Open Education Roadmap

From EduTechWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From EduTechWiki - Reading time: 16 min

DOI[edit | edit source]

Please note that a static pdf report has been created on August 17, 2022 for ease of cross-referencing. It is accessible on Zenodo through https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7002915

Executive summary[edit | edit source]

This page is the main output of a scientific exchange among a group of 10 Swiss and International scholars who have been drafting a roadmap for Open Education in the Swiss Higher Education landscape. The roadmap is situated as the epistemic level and organised around 3 main strategic focuses and each focus is detailed in 4 actions. Focus 1 reads: Broad horizon education; Focus 2: Ethical and responsible use of technology and Focus 3: Humans reconnected to the planet’s ecosystem.

This work stems from a Delphi study with worldwide Open Education experts, workshop held at two Open Education events - Open Education Global and Swiss Open Education Day, 9 months of work and a vision exercice, projecting the kind of education we would like in 50 years.

Stakeholders, citizens and communities are invited to join and actively contribute to the discussion. Once agreement is reached at the epistemic level, concrete plans to operationalise each action and make it reality becomes possible.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different.

It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead

ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.” Peters et al. (2020, p. 1)

A roadmap for Open Education in the Swiss Higher Education landscape has been drafted in 2021-2022. The output is available from this page.

Within a SNSF scientific exchange, Swiss and international scholars have been working for 9 months on an Open Education project, driven by three aims:

- Draft a roadmap for Open Education in the Swiss Higher Education landscape to set an initial ground and open discussions to stakeholders, citizens and communities;

- Identify key stakeholders, ready to act as change agents in Swiss Higher Education institutions (HEIs) and take on leadership roles with regard to Open Education;

- Start a Swiss Open Education network to share and coordinate future actions.

What is Open Education? How is it related to Open Science and other Opens and Commons? Why does it matter for Higher Education institutions? Why does Open Education matter for each and every citizen?

This report provides an overview of Open Education to interested parties through these 4 questions and sets the ground to invite stakeholders, citizens and communities to actively contribute to the debate.

What is Open Education?[edit | edit source]

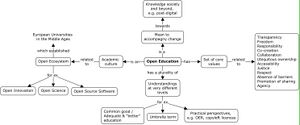

Many definitions of Open Education exist (e.g. Year of Open; Stracke, 2019, p. 184 “Open Education is designing, realizing, and evaluating learning opportunities with visionary, operational, and legal openness to improve learning quality for the learners”): and this diversity is characteristic of its openness. Below is a tentative definition of how we understand it today and a visual representation of its main characteristics (Figure 1).

Open Education is both an umbrella term and a complex ecosystem that operates on a number of very different levels. It is inherently open in the way it functions and cannot be captured by a single definition. It considers knowledge as a common good. Its intrinsic values of freedom and transparency assure contribution and access to the discovering of all forms of knowledge, under the sole condition of respecting authorisation to access it, e.g. indigenous knowledge. It is articulated around the remaining values of responsibility, sharing, justice, agency and ubiquitous ownership (Baker, 2017). It is neither synonymous of free nor of extractive approaches. It strives to find sustainable models at all levels – epistemic, legal, social, economic, political, ecologic, infrastructure, etc. Open Education represents an alternative approach that exists since the Middle Ages and is at the heart of the establishment of European universities (see for ex. Peter & Deimann, 2013, p. 9). It is a means (Paola Corti, 2022, private communication) to foster knowledge societies by leveraging collective human intelligence.

[edit | edit source]

Openness is not binary, i.e. on/off and is best understood on a continuum. As a conceptual tool, we may distinguish 3 types of practices on this continuum that can be entangled: closed, semi-open and open. We make this choice because the dualism open-closed does not exist per se (Hilton et al., 2010; Wiley, 2009, No date).

Open Education is one component of the Open Ecosystem. To give an idea of the breadth and depth of this ecosystem, the metaphor of the tree by Stacey (2018) is insightful and sets the direction, with elements that are already bearing fruits, e.g. Open Science, Open Source Software, and others which are germinating, e.g. Open Institutions, Open Education Data.

The Swiss higher education landscape seeks to ground Openness and has already adopted national policies for Open Access and Open Research Data. In addition, some HEIs have a policy for Open Educational Resources (OER), e.g. Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, Pädagogische Hochschule Bern. Swissuniversities, within its P8 programme funds the Swiss Digital Skills Academy which promotes OER and Open platforms. Reports are available (e.g. Gutknecht et al., 2020; Neumann et al., 2022) and interest groups on Open Educational Resources exist.

Education is at a crossroads striving for more social oriented forms with collaborative practices and commoning perceived as opportunities to move forward (Le Crosnier, 2017). Switzerland is a fertile ground to revive and reinvent commoning because it can build on its historical background with natural commons. Commoning represents also a very interesting political structure that empowers citizens and communities (Haller et al., 2021). This is important because political choices do influence HEIs’ path and are critical in terms of bifurcations (Kauko, 2014). In addition, it makes sense that main actors, i.e. citizens and communities, for whom education is being designed are involved in bargaining powers. Education is considered a knowledge commons (Hess et Ostrom, 2007) and can benefit from the experience with natural commons management.

Why does Open Education matter for Higher Education institutions?[edit | edit source]

Higher Education institutions (HEI) have 3 missions: teaching, research and service to the society[1]. In their recent history, HEIs were founded on the Humboldtian model of combining holistically research and teaching (De Meulemeester, 2011). In the Global North, research has been predominant in the last decades, and logically, Openness has arrived through this mission, reviving Open Science. The World Wide Web has been primarily created to exchange research data and results among researchers worldwide (CERN, No date) leveraging values of Openness founded in the Middle Ages (David, 1998; Langlais, 2015).

Today, HEIs evolve in complex international and national power structures and have to consider and negotiate with a variety of international organisations like the UN, EU, OECD, WEF, GAFAM, etc. (e.g. for Portugal, see Santos et Kauko, 2022).

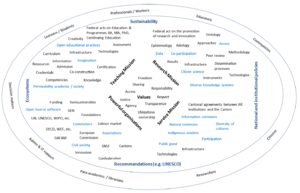

Within this extraordinary entanglement of power structures, we try to capture some elements for each of the 3 missions of HEIs, demonstrating with the blue font that threads of Openness do already exist and Open Education can benefit from it to grow (Figure 2).

Suggesting a Roadmap for Open Education in the Swiss Higher Education landscape[edit | edit source]

In this section, we present the roadmap. The following sections explain how we proceeded to reach this outcome.

An overall framework and operating conditions for the roadmap provides enabling contexts. Three strategic focus organise then the roadmap, each containing four actions as detailed below.

| Overall framework and operating conditions for the roadmap:

Enabling legal, societal, political, economic and institutional ecosystems to support Openness and a renewed approach to Commons. |

| Strategic focus 1: Broad horizon education

Action 1: Be knowledgeable of one's own cultural contexts and develop a robust critical and multi-perspective historical memory. Action 2: Accept, respect and find bridges with other knowledge systems in the pursuit of deep cultural, epistemic, social and racial justice. Action 3: Create a context for education with global equity and guarantee participation in Knowledge creation processes worldwide. Action 4: Open the governance of Education to alternative systems that foreground humans and communities, e.g. Buen vivir & Buen conocer, Ubuntu approach, First Nations culture.

Action 1: Use collective intelligence to put technology at the service of global common good. Action 2: Use technology in responsible and intelligent ways in order to develop truly cutting-edge technology. Reserve it for what can only be done with technology for evident sustainability issues. Action 3: Raise awareness about techno-coloniality, techno-utopia and the pharmakon role that technology plays to free humans from non-productive considerations towards technology. Action 4: Develop smart collaboration between humans and technology and not a fusion.

Action 1: Raise awareness of humans’ responsibility in the preservation of our planet’s ecosystem and all its species, including humans. Action 2: Discover the variation of understandings of how Nature can be perceived according to the diversity of knowledge systems. Action 3: Renovate education to adopt an eco-responsible perspective with well-thought uses of energies. Action 4: Leverage co-creation and recycling to break with current consumerist, extractivist and planned scarcity models. |

Methodology and context[edit | edit source]

Method[edit | edit source]

In this foresight context, i.e. Openness and knowledge society, the aim is to elicit expert knowledge to better understand what is at stake. We have chosen to use an open Delphi approach (Linstone et Turoff, 2002; Okoli et Pawlowski, 2004; Stockinger, 2015) and an expert panel discussion (EuropeanForesightPlatform, No date).

Delphi method’s characteristics are three: i) a multiphase feedback from experts with each round feeding back into the next in order to reach consensus; ii) a variety of experts in the same field but with different perspectives, positions, etc.; iii) anonymity from one round to the next.

During the first round, anonymity criteria have intentionally not been respected to create links between content provided and experts (Lewthwaite et Nind, 2016; Piron, 2017). The second round was anonymous.

The Delphi study questionnaire addresses 7 dimensions: economic, legal, technology, research, epistemology, policies and stakeholders. It has been sent on July 15th, 2021 as one entire block and then sent a second time, part by part, between November and December 2021.

Answers have been analysed in workshops and among the group of scholars. In pairs, or groups of 3 scholars for each dimension, key concepts have been organised on padlets. Experts voted during both face-to-face workshops: the one during the Swiss Open Education day and the one during the Open Education Global conference and some voted on-line within the 2 weeks following the workshops.

Data collected with the Delphi method is following:

Round 1: answers to the Delphi questionnaire (July-Dec 2021)

- 5 full answers (2 hours survey!) & 4 partial answers

- Part 1 (OE from your perspective): 5 answers

- Part 2 (policy & legal): 5 answers

- Part 3 (economic & technology): 2

- Part 4 (research): 0

Round 2: answers vary per topic between 2 participations (research) and 15 participations (economic) Data collected with the expert panel discussion refer on one hand to discussions held during both workshops and on the other hand to discussions held within the group of scholars throughout the 9 months. This work crystallised in the vision exercise outlined below in the dedicated section.

Timeline[edit | edit source]

This roadmap is the result of a 9 months’ collaboration between Swiss and international scholars engaged in Open Education (Figure 3).

Findings[edit | edit source]

Delphi study answers - 1st round[edit | edit source]

Answers have been organised per level and are available from:

https://tecfa.unige.ch/perso/class/OE-General/DelphiSurveyDataProcessed-Q1-8.pdf (Questions 1 to 8)

https://tecfa.unige.ch/perso/class/OE-General/DelphiSurveyDataProcessed-Q9-23.pdf (Questions 9 to 23)

Synthesis from the 2nd round of the Delphi study[edit | edit source]

Answers have been organised per level and are synthesised below, in terms of what to consider in priority (higher number of votes per item).

At the economic level:

- Consider Education as a value and not as a product

- Open is not free, it costs

- Sharing boosts creativity

- Sharing / pooling to reduce waste of energy and resources; to value work conducted within communities which is dissociated from monetary value and not captured by the market

- Foster social entrepreneurship

- Foster durability and sustainability

At the legal level:

- Shift from an extractive to a generative legal framework

- Foster the dissemination and adoption of libre licences and fair use

- Ensure the legal recognition of the rights associated with commons

- Advance laws and policies to enshrine public right to knowledge

At the policy level:

- Establish national policies to enable open actions

- Define clear aims for the policy (Is it a legal instrument, i.e. regulations, laws? Is it an economic instrument, i.e. funding? Is it an information instrument, i.e. to persuade? Is it a coordination instrument, i.e. monitoring policy compliance? Is it a technical assistance instrument, i.e. capacity building?)

- Elaborate institutional policies to support and value openness

At the epistemological level:

- Enable co-creation in education

- Leverage collaboration as an ability to work together and enhance each other's work

- Foster openness, inclusiveness, fairness, transparency and diversity

At the technological level:

- Find Open Educational Resources

- Ensure accessibility

- Develop collaborative tools

- Create open platforms and ecosystems

At the research level:

- Foster collaborative learning

- Identify and take action against social inequalities

- Develop innovative pedagogical practices

At the stakeholders' level:

- Strengthen educational institutions as major actors

- Foster implemention and sharing as major actions and practices

Major open questions concern: which legal contexts for education?[edit | edit source]

The main questions concern legal dispositions towards education in HEIs and communities: what does exist? Which are the active and potential dormant law that could concern Open Education? Does a federal act on Education, similar to the federal act on the promotion of research and innovation exist? Do cantonal acts exist? How is the content of the Constitution (Section 3) with regard to education leveraged?

Are any future actions with regard to the federal acts on continuing education, the federal act on funding and coordination of the Swiss Higher Education sector, the federal act on vocational and professional education and training envisaged? Does a federal act on commons exist or is in the making as it seems to be the case in France?

What exists with regard to Education in international law? On which laws does the SDG 4, quality education for all, rely on?

Our vision for Education in 50 years[edit | edit source]

To draft the roadmap, in addition to data gathered within the Delphi study, the need for a compass was expressed. Within the group of scholars, we decided to make the following exercise to actually find this compass - answer the question: What kind of education would we like in 50 years?

The outcome of this exercise materialises in:

- three main strategic focus and a set of respective actions detailed above;

- role modelling starting from what exists and projecting where it can lead in 50 years.

Scholars tried to imagine how concrete current Higher Education practices may evolve in 50 years with regards to the three strategic focus (Figure 4). Below we explain the different elements of Figure 4, namely current practices, bifurcations and dimensions supportive of Openness.

Current practices[edit | edit source]

Current practices are captured into three categories, i.e. closed, semi-open and open practices. Closed practices are featured for example as the individual design of a course for a specific paying target audience, e.g. a Bachelor course, with the support of GAFAM tools, e.g. Windows, Office, Google, etc.

Semi-open practices are featured as practices that tend towards some kind of openness, particularly in terms of access, e.g. MOOCs distributed on commercial platforms. They remain closed at the epistemic level, usually conceived by a cultural and professional uniform body of stakeholders without reaching out to any other actor. These practices remain closed at the technologic level because they do not provide the material with copyleft licences that would allow their reuse. At the economic level, they are said to be free, at least until certification, but collect personal and learning analytics data.

Open practices’ characteristics are co-designed courses with participatory approaches including stakeholders, e.g. students, communities of interest. These practices have strong links with the society, reach out beyond academia and enable the development of diverse theoretical and practical knowledge and competences through interactions, e.g. citizen science, wikis, fablabs, hackathon, etc., leveraging collective intelligence.

Bifurcations[edit | edit source]

Bifurcations are of utmost importance. Renewing and changing the direction of one’s practices, as an institution or an individual is always possible even if change demands energy both to leave “habits” and to face resistance. To what extent can the challenge be considered worth the fight? In the end, is it about retrieving some bargaining power to fight for freedom and transparency?

Dimensions supportive of Openness[edit | edit source]

Dimensions that can be introduced and/or supported more powerfully are open values, commons’ rules and digital sustainability. These are key to move from an individualistic, market-led Higher Education landscape to a landscape that considers Education as a common good and strives for co-creation with deep participatory approaches and epistemic justice.

Open values can be synthesised in two major ones: freedom and transparency. All the remaining ones, i.e. accessibility, justice, respect, absence of barriers, promotion of sharing, agency and ubiquitous ownership, stem from the first two (Baker, 2017).

In terms of commons, Switzerland is known for the management of its natural commons which has persisted since the Middle Ages (Haller et al., 2021; Ostrom, 1990) whereas it has been replaced by hierarchical and proprietary ways of managing resources in many surrounding countries. Commoners in Switzerland have a real bargaining power and can leverage the legal setting. Recent research and action in the domain of natural commons is inspiring to address the management of knowledge commons. Indeed, education is part of knowledge commons. Currently, for example, stakeholders have raised awareness about the fact that SDGs do not consider commons. They work towards finding solutions to reorient this and consider the commons in sustainability discussions (Haller, 2022; Larsen et al., 2022). Should not we join this endeavour to include knowledge commons in these discussions? Especially since SDG 4, quality education for all, concerns education?

Finally, Digital sustainability refers to intergenerational justice, regenerative capacity, economic use of resources, risk reduction, absorptive capacity and ecological and economic added value. A digital artefact should be integrated in an ecosystem thought for continuous recycling from creation to use. This ecosystem materialises in variables such as open licensing regime, shared tacit knowledge, participatory culture, good governance and diversified funding (Stuermer, 2014; Stuermer et al., 2017).

Limits and next steps[edit | edit source]

Limits[edit | edit source]

Reminding Einstein's thought was insightful - “I believe in intuition and inspiration. Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

Contributing scholars have committed to this project for their sense of responsibility towards society and future generations. They have leveraged imagination. The output of their work has the limits of this exploratory study. For instance, data processed and presented on padlets are situated at different levels. Padlets themselves are very different in nature. Scholars are fully aware of this. These findings represent a first step to find consistent support and start discussions and actual research on Open Education in the Swiss Higher Education landscape.

Next steps[edit | edit source]

Next steps consist in disseminating findings and discussing Open Education with a variety of stakeholders inside and outside academia.

Next steps will also address role modelling and showcasing examples of potential bifurcations, particularly by leveraging initiatives that exist worldwide.

To what extent can Open Education represent a means to move towards the knowledge society and the post-digital (Savin-Baden, 2022)? This is also a guiding question for a next step.

Key stakeholders[edit | edit source]

Support[edit | edit source]

In the Swiss Higher Education landscape, we have identified and do network with the following organisations or individuals pertaining to these organisations:

- CH Open and more specifically the Open Education Day which support the project;

- EPFL which is very active with regard to Open Educational Resources at the level of practitioners, i.e. teachers with the P8 Swissuniversity funded Digital Skill Academy project, former GRAASP project and library project;

- The Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften (ZHAW) which is very active in the domain of Open Educational Resources, specifically in terms of national policies (Gutknecht et al., 2020; Neumann et al., 2022) and in their involving students in OER;

- ETHZ which is very active with regard to decentralised and innovative Open Learning Credentialing and Management System;

- EduHub which hosts a long-standing interest group on OER, active the last 10 years, organising conferences, writing reports, networking across the Swiss HE landscape;

- The University of Basel which is involved Openness at the policy level and produces very interesting science and technology studies;

- The University of teacher education Luzern which is involved in OER;

- In Ticino, SUPSI and USI which show interest but have not contributed yet to the project, asking to be informed of its output;

- One person from SFUVET and one person from Swissuniversities who also wish to be kept informed of the project’s outcomes.

Of course, scholars pertaining to this Scientific exchange and working in the Swiss HE landscape have supportive institutions: University of Geneva, University of teacher education Bern / Zurich / Valais, HES-SO, House of commons.

At the international level, individuals pertaining to the following organisations do support our project through fruitful collaboration:

Open Education Global francophone;

Universities of Nantes, de la Rioja, Lille, Open University, and Rabat.

Direct contributors[edit | edit source]

Lead and coordination: Barbara Class

Scientific Exchange group of contributors:Fabio Balli, Alexandre Enkerli, Sandrine Favre, Denis Gillet, Iris Hensler, Thomas Hervé Mboa Nkoudou, Michele Notari, Yvonne Scherrer, Guillaume Tschupp.

Additional outputs for the medium-term[edit | edit source]

Some additional outputs of the project can be mentioned here. Several spaces and initiatives have been launched during the project and need to be organised properly:

- A work in progress whitepaper , on a participatory wiki, targeted to teachers who want to know more about Open Education Practices. It was started in French and translated into English and German. Current state: draft. This whitepaper was presented during the OER#22, the 13th annual conference for Open Education research, practice and policy.

- A work in progress Frequently Asked Question on Open Education that is not targeted to any specific audience. Current state: draft.

- A wiki page we have set up to support our work during the Open Education Conference in Nantes which contains many references. Current state: achieved for this stage of the project.

- A wiki page that supported a workshop on Open Educational Resources. Current state: achieved for this first workshop and basis for any future similar workshop.

Funding[edit | edit source]

SNSF scientific exchange: https://data.snf.ch/grants/grant/205792

References[edit | edit source]

Baker, F. W. (2017). An Alternative Approach: Openness in Education Over the Last 100 Years. TechTrends, 61(2), 130-140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0095-7

CERN. (No date). The birth of the Web. https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web

David, P. A. (1998). Common Agency Contracting and the Emergence of "Open Science" Institutions. The American Economic Review, 88(2), 15-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/116885

De Meulemeester, J.-L. (2011). Quels modèles d’université pour quel type de motivation des acteurs ? Une vue évolutionniste. Pyramides, 21, 261-289.

EuropeanForesightPlatform. (No date). How to do Foresight? http://www.foresight-platform.eu/community/forlearn/how-to-do-foresight/

Gutknecht, P., Reimer, R. et Luthi, G. (2020). Report on the Open Educational Resources (OER) survey at Swiss Universities. https://www.eduhub.ch/export/sites/default/files/OER_Bericht_0.9_zhd_swissuniversities_enL.pdf

Hess, C., & Ostrom, E. (Eds.). (2007). Understanding Knowledge as a Commons - From Theory to Practice. Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6980.001.0001 .

Haller, T. (2022). The SDGs run the risk of becoming an anti-politics machine. https://www.cde.unibe.ch/research/cde_series/the_sdgs_run_the_risk_of_becoming_an_anti_politics_machine/index_eng.html

Haller, T., Liechti, K., Stuber, M., Viallon, F.-X. et Wunderli, R. (dir.). (2021). Balancing the Commons in Switzerland: Institutional Transformations and Sustainable Innovations. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003043263

Hilton, J., Wiley, D., Stein, J. et Johnson, A. (2010, 2010/02/01). The four ‘R’s of openness and ALMS analysis: frameworks for open educational resources. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 25(1), 37-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510903482132

Kauko, J. (2014, 2014/10/21). Complexity in higher education politics: bifurcations, choices and irreversibility. Studies in Higher Education, 39(9), 1683-1699. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.801435

Langlais, P.-C. (2015). Quand les articles scientifiques ont-ils cessé d’être des communs ? Sciences Communes. https://scoms.hypotheses.org/409

Larsen, P. B., Haller, T. et Kothari, A. (2022, 2022/05/01/). Sanctioning Disciplined Grabs (SDGs): From SDGs as Green Anti-Politics Machine to Radical Alternatives? Geoforum, 131, 20-26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.02.007

Le Crosnier, H. (2017). La culture numérique a-t-elle besoin de médiation ? Cahiers de l’action, 48(1), 9-14. https://doi.org/10.3917/cact.048.0009

Lewthwaite, S. et Nind, M. (2016). Teaching Research Methods in the Social Sciences: Expert Perspectives on Pedagogy and Practice. British Journal of Educational Studies in Continuing Education, 64(4), 413-430. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2016.1197882

Linstone, H. et Turoff, M. (2002). The Delphi Method, Techniques and applications. New Jersey Institute of Technology.

Neumann, J., Schön, S., Bedenlier, S., Ebner, M., Edelsbrunner, S., Krüger, N., Lüthi-Esposito, G., Marín, V. I., Orr, D., Peters, L. N., Reimer, R. T. D. et Zawacki-Richter, O. (2022). Approaches to Monitor and Evaluate OER Policies in Higher Education - Tracing Developments in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 17(1), 125-147. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6508522

Okoli, C. et Pawlowski, S. D. (2004, 2004/12/01/). The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15-29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2003.11.002

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807763

Peter, S. et Deimann, M. (2013). On the role of openness in education: A historical reconstruction. Open Praxis, 5(1), 7-14. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.5.1.23

Peters, M. A., Rizvi, F., McCulloch, G., Gibbs, P., Gorur, R., Hong, M., Hwang, Y., Zipin, L., Brennan, M., Robertson, S., Quay, J., Malbon, J., Taglietti, D., Barnett, R., Chengbing, W., McLaren, P., Apple, R., Papastephanou, M., Burbules, N., Jackson, L., Jalote, P., Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Fataar, A., Conroy, J., Misiaszek, G., Biesta, G., Jandrić, P., Choo, S. S., Apple, M., Stone, L., Tierney, R., Tesar, M., Besley, T. et Misiaszek, L. (2020). Reimagining the new pedagogical possibilities for universities post-Covid-19. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1777655

Piron, F. (2017). Méditation haïtienne : répondre à la violence séparatrice de l’épistémologie positiviste par l’épistémologie du lien. Sociologie et sociétés, 49(1), 33-60. https://doi.org/10.7202/1042805ar

Santos, Í. et Kauko, J. (2022, 2022/05/04). Externalisations in the Portuguese parliament: analysing power struggles and (de-)legitimation with Multiple Streams Approach. Journal of Education Policy, 37(3), 399-418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2020.1784465

Savin-Baden, M. (2022). The death of data interpretation and throwing sheep in a postdigital age. Education Ouverte et Libre - Open Education, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.52612/journals/eoloe.2022.e11.754

Stacey, P. (2018). Starting Anew in the Landscape of Open. https://edtechfrontier.com/2018/02/08/starting-anew-in-the-landscape-of-open/

Stockinger, H. (2015). The future of augmented reality - an Open Delphi study on technology acceptance. International Journal of Technology Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTMKT.2016.073372

Stuermer, M. (2014). Characteristics of digital sustainability. Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Guimaraes, Portugal. https://doi.org/10.1145/2691195.2691269

Stuermer, M., Abu-Tayeh, G. et Myrach, T. (2017, 2017/03/01). Digital sustainability: basic conditions for sustainable digital artifacts and their ecosystems. Sustainability Science, 12(2), 247-262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0412-2

Wiley, D. (2009). Defining “Open”. https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/1123 Wiley, D. (No date). Defining the "Open" in Open Content and Open Educational Resources. https://opencontent.org/definition/

KSF

KSF