Turkey and refugees from Nazis

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 5 min

Einstein's pleas[edit]

Albert Einstein in the 1930s played a role in saving a number of intellectuals through various safe-havens including one provided by the government of Turkey. He maintained a correspondence with them and later helped place some of these individuals at US institutions. To attain these goals he at times had to lend his name and reputation to American institutions he knew would not hire any Jews as professors.

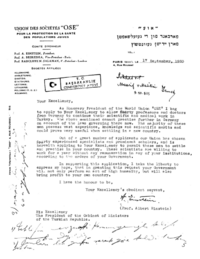

A recently discovered Albert Einstein letter to İsmet İnönü, Prime Minister of Turkey

A letter dated September 17, 1933 carrying Albert Einstein's signature, but not written by Einstein,[1] pleaded for Turkey to invite “forty experienced specialists and prominent scholars... to settle and practice in your country."[2] The hand-written Turkish annotations indicate İnönü transferred the letter to the Ministry for National Education on October 9, 1933. The other annotations are attributable to Reşit Galip, the sitting Minister. One says: “this proposal is incompatible with clauses [in the existing laws],” another: “[i]t is impossible to accept it due to prevailing conditions,” indicating that at the outset the proposal was rejected by the Ministry.

Prime Minister İsmet İnönü responded on November 14, 1933, saying "Although I accept that your proposal is very attractive, I have to tell you that I see no possibility of rendering it compatible with the laws and regulations of our country. ... We have now more than 40 professors and physicians under contract in our employ. Most of them find themselves under the same political conditions while having similar qualifications and capacities.... Therefore I regret to say that it would be impossible to employ more personnel from among these gentlemen under the current conditions we find ourselves in."

That is, Turkey rejected his plea.

The outcome[edit]

On the face of it İnönü’s letter appears to have closed the doors to Einstein’s plea. However, matters did not end with the position taken by İnönü. The Universite Reformu conducted at this time makes us think that someone at higher rank, that is president Mustafa Kemal [Atatürk], personally intervened in the matter.” Atatürk was determined to modernize Turkey. By 1945 Turkey had saved over 190 intellectuals. Initially, the majority were saved from Germany, then from Austria after its 1938 takeover by Germany, and again from Czechoslovakia after the 1939 Nazi invasion of Prague. Because of Turkey’s neutrality and influence at least one needed professional, dentistry professor Alfred Kantorowicz,[[1]] was liberated from a nine month incarceration in a concentration camp and allowed to proceed with his family to Istanbul.

There is little doubt that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey's founder and first president, was personally involved with the emigre professors. Atatürk was in the midst of a major reform effort to modernize his new republic and saw this as an opportunity to encourage intellectual growth. Soon after the arrival of the first party he was known to have hosted a reception/banquet for them in the Dolmabahçe Palace . When the Shah of Iran visited Turkey for the first time, Atatürk personally arranged for Alfred Kantorowicz to create a set of dentures for him and for Ophtalmologist Joseph Igersheimer[3] to give the Shah an eye examination and prescribe new lenses.13. http://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Alfred_Kantorowicz

“What made Einstein the man of this century was not just his mind, it was also his soul”

Resources[edit]

- http://www.thewjc.org/sermons/einstein.htm Viewed September 3, 2007, Reisman, A. (2007) “Jewish Refugees from Nazism, Albert Einstein, and the Modernization of Higher Education in Turkey (1933-1945).” Aleph: Historical Studies in Science & Judaism, No. 7, Pages 253-281. http://inscribe.iupress.org/doi/abs/10.2979/ALE.2007.-.7. pgs 253-281

- Reisman, A. “German Jewish Intellectuals’ Diaspora in Turkey: (1933-1955).” The Historian. Volume 69 issue 3 Page 450-478, Fall 2007

- Reisman, A. (2007) “Harvard: Albert Einstein’s Disappointment.” History News Network. 01-22-07 http://hnn.us/articles/32682.html, “Einstein worked feverishly to rescue kin, friends, kin of friends and even strangers from the maw of Hitler’s Germany. He personally vouched for dozens, establishing in their names as many $2,000 bank accounts (required by immigration authorities) as he could afford. When tapped out, he beseeched friends and colleagues to put up funds, guaranteeing the deposits himself.” http://www.momentmag.com/Exclusive/2007/2007-04/200704-Einstein.html Viewed September 2, 2007

- There is some discrepancy as to who originally found this letter in the Foreign Ministry archives. For a discussion of that see, Reisman, A. (2006) What a Freshly Discovered Einstein Letter Says About Turkey Today, History News Network, 11-20-06, http://hnn.us/articles/31946.html

- This letter has been circulating within Turkey via the web for some time prior to its publication by the Hürriyet. This author received at least five e-mails from Turkish friends with the letter attached starting early October 2006.

“Teklifin mevzuatı kanuniyeyle telifi mümkün değildir.” “Bunları bugünkü şeriata göre kabule imkan yoktur.” Murat Bardakçı, “A REQUEST FROM THE GREAT GENIUS TO THE YOUNG REPUBLIC” Hürriyet, 29 October 2006. A banner first page headline article in a high-circulation broadsheet Turkish daily newspaper. The first group of invitees in 1933 numbered 30. It later grew to over 190 intellectuals and with families and staff the totaled over 1000 of saved individuals. For a complete listing of the individual intellectuals see Reisman, Turkey's Modernization: Refugees from Nazism and Atatürk's Vision. (Washington DC: New Academia Publishers, 2006) pp 474-478

- According to Istanbul University’s historian of science Prof. Feza Günergün (Cumhuriyet, Science and Technology Supplement, Nov. 3, 2006, Year: 20, Number: 10240) Einstein’s letter of September 17, 1933 was preceded by the July 6, 1933 agreement between the Turkish government and the “Notgemeinschaft” organization, (to be discussed later) at which time contracts for 30 German scientists had already been issued. Günergün suggested that by his letter “perhaps encouraged by this agreement Einstein made an attempt to send another 40 to Turkey.”

- Reisman, A. (2006) What a Freshly Discovered Einstein Letter Says About Turkey Today, History News Network, 11-20-06, http://hnn.us/articles/31946.html

The author thanks Ms Barbara Wolff of the Einstein Archives at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for her learned and helpful advice on this matter. Personal communication.

- Rifat Bali, a Turkish historian discovered this document in the Turkish State Archives during November 2006.

See A. Reisman, Turkey's Modernization 190[2]. Some of the Emigres served as conduits of communication between colleagues, friends, and relatives left behind and others in the free world. It is a great fortune from a historical perspective that some of this correspondence was preserved for posterity. See Reisman, Arnold, German Jewish Intellectuals’ Diaspora in Turkey: (1933-1955). The Historian Vol. 69 no. 3 pages 450-478, Fall.

- Ibid 200

- Ibid 166

- <http://vonhippel.mrs.org/vonhippel/life/AvHMemoirs9.pdf> Viewed on October 7, 2005. A. Reisman, Turkey's Modernization 190

- Ibid 165,166, and 260

- Ibid 156, 157

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Einstein was not in Paris on the day the letter was written, but it is apparent that he was making the request in his capacity of Honorary President of the OSE.

- ↑ Einstein A, Letter to Ismet İnönü Prime Minister of Turkey, Archives of Turkey's Prime-Ministry Office, September 17, 1933.

- ↑ Namal, A. and Reisman, A. "JOSEPH IGERSHEIMER (1879-1965) A visionary ophthalmologist and his contributions before and after exile" Journal of Medical Biography, The Royal Society of Medicine Press. Volume 15 November (2007) pgs 227-234

KSF

KSF