Grover Cleveland

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 17 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 17 min

| Grover Cleveland | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 24th President of the United States From: March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1897[1] | |||

| Vice President | Adlai E. Stevenson | ||

| Predecessor | Benjamin Harrison | ||

| Successor | William McKinley | ||

| 22nd President of the United States From: March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1889[2] | |||

| Vice President | Thomas A. Hendricks (1885) | ||

| Predecessor | Chester A. Arthur | ||

| Successor | Benjamin Harrison | ||

| 28th Governor of New York From: January 1, 1883 – January 6, 1885 | |||

| Lieutenant | David B. Hill | ||

| Predecessor | Alonzo B. Cornell | ||

| Successor | David B. Hill | ||

| 34th Mayor of Buffalo, New York From: January 2, 1882 – November 20, 1882 | |||

| Predecessor | Alexander Brush | ||

| Successor | Marcus M. Drake | ||

| Former Sheriff of Erie County, New York From: 1871–1873 | |||

| Predecessor | Charles Darcy | ||

| Successor | John B. Weber | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Democratic | ||

| Spouse(s) | Frances Folsom | ||

| Religion | Presbyterian | ||

Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837 – June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th President of the United States of America, elected in 1884 and 1892. He was the representative conservative leader of the Gilded Age, and headed the Bourbon Democrats.

He was elected in 1884, defeated for reelection in 1888, then elected to a second term in 1892. Cleveland was the only Democrat elected president between James Buchanan in 1856 and Woodrow Wilson in 1912.

Cleveland was best known in his time for his honesty and courage, his leadership of the business-oriented Bourbon Democrats, and his opposition to the leftist forces that were overwhelming the Democratic party. In the 21st century, some conservatives praise his limited government values. Cleveland supported the gold standard and lower tariffs, and opposed imperialism, corruption, patronage, veterans' pensions, high taxes and silver-based inflation. Some historians point out that Cleveland was the last small government president the Democrats ever elected.[3] However, other historians argue that Cleveland began the steady expansion of the federal role.[4]

Cleveland's first term (1885–1889) was uneventful, but his second term (1893–97) was filled with economic crises and political upheavals. Cleveland was famous for breaking the Pullman Strike in 1894, which was paralyzing much of the national transportation grid west of Detroit. He was repudiated by his Democratic Party in 1896, as it nominated William Jennings Bryan in 1896, 1900 and 1908; Bryan lost each time. However the Democrats nominated Cleveland supporters Alton Parker in 1904 (he lost), and Woodrow Wilson in 1912 (he won).

Contents

Early career[edit]

Stephen Grover Cleveland was born in Caldwell, New Jersey on March 18, 1837; he had five brothers and four sisters. His father Richard Falley Cleveland was a Yale graduate and a Presbyterian clergyman, of Yankee descent. Cleveland's Puritan ancestors had moved to Massachusetts from England in 1635. Grover's mother, Ann Neal Cleveland, was the daughter of a Baltimore publisher. In 1841 the parents moved to Fayetteville, N.Y., and later to Clinton, N.Y., where Richard Cleveland died in 1853. Young Grover Cleveland was a mediocre student in high school; he never attended college. He worked for a time in a general store and then in an asylum for the blind. He moved to the growing lake city of Buffalo, N.Y. clerked in a law office and after a few years of tutorials was admitted to the Buffalo bar in 1859. He was the chief support for his widowed mother, so when he was drafted during the Civil War he hired a substitute; it later proved a political embarrassment.

Entry into politics[edit]

Cleveland, a Democrat active in local affairs, in 1863 was appointed assistant district attorney of Erie County, N.Y., which included the city of Buffalo. In 1865 he lost the election for District Attorney and became a partner in a private law practice, earning an about $10,000 a year (triple the average for lawyers). In 1871 he was elected Erie County sheriff and established a reputation as an honest and capable public official. During his time as sheriff he earned the nickname "Buffalo Hangman",[5] since his job included executions. Among the more well known hangings were Patrick Morrissey and John Gaffney.[6][7][8]

In 1881, as the reform candidate for mayor of Buffalo, Cleveland was easily elected. He instituted numerous reforms, emphasizing efficiency and economy in his administration. Friends called him the "veto mayor" because of his repeated use of the veto power to slow the spending by the city council.

Elected governor of New York 1882[edit]

The Republican Party in New York state was disorganized and in bad odor after a series of scandals. The Democrats realized they needed a perfectly honest candidate to win, one without connections to big city machines in New York, Brooklyn, Buffalo or Albany. Cleveland fit the need and was elected by 193,000. At Albany, the state capital, he was attacked by machine politicians, especially those of Tammany Hall (the Democratic organization in New York City), for refusing to give out patronage jobs sought by local party leaders trying to reward their best workers. Cleveland cooperated with Republican leader Theodore Roosevelt to clean up state politics. In 1883 he vetoed the popular "Five Cent Bill," which required a fare reduction for users of Jay Gould's street railroad in New York City, arguing that it violated the company's contract with the state and unwisely undermined private investment in public infrastructure.

Cleveland enlarged the scope of state government signing legislation to create a bureau of labor statistics (sought by labor unions), form a commission to plan a park at Niagara Falls, reorganize the militia (later renamed the national guard), abolished the hiring-out of state prisoners to private companies, set up higher standards for milk purity, and place a discriminatory tax on oleomargarine, as demanded by dairy farmers.

Elected president 1884[edit]

Reform was the theme at the national level in 1884, and Cleveland, governor of the largest and closest state, won the Democratic nomination for president as a new face with a sterling reputation. "We love him most for the enemies he has made," exulted one delegate and his campaign manager David Manning ran a smooth operation, during which Cleveland gave no speeches. The GOP nominated long-time Congressional leader James G. Blaine for president. Blaine was an able legislator, but was surrounded by whiffs of scandal. A Republican faction calling itself "Mugwumps" broke with Blaine and supported Cleveland. Reporters described Cleveland as "a very stout, exceedingly well-groomed looking gentleman, of medium height, with a full florid face, ... a soldierly-looking gray moustache and a pair of gray-twinkling, friendly eyes."[9]

The election of 1884 saw an intensely fought very close contest that turned on the electoral vote of New York. Cleveland crusaded against the corruptions represented by long-time Washington insider James G. Blaine, the GOP candidate. Part of Blaine's problem centered around a suspicious letter which terminated with the words, "burn this letter." Blaine's detractors marched and chanted, "Burn, Burn, Burn this letter!" The discovery that Cleveland—a bachelor—was paying child support to Maria Crofts Halpin[10] gave the GOP a moralistic counter-issue of its own, and a chant, "Ma! Ma! Where’s my Pa?"[11]

Blaine had made inroads into the Irish Catholic vote, normally 90+% Democratic, but blundered when a Protestant minister introduced him and denounced the Democratic party as the party of "Rum, Romanism and Rebellion." That is, the Democrats were the party of saloons, Catholics and Confederates; Catholics resented the slur and Blaine should have immediately repudiated it but failed to do so. Blaine lost his gains among Catholics at the last minute, and lost some Republican support to a prohibitionist candidate. Election day was Tuesday, and Cleveland led with 48.5% of the popular vote, but the Republicans did not concede until Saturday, when they realized that Cleveland's narrow margin in New York state proved decisive. Cleveland won the national popular vote by only 29,000 votes. In a very close election any number of small, almost random factors could be seen as decisive. Victory gave Democrats a new response, "Gone to the White House! Ha Ha Ha!"

Marriage[edit]

Grover Cleveland in June 1886 married Frances Folsom Cleveland in the White House. This was the second time a president had married while in office. The Clevelands had three children while in office.

Actions as President[edit]

Cleveland built a strong cabinet of men loyal to him, including Thomas Bayard as secretary of state, Manning as secretary of the Treasury, and William C. Whitney as secretary of the navy.

Cleveland refused to replace efficient Republican office-holders, angering patronage hungry local Democratic leaders but gaining the admiration of reformers. To signal the end of the Civil War era, he appointed two southerners to the cabinet, and returned Confederate battle flags that had been captured during the war. Union veterans were angry at him, an anger that intensified when he energetically vetoed hundreds of private pension bills based on dubious wartime claims. He set a record that still stands, with 414 vetoes in his first term. He vetoed twice as many bills as all previous presidents combined. Most were minor matters, though he also vetoed a major bill to restrict immigration from China.

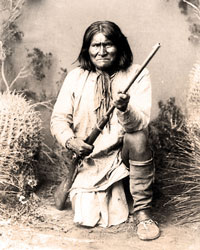

In 1886 Geronimo was captured by the Army, ending the Indian wars. In October 1886, Cleveland dedicated the Statue of Liberty, a project for which he asked some federal funding. In 1887 he signed the Interstate Commerce Act, passed unanimously by Congress in response to demands for some form of railroad regulation. The Act had little or no regulatory impact, but did tend to bury the issue.

Judicial appointments[edit]

In 1887 William B. Woods passed away, with Cleveland naming Lucius Q.C. Lamar II to replace him. The next year, he named conservative Chicago lawyer Melville Fuller as chief justice of the United States when Morrison Waite passed; Fuller served for twenty-two years.

Lowering the tariff[edit]

In 1887 Cleveland began to crusade against the high protective tariff, as an evil combination of corruption, inefficiency, and unnecessary taxation. "Unnecessary taxation," he explained, "is unjust taxation", harking back to the basic American hatred of taxation as a threat to individual liberty. He wanted a lower tariff "for revenue only" (it funded most of the federal government). Republicans, in alliance with industry, argued that a high tariff made for high wages, high profits, and faster economic expansion. Cleveland failed to lower the tariff in 1888 when the Mills Bill was defeated. In 1890 the Republicans raised rates again in the McKinley Tariff, which proved politically disastrous for the GOP.[12] Historians conclude that the tariff made a difference in the woolen industry (where Britain was a lower-cost provider), and possibly in steel, In other areas the U.S. was the worldwide low-cost produced and tariffs made little economic difference. American wages were higher, but efficiency was greater and so prices were lower.[13] The tariff was an important political issue because it symbolized the Republican dedication to rapid industrialization and GOP support from factory owners and factory workers.[14]

[edit]

The U.S. Navy was in deplorable condition by 1884, and Cleveland supported a systematic rebuilding of modern steel ships. The new warships proved highly effective against Spain in the war of 1898.

Expanding the federal government role in the economy[edit]

The Supreme Court's rejection (1886) of a state law regulating railroad rates convinced Cleveland that national controls for railroads engaged in interstate commerce were necessary. Congress agreed and in 1887 created the Interstate Commerce Commission; it was the federal government's first significant regulation of a major business sector. Cleveland approved the Hatch Act (1887), providing federal subsidies to state agricultural experiment stations. Congress upgraded the Department of Agriculture to departmental status (1889) and Cleveland supported its emerging role as a major research center for agricultural science.

Texas seed bill[edit]

In 1887, a severe drought was affecting the southern half of the United States, with Texas in particular being hardest hit. In response, Congress put together a relief bill for the farmers affected by the drought, with roughly $10,000 going for the purchase of seeds. When the bill got to his desk, Cleveland vetoed it.[15][16][17]

In his veto message, Cleveland explained his reasoning:

Though the people support the Government the Government should not support the people. The friendliness and charity of our countrymen can always be relied upon to relieve their fellow-citizens in misfortune. This has been repeatedly and quite lately demonstrated. Federal aid in such cases encourages the expectation of paternal care on the part of the Government and weakens the sturdiness of our national character, while it prevents the indulgence among our people of that kindly sentiment and conduct which strengthens the bonds of a common brotherhood.[18]

The result of this veto accomplished two important things. First, it protected the people from the malady of socialism and paternalism. Second, it firmly grounded the government on a Constitutional footing. As a result of the veto, charity from the American people rolled in, resulting in an amount in excess of over $100,000 dollars - more than 10 times the paltry sum Congress had appropriated. Historian Burton Folsom notes that "The Founders' view of charity, which was not always consistently applied, was vindicated by Cleveland's veto and the nation's generosity."[19]

1888 campaign[edit]

Cleveland and his Democrat running mate, Ohio white supremacist Allen G. Thurman, lost the 1888 Presidential Election to Republican Benjamin Harrison. Apart from endless discussions of the tariff, there were no major issues, as both parties rallied their armies of voters and the GOP did a slightly better job. Cleveland had chilly relations with intensely partisan Governor David B. Hill, leader of the Democratic Party in New York, and he narrowly lost the state and the election as Harrison won the Electoral College by a 204-197 margin. Cleveland nevertheless won the nationwide popular vote. Out of office, he moved to New York City, joining the prestigious Bangs, Stetson, Tracy and McVeigh law firm. Cleveland enjoyed a busy, lucrative practice, chiefly as a referee appointed by the courts.

1892 campaign[edit]

The Democrats won a landslide in the Congressional elections of 1890, attacking the McKinley Tariff, and the efforts of the GOP in Wisconsin and Illinois to shut down many religious schools. Cleveland easily defeated Harrison in 1892, and the Democrats took control of both houses of Congress.

Second term, 1893-97[edit]

Cleveland's most important appointees were John Carlisle as Secretary of the Treasury, and Richard Olney as Attorney General. Carlisle, of Kentucky, had been Speaker of the House, and was a tariff expert. Olney was a leading railroad lawyer in Boston; in 1895 the aggressive, undiplomatic Olney became Secretary of State. Cleveland had strained relations with the media, in sharp contrast to his successor McKinley who systematically used and manipulated the press to advance his political agenda.

Depression[edit]

Within weeks after Cleveland took office on March 4, 1893, the economy went into a tailspin. Every sector was hurt—farming, manufacturing, railroads, retail trade, and banking.

Silver and gold[edit]

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890 required the government to buy 4,500,000 ounces of silver each month, and to pay for it with the issue of new paper money. Conservatives denounced this as a wasteful subsidy to the silver miners and mine owners, and that it endangered the gold standard because there was not gold in the treasury to redeem all of the new government notes. Using all his powers of persuasion and patronage, Cleveland called a special session of Congress and forced the repeal of the law in October, 1893.[20] Nevertheless, the treasury continued to lose gold.

The depression continued to worsen, reaching a nadir in mid-1894. Prices, trade and profits continued to fall, and unemployment reached 20%. Some 156 railroads with 30,000 miles of track went bankrupt along with 800 banks and many small businesses.[21]

In 1895 the treasury's gold dupply had almost run out and Cleveland had to borrow gold from J. P. Morgan and the New York banks, an emergency move that embarrassed his administration and strengthened the silverites.[22]

Wilson Gorman tariff[edit]

Cleveland tried to lower the tariff in 1893-94 and result was a fiasco. The House did vote much lower rates, but protectionist Democrats in the Senate, led by Senator Arthur Pue Gorman, Democrat of Maryland, raised them again, and added an income tax of 2% on incomes over $4000, leaving Cleveland's main campaign promises of tariff reform in shambles. He allowed the "Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act", including the income tax, to become law without his signature in 1894.[23]

Pullman Strike: 1894[edit]

- For a more detailed treatment, see Pullman Strike.

Deep in the depression, in summer 1894 the Pullman strike, based in Chicago, was an attempt by workers tried to stop all trains, including those carrying the U.S. mail. Noting that the mail is a constitutional duty of the federal government, Cleveland rejected the demands by Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld, a fellow Democrat, to stay out. Altgeld, with ties to the labor unions, was a leader of the radical left wing of the party, and was using states rights arguments favored by southerners who wanted no federal protection of the voting rights of blacks. "If it takes the the entire army and navy ... to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered," he promised. Cleveland ignored Altgeld and the states rights argument—and indeed consulted with no one outside his cabinet—and sent in the army to take control of the rail yards in Chicago and dozens of other major cities. Cleveland had the strike leaders arrested as strikers attacked the army violently in numerous cities. The army reopened the rail system, ended the strike, and broke the union. Cleveland had made the most dramatic intervention of federal power into local affairs since the end of Reconstruction, and was bitterly resented by states-rights elements.

The fall elections of 1894 brought a massive Republican landslide, and wiped out the Populist party in the West and the Democratic party in the Northeast. The result was that Cleveland's leftist enemies in the Democratic party, based in the South and Midwest, ganied strength.

Hawaii[edit]

In 1893 Hawaiian businessmen overthrew the local queen, without bloodshed; they proclaimed an independent republic in 1894. They sought annexation to the U.S., which long had dominated the Hawaiian economy. Cleveland withdrew the treaty of annexation and sent his own agent James Henderson Blount to investigate. The Blount report said that support for the revolution by the American consul tainted its legitimacy. Cleveland was on the verge of sending the navy to conquer Hawaii and return it to the queen when she promised to behead all the revolutionaries. The notion that America would invade a peaceful republic and install a bloodthirsty absolute monarch so violated the principles of the American Revolution (when France aided the American rebels) that Cleveland sat silent. In 1898 Hawaii voluntarily joined the U.S.

Latin America[edit]

Cleveland wanted to enforce strict neutrality in the Cuban rebellion between 1895 and 1897, but American public opinion strongly supported the rebels. In 1898, under McKinley, the U.S. went to war to stop Spain's harsh suppression of the rebellion.

Cleveland took a bellicose stand against Britain in the Venezuela crisis of 1895, claiming the Monroe Doctrine gave him the right to intervene in a boundary dispute between independent Venezuela and British Guiana, a neighboring British colony. He stood behind Secretary of State Richard Olney's claim that the United States was "practically sovereign on this continent" and that its "fiat" was law. Britain ignored the hint of war and tried to maintain friendly relations with the U.S.; Britain and Venezuela resolved the issue through arbitration.

1896[edit]

Radical agrarians rejected Cleveland and the Gold Democrats, taking over the Democratic party in 1896 and nominating firebrand William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska. Bryan vehemently denounced industrialists and bankers in his famous “Cross of Gold Speech.” Bryan called for inflation by putting more money in circulation; his plan was to legislate cheap silver into legal currency at the ratio of 16 oz of silver to one oz of gold, hence the silverite slogan “16 to 1.” . Many of Cleveland's closest associates bolted the Democratic party and formed the "Gold Democrats"; many Cleveland supporters voted for republican candidate William McKinley. Cleveland himself remained silent.

Evaluation[edit]

Cleveland, the hardest worker in Washington, was a micromanager—answering the phone himself, drafting routine letters. He seldom consulted with other political leaders, and thus kept aloof from the wheeling and dealing and compromising that might undercut his reputation for total independence. The New York Times editorialized two days before he finally left office in March 1897, that this dutifulness "has completely estranged powerful Democrats who were able to deprive him of the support of great States and to turn against him their Members and Senators. It has provoked implacable enmities potent enough to obstruct or thwart his greatest designs and highest policies." Harry Thurston Peck, a shrewd journalist, concluded in 1908, "But it was Cleveland's lot to alienate in turn every important interest, faction and party in the United States; and he did this always in obedience to his own matured conception of his duty."

Historians are split. Many consider him among the greatest presidents because of his total commitment to honesty and civic duty. Indeed, all historians emphasize his courage, honesty opposition to corruption, and dedication to republicanism. The issue, however, is his impact on the nation, as critics praise his personality but downplay his achievements, noting that he left office repudiated by his party and the American people for his failures in the economic realm. Thus historian Thomas Bailey concluded, "He left office at the end of his second term with the economy panic riddled, the Treasury in the red, his party disrupted, his Republican opponents triumphant, and himself formally repudiated by his Democratic following."[24]

Retirement[edit]

Cleveland, nicknamed 'the Growler', retired to Princeton, New Jersey. Some people wanted him to run again in 1904, but he was too old. Sometimes President Theodore Roosevelt asked him for advice, but Cleveland refused to head Roosevelt's Coal Commission in 1893 because it meant selling his railroad stocks.

Cleveland died on June 24, 1908, from a heart and kidney disease, with his wife at his side. He is buried in the Princeton Cemetery.[25]

Honors and memorials[edit]

He will be on two dollar coins to be released in 2012 like every other president will, except one for each presidency.

Trivia[edit]

- The baseball player Grover Cleveland Alexander was named after him.

- Cleveland's grandson is a Presidential impersonator.

- Cleveland's granddaughter Philippa Foot is a retired UCLA and Oxford philosophy professor.

- Cleveland and Theodore Roosevelt were the only police officials to become president.

- Grover Cleveland's last words were "I have tried so hard to do right."[26]

- In 1893, on board the yacht Oneida, Cleveland had a malignant tumor removed from his mouth, presumably because he smoked heavily. Due to the Panic of 1893, the condition and operation was not revealed to the public.[27]

Bibliography[edit]

Biographies[edit]

- Blodgett, Geoffrey. "The Emergence of Grover Cleveland: a Fresh Appraisal" New York History 1992 73(2): 132–168. ISSN 0146-437X covers Cleveland to 1884

- Brodsky, Alyn. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Character (2000) - 496 pages; popular biography excerpt and text search

- DeSantis, Vincent P. "Grover Cleveland: Another Look." Hayes Historical Journal 1980 3(1-2): 41–50. Issn: 0364–5924, argues his energy, honesty, and devotion to duty - much more than his actual accomplishments established his claim to greatness.

- DeSantis, Vincent P. "Grover Cleveland," in William C. Spragens, ed. Popular Images of American Presidents (1988), ch 6 pp 131–46 online edition, highly favorable summary by leading historian

- Graff, Henry F. Grover Cleveland (2002), 155pp; short scholarly biography

- Jeffers, H. Paul. An Honest President: The Life and Presidencies of Grover Cleveland. 2000. 385 pp. popular, focused on personality

- McElroy, Robert. Grover Cleveland, the Man and the Statesman: An Authorized Biography (1923) old, but useful online edition v 1; online edition vole 2

- Markel, Rita J. Grover Cleveland (2006) 112pp; pre-high-school level excerpt and text search

- Merrill, Horace Samuel. Grover Cleveland and the Democratic Party (1957), short hostile biography by liberal scholar; generally hostile online edition

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (1932) Pulitzer Prize biography; very well written and thorough

- Whittle, James Lowry. Grover Cleveland (1896) 240 pages; old but fairly reliable study by British expert online edition

Specialized scholarly studies[edit]

- Bard, Mitchell. "Ideology and Depression Politics I: Grover Cleveland (1893-1897)" Presidential Studies Quarterly 1985 15(1): 77–88.

- Beito, David T., and Linda Royster Beito, "Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896-1900," Independent Review 4 (Spring 2000), 555–75. online edition, libertarian perspective

- Blake, Nelson M. "Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy." American Historical Review 1942 47(2): 259–277. in Jstor

- LaFeber, Walter/ "The Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy: A Reinterpretation," American Historical Review,’’ Vol. 66, No. 4 (Jul., 1961), pp. 947-967 in JSTOR, left-wing view

- Blodgett, Geoffrey. "Ethno-cultural Realities in Presidential Patronage: Grover Cleveland's Choices" New York History 2000 81(2): 189-210. ISSN 0146-437X; when a German American leader called for fewer appointments of Irish Americans, Cleveland instead appointed more Germans

- Campbell, Ballard C. The Growth of American Government: Governance From The Cleveland Era to the Present. (1995). 289 pp., argues that Cleveland began the steady expansion of federal role

- Dewey, Davis Rich. Financial History of the United States (1902) 530 pages online text

- Dewey, Davis R. National Problems: 1880-1897 (1907), survey of era online edition

- Doenecke, Justus. "Grover Cleveland and the Enforcement of the Civil Service Act," Hayes Historical Journal 1984 4(3): 44-58. ISSN 0364-5924, by conservative historian

- Faulkner, Harold U. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890-1900 (1959), scholarly survey of decade, online edition

- Ford, Henry Jones. The Cleveland Era: A Chronicle of the New Order in Politics (1921), short overview online

- Hirsch, Mark D. William C. Whitney, Modern Warwick (1948), good scholarly biography of close aide online edition

- Hoffman, Karen S. "'Going Public' in the Nineteenth Century: Grover Cleveland's Repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act" Rhetoric & Public Affairs 2002 5(1): 57-77. in Project Muse

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (1971), by a conservative historian

- Kelley, Robert. "Presbyterianism, Jacksonianism and Grover Cleveland." American Quarterly 1966 18(4): 615-636. Jstor, on Cleveland’s religion and its political implications

- Klinghard, Daniel P. "Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, and the Emergence of the President as Party Leader." Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 35, 2005 online edition

- McCarthy, G. Michael. "The Forest Reserve Controversy: Colorado under Cleveland and McKinley," Journal of Forest History, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Apr., 1976), pp. 80-90 in JSTOR

- Meador, Daniel J. "Lamar to the Court: Last Step to National Reunion" Supreme Court Historical Society Yearbook 1986: 27-47. ISSN 0362-5249

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969), thorough scholarly survey online edition

- Summers, Festus P. William L. Wilson and Tariff Reform, a Biography (1953) online edition, admires Cleveland

- Summers, Mark Wahlgren. Rum, Romanism & Rebellion: The Making of a President, 1884 (2000) campaign techniques and issues online edition

- Welch, Richard E. Jr. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988) standard scholarly overview of his two administrations

- Wilson, Woodrow, Mr. Cleveland as President Atlantic Monthly (March 1897): pp. 289-301 online Woodrow Wilson became President in 1912; he was a Cleveland supporter and this is a favorable essay.

Primary sources[edit]

- Grover Cleveland, The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland, edited by George Frederick Parker (1982) 571 pages online edition, coverage to 1892

- Grover Cleveland, Presidential problems (1904) memoirs, online edition from Questia; free online edition from Google

- President Cleveland Message about Hawaii December 18, 1893 - Cleveland's message where he tried to discredit the Hawaiian Revolution. It was contradicted by the Morgan Report issued by Congress in 1894.

- National Democratic Committee. Campaign Text-book of the National Democratic Party (1896) a fierce defense of Cleveland written by Gold Democrats who supported Cleveland and opposed Bryan and McKinley online from Google

- Nevins, Allan, ed. Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850-1908 (1934), major collection of his letters

- Parker, George Frederick. Recollections of Grover Cleveland, (1911) - 427 pages online edition

- Sturgis, Amy H. ed. Presidents from Hayes through McKinley, 1877-1901: Debating the Issues in Pro and Con Primary Documents (2003) online edition

- William L. Wilson; The Cabinet Diary of William L. Wilson, 1896-1897 1957

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.trivia-library.com/a/22nd-and-24th-us-president-grover-cleveland.htm

- ↑ http://www.trivia-library.com/a/22nd-and-24th-us-president-grover-cleveland.htm

- ↑ Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, "A Patriot's History of the United States" (2007)

- ↑ See Ballard C. Campbell, The Growth of American Government: Governance From The Cleveland Era to the Present. (1995) for the latter view.

- ↑ Which U.S. President Also Served As An Executioner?, Forbes

- ↑ THE EXECUTION OF JOHN GAFFNEY AT BUFFALO, NY 1873

- ↑ When Grover Cleveland Acted as Hangman, The New York Times

- ↑ New Outlook, Volume 129

- ↑ Summers, Rum, Romanism and Rebellion, p. 6

- ↑ President Cleveland’s Problem Child

- ↑ Several men could have been the father; Cleveland, the wealthiest, paid the child support perhaps was not the father.

- ↑ Tariff bills were usually named after the chief author, the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, and sometimes also the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.

- ↑ See Taussig, F. W. Some Aspects of the Tariff Question: An Examination of the Development of American Industries Under Protection (1931), and Taussig, The Tariff History of the United States. 5th edition 1910 online

- ↑ Irish Catholic textile mill workers were Democrats and opposed the tariff, but other factory workers voted republican and supported high tariffs.

- ↑ Grover Cared, National Review

- ↑ Why Grover Cleveland Vetoed the Texas Seed Bill

- ↑ Socialism for Texas Farmers

- ↑ Veto of Texas Seed Bill (February 16, 1887)

- ↑ New Deal Or Raw Deal?: How FDR's Economic Legacy Has Damaged America

- ↑ In the middle of the crisis he had secret emergency surgery to remove a cancerous growth in his mouth.

- ↑ Samuel Rezneck, "Unemployment, Unrest and Relief in the United States during the Depression of 1893-1897," Journal of Political Economy 61 (1953): 324-45 in JSTOR; Charles Hoffmann, "The Depression of the Nineties," Journal of Economic History 16 (1956): 137-64 in JSTOR

- ↑ Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (2001) online p. 73-74

- ↑ The Supreme Court in 1895 declared the income tax of 1894 unconstitutional. The income tax was legalized by the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913.

- ↑ Thomas Bailey, Presidential Greatness (1966) p 300

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Presidents by Zachary Kent, Chicago Press, 1988.

- ↑ Summers, ‘’Rum, Romanism and Rebellion,’’ p. 6

- ↑ Grover Cleveland's Rubber Jaw and Other Unusual, Unexpected, Unbelievable but All-True Facts About America's Presidents

External links[edit]

- Good scholarly essay on Cleveland with short essays on cabinet members and Mrs. Cleveland; from U of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Works by Grover Cleveland - text and free audio - LibriVox

| |||||

| ||||||||

KSF

KSF