Vesalius

From Citizendium - Reading time: 16 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 16 min

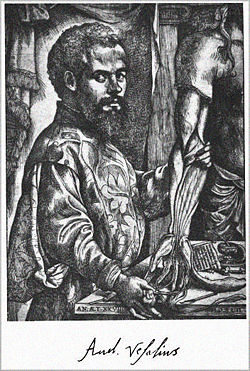

Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564), [2] [3] [4] [5] [Note 3] a Belgian (Flemish) Renaissance physician/surgeon, anatomist and physiologist, revolutionized the study and story of human anatomy and, as a consequence, the practice of medicine. He accomplished that feat (a) in virtue of the results of his dissections of human cadavers never previously performed and described with the factual accuracy of Vesalius's extraordinarily meticulous systematic detail and extensive documentation; (b) in virtue of the fluent writing [in Latin] of lucid descriptions of his anatomical and physiological findings precisely integrated with the accompanying illustrations; (c) in virtue of his gift for visualization and understanding of the importance of illustration for teaching anatomy, resulting in his having his anatomical findings exquisitely illustrated by his artist collaborators, including Jan Steven van Calcar and likely other pupils of the artist, Titian; and, (d) in virtue of his insistence on employing the findings of dissection of the human body as the arbiter of human anatomy, as opposed to accepting the reports of anatomists of antiquity.[Note 4] [6][Note 5] [7][Note 6]

Fabrica[edit]

In 1543, at the age of 28 years, Vesalius published De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Workings of the Human Body.) — generally referred to as the Fabrica — a work of many years of observations and illustrations of human dissections that not only laid the foundation for a realistic human anatomy but also demonstrated numerous errors in the anatomical assertions of the self-proclaimed heir of Hippocrates (460-360 BCE), Galen (129-216 CE) of Pergamum, the Greek physician/surgeon who based his description of human anatomy on extrapolations of dissections of animals and observations of the wounds of gladiators in Rome and Pergamum. Vesalius's contemporaries, having unquestionably accepted Galen's conclusions about human anatomy, found themselves in turmoil, stunned and even outraged at what eventuated as one of the most important contributions to the evolution of biology and medicine.[8]

In his book on the evolution of medicine, Sir William Osler considered the Fabrica "....one of the great books of the world", asserting as follows:

|

The worth of a book, as of a man, must be judged by results, and, so judged, the "Fabrica" is one of the great books of the world, and would come in any century of volumes which embraced the richest harvest of the human mind. In medicine, it represents the full flower of the Renaissance. As a book it is a sumptuous tome—a worthy setting of his jewel—paper, type and illustration to match...the chef d'œuvre of any medical library. [9] |

The U.S. National Library of Medicine offers an online gray-scale reproduction of some forty pages of the Fabrica, prepared in such a way that the reader can turn the pages, pause on any page to zoom on any section, read explanatory commentaries, and print pages.[10]

Medicine's intertwining with science began when physicians finally realized that universalizing, all-explaining theories about human biology served only to foster the misinterpretation of observed phenomena. Until then, a conflict between what was actually experienced and what the grand conceptual scheme told a physician he should be experiencing was always resolved in favor of the latter.

|

The year that saw publication of the Fabrica, 1543, also saw publication of Nicholas Copernicus's (1473-1543) De revolutionibus orbium coelestium libri vi (Six Books Concerning the Revolutions of the Heavenly Orbs) — the two books published a week apart. A memorable year, and a memorable pair of scholars who jump-started two revolutions, one on interpretations of the structure and function of the human body, the other on interpretations of the structure and movements of the earth and the sun. Those revolutions challenged ancient wisdom that had dominated thinking in medicine and astronomy.[12] These new ideas represent an anno mirabile in the history of science.

Vesalius' observations challenged some misconceptions of Christendom about the human body, and provoked opposition. Even Vesalius' teacher Sylvius denounced him to Charles V as a monster of impiety.[13] During the Middle Ages there was a widely held belief known as the Apostles' Creed that the flesh of the body would be resurrected in the future,[Note 7] and some thought the nucleus of the resurrected body took the form of a bone, which Vesalius failed to discover.[14] Another disproved idea was the "missing rib" used to create Eve.[Note 8] Some speculate that the Fabrica was sent to Basel for publication, instead of a much more convenient and easily supervised publication in Venice, to avoid anticipated censorship (the Roman Inquisition was formed in 1543, the year the Fabrica was published).[15] However, O'Malley considers the reason unknown (p. 430).

Vesalius was forced to steal his "materials" from the gallows and from tombs to perform his work, because he was unable to obtain enough cadavers legally for dissection.[16] According to O'Malley:

|

Nor should we overlook Vesalius's own initiative in the procurement of cadavers — of course illegally — as he became more confident of his position. Yet even with such assistance as he received, he must always have suffered from a shortage of dissection material, especially when we recall that there were no satisfactory preservatives. (p. 113) |

Vesalius himself describes the illegal source of several of his cadavers in the Fabrica as translated by Richardson and Carman.[17]

The history of Western science recognizes Vesalius's century as a turning point in the progress of science, a significant transition period straddling medieval science and the scientific revolution of the 1600s. Historian C. B. Schmitt states that one of the major growth points for scientific studies during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries lay in developments within biological science.[18] While many contributed to that growth, and did so in what biologists would now assign to many different disciplines of biology, Vesalius remains a key contributor, in pedagogical and scientific method, in knowledge, and in influence.

Chronology of Vesalius's life[edit]

Vesalius entered the world in Brussels, Belgium, late on the last day of 1514 or early on the first day of 1515, the newest member of a wealthy family of many generations of physicians. His father served as apothecary — preparer and dispenser of medications — in the royal court (Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-1558)). Father's duties apparently forced leaving the upbringing of Vesalius and his two brothers and a sister to the mother. Vesalius had access to his family's library of books. As a child Vesalius often visited a nearby site (Gallows Hill) where the authorities left criminals hanging until they rotted. Vesalius thus could begin to teach himself aspects of human anatomy at an early age. He continued to satisfy his curiosity of anatomy with the dissection of small animals, concentrating on both structure and function at a macroscopic level — the microscope not invented until after Vesalius's death.

At age 15, Vesalius began studying at the University of Louvain, where he learned, between 1530 and 1533, the subjects of rhetoric, logic, philosophy, and Latin. The University of Louvain stressed the Latin of the ancient Romans and attempted to inculcate a high degree of literary skill in reading and writing.[19]

After Louvain, Vesalius moved to study at the most prestigious center of medical science at the time, the University of Paris, attending from 1533 to 1536. As little information has emerged of Vesalius's activities during those three years, his biographer, C. D. O'Malley,[2] offers an educated argument from information on the workings of medical education at that time there. Near concluding, he writes:

|

It would be incorrect to liken the Vesalius of Paris to the later author of the Fabrica, and it is important to remember that although Vesalius in Paris may have been extraordinarily inquisitive, and he had acquired unusual skill in the technique of dissection, his vision was still considerably clouded by Galenism if, indeed, he was not a completely devoted Galenist. [2] |

Subsequently Vesalius moved to Italy, to the central hub of Renaissance culture and learning, Padua, where at the University there he quickly earned his medical degree (1537) and soon after a professorship in anatomy. Vesalius received his medical degree on 5 December 1537, and the “following day Vesalius took over the chair of surgery and anatomy, although there appears to be no official document that records his appointment….the fact is found only in the document that records his reappointment in October 1539…[t]he only other possible explanations for his appointment are the impression he may have made during the few months in which he was a candidate for the degree, and the quality of his examination, plus the fact that the chair to which he was appointed was not at that time of great significance, as the list of his predecessors indicates. Whatever the reason, Vesalius was appointed professor of surgery to succeed Paolo Colombo of Cremona”.[2]

Following publication of Fabrica Vesalius resigned his chair in Padua and became the physician to the royal household of Emperor Charles V in Brussels. In 1555 Charles V abdicated and Vesalius entered the service of Charles' son Philip II, the new ruler of Spain, and moved to Madrid.

In the spring of 1564 Vesalius undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Apparently, upon his return he intended to resume his chair in Padua. The reasons for this trip are not documented, but among the possibilities the most likely is that he ran afoul of the significant opposition to his dissections, and the trip was a penance imposed by the Inquisition in place of a judicial penalty.[13] On his return journey from the Holy Land later that year, a storm forced Vesalius' ship to the Greek island of Zakinthos (Zante) in the Ionian Sea, where he died.

Timeline[edit]

The image at right shows the timeline of Vesalius's life in relation to that of William Harvey, who advanced physiology as Vesalius did anatomy, and Marcello Malpighi, who completed the circuit of Harvey's circulation of the blood by his discovery of the capillaries. Each segment of years is one century.

Vesalius's work[edit]

The Fabrica illustration of the human cortex. Top panel: Figure 2 of Book 7; Bottom panel: Figure 3 of Book 7.

Figure accompanying Table 2 in Book 2 of the Fabrica. An image in color can be found here.

Vesalius’ major work was the Fabrica, printed by Johannes Oporinus of Basel in 1543. The letter of instructions submitting this work to the printer is available in English translation.[20]

As samples of the Fabrica, two gray-tone versions of Fabrica illustrations are shown. The figure at left provides two of twelve figures from Book 7: The brain and organs of sense that display the human brain. Vesalius describes in his figure captions the procedures used to obtain these views, and provides detailed observations upon the brain's construction. The figure at right shows one of many depictions of human musculature in Book 2: Ligaments and muscles. Although not obvious in the figure at this size, tiny labels identify individual muscles and are elaborated upon in the table accompanying the figure. As the figures progress, layers of muscle are peeled away (flayed) to show structure at all levels.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art website says about the posed figures in the illustrations:[21] “In addition to demonstrating the physical structures of the body, they imply concern for more elusive aspects of the human condition.”

Nuland summarizes Vesalius and his work in the following outline, presented verbatim:[22]

- “A. Fabrica has been interpreted to mean not just "structure" but "workings." Vesalius was as interested in the functions of the human body as he was in the anatomy itself.

- B. Published in 1543, Fabrica gave the world its first accurate knowledge of anatomy and a method by which it could be studied.

- C. Vesalius provided directions by which anyone with appropriate instruments and access to cadavers could perform dissections.

- D. Vesalius's book began the process of debunking Galen,[23][Note 9] though this would take centuries.[Note 10]

- E. Although Vesalius's text brought about the change, the work of its artist, Jan van Calcar, a protege of Titian, is what is most commented on today.

- F. The story of this book and of Vesalius himself is also the story of a series of events representative of the Renaissance, including:

- 1. A return to interest in the human body

- 2. A return to Greek learning

- 1. A return to interest in the human body

- G. The rise of the universities, which were the focus of Renaissance thought.”

In regard to point D, the influence of Galen on the description of human anatomy before and during Vesalius's time cannot be underestimated:

|

Indeed, when the young Vesalius began his study of human anatomy, the authority of the ancient anatomist had grown so weighty that anatomists tended to explain away discrepancies between his descriptions and their own observations in terms of individual abnormalities or changes in the human body that had occurred since the time of Galen. For example, Jacobus Sylvius (1478-1555) defended Galen's description of the human sternum as made up of seven bones on the grounds that human beings in a more heroic age might have had more bones than their degenerate descendants.[12] |

|

In the practice of medicine, the Renaissance saw the classic medical scholars of antiquity deified and staunchly deemed infallible and irreproachable. Like the enchanting songs of the sirens, their authoritative voices were so deafening that even one’s eyes could be fooled into believing that they could see what was not truly there. [24] |

Point E seems a bit exaggerated, possibly undervaluing historical and other scholarly commentary.[25] The suggested involvement of Jan Steven van Calcar is supported by Guerra,[26] but is admittedly not iron clad. Guerra also points out the importance of the wood engraver and well-known publisher, Francesco Marcolini da Forlí.[27][28] O'Malley, in his exhaustive biography of Vesalius, devotes seven pages specifically to a consideration of the illustrator(s) of the Fabrica, interpreting the documentary evidence as providing no definitive conclusion as to who prepared the illustrations, and no evidence with certainty that Calcar participated.[Note 11] O'Malley suggests that some of the illustrations were prepared by Vesalius himself and others by students of the studio of Titian. In any case, the art work is extraordinary: to quote Nutton,

|

"...its artwork, the co-production of anatomist, artist, block-cutter and printer, solved at a stroke many of the difficulties involved in representing a three-dimensional object on the printed page." |

The universal assessment of Fabrica today is summarized as:

|

"The result is, without question, the finest medical book ever published and one of the most beautiful books of all time." |

Vesalius as Galen resurrected[edit]

According to historian, Andrew Cunningham, in his book, The Anatomical Renaissance,[30] Vesalius exceeded Galen, surpassed him, went far beyond him, not by pointing out the erroneous conclusions Galen made about human anatony—the consequence of Galen's dissections performed not on human corpses but on those of apes and other non-human animals, of necessity, because of the proscription dictated by custom and law—nor did Vesalius surpass Galen by upbraiding him or holding him up for disrespect as dissector or anatomist—rather, Vesalius revived Galen, continuing Galen's anatomical project, in a metaphorical sense, by a metamorphosis of himself into another Galen, an extension or reincarnation of Galen.

For some 200 years before Vesalius, medievalists dissected human corpses, dissections for the most part motivated to demonstrate and confirm the anatomy of Galen, regarded as the infallible, the supreme authority on human anatomy[[2] pp. 11-17] [[30] p. 118]. The lecturer read from the text of Galen from an elevated lectern removed from the corpse, a surgeon dissector cut to reveal the Galenic truths, and a demonstrator with a pointing device pointed to the Galenic revelations—the latter two individuals performing their contributions sometimes days after the lecture. None had thought to repeat Galen's work, to dissect meticulously the human body and accept the evidence of the very images presented to their eyes and the feelings informing their hands, as Galen had done with non-human bodies.[30] None, that is, until Vesalius, the "born dissector",[31][Note 12] came along and did just that, and so "taught the world to see a different Galenic body; and...taught anatomists, physicians and philosophers to adopt a new ambition with respect to the Ancients of anatomy".[30]

After receiving his doctor of medicine degree in Padua and taking up his teaching duties, Vesalius quickly grew impatient with the traditional ritual of performing 'anatomies', as the three-person lecturer-dissector demonstrator ritual described above was called. He himself lectured as he dissected, at the same time demonstrating the parts and their relationships, encouraging students to come to the corpse and see and feel for themselves, roughly sketching at the dissection table the findings for the students to view and copy, sometimes bringing to the sessions illustrations he had made from previous dissections. In revealing where the Galenic texts were incorrect, he was not castigating Galen, he was being Galen, doing what Galen could not do because Galen could not dissect the human body. He even followed the sequence of dissecting the body as Galen did, in contrast to the traditional sequence that the pre-Vesalian anatomists employed.[30] His ambition was "to redo the whole of Galen's anatomy, but on the human body, the body it was supposedly about. In order properly to be Galen, Vesalius had to do what had not been available to Galen to do".[30] Thus, the Fabrica.

References[edit]

|

Many citations here include blue links that open variously to full-text or to a publisher's description of the work. Links to Google books often offer an extensive preview of the text. |

- ↑ Cushing H. (1962) A Bio-Bibliography of Andreas Vesalius. 2nd ed. Hamden, CT: Archon Books.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 O'Malley CD (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ball JM. (1910) Andreas Vesalius: The Reformer of Anatomy. (Free Full-Text) St. Louis: Medical Science Press. (149 pages)

- ↑ Miranda EA. Andreas Vesalius: A Biography, Original written by: Richard S. Westfall (1924-1996), Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University. Published here as a courtesy of Clinical Anatomy Associates, Inc. The original document can be found at the Galileo Project of the Rice University. Comment: A detailed resume of Vesalius Life and Work in outline form.

- ↑ Lind LR (translator, preface, introduction), Asling CW (anatomical notes), Clendening L (forward). (1949) The Epitome of Andreas Vesalius. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 1169943845. Comment: This book epitomizes Vesalius’s longer signal book, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of the Human Body). The translator’s Introduction offers a brief biography of Vesalius on pp. xvii-xix in the Questia text.

- ↑ Hazard J. (1996). "Jan Stephan Van Calcar, a valuable and unrecognized collaborator of Vesalius". Hist Sci Med. 30 (4): pp. 471-80. [Article in French] PMID: 11625048

- ↑ Zimbler MS. (2001) Vesalius' Fabrica: The Marriage of Art and Anatomy. Arch Facial Plast Surg 3:220-221. PMID: 11625048

- ↑ The preface Andrew Vesalius's book, On the Fabric of the Human Body. | A glimpse into the philosophy of Andreas Vesalius at age 28 years. ~4,000 words.

- ↑ Osler, Sir William (1921). The Evolution of Modern Medicine: A Series of Lectures Delivered at Yale university at the Silliman Foundation, in April, 1913. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 154.

- ↑ Andreas Vesalius's De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of the Human Body). National Library of Medicine. A 'turn the pages' online reproduction of the book.

- ↑ Nuland, Sherwin B (September, 2001). "The great books (the uncertain art)". American Scholar 70 (2): pp.125-128. Fourth paragraph.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Magner LN (2002). “Andreas Vesalius on the fabric of the human body”, A History of the Life Sciences, Third Edition, Revised and Expanded, pp. 83 ff. ISBN 0824708245.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lewis Samuel Feuer (1963). The scientific intellectual: the psychological & sociological origins of modern science. Transaction Publishers, p. 178. ISBN 1560005718.

- ↑ See Vesalius' commentary on the location of this bone in Charles Donald O'Malley (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. University of California Press, p. 159. See also Vesalius' discussion of the soul quoted in Charles Donald O'Malley (1964). Andreas Vesalius of Brussels, 1514-1564. University of California Press, p. 178.

- ↑ Roger Kenneth French (1994). William Harvey's natural philosophy. Cambridge University Press, p. 33. ISBN 0521455359.

- ↑ Katherine Park (2006). Secrets of women: gender, generation and the origins of human dissection. Zone Books, pp.123, 215, 217. ISBN 1890951676. “In part, this infrequency [of public dissections] arose from the scarcity of appropriate cadavers – foreign criminals executed in winter.”

- ↑ Andreas Vesalius (2008). William Frank Richardson, John Burd Carman (eds.): On the Fabric of the Human Body, Vol. 4. Book V: The Organs of Nutrition and Generation, Translation of the Fabrica of 1543. Norman Publishing, p. 189. ISBN 0930405889.

- ↑ Schmitt, CB (1983). “Recent trends in the study of medieval and renaissance science”, Pietro Corsi, Paul Weindling, eds: Information sources in the history of science and medicine. London: Butterworth Scientific, pp. 221-240. ISBN 0408107642.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Nutton, Vivian. Introduction to Northwestern's Vesalius:. De humani corporis fabrica, (On the fabric of the human body.). Northwestern University Vesalius website. Comment: Nutton's 'Introduction' gives an extensive and erudite biography of Vesalius

- ↑ John Bertrand de Cusance Morant Saunders, Charles Donald O'Malley (1973). The illustrations from the works of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels: with annotations and translations, a discussion of the plates and their background, authorship and influence, and a biographical sketch of Vesalius, Volume 56, Plates reproduced from the Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis Icones anatomicae: Bremer Press (1934) and text from World Publishing 1950 ed. Courier Dover Publications, pp. 46-48. ISBN 0486209687.

- ↑ De humani corporis fabrica, 1555. Heilbrunn timeline of art history. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Nuland SB (2005). Lecture three: Vesalius and the renaissance of medicine. Doctors: The history of medicine revealed through biography (12 lectures, 30 minutes/lecture), Course No. 8128. The Teaching Company.

- ↑ Fulton JF (1950). Vesalius four centuries later: Medicine in the eighteenth century, Logan Clendening Lectures on the History and Philosophy of Medicine First Series. University of Kansas Press.

- ↑ Joffe SN. (2009) Andreas Vesalius The Making, The Madman, and the Myth (Kindle Locations 50-52). Persona Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- ↑ For example, this Google search limited to the years after 2005 turns up over 14,000 hits referring to Vesalius in new books, and this Google scholar search turns up 4500 hits on articles in professional and technical journals in the same time period.

- ↑ Francisco Guerra (January, 1969). "The identity of the artists involved in Vesalius's Fabrica 1543". Med. Hist. 13 (1): pp. 37-50.

- ↑ Georges Duplessis (1871). P. Sellier, engraver: The wonders of engraving. Fleet Street, London: Sampson Low, Son and Marston, p. 7.

- ↑ Jane A. Bernstein (1998). Music printing in Renaissance Venice: the Scotto Press, 1539-1572. Oxford University Press, p. 171. ISBN 0195102312.

- ↑ Chauncey D. Leake (February, 1930). "The lure of medical history; a note on the medical books of famous printers: Part II". California and Western Medicine 32 (2): pp. 106 ff.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Cunningham, A. (1997). “Vesalius: The revival of Galenic anatomy”, The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. London: Scolar Press, pp. 88 ff. ISBN 1859283381.

- ↑ Morley H. (1915) Anatomy in Long Clothes: An Essay on Andreas Vesalius. Chicago: Toby Rubovitz. | Google Book Full-Text.

Notes[edit]

|

|

- ↑

[See ref: O'Malley CD. (1964)]: O'Malley's 1964 biography of Vesalius is considered the definitive biography. Renowned historian of medicine, F. N. L. Poynter, stated of Dr. O'Malley's book: "What strikes me immediately on reading Professor O'Malley's monumental work is the coolness of its judgment, the absence of any kind of special pleading or even of that warmth of expression which comes from the biographer's identification with his subject. This almost Olympian detachment is rare indeed and not to be found in any of the outstanding examples of the biographer's art which readily spring to mind." (See F. N. L. POYNTER. 1964. Andreas Vesalius of Brussels — 1514-1564: A Brief Survey of Recent Work. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 1964 XIX(4):321-326. PMID 14215447.

- ↑

[See ref: Ball JM. (1910)]: A vignette about Vesalius from Ball: "Vesalius began his career as an author by issuing a paraphrase, or free translation, of the ninth book of the Almansor of the celebrated Rhazes [footnote]. This book, liber ad Almansorem, or work dedicated to the Caliph Al-Mansur, was written by a learned Arab physician who lived between the years 860-932. The Almansor consists of ten books and was designed by the author for a complete body or compendium of Physic....The ninth book, which Vesalius translated from the barbarous version into a readable form, was so highly prized in mediaeval times that it was read publicly in the schools and was commentated by learned professors for more than a hundred years. By this publication Vesalius furnished a valuable contribution to medical literature. The numerous marginal and interlinear notes, which he supplied, show his intimate acquaintance with classical literature as well as with materia med-ica. Vesalius emphasizes the fact that the book of Rhazes contains many remedies which were unknown to the Greeks. The value of his edition was increased by the presence of original drawings of the plants mentioned in the text."

- ↑

During Vesalius's lifetime: (1) Henry VIII assumed the throne of England (reign: 1509-1547); (2) Martin Luther set off the Protestant Revolution (1517); (3) first circumavigation of Earth (1520-1522); (4) Publication of Nicholas Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (1543); (5) Elisabeth I assumed throne of England (reign: 1558-1603); Michelangelo (1475-1564).

- ↑ The name Steven is variously rendered in English as Steven, Stephen, and Stephan.

- ↑

[See ref: Hazard J. (1996)]: English Abstract of Hazard's work: Numerous and legitimate homages have been paid to Andreas Vesalius, eminent personality of the medical Renaissance. At that time scientific anatomy was inseparable from artistic one. As soon as 1535, Vesalius then 21 years old taught in Padova and at the University of Venice, a town harbouring many artists. It has been suggested that he had obtained the collaboration of Titian himself, but this hypothesis has not been confirmed. In fact "Lives of the best painters, sculptors and architects" G. Vasari expresses his admiration for the prints drawn by Calcar: "the illustrations conceived by Vesalius for his Fabrica and drawn by the outstanding flemish painter Jan Stephan Calcar are of an excellent style". For Carel van Mander nicknamed the "Vasari of the ancient Netherlands", it is to Calcar we owe Vesalius' anatomical plates. The reasons which have led this Flemish born around 1510 in Kalkar, a small town of the Cleves dukedom, to settle in Venice are both general and personal. Pupil of Titian, Calcar was an excellent portrait-painter who assimilated so well his master's style that he was adopted by the Italians calling him Giovanni Calcar. This valuable collaborator of Vesalius and brilliant pupil of Titian went to Naples for unknown reasons and stayed there until his premature death around 1546.

- ↑

[See ref: Zimbler MS. (2001)]: Excerpt from Zimbler: The Renaissance also brought about the emergence of a new focus in the realm of art. Aesthetic theory now dictated that a work of art should be a faithful representation of nature. This assumption required artists to acquaint themselves with the structure and physical properties of natural phenomena. Art had gone scientific! By the 15th and 16th centuries, artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael turned with enthusiasm to the detailed study of the human body.

- ↑

"... there was a noise, and behold a shaking, and the bones came together, bone to his bone. And when I beheld, lo, the sinews and the flesh came up upon them, and the skin covered them above;..." Ezekiel 37:7-8 (King James version) Although taken today as allegorical, this passage was interpreted as a reference to literal resurrection.

- ↑

"And the rib, which the LORD God had taken from man, made he a woman, and brought her unto the man." Genesis 2:22 (King James version)

- ↑

[See ref: Fulton JF. (1950)]: Vesalius on Galen: Historian John F. Fulton quotes Vesalius as exclaiming: I acknowledge no authority save the witness of mine own eyes—I must have the liberty to compare the dicta of Galen with the observed facts of bodily structure.

- ↑

[See ref: Nuland SB (2005)]: Nuland writes: By exposing Galen's errors and adding many new findings, this book clarified the understanding of anatomy and function in ways never previously imagined and began to loosen the ancient icon's stifling hold on medical thought.

- ↑

[See ref: O'Malley CD. (1964), pages 124-130]: On p. 124: "...opinions on the subject of their draughtsman or draughtsmen have been on occasion accompanied by strong and even heated convictions." And later (on p. 127): "Concerning the identity of the artists there is almost no information."

- ↑

[See ref: Morley H. (1915)]: "We meet only occasionally with born poets and musicians. Vesalius had a native genius of a rarer kind-he was a born dissector. From the inspection of rats, moles, dogs, cats, monkeys, his mind rose, impatient of restraint, to a desire for a more exact knowledge than they or Galen gave of the anatomy of man." (page 17)

KSF

KSF