Wizard of Oz

From Citizendium - Reading time: 11 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 11 min

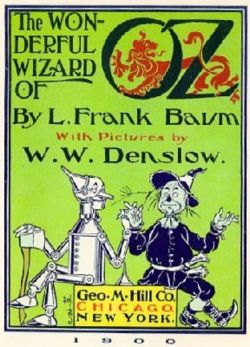

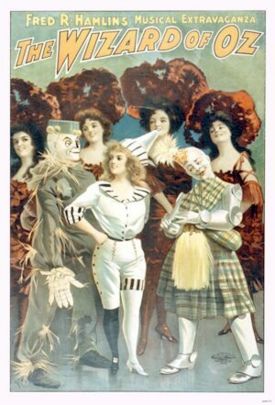

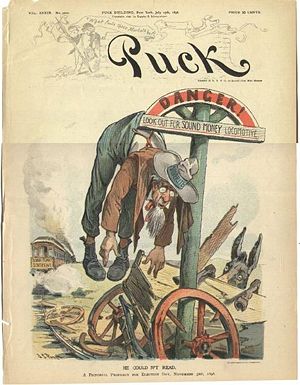

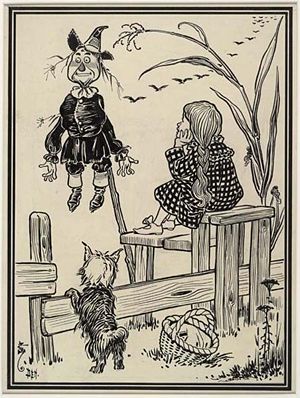

The Wizard of Oz is the title character of the American fantasy tales by L. Frank Baum (1856-1919), of which the most famous is the first (with W..W. Denslow (1856-1915)[1] as illustrator), The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The book was a runaway best seller, though the two coauthors became alienated, and both went bankrupt. Baum recouped by moving to Hollywood and writing a new series of Oz books; the series was continued after his death in 1919, with 40 Oz books in all. The first book became a smash Chicago hit musical in 1902 and moved to Broadway in 1903. Best known is the unusually successful Hollywood movie adaptation of 1939, starring Frank Morgan as the Wizard and Judy Garland as Dorothy. Political cartoonists used the Wizard image as early as 1906; in recent years Wizard themes appear in editorial cartoons on a weekly basis in the U.S.

Political interpretations[edit]

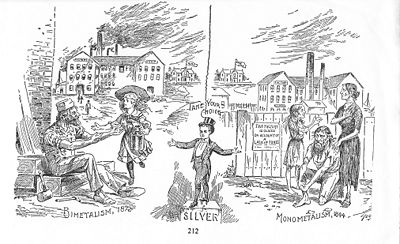

Historians and economists have interpreted the 1900 book (as well as the 1902 play and 1939 movie) as an allegory of the political, economic and social upheavals of America of the 1890s.

Both Baum and Denslow had been actively involved in politics in the 1890s. Baum edited a Republican newspaper in South Dakota; Denslow was an editorial cartoonist for a major Chicago daily.

Readers who grew up with the entire Oz series are often baffled by the political interpretation (for there is no politics in the continuation volumes), and deny that Baum intended any sort of modernized fairy tale. However, Baum explained in his introduction:

- The old time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as "historical" in the children's library; for the time has come for a series of newer "wonder tales" in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale. Modern education includes morality; therefore the modern child seeks only entertainment in its wonder tales and gladly dispenses with all disagreeable incident. Having this thought in mind, the story of 'The Wonderful Wizard of Oz' was written solely to please children of today. It aspires to being a modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heartaches and nightmares are left out.[2](

The musical comedy version of 1902-3 was a rewritten version for an adult audience, with many sexual innuendos and a very sexy Dorothy.

Sources[edit]

Baum and Denslow did not simply invent the Cowardly Lion, Tin Woodman, Scarecrow, gold-colored Yellow Brick Road, Silver Slippers, cyclone, flying monkeys, Emerald City, little people, Uncle Henry, witches and the wizard. The images and characters used by Baum and Denslow were based on the political images that were well known in the editorial cartoons of the 1890s. Baum and Denslow built a story around them, added Dorothy whose innocence and purity are more effective than the witches' magic. They added a series of lessons to the effect that everyone possesses the resources they need if only they had self-confidence. Positive thinking was a prevalent trend in this period, and Baum was involved with the Theosophy Movement that emphasized the power of pure thoughts over material evils. Baum's point is that evil is in the mind, and it takes positive thinking, not a political revolution, to destroy it.

Baum in the 1890s edited the major national magazine for advertising in store windows, and was familiar with the elaborate mechanical displays of the Christmas story that attracted tens of thousands of spectators to the display windows of Marshall Field's, Carson Pirie Scott, and other Chicago department stores.[3] The spellbinding mechanical ingenuity (based on intricate clockwork) led many viewers to believe there must be a man behind the screen who worked all the levers.

Many of the events and characters of the book resemble the actual political personalities, events and ideas of the 1890s. The 1902 stage adaptation mentioned, by name, President Theodore Roosevelt, oil magnate John D. Rockefeller, Senator Mark Hanna and other political celebrities. (No real people are mentioned by name in the 1900 book.) Even the title has been interpreted as alluding to a political reality: oz. is an abbreviation for ounce, a unit familiar to those who fought for a 16 to 1 ounce ratio of silver to gold in the name of Bimetallism[4]

Plot line[edit]

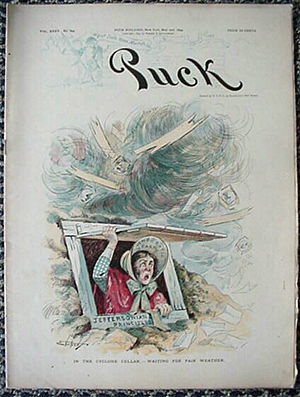

The book opens not in an imaginary far-off place but in real life Kansas, which in the 1890s was well-known for the hardships of rural life, and for destructive tornadoes (also called cyclones). The Panic of 1893 caused widespread distress in rural America. In 1896 and again in 1900 the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party had seized control and nominated the firebrand orator William Jennings Bryan, from Omaha, who crusaded across the land promising his panacea of "free silver" (whereby the government would turn cheap silver into real dollars farmers could use to pay their debts). His supporters truly believed it would transform America in a veritable utopia. Baum and Denslow, Republicans, rejected this notion and use the book to poke fun at Bryan (who is depicted as the Cowardly Lion).

The silverite revolution--a cyclone--sweeps away Dorothy and Toto to a colorful land of unlimited resources that nevertheless has serious political problems. This utopia is ruled in part by wicked witches. Dorothy's cyclone/revolution destroys the Wicked Witch of the East, slave-driver over the little people (Munchkins), who now celebrate their liberation. The Witch had controlled the powerful silver slippers (which were changed to ruby in the 1939 film).

The Good Witch of the North (the northern electorate) tries to help Dorothy, but she is not very smart, does not realize the power of the slippers, and sends Dorothy down the very dangerous gold road to the Wizard, who she mistakenly believes is so powerful that he can grant her wishes. (The northern vote elected McKinley in 1896 and he passed the gold standard into law.)

Along the Yellow Brick Road Dorothy picks up her coalition, the Scarecrow, Tin Woodman and Cowardly Lion, who all want the Wizard to grant their urgent wishes.

The national capital, the Emerald City, is a dream-like place based on the "White City," the common name for the Chicago World's fair of 1893, which Baum and Denslow attended often. The emerald green is an illusion (everyone must wear green glasses), symbolizing the fraudulent world of greenback paper money that only pretends to have value.

The Wizard/president is annoyed by his guests -- by the demands of the people. He is a corrupt politician, a shrewd manipulator who seeks power for himself, ignores the needs of the people, and rules by fooling with people's minds. He selfishly sends them to destroy his enemy, the Wicked Witch of the West. If she gets them, he is rid of a nuisance. If they kill her, great--he will be pleased and then worry what to do next.

The Wicked Witch of the West represents the trusts, who took control of small businessmen and made them cogs in their empire, just as the Witch does with the heroes, using the Flying Monkeys as her tools. The trust issue was in the headlines, with a popular solution--one actually used in 1911 against Standard Oil to dissolve them. Dorothy heaves a bucket of water and dissolves the Wicked Witch.

The heroes return to Oz to claim their reward, and expose the Wizard for a media-manipulating fraud. He has no real power and must leave Oz the way he came, on a hot air balloon. (Politicians were synonymous with metaphors like "hot air" and "full of gas.") But he is a shrewd psychologist, and realizes the heroes already possess what they think they lack, they just lack self confidence. He fills the Scarecrow's head with bran for a brain; implants a heart-shaped silk cushion inside the Tin Woodman (who now realizes his compassionate nature); he makes the Lion drink a dish of "courage" and he becomes king of the beasts again. He promises to take Dorothy back to Omaha, his hometown, but that plan misfires. The Good Witch of the South (the southern) vote appears. (In 1896 the South voted solidly for Bryan and free silver.) She is smarter than her sister the Good Witch of the North, and tells Dorothy to click her silver slippers three times--that believing will make it come true, and Dorothy arrives home again. It is a classic adventure story of travel to distant lands, and a story of running away from home and returning, a favorite theme for children.

Other allegorical devices[edit]

- Dorothy, naive, young and simple, represents the American people. She is Everyman, lost in a crazy utopia who wants to get back to normalcy and the love of her family. She resembles the young hero of Coin's financial school, a very popular silverite pamphlet of 1893. In her innocence and purity she is all powerful and personally kills two witches--she is Columbia, the symbol of the nation's conscience. Columbia was the usual representation of democracy in editorial cartoons (since replaced by the Statue of Libery.)

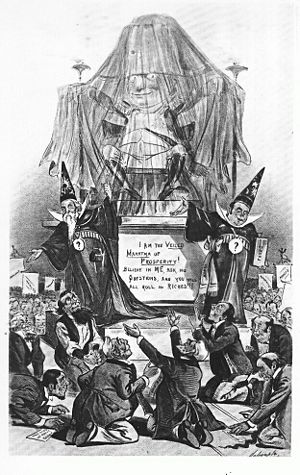

- The cyclone was used in the 1890s as a metaphor for a political revolution that would transform the drab country into a land of color and unlimited prosperity. The cyclone was used by editorial cartoonists of the 1890s to represent political upheaval.

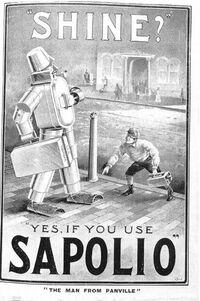

- The Tin Woodman was a stock symbol in cartoons and advertising. He was originally a human but was cursed by the Wicked Witch of the East so that every time he swung his axe he sliced off party of his body. As a good workman he replaced each part with tin, but now is all tin and has no heart. He is the worker dehumanized by industrialization, a common theme in Socialist literature of the day, such as expressed by Socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs in the 1900 election. The Woodman is rusted and helpless—ineffective until he starts to work together with the Scarecrow (the farmer), in a Farmer-Labor coalition that was much discussed in the 1890s, which culminated in the Farmer-Labor Party in Minnesota[5].

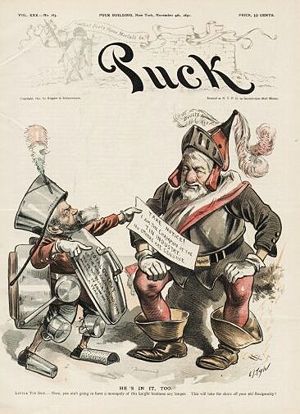

- The Munchkins are the little people—ordinary citizens. This 1897 Judge cartoon shows famous politicians as little people after they were on the losing side in the election.

Toto: Prohibitionist party (also called "Teetotalers")

Scarecrow: western farmers

Cowardly Lion: a cowardly politician, perhaps William Jennings Bryan

Wicked Witch of the East: Eastern factory owners and industrialists

Wicked Witch of the West: the trusts; one popular solution to the trust problem was to dissolve them, as Dorothy does.[6]

Flying Monkeys Pinkerton agents hired to break strikes

Wizard: President William McKinley

Oz: abbreviation for ounce of gold

Yellow Brick Road: gold standard

Cyclone: political revolution, the free silver movement

Emerald City: national capital

Silver Slippers: the free coinage of silver

Editorial cartoonists in recent decades have made heavy use of Oz imagery in political cartoons; the first to do so was W.A. Rogers whose 1906 cartoon ridiculed mud-slinging publisher William Randolph Hearst as the Wizard of Ooze"

Additional metaphors[edit]

- The Tin Man was a common feature in political cartoons and in advertisements in the 1890s. Indeed, he had been part of European folk art for 300 years.[7]

- The oil needed by the Tin Woodman had a political dimension at the time because Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company stood accused of being a monopoly (which was later ruled correct in a lawsuit brought by the federal government, and ultimately affirmed by the US Supreme Court.) In the 1902 stage adaptation the Tin Woodman wonders what he would do if he ran out of oil. "You wouldn't be as badly off as John D. Rockefeller," the Scarecrow responds, "He'd lose six thousand dollars a minute if that happened."[8]

- The lion that Dorothy, Scarecrow and Tin-Man encounter in the enchanted forest may be a reference to William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate for president in 1896. Cartoons often portrayed leading politicians as lions, and Bryan was described as having a great roar with no bite. People asked in early 1900, when the book was written, if he had the courage to oppose the McKinley Administration.

- In 1900 by far the most famous farmer in America was Henry Cantwell Wallace, editor of the leading farm magazine, Wallace's Farmer. Everyone called him "Uncle Henry."[9]

- "Aunt Em" is a puzzle. Baum's mother-in-law was named Matilda Joslyn Gage, and might be "Aunt M." Mary Lease the Populist spellbider has been suggested. ("Raise less corn and more hell!" was her shocking message, but Aunt Em is not like her.) Gage was a leader of the woman suffrage movement, but nothing about the book's character suggests suffrage interests.

- The poppies which surround the Emerald City are likely a reference to the opium poppies and the Boxer Rebellion in China of 1899.[10]

- Politicians of the era often talked about wizards. For example, one senator debating the gold and silver issue in early 1900 said, “We all know of the performances of the world’s magicians, but it has remained for the Wizard of Missouri [Senator Cockrell] to wave his magic wand or his magic head and double the price of the silver of the world.”[11] Baum may have turned the Wizard of Missouri into the Wizard of Oz, who frightened people with his giant magic head.

- President McKinley was often called a "wizard" for his political skills. The Wizard of Oz seems to be the president of the Land of Oz. The "man behind the curtain" echoes the response to automated store window displays.

- Dogs were often used in political cartoons to represent politicians or parties. Perhaps "Toto" is a play on the word "teetotaler", and represents the Prohibitionists of the era, who were aligned with Bryan in the 1896 election.

Adaptations[edit]

The Wizard inspired 40 official Oz books, 40 films, more than 100 unofficial novels, and innumerable websites, editorial cartoons, TV commercials, television shows, games, radio programs, video games, music videos, comic strips, musicals, toys, dolls, Japanese animes, ceramic firgurines, and even pornography, most of them based on the 1939 movie.[12] The copyright for the oiginal books published before 1923 has expired, but the 1939 film will be under copyright for decades to come.

The earliest musical version of the book was produced in Chicago in 1902, and moved to Broadway in 1903, where it was a smash hit and set a record with 293 performances. It used the same characters, but was aimed at adult audiences. Baum inserted current political references to the script. For example, his actors specifically mention President Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Mark Hanna, and John D. Rockefeller by name.[13]

The most famous adaptation is the 1939 film "The Wizard of Oz" featuring Judy Garland as Dorothy. Strong new political elements were added. The Wicked Witch of the West is played by the same actress who was the evil landowner in the opening scene who is trying to destroy Toto, while the Wizard is portrayed less as a humbug than as psychologically perceptive and helpful.

The Wiz was a Broadway hit musical with an all-black cast emphasizing the liberation from slavery. It was later made into a 1978 movie directed by Sidney Lumet, and starring Diana Ross as Dorothy and Michael Jackson as the Scarecrow. Gregory Maguire wrote Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West (1995). The 2003 Broadway musical "Wicked" (based on Maguire's novel) was a popular hit, with the Wizard's corruption emphasized. ==Impact on readers== The 40 Oz books had a significant impact on their young middle class readers who read them in English, Spanish, Russian, French, German, Romanian, Latin, Hebrew, or Arabic editions. Novelist Gore Vidal recalls:

- ""Like most Americans my age (with access to books) I spent a good deal of my youth in Baum's Land of Oz," he wrote. "I have a precise, tactile memory of the first Oz book that came into my hands. It was the original 1910 edition of The Emerald City of Oz. I still remember the look and the feel of those dark blue covers, the evocative smell of dust and old ink. I also remember that I could not stop reading and rereading the book. But 'reading' is not the right word. In some mysterious way, I was translating myself to Oz, a place which I was to inhabit for many years .... With The Emerald City, I became addicted to reading."[14]

Footnotes[edit]

- ↑ see Michael Patrick Hearn, "The Man Behind the Man Behind Oz: W. W. Denslow at 150," AIGA (July 05, 2006) at [1]

- ↑ . Apart from the contemporary political allusions, there is nothing "modern" (post 1800) in the novel. Quote from [[2]

- ↑ Culver (1988)

- ↑ Baum's son said he thought his father got the name from a file cabinet labeled A-N and O-Z.

- ↑ The party is now part of Minnesota's Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party

- ↑ Littlefield (1964), followed by others. saw her as the western draught which thus could be ended by water; Clanton (1991) suggests she represents the evils of left-wing Populism, or perhaps South Carolina' Pitchfork Ben Tillman,

- ↑ Archie Green, Tin Men (2002) excerpt and text search covers the history of images of tin men in European and American illustrations for 300 years.

- ↑ Swartz, Oz p 34

- ↑ Henry Wallace and Richard S. Kirkendall. Uncle Henry: A Documentary Profile of the First Henry Wallace (1993) excerpt and text search

- ↑ See the fascinating analysis by Martin Blythe, "Oz is China" (2006) online edition

- ↑ New York Times February 16, 1900 p 1

- ↑ Sherman, (2005)

- ↑ Swartz, Before the Rainbow, pp 34, 47, 56

- ↑ Quoted in , Nicholas Von Hoffman, "Flimflam Land. Civilization, Feb/Mar2000, Vol. 7, Issue 1

KSF

KSF