented the first extensive use of the Presidential Primary, a reform achievement of the progressive movement. However, these primary elections, while demonstrating Roosevelt's popularity with the electorate, were in no ways as important as primaries are today. First of all, there were fewer states where the common voter was given a forum to express himself, such as a primary. Many more states selected convention delegates either at party conventions, or in caucuses, which were not as open as today's caucuses. So while the man in the street still adored Roosevelt, most professional Republican politicians were supporting Taft, and they proved difficult to upset in non-primary states.

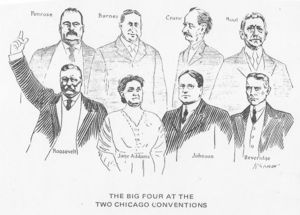

At the Republican Convention in Chicago, despite being the incumbent, Taft's victory was not immediately assured. But after two weeks, Roosevelt, realizing that he would not be able to win the nomination outright, asked his followers to leave the convention hall. Roosevelt, along with key allies such as Pinchot and Albert Beveridge created the Progressive Party, structuring it as a permanent organization that would field complete tickets at the presidential and state level. It was popularly known as the "Bull Moose Party", which got its name after Roosevelt told reporters, "I'm as tough as a bull moose." He brushed off charges he was violating the no-third term tradition set by Washington.

At the convention Roosevelt cried out, "We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord." The crusading rhetoric resonated well with the delegates, many of them long-time reformers, crusaders, activists and opponents of politics as usual. Included in the ranks were Jane Addams and many other feminists and peace activists. The platform echoed Roosevelt's 1907-08 proposals, calling for vigorous government intervention to protect the people from the selfish interests.[40]

- "To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day." - 1912 Progressive Party Platform.[41] and quoted again in his autobiography[42] where he continues "'This country belongs to the people. Its resources, its business, its laws, its institutions, should be utilized, maintained, or altered in whatever manner will best promote the general interest.' This assertion is explicit. ... Mr. Wilson must know that every monopoly in the United States opposes the Progressive party. ... I challenge him ... to name the monopoly that did support the Progressive party, whether ... the Sugar Trust, the Steel Trust, the Harvester Trust, the Standard Oil Trust, the Tobacco Trust, or any other. ... Ours was the only programme to which they objected, and they supported either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Taft."

While campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin on October 14, 1912, a saloonkeeper failed in an assassination attempt on Roosevelt. Roosevelt was hit but the bullet lodged in his chest only after hitting both his steel eyeglass case and a copy of his speech he was carrying in his jacket. Roosevelt refused to go to the hospital, and delivered his scheduled speech. He spoke vigorously for ninety minutes. His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose."

Roosevelt failed to move the political system in his direction. He did win 4.1 million votes (27%), compared to Taft's 3.5 million (23%). However, Wilson's 6.3 million votes (42%) were enough to garner 435 electoral votes. Roosevelt had 88 electoral votes to Taft's 8 electoral votes. But Pennsylvania was Roosevelt's only Eastern state; in the Midwest he carried Michigan, Minnesota and South Dakota; in the West, only California and Washington; he did not win any Southern states. TR pulled so many progressives out of the Republican party that it took on a much more conservative cast for the next generation.

1913-1914 South American Expedition[edit]

His popular book Through the Brazilian Wilderness describes his expedition into the Brazilian jungle in 1913 as a member of the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition co-named after its leader, Brazilian explorer Cândido Rondon. The book describes all of the scientific discovery, scenic tropical vistas and exotic flora, fauna and wild life experienced on the expedition. A friend, Father John Augustine Zahm, a Catholic priest, had searched for new adventures and found them in the forests of South America. To finance the expedition, Roosevelt received support from the American Museum of Natural History, promising to bring back many new animal specimens. Once in South America, a new far more ambitious goal was added: to find the headwaters of the Rio da Duvida, the "River of Doubt," and trace it north to the Madiera and thence to the Amazon River. It was later renamed Rio Roosevelt. The initial expedition started, probably unwisely, on December 9, 1913, at the height of the rainy season. The trip up the River of Doubt started at the end of February 27, 1914.

During the trip up the river, Roosevelt contracted malaria and a serious infection resulting from a minor leg wound. These illnesses so weakened Roosevelt that, by six weeks into the expedition, he had to be attended day and night by the expedition's physician and Kermit. Upon his return to New York, friends and family were startled by Roosevelt's physical appearance and fatigue. Roosevelt wrote to a friend that the trip had cut his life short by ten years. He might not have really known just how accurate that analysis would prove to be, because the effects of the South America expedition had so greatly weakened him that they significantly contributed to his declining health. For the rest of his life, he would be plagued by flareups of malaria and leg inflammations so severe that they would require hospitalization.[43]

Writer[edit]

Despite his weakened condition and slow recovery from his South America expedition, Roosevelt continued to write with passion on subjects ranging from foreign policy to the importance of the national park system. As an editor of Outlook magazine, he had weekly access to a large, educated national audience. In all, Roosevelt wrote about 18 books (each in several editions), including his Autobiography, Rough Riders and History of the Naval War of 1812, ranching, explorations, and wildlife. His most important book was the 4 volume narrative The Winning of the West, which traced the origin of a new "race" of Americans to frontier conditions in the 18th century.

World War I[edit]

see World War I, American entry

Roosevelt angrily complained about the foreign policy of President Wilson, calling it "weak". This caused him to develop an intense dislike of Woodrow Wilson. When World War I began in 1914, Roosevelt strongly supported Britain, France and the Allies because he admired their fight for civilization; he demanded a harsher policy against Germany, especially regarding submarine warfare. In 1916, he campaigned energetically for Charles Evans Hughes and repeatedly denounced those Irish-Americans and German-Americans whose pleas for neutrality Roosevelt said were unpatriotic because they put the interest of Ireland and Germany ahead of America's. He insisted that one had to be 100% American, not a "hyphenated American" who juggled multiple loyalties. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Roosevelt sought to raise a volunteer infantry division, but Wilson refused.[44]

Roosevelt's attacks on Wilson helped the Republicans win control of Congress in the off-year elections of 1918. Roosevelt was popular enough to seriously contest the 1920 Republican nomination, but his health was broken by 1918 because of the lingering malaria. His son Quentin, a daring pilot with the American forces in France, was shot down behind German lines in 1918. Quentin was his youngest son and probably the most like him. It is said that the death of his son distressed him so much that Roosevelt never recovered from his loss.[45]

Death[edit]

His health declined severely in 1918. On January 6, 1919, at the age of 60, Roosevelt died in his sleep of a coronary embolism at Oyster Bay. Upon receiving word of his death, his son, Archie, telegraphed his siblings simply, "The old lion is dead."[46] Woodrow Wilson's vice president at the time Thomas R. Marshall said of his death "Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight."[47] He was buried in nearby Young's Memorial Cemetery.

He attended Presbyterian Church until the age of 16. Later in life, when Roosevelt lived at Oyster Bay he attended an Episcopal church with his wife. While in Washington he attended services at Grace Reformed Church.[48] He was an active Freemason.

Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in pursuing what he called "the strenuous life." To this end, he exercised regularly and took up boxing, tennis, hiking, rowing, polo, and horseback riding. He was an enthusiastic singlestick player and in 1905 showed up at a White House reception with his arm bandaged after a bout with General Leonard Wood. As governor of New York, he boxed with sparring partners several times a week, a practice he regularly continued as President until one blow detached his left retina, leaving him blind in that eye (a fact not made public until many years later).[49]

The strenuous ideal led him to promote the scouting movement. The Boy Scouts of America gave him the title of Chief Scout Citizen, the only person to hold such title. One early Scout leader said, "The two things that gave Scouting great impetus and made it very popular were the uniform and Teddie Roosevelt's jingoism."[50]

Roosevelt was also an avid reader, reading tens of thousands of books, at a rate of several a day in multiple languages. Along with Thomas Jefferson Roosevelt is often considered the most well read of any American politician.[51]

Legacy[edit]

For his gallantry at San Juan Hill, Roosevelt's commanders recommended him for the Medal of Honor, but he did not get it. In the late 1990s, Roosevelt's supporters again took up the flag on his behalf and overcame opposition from elements within the U.S. Army and the National Archives. In January 2001, President Bill Clinton awarded Theodore Roosevelt the Medal of Honor posthumously for his charge up San Juan Hill, Cuba, during the Spanish-American War.

Roosevelt's legacy includes several other important commemorations. Roosevelt was included with George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln at the Mount Rushmore Memorial, designed in 1927 (and funded by a Republican Congress). The United States Navy named two ships for Roosevelt: the USS Theodore Roosevelt SSBN-600, a submarine was in commission from 1961 to 1982; and the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71), an aircraft carrier that has been on active duty in the Atlantic Fleet since 1986.

The [Roosevelt Memorial Association was founded in 1919 to preserve Roosevelt's legacy. The Association preserved Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site, his "Sagamore Hill" home, papers, and memoriabilia. The main collection of TR manuscripts are at the Harvard College Library.

Overall, historians credit Roosevelt for changing the nation's political system by increasing the power of the presidency and making character as important as the issues. His notable accomplishments include trust-busting and conservationism. However, he has been criticized for his interventionist and imperialist approach to nations he considered "uncivilized." Even so, history and legend have been kind to him. His friend, historian Henry Adams, proclaimed, "Roosevelt, more than any other living man ... showed the singular primitive quality that belongs to ultimate matter — the quality that mediǣval theology assigned to God — he was pure act." Historians typically rank Roosevelt among the top five presidents.[52][53]

Popular culture[edit]

Roosevelt's 1901 saying "Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick" is still being occasionally quoted by politicians and columnists in different countries - not only in English but also in translation to various other languages. For example, following the Second Lebanon War of August 2006, opponents of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert accused him of "Speaking loudly and carrying a small stick."

The phrase is also used in a popular Bugs Bunny Cartoon in which Bugs runs for office against a crooked Yosemite Sam. Bugs in the dress of Roosevelt proclaims the phrase and Sam runs in and says "I have a bigger stick and I use it too!" Then Sam proceeds to bop Bugs with the stick on the top of the head.

As a charismatic President often considered larger than life, Roosevelt (or characters using his name loosely based on him) has appeared in numerous fiction books, television shows, films, and other media of popular culture.

TR is a major character in Harry Turtledove's fictional Timeline-191 alternate history, along with Caleb Carr's novels The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness, and is the protagonist of Benito Cereno's Tales From the Bully Pulpit comic book. In the comic play and movie Arsenic and Old Lace part of the zany atmosphere is created by a character who holds the delusion that he is Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt appeared as a guest host in the Histeria! episode "The Teddy Roosevelt Show". The episode opened with a sketch where Roosevelt meets with the show's "writers", and it featured a sketch in which Roosevelt appears as Panama Teddy (a play on Indiana Jones) to help with the construction of the Panama Canal, and also a song based on his nickname "Trust Buster" (sung to the tune of the theme from Ghostbusters). Also, the episode "Presidential People" included a song about Roosevelt, named after his catch phrase, "Bully!" (which, as Toast put it, he liked to say instead of "cool").

Roosevelt and his daughter were the title characters in the short-lived 1987 Broadway musical Teddy & Alice.

Filmmaker John Milius directed two films in which Roosevelt was a central character: The Wind and the Lion (1975) in which he was played by Brian Keith; and Rough Riders ]] (1997) in which he was played by Tom Berenger.

Roosevelt's lasting popular legacy is the stuffed toy bears (teddy bears), named after him following an incident on a hunting trip in 1902. Roosevelt famously refused to kill a captured black bear simply for the sake of making a kill. Bears and later bear cubs became closely associated with Roosevelt in political cartoons thereafter.[54]

On June 26, 2006, Roosevelt, once again, made the cover of TIME magazine with the lead story, "The Making of America—Theodore Roosevelt—The 20th Century Express": "At home and abroad, Theodore Roosevelt was the locomotive President, the man who drew his flourishing nation into the future."[55]

Claude Akins played him in Incident at Victoria Falls (1991 TV film).

Roosevelt is also in the movie Night at the Museum, played by Robin Williams, where he helps out Ben Stiller's character throughout the night. He has also developed a crush on Sacagawea (played by Mizuo Peck).

Trivia[edit]

- Proper pronunciation of the name Roosevelt - In a letter to the Rev. William W. Moir, dated October 10, 1898, Theodore Roosevelt wrote, "As for my name, it is pronounced as if it was spelled "Rosavelt." That is in three syllables. The first syllable as if it was "Rose." This letter can be found on pages 534-535 of the Theodore Roosevelt Cyclopedia, a work compiled by the Theodore Roosevelt Association and found online at http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org under the cyclopedia section.

- On September 3, 1902, a landau carrying Roosevelt and Secret Service Operative William Craig was struck by a trolley in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Craig was killed and Roosevelt was injured.

- In 1906-1907, when there were disagreements between Roosevelt and Senator Ben Tillman over the railroad rate bill, and also controversy between Roosevelt and "nature fakers," the press coined the term "Ananias Club," which meant "liar."

- Roosevelt was a Judo brown belt.

- Oscar S. Straus became the first Jew appointed as a Cabinet Secretary.

- In 1902, in response to the assassination of President McKinley, Roosevelt became the first president to be under constant Secret Service protection.

- In 1906, he made the first trip, by a President, outside the United States, visiting Panama to inspect the construction progress of the Panama Canal.

- He was the first President to refer to the White House as such on his official stationery. Until then the mansion had been referred to simply as 'The President's House'

- Theodore Roosevelt The Lion in White House (2006), a novel by Vichey about Roosevelt's adventures, thrilling stories, and about his activities in his domains, was published in Cambodia in the Khmer language.

- Roosevelt's first appearance on US currency was on the reverse of the Mount Rushmore commemorative dollar and half dollar.

- He is the fifth cousin of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Media[edit]

Theodore Roosevelt's voice can be heard in several speeches from the Vincent Voice Library at Michigan State University: http://www.lib.msu.edu/vincent/presidents/index.htm

See also[edit]

- Progressive Era

- William Howard Taft

- Republican Party (United States), history

- U.S. Progressive Party

- Fourth Party System

- Progressive movement

- President of the United States of America

- President of the United States of America/Catalogs

Notes[edit]

- ↑ According to Roosevelt himself, his last name is pronounced "Rose-a-velt," i.e. [ˈroʊ.zə.ˌvɛlt]. See Inogolo.

- ↑ See list at [1]

- ↑ Thomas A. Bailey, Presidential Greatness (1966) p. 308

- ↑ . Pringle (1931) p. 11

- ↑ "TR's Legacy—The Environment". Retrieved March 6, 2006.

- ↑ Brands (2001) pp. 31-34

- ↑ Roosevelt, Autobiography, p. 13.

- ↑ "The Film & More: Program Transcript Part One". Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ↑ Brands (2001) p. 49–50

- ↑ Brands p. 62

- ↑ Morris The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt

- ↑ Brands, (2001) pp 123–29

- ↑ Brands (2001) p. 190; Edward Kohn, "Crossing the Rubicon: Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and the 1884 Republican National Convention." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 2006 5(1): 18-45. Issn: 1537-7814

- ↑ Brands (2001) ch 9; Morris, Rise of TR, 241-250

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910 Edition, Topic: Theodore Roosevelt

- ↑ Although Roosevelt's father was also named Theodore Roosevelt, he died while the future president was still childless and unmarried, so the future President Roosevelt took the suffix of Sr. and subsequently named his son Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

- ↑ See The Naval War of 1812, via Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Pringle (1931) p 116

- ↑ Lee M. Liberman, "Theodore Roosevelt as an American Historian." PhD dissertation Washington U. 2004. 482 pp. DAI 2005 65(7): 2736-A. DA3139854

- ↑ Brands (2001) ch 10

- ↑ Brands ch 11

- ↑ Wikipedia has an extensive article on Henry Cabot Lodge.

- ↑ Brands ch 12

- ↑ See [2] and [3]

- ↑ Brands ch 13

- ↑ As governor he met Winston Churchill; they did not become friends perhaps because they were so much alike. Brands ch 14-15

- ↑ Pringle p 239; Hanna was outmaneuvered--and died early.

- ↑ Brands ch 16

- ↑ Brands ch 17

- ↑ Annual Message December 1904

- ↑ Blum 1980 pp 43-44

- ↑ See Edward S Miller,War Plan Orange (Annapolis, 1991)

- ↑ Kris James Mitchener and Marc Weidenmier, "Empire, Public Goods, and the Roosevelt Corollary." Journal of Economic History 2005 65(3): 658-692. Issn: 0022-0507; Serge Ricard, "The Roosevelt Corollary." Presidential Studies Quarterly 2006 36(1): 17-26. Issn: 0360-4918

- ↑ Brands, (1997) 565

- ↑ Cecil Spring Rice, The Letters and Friendships of Sir Cecil Spring-Rice, (1929) p 437

- ↑ Pringle 465-7; Brands 555ff

- ↑ Carol Felsenthal, Princess Alice: The Life and Times of Alice Roosevelt Longsworth (1988) pp. 60, 105

- ↑ Patricia O'Toole, (2005) p. 67

- ↑ Brands (2001) ch 26

- ↑ Mowry (1946)

- ↑ O'TOOLE, PATRICIA, "The War of 1912," TIME in Partneship with CNN, Jun. 25, 2006.

- ↑ Roosevelt, An Autobiography: ch 15.

- ↑ O'Toole, (2005).

- ↑ Brands 781-4; Cramer, C.H. Newton D. Baker (1961) 110-113

- ↑ Dalton, (2002)p 507

- ↑ Dalton, (2002) p. 507

- ↑ Manners, William. TR and Will: A Friendship that Split the Republican Party. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1969.

- ↑ "The Religious Affiliation of Theodore Roosevelt U.S. President". Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ↑ Brand (2001) p 565.

- ↑ Larson, Keith (2006). "Theodore Roosevelt". Retrieved March 6, 2006.

- ↑ David H. Burton, The Learned Presidency 1988, p 12.

- ↑ The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (2005). "Biography: Impact and Legacy". Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ↑ "Legacy".

- ↑ "History of the Teddy Bear". Retrieved March 7, 2006.

- ↑ Editors (2006). Month=June&Date=26 "The Making of America—Theodore Roosevelt—The 20th Century Express". Retrieved March 26, 2006.

KSF

KSF