Reconstruction

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 8 min

From Conservapedia - Reading time: 8 min

- Not to be confused with Deconstruction.

Reconstruction was the attempt from 1863 to 1877 in American history to resolve the issues of the American Civil War, when both the Confederacy and slavery were destroyed and the Constitution was expanded by three amendments that strengthened the rights of citizens. Reconstruction addressed the return of the Southern states that had seceded, the status of ex-Confederate leaders, and the Constitutional and legal status of the African-American Freedmen (newly freed ex-slaves). Violent controversy arose over how to accomplish those tasks, and by the mid 1870s Reconstruction had failed to equally integrate the Freedmen into the legal, political, economic and social system.

"Reconstruction" is also the common textbook name for the entire national history during 1865 to 1877.

Reconstruction came in three phases. Presidential Reconstruction 1863-66 was controlled by Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, with the goal of speedily reuniting the country. Their moderate programs were opposed by the Radical Republicans, a political faction that gained power after the 1866 elections and began Radical Reconstruction, 1866-1873 emphasizing civil rights and voting rights for the Freedmen. A Republican coalition of Freedmen, Carpetbaggers and Scalawags controlled most of the southern states. In the so-called Redemption, 1873-77, white supremacist Southern Democrats (calling themselves "Redeemers") defeated the Republicans and took control of each southern state, marking the end of Reconstruction.

Contents

Policy Issues[edit]

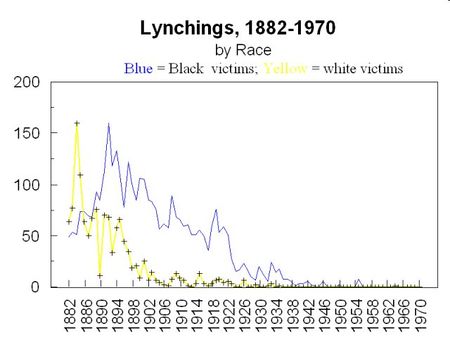

Source: Historical Statistics of the U.S., and is based on the 1952 Negro year Book.

There were conflicting theories of what the national government could and should do to restore the South to a normal status. The key constitutional provision was the national government must guarantee to every state a "republican form of government." Exactly what that meant was the issue. Radical Republican Charles Sumner argued that secession had destroyed statehood alone but the Constitution still extended its authority and its protection over individuals, as in the territories. Thaddeus Stevens and his followers viewed secession as having left the states in a status like newly conquered territory.

Congress rejected Johnson's argument that he had the war power to decide what to do, since the war was now over. Congress decided it had the primary authority to decide because the Constitution said the Congress had to guarantee each state a republican form of government; the issue became how the core political values of republicanism should operate in the South.

President Abraham Lincoln was the leader of the moderate Republicans and wanted to speed up Reconstruction and reunite the nation as soon as possible. Lincoln formally began Reconstruction in late 1863 with his Ten percent plan, which went into operation in several states but which Radicals opposed. Lincoln vetoed the Radical plan, the Wade-Davis Bill of 1864. The opposing faction of Radical Republicans were much more skeptical of Southern intentions and demanded far more stringent federal action. Congressman Thaddeus Stevens and Senator Charles Sumner led the Radical Republicans. After Lincoln's assassination, President Andrew Johnson switched from the Radical to the moderate camp. He too favored voting rights for the 170,000 black veterans.

Republican leaders agreed that slavery and the Slave Power had to be permanently destroyed, and that all forms of Confederate nationalism had to be suppressed. Moderates said this could be easily accomplished as soon as Confederate armies surrendered and the Southern states repealed secession and ratified the Thirteenth Amendment (which abolished slavery); all of which happened by September 1865, when Johnson felt Reconstruction was finished.

By 1866, however, Johnson, with no party affiliation, broke with the moderate Republicans and aligned himself more with the Democrats who opposed equality and the Fourteenth Amendment. Radicals attacked the policies of Johnson, especially his veto of the Civil Rights Bill for the Freedmen. The Ku Klux Klan was founded the same year by members of the Democratic Party to inflict violence against black leaders and white Republicans.[1] Its purpose was to take control and return Democrats to power. One of the founders, and the first "Grand Wizard," was former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Attempts were made to break up the Klan by President Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Army using the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act).

Republican empowerment of Blacks[edit]

Republicans stripped white males who engaged in rebellion against the United States of the vote, and gave it to Blacks. Newly freed Blacks held local, state and federal elected and non-elected positions as Republicans. The white males who were deprived of the vote were also barred from holding any civil service position and were universally Democrats. This disenfranchisement created enormous resentment among Democrats, so they formed the Ku Klux Klan to engage in voter intimidation and suppression.

The House elections of 1866 decisively changed the balance of power, giving the Radicals control of Congress and enough votes to overcome Johnson's vetoes and even to impeach him. Johnson was acquitted by one vote, but he remained almost powerless regarding Reconstruction policy. Radicals used the Army to take over the South and give the vote to black men, and they took the vote away from an estimated 10,000 or 15,000 white men who had been Confederate officials or senior officers. The Radical stage lasted for varying lengths in the different states, where a Republican coalition of Freedmen, Scalawags, and Carpetbaggers took control and promoted modernization through railroads and public schools. They were charged with corruption by their Southern Democrat opponents, calling themselves "Redeemers" after 1870.

Democrat Klan reaction[edit]

The Ku Klux Klan started attacking Black Republican conventions. At the Republican convention in Louisiana, the Klan joined with New Orleans police and New Orleans' Democrat mayor. The New Orleans Republican convention was attacked. 40 Blacks and 20 whites were killed. Another 150 were wounded. In 1868 the Democrats put out push cards in South Carolina listing what they called the 'radical' members of the South Carolina legislature. A push card is about the size of a baseball card. The cards had the pictures of 63 legislators they wanted to kill. 50 of the legislators were Black and 13 were white. All 63 were Republicans. On the back of the was the name of the legislator.

On election day, November 3, 1874, an Alabama chapter of the White League repeated actions taken earlier that year in Vicksburg, Mississippi. They invaded Eufaula AL, killing at least seven black Republicans, injuring at least 70 more, and driving off more than 1,000 unarmed Republicans from the polls.[2] The group moved on to Spring Hill AL, where members stormed the polling place, destroying the ballot box, and killing the 16-year-old son of a white Republican judge in their shooting.[3] The White League refused to count any Republican votes cast. But, Republican voters reflected the black majority in the county, as well as white supporters. They outnumbered Democratic voters by a margin greater than two to one. The League declared the Democratic candidates victorious, forced Republican politicians out of office, and seized every county office in Barbour County, Alabama.[4] Such actions were repeated in other parts of the South in the 1870s, as Democrats sought to regain political dominance in states with black majorities and numerous Republican officials. In Barbour County, the Democrats auctioned off as "slaves" (for a maximum cost of $2 per month), or otherwise silenced all Republican witnesses to the events. They were intimidated from testifying to the coup if the case went to federal court.[4]

By 1876, the situation had become ungovernable for Republicans.[5] The Republicans had been able to pass the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments which guaranteed Blacks basic equality and civil rights, but eventually had to declare an amnesty for whites who engaged in rebellion. Reconstruction ended, and Republicans withdrew from social engineering which had divided the country so deeply and stirred up such bitterness and hatred among Democrats toward both Blacks and Republicans. Reconstruction earned Republicans the undying hatred of Democrats.[6][7]

By 1877, however, Redeemers regained control of every state, and President Rutherford Hayes withdrew federal troops, causing the collapse of the remaining three Republican state governments. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments were permanent legacies. African Americans in the South were left to the mercy of increasingly hostile state governments dominated by white Democratic legislatures; neither the legislatures, law enforcement or the courts worked to protect freedmen.[8] As Democrats regained power in the late 1870s, they struggled to suppress black voting through intimidation and fraud at the polls. Paramilitary groups such as the Red Shirts acted on behalf of the Democrats to suppress black voting. From 1890 to 1908, 10 of the 11 former Confederate states passed disfranchising constitutions or amendments,[9] with provisions for poll taxes,[10] residency requirements, literacy tests,[10] and grandfather clauses that effectively disfranchised most black voters and many poor white people. The disfranchisement also meant that black people could not serve on juries or hold any political office, which were restricted to voters; those who could not vote were excluded from the political system. Bitterness and hatred of Republicans by Democrats created an enduring legacy lasting beyond the 20th century and into 21st century.

Further reading[edit]

See Reconstruction historiography for a much longer guide and an explanation of how historians have tackled the topic.

- Donald, David H. et al., Civil War and Reconstruction (2001) textbook

- Du Bois, W.E.B. "Reconstruction and its Benefits," American Historical Review, 15 (July, 1910), 781—99 JSTOR

- Donald, David Herbert. Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (1970), Pulitzer prize winning biography

- Dunning, William Archibald. Reconstruction: Political & Economic, 1865-1877 (1905). Blames Carpetbaggers for failure of Reconstruction. online edition

- Fitzgerald, Michael W. Splendid Failure: Postwar Reconstruction in the American South. (2007. xiv, 234 pp. isbn 978-1-56663-734-3.)

- Walter Lynwood Fleming The Sequel of Appomattox, A Chronicle of the Reunion of the States(1918). Dunning School[1].

- Foner, Eric and Mahoney, Olivia. America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War. short well-illustrated survey from neoabolitionist perspective

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (1988) Pulitzer-prize winning synthesis from neoabolitionist perspective

- Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. 2005. 268 pp. popular version from neoabolitionist perspective

- Ford, Lacy K., ed. A Companion to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Blackwell, 2005. 518 pp.

- Franklin, John Hope. Reconstruction after the Civil War (1961), University of Chicago Press, 280 pages. Short survey by leading black scholar

- Jenkins, Wilbert L. Climbing up to Glory: A Short History of African Americans during the Civil War and Reconstruction. SR Books, 2002. 285 pp.

- Litwack, Leon. Been in the Storm So Long (1979). Pulitzer Prize; focus on the African Americans from neoabolitionist perspective

- Milton, George Fort. The Age of Hate: Andrew Johnson and the Radicals. (1930). online edition Based on Dunning School

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. A History of the United States since the Civil War. Vol 1 and vol 2 (1917). Based on Dunning School vol 1 online, 1865-68

- Perman, Michael. Emancipation and Reconstruction (2003). 144 pp.

- Randall, J. G. The Civil War and Reconstruction (1953). Long the standard survey, with elaborate bibliography; updated by David Donald in 1961

- Rhodes, James G. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. Volume: 6. (1920). 1865-72; Highly detailed narrative by Pulitzer prize winner; argues was a political disaster because it violated the rights of white Southerners.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877 (1967); survey from neoabolitionist perspective

- Trefousse, Hans L. Historical Dictionary of Reconstruction Greenwood (1991), 250 entries

- Trefousse, Hans L. Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1989) online edition

- Trefousse, Hans L. Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian (1997)

- Williams, T. Harry. "An Analysis of Some Reconstruction Attitudes" The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Nov., 1946), pp. 469–486. JSTOR

Primary sources[edit]

- Fleming, Walter L. Documentary History of Reconstruction: Political, Military, Social, Religious, Educational, and Industrial 2 vol (1906). Uses broad collection of primary sources; vol 1 on national politics; vol 2 on states; volume 1 online 493 pp and vol 2 online 480 pp

- Lynch, John R. The Facts of Reconstruction. (1913)Full text online. Memoir by black congressmen from Mississippi during Reconstruction.

- McPherson, Edward, ed. The Political History of the United States of America During the Period of Reconstruction (1875), large collection of speeches and primary documents, 1865-1870, complete text online.

- Stalcup, Brenda. ed. Reconstruction: Opposing Viewpoints (Greenhaven Press: 1995). Primary documents from opposing viewpoints.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.history.com/topics/ku-klux-klan

- ↑ Mary Ellen Curtin, Black Prisoners and Their World, Alabama, 1865-1900, University Press of Virginia, 2000, p. 55

- ↑ Curtin (2000), Black Prisoners, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Curtin (2000), Black Prisoners, p. 56

- ↑ "the Compromise of 1877, which resolved the disputed presidential election of 1876 by awarding the presidency to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes (who had lost the popular vote) in exchange for the removal of federal troops from the South after the Civil War (which benefited Democrats, who wished to end Reconstruction and return white supremacy to southern state governments)." Gilded Age politics: patronage. khanacademy.org

- ↑ See for example James O'Keefe debate with Hairy Hillbilly Hippie for an example of a partisan Democrat who votes against his own economic interests.

- ↑ See excerpt from Dinesh D'Souza's, Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party, Regnery Publishing, July 18, 2016.

- ↑ Finkelman, Paul (2006). Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties.

- ↑ Chafetz, Joshua Aaron (2007). Democracy's Privileged Few.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Klarman, Michael J. (2004). From Jim Crow to Civil Rights.

KSF

KSF