Instrumentation

From EduTechWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From EduTechWiki - Reading time: 4 min

- By Alain Senteni, University of Mauritius and Daniel K. Schneider.

Definition[edit | edit source]

Béguin and Rabardel (2000) define a mediating instrument by its two components: (1) an artifact component which may be material or symbolic, produced by the subject or by others; and (2) one or more associated schemes, resulting from a construction specific to the subject, or through the appropriation of pre-existing social schemes.

“The process of transforming an artifact into an instrument of human activity is a developmental process of its own (see Virkkunen and Ahonen 2007). Pierre Rabardel and his colleagues have examined the dynamics of such processes of “instrument genesis” (Vérillon and Rabardel 1995; Béguin and Rabardel 2000). The first stage of the process involves shaping, adapting, and tailoring the artifact according to the local needs and requirements of activity. A teacher who selects a technology-enhanced learning environment and designs, jointly with students (and researchers), knowledge-building projects to be pursued, has a critical role in this instrumentation process. The second stage focuses on developing and cultivating personal and collective practices needed for productively using the artifact as an instrument in knowledge-building activity. The gradual instrumentalization process takes time and depends on the involved agents’ own intensive participation in the collective inquiry process. It involves a developmental process in which the instrument gradually merges or fuses in the participants’ transforming activity system (Engeström 1987).” (Hakarainen, 2009).

See also: cognitive tool, external cognition

The instrument as mediator[edit | edit source]

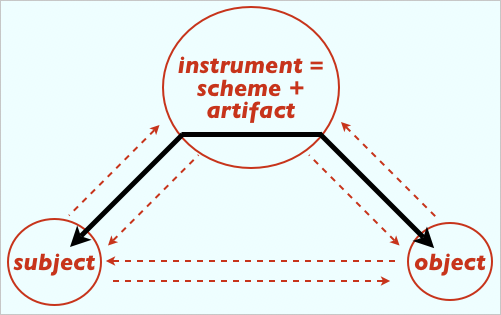

Together, scheme plus artifact act as the mediator between the subject and the object of his/her activity : “An activity consists of acting upon an object in order to realize a goal and give concrete form to a motive. Yet the relationship between the subject and the object is not direct. It involves mediation by a third party: the instrument [...] An instrument cannot be confounded with an artifact. An artifact only becomes an instrument through the subject's activity. In this light, while an instrument is clearly a mediator between the subject and the object, it is also made up of the subject and the artifact.” (Béguin & Rabardel, 2000, P.175)

The instrument in transformative pedagogy[edit | edit source]

Deemed to operate mainlly in pre-computerised contexts, or in contexts where computerization is shyly emerging, transformative pedagogy (TP) is interested in the construction of new social schemes or in the appropriation of pre-existing social schemes. In developing countries whose context brings it back to its historical roots, TP should provide support and careful mentoring for ICT integration and effective use, failing which technological progress and infrastructure development cannot really be (cost)-effective, creating isolated micro-cyberislands with little impact on the overall development of the countries. TP's focus is then kept on facilitation and development of social schemes rather than on the production-alteration-improvement of new artifacts. In a first phase, the schemes addressed by TP regard essentially the appropriation, integration, effective use and cultural (rather than technical) contextualisation of artifacts, a good part of them being often developed elsewhere, particularly for the digital ones. If TP encourages knowledge creation, it must before all develop and support its presupposed social practices from the primary school level to tertiary education, in order to help the learners to create a synergy amongst their individual cognitive resources for the production of shared knowledge objects.

In the perspective of transformative pedagogy, i.e. a evolutionary and systemic perspective on education and culture in which pragmatic concepts are elaborated through an historical and social construction within communities and work collectivities (Rabardel & Béguin, 00), technology is merely seen as the mediating instrument of human learning activity.

As argued by researchers from the Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning (CSCL) community (Koschmann, 2002)(Stahl, 2002ab), a better understanding of the functioning of artifacts, digital or conceptual, helps understand how to effectively foster and convey collaborative meaning-making. A look at the history of transformative pedagogy (e.g. the European New Education movement) shows that these artifacts evolve more rapidly than the pedagogical goals and objectives they are created to mediate.

References[edit | edit source]

- Béguin, Pascal (2003), Design as a mutual learning process between users and designers, Interacting with Computers, Volume 15, Issue 5, October 2003, Pages 709-730. doi:10.1016/S0953-5438(03)00060-2

- Béguin, P. and Rabardel, P. 2000. P. Designing for instrument-mediated activity. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 12 (2000), pp. 173-191.

- Brodin, E. (2002). Innovation, instrumentation technologique de l'apprentissage des langues : des schèmes d'action aux modèles de pratiques émergentes In ALSIC. Vol. 5, Numéro 2, décembre 2002.

- Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

- Hakkarainen, Kai. A knowledge-practice perspective on technology-mediated learning, International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 2009, 4, 2, 213, http://www.springerlink.com/content/uv0877t363np7375/

- Koschmann, T. (2002) Dewey's Contribution to the Foundations of CSCL Research, CSCL 2002 Proceedings, pp.17-23, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Hillsdale, New Jersey

- Lameul, G. (2002). Médiatisation de la relation pédagogique et posture enseignante.PDF

- Lonchamp, J. (2012). An instrumental perspective on CSCL systems. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 7(2), 211-237. Abstract, PDF (Access restricted)

- Rabardel, P. (1995). Les Hommes et les technologies une approche cognitive des instruments contemporains. Paris : Université de Paris 8. pdf1 and pdf2

- Rabardel, P. (1995). Les hommes et les technologies, approche cognitive des instruments contemporains. Armand Colin : Paris.

- Stahl, G. (2002b) Contributions to a Theoretical Framework for CSCL, CSCL 2002 Proceedings, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA

- Sorensen, Estrid (2009). The Materiality of Learning: Technology and Knowledge in Educational Practice (Learning in Doing: Social, Cognitive and Computational Persp), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521882087

- Trouche, L. (2005). Des actefacts aux instruments, une approche pour guider et intégrer les usages des outils de calcul dans l'enseignement des mathématiques. Actes de l'Université d'été de Saint-Flour. Word

- Vérillon, P. & Rabardel, P. (1995). Cognition and artifacts: A contribution to the study of thought in relation to instrumented activity. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 10(1).

- Virkkunen, J., & Ahonen, H. (2007). Learning in transformation: A new instrument for renewing learning practices (in Finnish). Vantaa: Infor.

KSF

KSF