Genghis Khan

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 3 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 3 min

| Genghis Khan | |

| |

1st Khan Emperor of the Mongol Empire

| |

| In office 1206 – August 18, 1227 | |

| Succeeded by | Ögedei Khan |

|---|---|

| Born | Temujin 1162[1] |

| Died | August 18, 1227 |

Genghis Khan (c. 1162 - August 18, 1227), or Chinngis Khan, was the first great military leader of the Mongols, a nomadic steppe people from Mongolia. He was born as Temujin, into the Kiyan clan of the Borjigin dynasty, the ruling family of the Mongol tribe.

The Mongol elite abandoned Temujin's family when he was nine, after the rival Tatar clan poisoned his father, who was one of the chiefs of the Kiyan. He along with his brothers gathered followers and allied with his father's ally, Ong Khan, the leader of the Kereyid tribe. In the 1190s he had enough support among the Borjigin clans that they elected him the fifth Khan of the Mongol, and he took the name Chingis (meaning "Oceanic"), which came through Persian to English as Genghis. Jamugha, a rival claimant to the Mongol leadership, then gathered the neighboring tribes of Mongolia, the Tatar, Kereyid, Naiman, and Merkid, into a series of wars against Genghis Khan. He conquered them one by one, and incorporated them into his army, until in 1206 he proclaimed the Yeke Mongol Ulus, or Great Mongol Nation, which history came to know as the Mongol Empire.[2]

Genghis came to believe that Heaven mandated him and his descendants to conquer the world. Starting in 1209, he conquered Western Xia, (a Tibetan kingdom in China), Black Cathay (a Central Asian kingdom), Jin Dynasty (a Chinese kingdom based in Beijing), Khwarezam (a Persian empire), and numerous peoples in Russia. Before he died in 1227, he arranged to have his empire divided among his three sons who still lived, and the two sons of his son that predeceased him. Genghis's descendants conquered the rest of China, Persia, and Russia, briefly creating the largest land empire that history had ever seen.

Genghis's Khan's Mongols were known for their brutality, but historians debate to what extent Mongol propaganda rather than fact is responsible for this. David Nicole wrote in his work The Mongol Warlords: "terror and mass extermination of anyone opposing them was a well-tested Mongol tactic." The alternative to unconditional surrender was total war. His battles with China were extensive, and he would reportedly count the number of enemy casualties by having his victorious soldiers each cut off an ear from the fallen and bring them back to him. Genghis based his powerful army on meritocracy. Historians consider Genghis Khan a military genius. Genghis' horse armies were able to travel further in a day than any other army until the development of automobiles.[3]

Genghis Khan was a tolerant leader in religious matters who did not influence religious practice by his subjects. All he demanded was total obedience in temporal matters. Those who did not obey faced stiff penalties, usually execution. Ultimately, the states that succeeded his empire withered and died largely as a result of the Mongols' failure to develop conquered economies, and failure to choose a religion upon which to base their state and society (and resulting overreliance on an arcane set of tribal customs).

Contents

Genghis Khan, Shamanism, religion and Christianity[edit]

Genghis Khan practiced Shamanism, but he believed that no one religion “guaranteed exclusive access to the right way”.[4]

With the exception of some policies affecting Jews and Muslims, Khan's empire largely had a policy of religious pluralism.[5] Khan called Muslims/Jews slaves and was offended by Jewish kosher eating practices and he forbade the Muslim halal method of butchering animals.[6] Jews were forbidden to practice circumcision and eating kosher. Muslims slaughtered sheep according to Islamic practices in secret under Khan's reign over them.[7]

Genghis Khan had six Mongolian wives and he established a large harem. Research indicates that he may have fathered thousands of children and it is theorized that 1 in 200 men alive today can trace their lineage to Genghis Khan.[8][9]

Khan had one Christian wife and according to Jack Weatherford's book Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, Khan “favored Christian spouses for his children and deliberately chose them because he thought they would make good parents for his grandchildren”.[10] Khan's children who married Nestorian Christian spouses practiced a syncretistic religious life and attempted to practice both Nestorian Christianity and Shamanism.[11]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

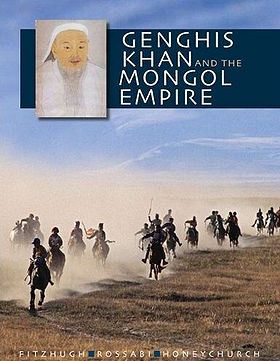

- Honeychurch, William, et al. eds. Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire (2009), essays by scholars

- Morgan, David. The Mongols (2007) excerpt and text search

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests (2001)excerpt and text search

References[edit]

- ↑ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Genghis-Khan

- ↑ Secret History of the Mongols, Paul Kahn, 1994

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Military History, Dupuy & Dupuy, 1979

- ↑ Did Genghis Khan Invent Religious Freedom?, The Gospel Coalition

- ↑ Did Genghis Khan Invent Religious Freedom?, The Gospel Coalition

- ↑ Johan Elverskog (2010). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road (illustrated ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-8122-4237-8.

- ↑ Michael Dillon (1999). China's Muslim Hui community: migration, settlement and sects. Richmond: Curzon Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-7007-1026-4.

- ↑ Genghis Khan: The daddy of all lovers, Daily Mail

- ↑ BBC Genghis Khan

- ↑ Did Genghis Khan Invent Religious Freedom?, The Gospel Coalition

- ↑ Mongol Empire and Religious Freedom, historyonthenet.com

KSF

KSF