Hamburger

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 4 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 4 min

A hamburger (or burger) is a sandwich that originated in Hamburg, Germany and is identified with America and the basis of a large fast food industry. There are many variations, but the typical burger comprises a bun containing a patty of ground, cooked beef. The burger is often typically served with some combination of relish, mustard, ketchup, cheese, lettuce, pickle and potato chips. The bun is usually toasted or warmed. It can be eaten with one hand while driving a car, though such can be dangerous due to being a potential choking hazard when applying the brake.

Contents

Variations[edit]

The hamburger is a convenience food or "fast food", often prepared for informal family and social events. Its meat can be grilled, fried, broiled, microwaved, or steamed. One of its most popular variations, a hamburger served with melted cheese on top, is called a cheeseburger.

Hamburgers are typically served on a bun and may come with a number of toppings and condiments:

Origins[edit]

The word "hamburger" refers to the German city of Hamburg, which once enjoyed prosperous commerce with the Baltic Provinces in Russia, where shredded raw meat (now called "steak tartare") was popular.[1] Around 1900, a popular meal in the United States was "Salisbury steak," cooked, ground steak, which was promoted by a food faddist named Dr. J. H. Salisbury as a cure for innumerable ailments.

Many cultures over the centuries have cooked finely chopped or ground meats in shapes such as meatballs, patties, or steaks, often flavored with other ingredients. The Larousse Gastronomique, for instance, gives a half-dozen Hungarian, German, and Austrian recipes for what it calls Keftedes, all translated as variations on "hamburgers".[2]

Standardized fast food[edit]

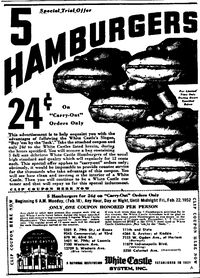

Tens of thousands of diners and restaurants in the U.S. serve their own version of the hamburger. Standardization was invented by Walter Anderson, who in 1916 in Wichita, Kansas, opened the first of a nationwide chain of White Castle fast food outlets. Anderson trained his staff to cook and serve in exactly the same way, cooking dozens of pre-weighed, pre-shaped burgers at once on a dedicated griddle, and serving them on specially designed buns; the customers paid 5 cents. Ray Kroc (1902-1984) in 1954 bought a California "drive-in burger bar" from Richard and Maurice McDonald. Kroc standardized his product, so that today the McDonalds hamburger has meat that weighs 1.6 ounces (45 grams) and measures 3 and 5/8 inches (9.2 cm) across; and is garnished with a quarter of an ounce of chopped onion, a teaspoon of mustard, a tablespoon of ketchup and a pickle slice one inch in diameter. The Big Mac is likewise standardized with two patties and a sauce. Customers have limited choices, but are typically served in less than 90 seconds. The local franchiser, who spent millions to buy the outlet, has little control over the menu, and must purchase supplies from the corporation, and pay it a royalty fee as a percent of sales.

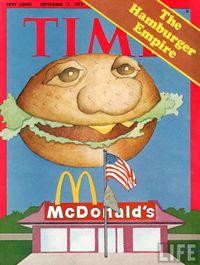

In the 1960s the McDonald's Corporation turned the burger into the Model T of fast food. The hamburger played an important role in America's transformation into a mobile, suburban culture, and in the 21st century. Despite strong competition from pizza and tacos, it remains America's favorite sandwich. By 1985 McDonald's was selling 5 billion burgers a year (and stopped updating the count on its distinctive yellow arches.) Over 31,000 McDonald outlets operate in 118 countries, with slightly different menus according to local tastes.[3]

By 2008 sales reached $22 billion a year, with most corporate profits coming from overseas units. Revenue to the central corporation grew 3% in the U.S. to $1.9 billion in the first three months of 2008 (plus much more to local franchisers), while profit climbed 5% to $682.5 million. European revenue climbed 23% to nearly $2.4 billion while, quarterly revenue in Asia, the Middle East and Africa grew 24% to about $1 billion.[4]

Cultural impact[edit]

see McDonaldization

But Americans have mixed feelings about it: is it a robust, succulent spheroid of fresh ground beef, the birthright of red-blooded citizens, providing good jobs for teenagers and a boost to the national economy? or is the Big Mac, mass-produced to industrial specifications and served as junk food by wage slaves to an obese population? Is it cooking or commodity? An icon of freedom or the quintessence of conformity?[5]

Along with Coca-Cola, the hamburger was once disdainfully regarded by many Europeans as the epitome of low cultural taste. With the advent of mass marketing from imitators of McDonald's such as Burger King, however, hamburgers have now spread around the world and, with variations, are consumed in every culture. Indeed, the Economist magazine uses the price of a Big Mac to compare the price levels of different economies because it is the single most nearly standardized product in most countries around the globe.

Ritzer (2000) argues that McDonald's has succeeded so well because it offers consumers, workers, and managers a maximum degree of efficiency, calculability, predictability, and control through non-human technology. These factors comprise a rational system, as first proposed by the German sociologist Max Weber. As with Weber's "iron cage of rationality," there is also a negative side to McDonaldization. Ritzer labels this "the irrationality of rationality", meaning that a rational system can produce a hail of irrational effects, from environmental damage to dehumanization of the workplace.[6] Watson (2006) points out that East Asian patrons often transform their neighborhood McDonald's into a local institution similar to a leisure center or a youth club.

American hamburger restaurant chains[edit]

- McDonalds

- Burger King

- Wendy's

- Jack in the Box

- Dairy Queen

- A & W

- Hardees/Carl's Jr.

- Whataburger

- In-n-Out Burger

- Sonic

- White Castle

Bibliography[edit]

- Debres, Karen. "Burgers for Britain: A Cultural Geography of McDonald's UK," Journal of Cultural Geography, Vol. 22, 2005 online edition

- Gross, Daniel. "Ray Kroc, McDonald's, and the Fast Food Industry," in Forbes Greatest Business Stories of All Time (1999) pp 177–92 online version

- Kroc, Ray. Grinding It Out: The Making Of McDonald's (1992) excerpt and text search

- Love, John F. McDonald's: Behind The Arches (1995) excerpt and text search

- Ozersky, Josh. The Hamburger: A History (Yale University Press: 2008), 160pp excerpt and text search

- Ritzer, George. The McDonaldization of Society (2000), 278pp

- Ritzer, George. McDonaldization: The Reader (2006) excerpt and text search

- Royle, Tony. Working for Mcdonald's in Europe: The Unequal Struggle? (2000) online edition

- Smith, Andrew F. Hamburger: A Global History (2008), 128pp excerpt and text search

- Watson, James. Golden Arches East: McDonald's in East Asia, (2nd ed. 2006) excerpt and text search

- "The Burger That Conquered the Country," Time Sep. 17, 1973 online

notes[edit]

- ↑ The American Heritage Cookbook and Illustrated History of American Eating & Drinking, Vol. 2, page 492

- ↑ Larousse Gastronomique, page 485

- ↑ Catherine Schnaubelt, "Global Arches: A Cultural Look at McDonald’s Franchises in Central Europe" online

- ↑ McDonald's owns most of its overseas outlets, but franchisers own most of the American outlets, and the corporation only counts the revenue it receives from franchisers. Total sales are therefore much higher than $8 billion in the U.S.

- ↑ Josh Ozersky, The Hamburger: A History (2008),

- ↑ Ritzer, 2000, pp. 16-18

KSF

KSF