World War II, air war

From Citizendium - Reading time: 55 min

From Citizendium - Reading time: 55 min

During World War II, several countries including Great Britain, Germany, Japan and the United States were capable of fighting, and did carry out, air war.

Air Power and Germany[edit]

The German Air Force, or Luftwaffe, learned new combat techniques in the Spanish Civil War. Its high technology and rapid growth led to exaggerated fears in the 1930s that cowed the British and French into appeasement. In [[World War II, the Luftwaffe performed well in 1939-41, but was poorly coordinated with overall German strategy, and never ramped up to the size and scope needed in a total war. It never built large bombers, was deficient in radar, and could not deal with the faster, more agile P-51 Mustang pursuit planes after 1943. The Luftwaffe was narrowly defeated in the Battle of Britain (1940), and reached maximum size pf 1.9 million airmen in 1942. Grueling operations wasted it away on the eastern front after 1942. It lost most of its fighter planes to Mustangs in 1944 while trying to defend against massive American and British air raids. When its gasoline supply ran dry in 1944, it was reduced to anti-aircraft flak roles, and many of its men were sent to infantry units.

Air Power and Britain[edit]

Battle of Britain: 1940[edit]

- See also: Battle of Britain

Air superiority or supremacy was a prerequisite to Operation Sea Lion, the German amphibious invasion of Britain. German amphibious warfare tactics and capabilities were primitive, and the German Army and Navy believed an invasion could succeed only if the German Air Force could guarantee the Royal Navy would not be able to attack the landing force. To do so, the Royal Air Force had to be defeated.To achieve this, the Luftwaffe battled British air defense after the fall of France, from August to September 1940.

The Luftwaffe used 1300 medium bombers guarded by 900 fighters; they made 1500 sorties a day from bases in France, Belgium and Norway. The Germans immediately pulled out their Ju-87 Stukas, which were too vulnerable to modern fighters. The RAF had 650 fighters, with more coming out of the factories every day. Thanks to its new radar system, tightly coordinated with fighters, anti-aircraft artillery, and other defenses, the British knew where the Germans were, and could concentrate their counterattacks.

At first, and with the greatest danger to the British, Germans used their strategic bombing doctrine to focus on RAF airfields and radar stations. After the RAF bomber forces (quite separate from the fighter forces) attacked Berlin and other cities, Hitler swore revenge and diverted the Luftwaffe to attacks on London.

The success the Luftwaffe was having in rapidly wearing down the RAF was squandered, as the civilians being hit were far less critical than the airfields and radar stations that were now ignored. London was not a factory city and aircraft production went up.The last German daylight raid was September 30; the Luftwaffe was taking unacceptable losses and broke off the attack; occasional blitz raids hit London and other cities from time to time before May 1941, killing some 43,000 civilians. The Luftwaffe lost 1733 planes, the British, 915. The British showed more determination, better radar, and better ground control, while the Germans violated their own doctrine with wasted attacks on London.

The British surprised the Germans with their high quality airplanes; flying close to home bases where they could refuel, and using radar as part of an integrated air defense system (IADS), they had a significant advantage over German planes operating at long range. The Hawker Hurricane fighter plane played a vital role for the Royal Air Force (RAF) in winning the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940. A fast, heavily armed monoplane that went into service in 1937, the Hurricane was effective against both German fighters and bombers and accounted for 70-75% of German losses during the battle. The Battle of Britain showed the world that Hitler's vaunted war machine could be defeated.

Churchill's tribute to the Royal Air Force is eloquent:

Never, in the course of human events, have so many, owed so much, to so few.

.

Britain still faced starvation if the Battle of the Atlantic could not be won, and there was a long road ahead to defeating the Nazis and any possible invasion in the future.

Air Power and U.S.[edit]

The stunning success of the Luftwaffe's Stuka dive bombers in the blitzkriegs that shattered Poland in 1939 and France in 1940, proved to civilians that air power would dominate the battlefield, leaving the infantry far behind. The US Army was reluctant to draw that conclusion, but it was dumbfounded by the performance of the Stukas acting as a highly mobile, highly effective strike force--a super artillery. To defend against the Luftwaffe the Army decided to vastly expand the anti-aircraft units provided by the otherwise obsolete Coast Artillery branch. Airmen retorted the only solution was to build better planes that would shoot the Stukas down and gain control of the air. Airmen felt strongly that only they understood the enormous potential of air power, and that their vision was being held back. They dreamed of complete independence, noting that Germany's Luftwaffe and Britain's Royal Air Force (RAF) had long been disentangled from the old-fashioned, narrow-minded mud soldiers. The American people, enthusiastic about aviation in exact proportion to their fear of high-casualty trench warfare, and their love affair with modern technology, had long been supportive of a well-funded, independent air force. President Roosevelt sided with public opinion and the aviators. In 1940 he vowed to build 50,000 airplanes a year, far more than the most starry-eyed aviator had ever imagined. He gave command of the Navy to an aviator, Admiral Ernest King, with a mandate for an aviation-oriented war in the Pacific.[1] Roosevelt basically agreed with Robert Lovett, the civilian Assistant Secretary of War for Air, who argued, "While I don't go so far as to claim that air power alone will win the war, I do claim the war will not be won without it."[2]

Roosevelt rejected proposals for complete independence for the Air Corps, because the old-line generals and the entire Navy were vehemently opposed. In the compromise that was reached everyone understood that after the war the aviators would get their independence. Meanwhile, their status was upgraded from "Army Air Corps" to "Army Air Forces" (AAF) in June, 1941, and they seized almost complete freedom in terms of internal administration. Thus the AAF set up its own medical service independent of the Surgeon General, its own WAC units, and its own logistics system. It had full control over the design and procurement of airplanes and related electronic gear and ordnance. Its purchasing agents controlled 15% of the nation's Gross National Product. Together with naval aviation, it creamed the best young men in the nation. General Hap Arnold headed the AAF. One of the first military men to fly, and the youngest colonel in World War I, he selected for the most important combat commands men who were ten years younger than their Army counterparts, including Ira Eaker (b. 1896), Jimmy Doolittle (b. 1896), Hoyt Vandenberg (b. 1899), Elwood Queseda (b. 1904), and, youngest of them all, Curtis LeMay (b. 1906). Although a West Pointer himself, Arnold did not automatically turn to Academy men for top positions. Since he operated without theater commanders, Arnold could and did move his generals around, and speedily removed underachievers. Aware of the need for engineering expertise, he went outside the military and formed close liaisons with top engineers like rocket specialist Theodore von Karmen at Cal Tech. Arnold was given seats on the US Joint Chiefs of Staff and the US-British Combined Chiefs of Staff. Arnold, however, was officially Deputy Chief of [Army] Staff, so on committees he deferred to his boss, General Marshall. Thus Marshall made all the basic strategic decisions, which were worked out by his "War Plans Division" (WPD, later renamed the Operations Division). WPD's section leaders were infantrymen or engineers, with a handful of aviators in token positions. The AAF had its own planning division, whose advice was largely ignored by WPD. Airmen were also underrepresented in the planning divisions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and of the Combined Chiefs. Aviators were largely shut out of the decision-making and planning process because they lacked seniority in a highly rank-conscious system. The freeze intensified demands for independence, and fueled a spirit of "proving" the superiority of air power doctrine. Because of the young, pragmatic leadership at top, and the universal glamor accorded aviators, morale in the AAF was strikingly higher than anywhere else (except perhaps Navy aviation.)

The AAF provided extensive technical training, promoted officers and enlisted faster, provided comfortable barracks and good food, and was safe. The only dangerous jobs were voluntary ones as crew of fighters and bombers--or involuntary ones at jungle bases in the Southwest Pacific. Marshall, an infantryman uninterested in aviation before 1939, became a partial convert to air power and allowed the aviators more autonomy. He authorized vast spending on planes, and insisted that American forces had to have air supremacy before taking the offensive. However, he repeatedly overruled Arnold by agreeing with Roosevelt's requests in 1941-42 to send half of the new light bombers and fighters to the British and Soviets, thereby delaying the buildup of American air power. The Army's major theater commands were given to infantrymen Douglas MacArthur and Dwight D. Eisenhower. Neither had paid much attention to aviation before the war (though Ike learned to fly). By 1942 both had become air power enthusiasts, and built their strategies around the need for tactical air supremacy. MacArthur had been badly defeated in the Philippines in 1941-42 primarily because the Japanese controlled the sky. His planes were outnumbered and outclassed, his airfields shot up, his radar destroyed, his supply lines cut. His infantry never had a chance. MacArthur vowed never again. His island hopping campaign was based on the strategy of isolating Japanese strongholds while leaping past them. Each leap was determined by the range of his air force, and the first task on securing an objective was to build an airfield to prepare for the next leap.[3]

North Africa 1942-43[edit]

see also Operation Torch

Eisenhower's first command was the invasion of North Africa in November, 1942, at a time when the Luftwaffe was still strong. One of Ike's corps commanders, General Lloyd Fredendall, used his planes as a "combat air patrol" that circled endlessly over his front lines ready to defend against Luftwaffe attackers. Like most infantrymen, Fredendall assumed that all assets should be used to assist the ground forces. (More concerned with defense than attack, Fredendall was soon replaced by Patton.) Likewise the Luftwaffe made the mistake of dividing up its air assets, and failed to gain control of the air or to cut Allied supplies. The RAF in North Africa, under General Arthur Tedder, concentrated its air power and defeated the Luftwaffe. The RAF had an excellent training program (using bases in Canada), maintained very high aircrew morale, and inculcated a fighting spirit. Senior officers monitored battles by radar, and directed planes by radio to where they were most needed. The RAF's success convinced Eisenhower that its system maximized the effectiveness of tactical air power; Ike became a true believer. The point was that air power had to be consolidated at the highest level, and had to operate almost autonomously. Brigade, division and corps commanders lost control of air assets (except for a few unarmed little "grasshoppers," used to spot artillery; the AAF wanted no part of that subservient role.) With one airman in overall charge, air assets could be concentrated for maximum offensive capability, not frittered away in ineffective "penny packets." Eisenhower--a tanker in 1918 who had theorized on the best way to concentrate armor--recognized the analogy. Split up among infantry in supporting roles tanks were wasted; concentrated in a powerful force they could dictate the terms of battle.

The fundamental assumption of air power doctrine was that the air war was just as important as the ground war. Indeed, the main function of the sea and ground forces, insisted the air enthusiasts, was to seize forward air bases. Field Manual 100-20, issued in July 1943, became the airman's bible for the rest of the war, and taught the doctrine of equality of air and land warfare. The idea of combined arms operations (air, land, sea) strongly appealed to Eisenhower and MacArthur. Eisenhower invaded only after he was certain of air supremacy, and he made the establishment of forward air bases his first priority. MacArthur's leaps reflected the same doctrine. In each theater the senior ground command post had an attached air command post. Requests from the front lines went all the way to the top, where the air commander decided whether to act, when and how. This slowed down response time--it might take 48 hours to arrange a strike--and involved rejecting numerous requests from the infantry for a little help here, or a little intervention there.

Tactical Doctrine[edit]

Tactical air doctrine stated that the primary mission was to turn tactical superiority into complete air supremacy--to totally defeat the enemy air force and obtain control of its air space. This could be done directly through dogfights, and raids on airfields and radar stations, or indirectly by destroying aircraft factories and fuel supplies. Anti-aircraft artillery (called "ack-ack by the British, "flak" by the Germans, and "Archie" by the Yanks) could also play a role, but it was downgraded by most airmen. The Allies won air supremacy in the Pacific in 1943, and in Europe in 1944. That meant that Allied supplies and reinforcements would get through to the battlefront, but not the enemy's. It meant the Allies could concentrate their strike forces wherever they pleased, and overwhelm the enemy with a preponderance of firepower. This was the basic Allied strategy, and it worked. Air superiority depended on having the fastest, most maneuverable fighters, in sufficient quantity, based on well-supplied airfields, within range. The RAF demonstrated the importance of speed and maneuverability in the Battle of Britain (August, 1940), when its fast Spitfire fighters easily riddled the clumsy Stukas as they were pulling out of dives. The race to build the fastest fighter became one of the central themes of World War Two. The Japanese lost, because they never advanced beyond the Zero--a great plane in 1941, a loser in 1944.

Amazingly, the Germans "won" the technical race. In the critical year of the air war, 1944, they were flying the fastest, most maneuverable most heavily armed plane of the era, the Messerschmitt 262, the first jet. (The first British jet appeared a month later; the first US jet was ready in late 1945.) However, Hitler sent the ME-262 back to the drawing boards for reconfiguration as a bomber, and it never played a major role in the war. Hitler saw airplanes only as offensive weapons, and his interference prevented the Luftwaffe from acquiring and using enough fighter planes to stop the Allied bombers. By the fall of 1944, the Luftwaffe had virtually disappered. Hitler instead emphasized ant-aircraft defenses, such as the flak batteries that surrounded all major German cities and war plants, and which consumed a large fraction of all German munitions production in the last year of the war.[4]

Once total air supremacy in a theater was gained the second mission was interdiction of the flow of enemy supplies and reinforcements in a zone five to fifty miles behind the front. Whatever moved had to be exposed to air strikes, or else confined to moonless nights. (Radar was not good enough for nighttime tactical operations against ground targets.) A large fraction of tactical air power focused on this mission.

The third and lowest priority mission was "close air support" or direct assistance to ground units on the battlefront by blowing up bunkers, slicing through armor, and mowing down exposed infantry. Airmen disliked the mission because it subordinated the air war to the ground war; furthermore, slit trenches, camouflage, and flak guns usually reduced the effectiveness of close air support. "Operation Cobra" in July, 1944, targeted a critical strip of 3,000 acres of German strength that held up the breakthrough out of Normandy. General Omar Bradley, his ground forces stymied, placed his bets on air power. 1,500 heavies, 380 medium bombers and 550 fighter bombers dropped 4,000 tons of high explosives and napalm. Bradley was horrified when 77 planes bombed short: The ground belched, shook and spewed dirt to the sky. Scores of our troops were hit, their bodies flung from slit trenches. Doughboys were dazed and frightened....A bomb landed squarely on McNair in a slit trench and threw his body sixty feet and mangled it beyond recognition except for the three stars on his collar.[5] The Germans were stunned senseless, with tanks overturned, telephone wires severed, commanders missing, and a third of their combat troops killed or wounded. The defense line broke; Joe Collins rushed his VII Corps forward; the Germans retreated in a rout; the Battle of France was won; air power seemed invincible. However, the sight of a senior colleague killed by error was unnerving, and after Cobra Army generals were so reluctant to risk "friendly fire" casualties that they often passed over excellent attack opportunities. Infantrymen, on the other hand, were ecstatic about the effectiveness of close air support:

- Air strikes on the way; we watch from a top window as P-47s dip in and out of clouds through suddenly erupting strings of Christmas-tree lights [flak], before one speck turns over and drops toward earth in the damnest sight of the Second World War, the dive-bomber attack, the speck snarling, screaming, dropping faster than a stone until it's clearly doomed to smash into the earth, then, past the limits of belief, an impossible flattening beyond houses and trees, an upward arch that makes the eyes hurt, and, as the speck hurtles away, WHOOM, the earth erupts five hundred feet up in swirling black smoke. More specks snarl, dive, scream, two squadrons, eight of them, leaving congealing, combining, whirling pillars of black smoke, lifting trees, houses, vehicles, and, we devoutly hope, bits of Germans. We yell and pound each other's backs. Gods from the clouds; this is how you do it! You don't attack painfully across frozen plains, you simply drop in on the enemy and blow them out of existence.[6]

Two-way mobile radio equipment was not good enough for close air support until the last year of the war, when armored divisions assigned airmen to radio-equipped tanks to guide the attacks. In the first days of the Battle of the Bulge, in December 1944, bad weather grounded all planes. When the skies cleared, 52,000 AAF and 12,000 RAF sorties against German positions and supply lines immediately doomed Hitler's last offensive. Patton said the cooperation of XIX TAC Air Force was "the best example of the combined use of air and ground troops that I ever witnessed."[7] On the whole, however, ground forces grumbled endlessly that the AAF was not providing the "help" needed. Complaints escalated when it was noted that Marine Aviation had begun to provide close air support to Marines on the ground. The Army would never be satisfied, although in Vietnam they finally had ample close air support through their own helicopter gunships.

P-47 Thunderbolt[edit]

see P-47

To implement tactical air the United States needed better planes and pilots. The aircraft industry had lagged behind Germany, Britain and even Japan during the 1930s, so the nation entered the war with inferior equipment. At Guadalcanal, the Bell P-400 Aircobras were helpless against superior Japanese planes (consequently they were relegated to close air support, to the delight of the mud soldiers.) When Stalin asked for 500 additional Lend-Lease planes in 1942, he specified he did not want any more of the Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks, because it "was not up to the mark in the fight against modern German fighter planes." In a frantic technological race against the Nazis, American designers created a series of fighters and bombers that had the speed, climb-rate, maneuverability, and range to do the job.

The workhorse of tactical air power was the P-47 Thunderbolt. It originated in 1940, when Arnold asked for a plane to give air superiority over the Germans. Alexander Kartveli, chief designer at Republic Aviation, met the challenge using an unusually large fuselage and the new 18 cylinder, 2,000 horsepower air-cooled radial "Double Wasp" engine from Pratt and Whitney. Its high-altitude performance was dramatically enhanced by a General Electric turbo-supercharger.[8]

The 1945 version P-47M, burning 115/145 grade gasoline, had a maximum speed of 460 mph, a ceiling of 40,000 feet, and (with auxiliary drop tanks) a combat range of 2,000 miles. Escorting B-17s and B-29s, its 8 50-caliber machine guns could rip apart Luftwaffe or Japanese fighters (which had only 90 octane gasoline). As a tactical weapon it was armed with five 500 pound bombs plus ten 5" rockets. At ten tons, the big Thunderbolt needed a long runway, and was less agile than the Luftwaffe's Focke-Wolf 190. But it was better than good enough, downing 3 German planes for every loss.

Tactical Missions in Europe[edit]

As the Luftwaffe disintegrated in 1944, escorting became less necessary and fighters were increasingly assigned to tactical ground-attack missions, along with the medium bombers. To avoid the lethal fast-firing 20mm Oerlikon flak guns, pilots come in fast and low (under enemy radar), made a quick run, then disappeared before the gunners could respond. The main missions were to keep the Luftwaffe suppressed by shooting up airstrips, and to interdict the movement of munitions, oil and troops by blasting away at railway bridges and tunnels, oil tank farms, canal barges, trucks and moving trains. Occasionally a choice target was discovered through intelligence. ULTRA communications intelligence three days after D-Day pinpointed the location of Panzer Group West headquarters. A quick raid destroyed its radio gear and killed many key officers, ruining the Germans' ability to coordinate a panzer counterattack against the beachheads. In Europe after D-Day the Air Force averaged 1,300 light bomber crews and 4,500 fighter pilots. They claimed destruction of 86,000 railroad cars, 9,000 locomotives, 68,000 trucks, and 6,000 tanks and armored artillery pieces. Thunderbolts alone dropped 120,000 tons of bombs and thousands of tanks of napalm, fired 135 million bullets and 60,000 rockets, and claimed 3,916 enemy planes killed. Beyond the destruction itself, the appearance of unopposed Allied fighter-bombers ruined morale, as privates and generals alike dived for the ditches. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, for example, was seriously wounded in July, 1944, when he dared to ride around France in the daytime. The commander of the elite 2nd Panzer Division fulminated:[9]

- They have complete mastery of the air. They bomb and strafe every movement, even single vehicles and individuals. They reconnoiter our area constantly and direct their artillery fire....The feeling of helplessness against enemy aircraft has a paralyzing effect, and during the bombing barrage the effect on inexperienced troops is literally 'soul-shattering.'

Tactical issues in the Pacific[edit]

General George Kenney, in charge of tactical air power under MacArthur, never had enough planes, pilots or supplies. (He was not allowed any authority whatever over the Navy's carriers.) But the Japanese were always in worse shape--their equipment deteriorated rapidly because of poor airfields and incompetent maintenance. The Japanese had excellent planes and pilots in 1942, but ground commanders dictated their missions and ignored the need for air superiority before any other mission could be attempted. Theoretically, Japanese doctrine stressed the need to gain air superiority, but the infantry commanders repeatedly wasted air assets defending minor positions. When Arnold, echoing the official Army line, stated the Pacific was a "defensive" theater, Kenney retorted that the Japanese pilot was always on the offensive. "He attacks all the time and persists in acting that way. To defend against him you not only have to attack him but to beat him to the punch." Key to Kenney's strategy was the neutralization of bypassed strongpoints like Rabaul and Truk through repeated bombings. One obstacle was "the kids coming here from the States were green as grass. They were not getting enough gunnery, acrobatics, formation flying, or night flying." So he set up extensive retraining programs. The arrival of superior fighters, especially the twin-tailed P-38 Lightning, gave the Americans an edge in range and performance. Occasionally a ripe target appeared, as in the Battle of the Bismark Sea (March, 1943) when bombers sank a major convoy bringing troops and supplies to New Guinea. That success was no fluke. High-flying bombers almost never could hit moving ships. Kenney solved that weakness by teaching pilots the effective new tactic of flying in close to the water then pulling up and lobbing bombs that skipped across the water and into the target.[10]

Supplies were always short in the Southwest Pacific--one enterprising supply sergeant on Guadalcanal ordered engine gaskets from Sears, and thanks to the highly efficient mail service received them quicker than through regular channels. Kenney finally rationalized the supply system, but had no good solution to the lack of reinforcements. Airmen flew far more often in the Southwest Pacific than in Europe, and although rest time in Australia was scheduled, there was no fixed number of missions that would produce transfer back to the states. Coupled with the monotonous, hot, sickly environment, the result was bad morale that jaded veterans quickly passed along to newcomers. After a few months, epidemics of combat fatigue would drastically reduce the efficiency of units. The men who had been at jungle airfields longest, the flight surgeons reported, were in bad shape:

- Many have chronic dysentery or other disease, and almost all show chronic fatigue states. . . .They appear listless, unkempt, careless, and apathetic with almost masklike facial expression. Speech is slow, thought content is poor, they complain of chronic headaches, insomnia, memory defect, feel forgotten, worry about themselves, are afraid of new assignments, have no sense of responsibility, and are hopeless about the future. [11]

Marine Aviation: Reluctant Ground Support[edit]

The Marines had their own land-based aviation, built around the excellent Chance Vought F4U Corsair, an unusually big fighter-bomber. By 1944 10,000 Marine pilots operated 126 combat squadrons. Marine Aviation originally had the mission of close air support for ground troops, but it dropped that role in the 1920s and 1930s and became a junior component of naval aviation. The new mission was to protect the fleet from enemy air attacks. Marine pilots, like all aviators, fiercely believed in the prime importance of air superiority; they did not wish to be tied down to supporting ground troops. On the other hand, the ground Marines needed close air support because they lacked heavy firepower of their own. Mobility was a basic mission of Marine ground forces; they were too lightly armed to employ the sort of heavy artillery barrages and massed tank movements the Army used to clear the battlefield. The Japanese were so well dug in that Marines often needed air strikes on positions 300 to 1,500 yards ahead. In 1944, after considerable internal acrimony, Marine Aviation was forced to start helping out.

At Iwo Jima ex-pilots in the air liaison party (ALP), a predecessor of modern forward air control, not only requested air support, but actually directed it in tactical detail. The Marine formula increased responsiveness, reduced "friendly" casualties, and (flying weather permitting) substituted well for the missing armor and artillery.

For the next half century close air support would remain central to the mission of Marine Aviation, provoking eternal jealousy from the Army which was never allowed to operate fixed-wing fighters or bombers. ..The Army was allowed to have some unarmed transports and spotter planes. Beginning in 1965 (in Vietnam) heavily armed Army helicopter gunships were used to provide close air support.

Engineers Bulldoze New Airfields[edit]

Arnold correctly anticipated that he would have to build forward airfields in inhospitable places. Working closely with the Army Corps of Engineers, he created Aviation Engineer Battalions that by 1945 included 118,000 men. Runways, hangers, radar stations, power generators, barracks, gasoline storage tanks and ordnance dumps had to be built hurriedly on tiny coral islands, mud flats, featureless deserts, dense jungles, or exposed locations still under enemy artillery fire. The heavy construction gear had to be imported, along with the engineers, blueprints, steel-mesh landing mats, prefabricated hangars, aviation fuel, bombs and ammunition, and all necessary supplies. As soon as one project was finished the battalion would load up its gear and move forward to the next challenge, while headquarters inked in a new airfield on the maps. The engineers opened an entirely new airfield in North Africa every other day for seven straight months. Once when heavy rains along the coast reduced the capacity of old airfields, two companies of Airborne Engineers loaded miniaturized gear into 56 transports, flew a thousand miles to a dry Sahara location, started blasting away, and were ready for the first B-17 24 hours later. Often engineers had to repair and use a captured enemy airfield. The German fields were well-built all-weather operations; by contrast the Japanese installations were ramshackle affairs with poor siting, poor drainage, scant protection, and narrow, bumpy runways. Engineering was a low priority for the offense-minded Japanese, who chronically lacked adequate equipment and imagination.[12]

Strategic Bombing Doctrine[edit]

The airmen, while delighted with the greatly enhanced importance of air power implied by the emphasis on tactical air supremacy, in fact had a quite different doctrine regarding how air power could best be applied. It was "strategic bombing." Do not be misled by tanks and artillery and infantry, they insisted- -that was ancient history. The war could be won hundreds or thousands of miles behind the front lines--an invasion would be unnecessary because the bombers alone could defeat Germany and Japan. Modern warfare depended upon industrial production in large, fixed, visible factories, oil refineries and electric power stations. As Lovett explained, "Our main job is to carry the war to the country of the people fighting us--to make their working conditions as intolerable as possible, to destroy their plants, their sources of electric power, their communications system."[13] Strategic bombing was "guaranteed" to destroy those installations sooner or later. To win the war, therefore, it was necessary merely to build up a strategic air force from suitable bases. In Europe, the enemy was within attack range of B-17 bases in Britain and Italy. Matters were more complicated in the Pacific, where the Rising Sun flew above all the islands within range of Tokyo. Perhaps suitable bases could be built in China; a very-long-range bomber for those bases, the B-29, went into mass production. Closer and more secure bases could be built in the Mariana Islands (Saipan, Guam, Tinian), which therefore were invaded in June 1944.

In August, 1941, the AAF devised AWPD-1, its plan to win the war through air power alone (an appendix discussed tactical support for an invasion, should that prove necessary.) AWPD-1 read like an engineering document, and focused on the choke points of the German war economy. It listed 154 German targets in order of priority (electric power, railroad yards and bridges, synthetic oil plants, aircraft factories). By assuming half the bombs would land within 400 yards of their targets, it concluded that 3,800 bombers could finish the job in six months time. A total of 62,000 combat planes, and 37,000 trainers would have to be built. AWPD-42, completed a year later, provided more tactical air power, proposed a detailed strategic air war against Japan, and reaffirmed the same German targets (plus submarine yards). The summit conference at Casablanca in January, 1943, accepted the basic plan of AWPD-42: Germany and Japan would be the targets of massive strategic bombing that would either force their surrender or soften them up for an infantry invasion.[14]

Marshall and King did not fully accept the doctrine of strategic bombing. They insisted that control of the air would always be supplementary, and they much preferred tactical air. Furthermore, they denied that strategic bombing of the enemy's industrial strength would be decisive in warfare. Marshall accepted AWPD-1 as a blueprint for airplane acquisition and force levels (it proved astonishingly accurate), but refused to believe that strategic bombing could be decisive, noting "an almost invariable rule that only armies can win wars." Secretary of War Stimson, who usually backed Marshall 100%, disagreed this time: "I fear Marshall and his deputies are very much wedded to the theory that it is merely an auxiliary force." The debate between the AAF and the Army and Navy resulted in a compromise: both strategic and tactical air power would be used. The production of planes (AAF, Navy, Marines) was split about equally between strategic and tactical air, with 44% going to strategic bombers (especially the B-17 and B-29), 24% going to tactical ground-support and interdiction bombers (medium land-based Army and Marine, and and light carrier-based Navy planes), and 20% to fighters (which could either escort strategic bombers or be used as tactical air.) The remainder went for transports, trainers, and unarmed reconnaissance planes. Arnold kept to the compromise, and did provide Marshall with ample tactical air power, but with the proviso that his airmen would always decide on how, when and where it was to be used. In the boldest move for AAF autonomy, Arnold gained almost complete control over the strategic bombing campaigns against Japan and Germany. Nimitz and MacArthur, therefore, shared control of the Pacific war with Arnold in Washington, while Eisenhower shared control of the European war with Arnold. Secretary of War Stimson, however, trumped them all when he kept control of the atomic bomb in his own hands.

Goals and Achievements of Strategic Bombing[edit]

The American strategic bombing campaign against Germany was operated in parallel with RAF Bomber Command, which fervently believed in its own version of strategic bombing doctrine. The AAF bombed during the day, the RAF at night, when interception was difficult. Nightime navigation was so poor that the RAF quickly gave up precision bombing; their real target was the morale of the people who lived in the largest cities. According to Air Marshal Harris of RAF Bomber Command massive nightly raids would eventually burn out all the major German cities. The populace might survive in shelters, but they would be "dehoused", and lose confidence in the Fuehrer, which would lead to loss of German will to resist. Furthermore, the factories and railroad system would eventually be burned out as well. The British were willing to spend 30% of their GNP on Bomber Command, in order to weaken Germany, gain revenge, and avoid the high infantry casualties such as the Soviets were enduring.[15] Strategic bombing did "dehouse" 7.5 million Germans, but it hardly mattered, for the target cities had a surplus of housing (because most young men were away the army, most civilians had evacuated to the countryside, and all Jews sent to death camps and their apartments seized.) As the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported after the war, "Allied bombing widely and seriously depressed German morale, but depressed as discouraged workers were not necessarily unproductive workers." The German civilian air defense system enrolled 22 million volunteers, supervised by 75,000 full-time officials. Focusing on basement shelters in residential districts in the cities, the Germans built interconnected passageways, painted on fire retardants, and stored emergency supplies. The Gestapo, making tens of thousands of arrests, made certain that discontent was kept unfocused. Bombs did occasionally damage factories, but fast repairs were made. Rare indeed was the bomb dropped from 20,000 feet that destroyed a steel machine tool, especially when the bombadier had only the vaguest idea where it was or where he was.

Luftwaffe's Bombing Failure[edit]

The uses made of air power depend primarily on doctrine. This is clear from the failure of the Germans, Japanese and Soviets to build long-range strategic bombers. Germany had short- range bombers, but lacking a clear doctrine of how to use them it lost the "Battle of Britain" in late summer 1940. The Luftwaffe started by successfully attacking radar stations, command posts, airfields and fighter planes--a strategy that was on the verge of gaining complete and permanent air supremacy. Hitler, enraged when the RAF bombed Berlin, ordered the Luftwaffe to switch to bombing civilians (the "Blitz"). Thousands died but British morale never faltered. The RAF rebuilt its fighter strength and soon cleared British airspace of the Luftwaffe. The Luftwaffe could bomb and strafe, but was unprepared to defend itself against Spitfires and Hurricanes. Hitler's invasion of Britain required air superiority, so it had to be canceled. On the eastern front, Hitler expected the blitzkrieg to work so quickly that strategic bombing of Russian munitions factories would be unnecessary. By the time the Luftwaffe realized the necessity of hitting those factories, reverses on the ground put them out of range.

In the Mediterranean, the Luftwaffe tried to defeat the invasions of Sicily and Italy with tactical bombing. They failed because the Allied air forces systematically destroyed most of their air fields, and because by 1943 German pilots were so poorly trained that they could scarcely handle large planes. The Luftwaffe threw everything it had against the Salerno beachhead, but was outgunned ten to one, and then lost the vital airfields at Foggia.[16] After that it had only one success in Italy, a devastating raid on the American supply depot at Bari, in December, 1943. (Only 30 out of 100 bombers got through, but one found an ammunition ship.) The Germans ferociously opposed the American landing at Anzio in February, 1944, but the Luftwaffe was outnumbered 5 to 1 and so totally outclassed in equipment and skill that it inflicted little damage. Italian air space belonged to the Allies, and the Luftwaffe's strategic capability was zilch.

B-17 Flying Fortress as Strategic Weapon[edit]

see B-17

The centerpiece of America's strategic bombing was the B-17. Although originally designed in 1934, it was ahead of its time and proved a highly effective heavy bomber. A policy of continuous improvements added power gun turrets, bullet-proof glass, self-sealing fuel tanks, high-altitude oxygen systems, enlarged wing and tail surfaces, better radios, and ground- scanning radar. The power plant was upgraded with turbo- superchargers and 1,200 horsepower Wright Cyclone engines operating on 100 octane fuel (and later, 110/145 grade). The service ceiling rose to 35,000 feet, the range to 3,300 miles with a 4,000 pound payload. The AAF considered B-17 the perfect embodiment of its strategic bombing doctrine because of its long- range, its ability to defend itself, and its highly accurate Norden bombsight. The Norden allowed daylight precision bombing of specific targets like factories. It worked well enough in leisurely practice runs in sunny California at 10,000 feet with no flak or enemy planes. Over German airspace, in bad weather at 20,000 feet with shells exploding all around and enemy fighters a constant threat, the B-17 had at most 30 seconds over the target. "The flak is murder," the pilots said. "If you fly straight and level through it for more than ten seconds, you're a dead duck." Furthermore, it was hard to find the target in the first place. Navigation errors often put streams of 500 bombers many miles the wrong direction. At high altitude, with the usual cloud cover, it was nearly impossible to identify urban landmarks visually. On clear nights camouflage and dummy cities confused the navigators.[17] H2X, an American adaptation of the British radar system H2S, provided a crude mapping of the ground through cloud cover. It helped locate targets, but beginners' luck in its early trials gave planners a much exaggerated estimate of the accuracy the Flying Fortress could achieve. In late 1943, one bomber in 25 hit within one mile of the aiming point, and only one in 5 even got within five miles. If the aiming point was a factory or railroad yard, fewer than 10% of the bombs that did land there would do any real damage. Bombs that missed and landed in residential areas were just like the RAF's; they would destroy apartments, but the residents were usually safe in underground shelters. [18]

General Ira Eaker's Eighth Air Force first launched its heavy bombers against Hitler in August, 1942. The main priority until 1944 was the destruction of Luftwaffe planes in the air and on the ground. One year later, after 83 major missions aimed at France, Holland, and the German cities closest to the English Channel, Eaker sent 376 B-17s against the vital ball bearing factories at Schweinfurt and the Messerschmitt factory at Regensburg. Both small cities were located deep in Germany, far out of range of the P-47 and Spitfire fighters that normally escorted the bombers. German fighters and flak downed 60 bombers--a half dozen more raids like that and the 8th Air Force would cease to exist. After 30 more peripheral raids the Eighth tried Schweinfurt again in October, and again 60 Flying Fortresses (out of 320) were shot down. Accuracy was good despite the fierce resistance, and damage was heavy. The Germans took several months to rebuild (and to disperse critical plants so one raid would not prove fatal.) An effort to knock out the oil refineries at Ploesti, Rumania, which provided a third of Nazi oil, cost 54 out of 177 B-24 Liberators. However, the daring raid at very low level (100 to 300 feet) destroyed 40% of Ploesti's capacity. German repair crews made unexpectedly speedy repairs. The lessons were a profound blow to strategic bombing doctrines. Luftwaffe clearly had air superiority over the Nazi heartland, unescorted bombers would suffer unacceptably high losses, and even severe damage could be quickly repaired.[19]

In daylight, large formations of several hundred B-17s were easily spotted. For self-defense each Flying Fortress had 13 50- calibre machine guns, and flew in loose formations of 6 planes, each covering the others. In 1942-43 the Luftwaffe proved the Fortresses were vulnerable. Unexpectedly heavy German flak defenses disrupted formations, and damaged on average one-fourth of the bombers in each mission. Berlin was surrounded by an outer searchlight belt 60 miles in diameter, and a flak area 40 miles across. The searchlights helped the guns locate their targets and also blinded the navigators. Three massive 120-foot flak towers resembling medieval castles protected central Berlin with 8 128mm high velocity guns each. They fired a salvo every 90 seconds that created a killing window 260 yards across in the path of the bombers.

Hit by flak, some bombers crashed, while others fell out of formation; the stragglers were easy prey for fighters. The Luftwaffe moved fighters from the Eastern Front to the West. Improved German radar, new airfields, and centralized ground control allowed groups of fighters to be quickly vectored into the predicted flight path of the bombers. The fighters discovered the best way to attack was head-on ("Twelve O'Clock High!") because the very fast closing speed gave the B-17 gunners only a split second to aim, while the fighter pilot could aim his machine guns by pointing his entire aircraft at the bomber. The B-17 loss rate climbed from 3.5% per sortie in 1942 to 5% in early 1943. The B-17 was a robust plane able to withstand heavy punishment, but when 5% were lost in a single mission, the life expectancy per bomber was a mere 13 missions. The Luftwaffe was winning this war of attrition. New defensive techniques included forward-firing chin turrets, tighter formations of 18 planes, and deceptive diversionary attacks; they were not enough.

Destroying the Luftwaffe, 1944[edit]

In late 1943 the AAF suddenly realized the need to revise its basic doctrine: strategic bombing against a technologically sophisticated enemy like Germany was impossible without air supremacy. General Arnold replaced Ira Eaker with Carl Spaatz and Jimmy Doolittle, who fully appreciated the priority of air supremacy. They provided fighter escorts all the way into Germany and back, and cleverly used B-17s as bait for Luftwaffe planes, which the escorts then shot down.

Doolittle's slogan was "The First Duty of Eighth Air Force Fighters is to Destroy German Fighters.", one aspect of modern Offensive Counter-Air (OCA):

- Kill fighters in the air, often with deceptive maneuvers (see Operation BOLO for a Vietnam-era variant), RAF "Rhubarb" missions from low altitude and bad weather, and intruder missions where fighters would mingle with German fighters, vulnerable in taking off and landing

- Destroy fighters on the ground and disrupt airbases

- Stop fuel production and distribution

In one "Big Week" in February, 1944, American bombers protected by hundreds of fighters, flew 3,800 sorties dropping 10,000 tons of high explosives on the main German aircraft and ball-bearing factories. The US suffered 2,600 casualties, with a loss of 137 bombers and 21 fighters. Ball bearing production was unaffected, as Nazi munitions boss Albert Speer repaired the damage in a few weeks; he even managed to double aircraft production. Sensing the danger, Speer began dispersing production into numerous small, hidden factories.[20]

Paradoxically, the Luftwaffe would have to come out and attack or see its planes destroyed at the factory. Before getting at the bombers the Germans had to confront the more numerous, better armed and faster American fighters. The heavily armed BF-110 could kill a bomber, but it slowness made it easy prey for the speedy Thunderbolts and Mustangs armed with numerous fast-firing machine guns. The big, slow twin-engine Ju-88 was dangerous because it could stand further off and fire its rockets into the tight B-17 formations; but it too was hunted down. Germany's severe shortage of aviation fuel had sharply curtailed the training of new pilots, and most of the instructors had been sent into battle. Rookie pilots were rushed into combat after only 160 flying hours in training compared to 400 hours for the AAF, 360 for the RAF and 120 for the Japanese. They never had a chance against more numerous, better trained Americans flying superior planes.

The Germans began losing one thousand planes a month on the western front (and another 400 on the eastern front). Realizing that the best way to defeat the Luftwaffe was not to stick close to the bombers but to aggressively seek out the enemy, Doolittle told his Mustangs to "go hunting for Jerries. Flush them out in the air and beat them up on the ground on the way home." On one occasion German air controllers identified a large force of approaching B-17s, and sent all the Luftwaffe's 750 fighters to attack. The bogeys were all Mustangs, simulating B-17 flight patterns. Discovered too late, they shot down 98 interceptors while losing 11.

The actual B-17s were elsewhere, and completed their mission without a loss. In February, 1944, the Luftwaffe lost 33% of its frontline fighters and 18% of its pilots; the next month it lost 56% of its fighters and 22% of the pilots. April was just as bad, 43% and 20%, and May was worst of all, at 50% and 25%. German factories continued to produce many new planes, and inexperienced pilots did report for duty; but their life expectancy was down to a couple of combat sorties. Increasingly the Luftwaffe went into hiding; with losses down to 1% per mission, the American bombers now got through.[21]

By April, 1944, Luftwaffe tactical air power had vanished, and Eisenhower decided he could go ahead with the invasion of Normandy. He guaranteed the invaders that "if you see fighting aircraft over you, they will be ours." Indeed, on D-Day Allied aircraft flew 14,000 sorties, while the Luftwaffe managed a mere 260, mostly in defense of its own battered airfields. In the two weeks after D-Day, the Luftwaffe lost 600 of the 800 planes it kept in France.

From April through August, 1944, both the AAF's and the RAF's strategic bombers were placed under Eisenhower's direction, where they were used tactically to support the invasion. Airmen protested vigorously against this subordination of the air war to the land campaign, but Eisenhower forced the issue and used the bombers to simultaneously strangle Germany's supply system, burn out its oil refineries, and destroy its warplanes. Mission accomplished, Ike returned the bombers in September.[22]

V-1 and V-2: failure of German secret weapons[edit]

Hitler tried to sustain morale by promising that "secret weapons" would turn the war around. He did indeed have the weapons. The first of 9,300 V-1 flying bombs hit London in mid- June, 1944, and together with 1,300 V-2 rockets caused 8,000 civilian deaths and 23,000 injuries. Although they did not seriously undercut British morale or munitions production, they bothered the British government a great deal--Germany now had its own unanswered weapons system. Using proximity fuzes, British ack-ack gunners (many of them women) learned how to shoot down the 400 mph V-1s; nothing could stop the supersonic V-2s. The British government, in near panic, demanded that upwards of 40% of bomber sorties be targeted against the launch sites, and got its way in "Operation CROSSBOW." The attacks were futile, and the diversion represented a major success for Hitler. In early 1943 the strategic bombers were directed against U- boat pens, which were easy to reach and which represented a major strategic threat to Allied logistics. However, the pens were very solidly built--it took 7,000 flying hours to destroy one sub there, about the same effort that it took to destroy one-third of Cologne. The antisubmarine campaign thus was a victory for Hitler.[23]

Every raid against a V-1 or V-2 launch site was one less raid against the Third Reich. On the whole, however, the secret weapons were still another case of too little too late. The Luftwaffe ran the V-1 program, which used a jet engine, but it diverted scarce engineering talent and manufacturing capacity that were urgently needed to improve German radar, air defense, and jet fighters. The German Army ran the V-2 program. The rockets were a technological triumph, and bothered the British leadership even more than the V-1s. But they were so inaccurate they rarely could hit militarily significant targets.

Furthermore, the program used up scarce technical resources that could have gone into the development of air defense weapons like proximity fuzes and "Waterfall," a deadly ground-to-air rocket. The secret weapon of greatest threat to the Allies was the jet plane that could outfly Allied fighters and shoot down bombers. The Messerschmitt ME-262 prototype flew in 1939, but was never given high priority until too late. Hitler never understood air power; his personal interference repeatedly delayed the jets. First he proclaimed they would not be necessary, then insisted they be redesigned as bombers to make retaliation raids against London. The Luftwaffe would have been a much more deadly threat if it built ten thousand jets; it only made one thousand and they rarely flew combat missions.

Destroying Germany's Oil and Transportation[edit]

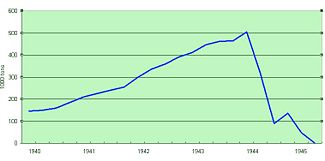

Besides knocking out the Luftwaffe, the second most striking achievement of the strategic bombing campaign was the destruction of the German oil supply. Oil was essential for U-boats and tanks, while very high quality aviation gasoline was essential for piston planes.[24] Germany had few wells, and depended on imports from Russia (before 1941) and Nazi ally Romania, and on synthetic oil plants that used chemical processes to turn coal into oil. Heedless of the risk of Allied bombing, the Germans had carelessly concentrated 80% of synthetic oil production in just 20 plants. These became a top priority for the AAF and RAF in 1944, and were targets for 210,000 tons of bombs. The oil plants were very hard to hit, but also hard to repair. As graph #1 shows, the bombings dried up the oil supply in the summer of 1944. An extreme oil emergency followed, which grew worse month by month.

The third notable achievement of the bombing campaign was the degradation of the German transportation system--its railroads and canals (there was little truck traffic.) In the two months before and after D-Day the American Liberators (B-24), Flying Fortresses and British Lancasters hammered away at the French railroad system. Underground Resistance fighters sabotaged some 350 locomotives and 15,000 freight cars every month. Critical bridges and tunnels were cut by bombing or sabotage. Berlin responded by sending in 60,000 German railway workers, but even they took two or three days to reopen a line after heavy raids on switching yards. The system deteriorated quickly, and it proved incapable of carrying reinforcements and supplies to oppose the Normandy invasion. To that extent the assignment of strategic bombers to the tactical job of interdiction was successful. When Bomber Command hit German cities, it inevitably hit some railroad yards. The AAF made railroad yards a high priority, and gave considerable attention as well to bridges, moving trains, ferries, and other choke points. The "transportation policy" of targeting the railroad system came in for intense debate among Allied strategists. It was argued that enemy had the densest and best operated railway system in the world, and one with a great deal of slack. The Nazis systematically looted rolling stock from conquered nations, so they always had plenty of locomotives and freight cars. Furthermore, most traffic was "civilian," and urgent troop train traffic would always get through. The critics exaggerated the resilience of the German system. As wave after wave of bombers blasted away, repairs took longer and longer. Delays became longer and more frustrating. Yes, the troop trains usually got through, but the "civilian" traffic that did not get through comprised food, uniforms, medical equipment, horses, fodder, tanks, fuel, howitzers, flak shells and machine guns for the front lines, and coal, steel, spare parts, subassemblies, and critical components for munitions factories. By January, 1945, the transportation system was cracking in dozens of places, and front-line units had more luck trying to capture Allied weapons than waiting for fresh supplies of their own.

Unanswered Weapons Systems[edit]

Germany and Japan were burned out and lost the war in large part because of strategic bombing. Targeting became somewhat more accurate in 1944, but the real solution to inaccurate bombs was more of them. The AAF dropped 3.5 million bombs (500,000 tons) against Japan, and 8 million (1.6 million tons) against Germany.

The RAF expended about the same tonnage against Germany; Navy and Marine bombs against Japan are not included, nor are the two atomic bombs. While it can be calculated that strategic bombing cost the US and Britain more money than it cost Germany, that calculation is irrelevant. The Allies had plenty of money. The cost of the US tactical and strategic air war against Germany was 18,400 planes lost in combat, 51,000 dead, 30,000 POWs, and 13,000 wounded. Against Japan, the AAF lost 4,500 planes, 16,000 dead, 6,000 POWs, and 5,000 wounded; Marine Aviation lost 1,600 killed, 1,100 wounded. Naval aviation lost several thousand dead.

One fourth of the German war economy was neutralized because of direct bomb damage, the resulting delays, shortages and roundabout solutions, and the spending on anti-aircraft, civil defense, repair, and removal of factories to safer locations. The raids were so large and so often repeated that in city after city the repair system broke down. In 1944 the bombing prevented the full mobilization of the German economic potential. Speer and his staff were brilliant in improvising solutions and work-arounds, but their challenge became more difficulty every week as one backup system after another broke down. By March, 1945, most of Germany's factories, railroads and telephones had stopped working; troops, tanks, trains and trucks were immobilized. With all their great cities crumbling into rubble, with the awareness the Allies had a weapons system they could not answer, Germans suddenly realized they were going to lose the war. In February, 1945, General Marshall overruled the ethical objections of Air Force commanders and ordered a terror attack on Berlin. It was designed to help the Soviet advance and to convince the Nazis their cause was hopeless; 2,900 died (both sides exaggerated the total to 25,000 for propaganda purposes.) Josef Goebbels, Hitler's bloodthirsty propaganda minister, was disconsolate when his beautiful ministry buildings were totally burned out: "The air war has now turned into a crazy orgy. We are totally defenseless against it. The Reich will gradually be turned into a complete desert." By July, 1945, Japan was almost totally shut down. The American and British airmen had achieved the goals of strategic bombing--but neither Berlin nor Tokyo would surrender. The Nazis quit when the Soviets smashed Berlin in the bloodiest battle of the war. The Japanese surrender will be considered later.

Strategic Bombing of Japan[edit]

Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall explained American strategy three weeks before Pearl Harbor:[25]

- "We are preparing for an offensive war against Japan, whereas the Japs believe we are preparing only to defend the Phillipines. ...We have 35 Flying Fortresses already there—the largest concentration anywhere in the world. Twenty more will be added next month, and 60 more in January....If war with the Japanese does come, we'll fight mercilessly. Flying fortresses will be dispatched immediately to set the paper cities of Japan on fire. There wont be any hesitation about bombing civilians—it will be all-out."

When war began the Philippine airbases were quickly lost. American strategy then focused on getting forwar airbases close enough to Japan to use the very-long-range B-29 bomber, then in development. At first the B-29's were stationed in China and made raids in 1944; the logistics made China an impossible base. Finally, in summer 1944, the U.S. won the Battle of the Philippine Sea and captured islands that were in range.

The flamability of Japan's large cities, and the concentration of munitions production there, made strategic bombing the war-winning weapon. Two months before Pearl Harbor Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek proposed sending Flying Fortresses over Tokyo and Osaka, "whose paper and bamboo houses would go up in smoke if subjected to bombing raids." Massive efforts (costing $4.5 billion dollars) to establish air bases in China failed. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese peasants broke rocks with little hammers and dug drainage ditches by hand. Shipping supplies around the world to equip the bases was almost impossible, and when some bases were ready in 1944 the Japanese Army simply moved overland and captured them. The Marianas, captured in June 1944, gave a close secure base, and the B-29 gave the Americans the weapon they needed. The B-29 represented the highest achievement of traditional (pre-jet) aeronautics. Its four 2,200 horsepower Wright R-3350 supercharged engines could lift four tons of bombs 3,500 miles at 33,000 feet (high above Japanese flak or fighters). Computerized fire-control mechanisms made its 13 guns exceptionally lethal against fighters. However, the systematic raids that began in June, 1944, were unsatisfactory, because the AAF had learned too much in Europe; it overemphasized self-defense. Arnold, in personal charge of the campaign (bypassing the theater commanders) brought in a new leader, brilliant, indefatigable, hard-charging General Curtis LeMay. In early 1945, LeMay ordered a radical change in tactics: remove the machine guns and gunners, fly in low at night. (Much fuel was used to get to 30,000 feet; it could now be replaced with more bombs.) The Japanese radar, fighter, and anti-aircraft systems were so ineffective that they could not hit the bombers. Fires raged through the cities, and millions of civilians fled to the mountains. Tokyo was hit repeatedly, and suffered a fire storm in March that killed 83,000. On June 5, 51,000 buildings in four miles of Kobe were burned out by 473 B-29s; Japanese opposition was fierce, as 11 B-29s went down and 176 were damaged. Osaka, where one-sixth of the Empire's munitions were made, was hit by 1,733 tons of incendiaries dropped by 247 B-29s. A firestorm burned out 8.1 square miles, including 135,000 houses; 4,000 died. The police reported: Although damage to big factories was slight, approximately one-fourth of some 4,000 lesser factories, which operated hand-in-hand with the big factories, were completely destroyed by fire.... Moreover, owing to the rising fear of air attacks, workers in general were reluctant to work in the factories, and the attendance fluctuated as much as 50 percent.

Japan's stocks of guns, shells, explosives, and other military supplies were thoroughly protected in dispersed or underground storage depots, and were not vulnerable to air attack. The bombing affected long-term factors of production. Physical damage to factories, plus decreases due to dispersal forced by the threat of further physical damage, reduced physical productive capacity by roughly the following percentages of pre-attack plant capacity: oil refineries, 83%; aircraft engine plants, 75%; air-frame plants, 60%; electronics and communication equipment plants, 70%; army ordnance plants, 30%; naval ordnance plants, 28%; merchant and naval shipyards, 15%; aluminum, 35%; steel, 15%; and chemicals, 10%.[26] Munitions output plummeted, and by July, 1945, Japan no longer had an industrial base. The problem was that it still had an Army, which was not based in the cities, and was largely undamaged by the raids. The Army had ammunition but was short of food and gasoline; as Iwo Jima and Okinawa proved, it was capable of ferocious resistance.

Why the Atomic Bomb?[edit]

Why did the US drop the atomic bomb? The decision was controversial at the time, with the decisionmakers knowing less than we do today, both on the effects of nuclear weapons, and on the internal Japanese arguments about conditions under which they would surrender. It has been suggested that the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey said the Japanese would have surrendered without the use of nuclear weapons, but the actual report emphasizes that opinion is made with the benefit of hindsight.[27]

With the benefit of hindsight, it appears that the twin objectives of surrender without invasion and reduction of Japan's capacity and will to resist an invasion, should the first not succeed, called for basically the same type of attack. Japan had been critically wounded by military defeats, destruction of the bulk of her merchant fleet, and almost complete blockade. The proper target, after an initial attack on aircraft engine plants, either to bring overwhelming pressure on her to surrender, or to reduce her capability of resisting invasion, was the basic economic and social fabric of the country. Disruption of her railroad and transportation system by daylight attacks, coupled with destruction of her cities by night and bad weather attacks, would have applied maximum pressure in support of either aim.

Some "revisionists" have suggested Hiroshima was supposed to be an unmistakable signal to Stalin to play along diplomatically with the Americans who planned to rule the postwar world. Many have asked whether some sort of demonstration explosion should have been made, in order to frighten Tokyo without killing so many people. The option was considered, but with only two bombs available Truman decided instead to drop millions of leaflets upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki warning people to leave immediately, and at the Potsdam Conference he explicitly warned Japan it must surrender immediately or be hit with terrible force.

The civilian government in Tokyo wanted peace on conditional terms, but that was impossible because of Roosevelt's policy of "unconditional" surrender, and because the civilians did not control Japan's decisions--the Army did (in the name of the Emperor.) It is often assumed that Hiroshima caused Japan to surrender. Perhaps; but simultaneously the Soviet Union declared war, invaded Manchuria, and crushed the Japanese army there. This ended Japan's feeble hopes for a negotiated peace and proved conclusively that the Army could no longer defend the nation. Even after Hiroshima and the invasion of Manchuria the Army and Navy wanted to fight on, while the civilians wanted to give up. The decisive move was the unprecedented intervention of Emperor Hirohito, who opened negotiations. With Roosevelt gone, the Americans redefined "unconditional" to allow continuance of the Emperor. Hirohito then broadcast an order to the nation and its armed forces to surrender, which was immediately obeyed.

The decision to use nuclear weapons[edit]

There was no consensus, among the small number of senior military leaders aware of the bomb development, about the separable issues of military effectiveness of such attacks, and the ethics thereof. While the casualties that would actually be caused by nuclear attacks were not known, the fire-bombing of Tokyo probably caused a greater number of casualties.

The first bomb to be used, a uranium fission device of the "gun" type code-named LITTLE BOY, had not been tested; only theoretical calculations of effect were available. Physicists involved in its development were certain it would work, but less so about the plutonium implosion technology in the second bomb. In the TRINITY test in New Mexico, an implosion device of the type used on Nagasaki was tested, and better data was available.

From the TRINITY experience, however, it was clear that a nuclear explosion would be qualitatively different than any previous attack, and would have great psychological impact. Nevertheless, there were both military commanders, and scientists that worked on the bombs' development, that preferred such measures as an initial demonstration, for the Japanese, on an uninhabited target. Other commanders and scientists believed that the shock value of the weapons would contribute to the ending of the war. Further complicating the situation was that the new President, Harry Truman, had not been informed of the bomb development while Vice President, and had a short time to make the decision.

The U.S., in anticipation of a possible nuclear attack, had bombed four cities, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki, less than other targets. This had two purposes: allowing better assessment of the weapon effects, and also having a greater shock value.

An argument against using these weapons was that Japan was clearly struggling under conventional bombings and the submarine blockade. Unfortunately, the U.S. had no sources inside the Japanese government, which would confirm that there was a stalemate between a hard-line faction that believed it appropriate to fight to the last Japanese, and a faction that was willing to examine a peace. The peace faction had come into being with the loss of Saipan and the resultant fall of the Tojo government, but the Allies had no hard information.

The primary argument was to use a radically different attack with the purpose of breaking the will of Japan, which actually was unlikely to affect the hard-liners. A secondary consideration was that the U.S. was planning a land invasion of Japan, with the first phase, Operation Olympic scheduled in October 1945, with the target of Kyūshū, which was under the command of Second General Army. That organization, comparable to an Allied army group, had its headquarters in Hiroshima Castle.

The U.S. Navy had very little to do with the atomic bomb decision. Having temporarily lost 5 of its 11 big carriers at Okinawa, it did not want to face the Kamikazes again during an invasion of Japan. It argued that the blockade was working well, cutting off nearly all oil, food and troop movements to and from Japan. It expected that the blockade would eventually lead to surrender. Civilians overruled them.

In July 1945 the AAF saw its doctrine of strategic bombing working as intended. The original plan was to have used B-29 bombers, from high altitude, with greater precision than the B-17 and B-24 bombers used in Europe. Unexpected high-altitude winds proved this was impossible, and Gen. Curtis LeMay, newly commanding the strategic bombers, on his own authority changed to low-altitude incendiary bombing. He shed the machine guns and gunners, and the gasoline no longer needed to lift the planes to 30,000 feet. The result was a doubling of the bomb load, and very scared fliers who were greatly relieved to discover their losses were less using the new tactics.[28] From the first raid on March 9, the new tactic was devastating. working to perfection. The B-29 dropping conventional high explosives and incendiaries was the perfect instrument to destroy the infrastructure of Japan's larger cities. The great bombing campaign had just started; it was planned to peak a year later. The atomic bomb was not part of AAF doctrine; the AAF generals had not been consulted, knew very little about the bomb and even demanded a direct order from President Truman before they agreed to explode it.

The Army agreed that the combination of blockade and strategic bombing would eventually destroy every Japanese city, but felt it could not destroy the Japanese Army, which was widely dispersed and dug in.

General Marshall worried that the American people might grow weary of more years of warfare, and might even demand some sort of compromise peace in order to bring the soldiers home. (Marshall underestimated the intense determination of nearly all Americans to destroy Japan.) Furthermore he objected to dropping the bombs on cities on moral and political grounds (Japan might become an enemy forever). Most of all, he had a tactical rather than strategic use in mind. Only a handful of bombs were being built, (two to four per month) and MacArthur's invasion forces ought to have all of them. Nine bombs had been allocated to "Operation Olympic". Marshall and his planners concluded that Japan would surrender only after ground troops captured Tokyo. The invasion of Kyushu was scheduled November 1; all bombs available then (probably seven) should be used there. They would give invading infantry forces enough firepower to destroy defensive ground installations, communications facilities, kill exposed enemy soldiers, and also block the arrival of reinforcements. To waste the precious bombs on irrelevant civilians would cause more American casualties, and like all the high American officials Marshall was committed to minimizing American--not Japanese-- losses.[29]

Manhattan Project[edit]

President Harry S. Truman, who had been completely frozen out of decision making and secret information before he suddenly became President in April, did not know what he wanted to do. He lurched this way then that, depending on who talked to him last.[30] The man who talked to him last about the bomb was Henry Stimson. Stimson rarely participated in strategic planning, but he had one card up his sleeve--the atomic bomb. To build it, Roosevelt, set up the Manhattan Project.

The Manhattan Project was managed by Major General Leslie Groves (Corps of Engineers) with a staff of reservists and many thousands of civilian scientists and engineers. Nominally Groves reported directly to Marshall, but in fact Stimson was in charge. Stimson secured the necessary money and approval from Roosevelt and from Congress, and made sure Manhattan had the highest priorities. He controlled all planning for the use of the bomb, overruling the high command of the Army, Navy and AAF in the process. He wanted "Little Boy" (the Hiroshima bomb) dropped within hours of its earliest possible availability. And it was. Stimson wanted Japan to surrender, and thought the Hiroshima bomb on August 6 would provide the final push Tokyo needed. When nothing seemed to happen he had Truman drop "Fat Man" on Nagasaki on August 9. The Japanese offered to surrender on August 10.[31]

Stimson's vision[edit]

In retrospect it seems likely that the impact of continued blockade, relentless bombing, and the Russian invasion of Manchuria would have somehow forced the Japanese Army to surrender sometime in late 1945 or early 1946 even without the atomic bombs (though not without very large numbers of Japanese casualties.)[32] But Stimson saw well beyond the immediate end of the war. He was the only top government official who tried to predict the meaning of the atomic age--he envisioned a new era in human affairs. For a half century he had worked to inject order, science, and moralism into matters of law, of state, and of diplomacy. His views had seemed outdated in the age of total warfare, but now he held what he called "the royal straight flush." The impact of the atom, he foresaw, would go far beyond military concerns to encompass diplomacy and world affairs, as well as business, economics and science. Above all, said Stimson, this "most terrible weapon ever known in human history" opened up "the opportunity to bring the world into a pattern in which the peace of the world and our civilization can be saved." That is, the very destructiveness of the new weaponry would shatter the ages-old belief that wars could be advantageous. It might now be possible to call a halt to the use of destruction as a ready solution to human conflicts. Indeed, society's new control over the most elemental forces of nature finally "caps the climax of the race between man's growing technical power for destructiveness and his psychological power of self-control and group control--his moral power."

In 1931, when Japan invaded Manchuria Stimson, then Secretary of State, proclaimed the famous "Stimson Doctrine." It said no fruits of illegal aggression would ever be recognized by the United States. Japan just laughed. Now the wheels of justice had turned and the "peace-loving" nations (as Stimson called them) had the chance to punish Japan's misdeeds in a manner that would warn aggressor nations never again to invade their neighbors. To validate the new moral order, the atomic bomb had to be used against civilians. Indeed, the Japanese people since 1945 have been intensely anti-militaristic, pointing with anguish to their experience at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Was Stimson then guilty of a crime (as many Japanese now believe)? Perhaps, but it has to be recognized that he moved the issue to a higher plane than one of military ethics. The question was not one of whether soldiers should use this weapon or not. Involved was the simple issue of ending a horrible war, and the more subtle and more important question of the possibility of genuine peace among nations. Stimson's decision involved the fate of mankind, and he posed the problem to the world in such clear and articulate fashion that there was near unanimous agreement mankind had to find a way so that atomic weapons would never be used again. Thanks in great part to Stimson's vision, they never have been used since August of 1945.[33]

Impact on Japan[edit]

The Strategic Bombing Survey did confirm that the weapons had a major psychological effect on the populace:

Prior to the dropping of the atomic bombs, the people of the two cities had fewer misgivings about the war than people in other cities and their morale held up after it better than might have been expected. Twenty-nine percent of the survivors interrogated indicated that after the atomic bomb was dropped they were convinced that victory for Japan was impossible. Twenty-four percent stated that because of the bomb they felt personally unable to carry on with the war. Some 40 percent testified to various degrees of defeatism. A greater number (24 percent) expressed themselves as being impressed with the power and scientific skill which underlay the discovery and production of the atomic bomb than expressed anger at its use (20 percent).[34]

Popular opinion was simply not of concern to the deadlocked Imperial Cabinet. Only the unprecedented intervention by the Emperor broke the tie in the direction of the peace faction. The U.S. accepted less than the unconditional surrender it had been demanding, not having known that the chief argument of the hard-liners was the continuation of the monarchy, the one condition on which the Japanese insisted.

Ethics debate on Strategic Bombing[edit]