3-manifold

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

In mathematics, a 3-manifold is a topological space that locally looks like a three-dimensional Euclidean space. A 3-manifold can be thought of as a possible shape of the universe. Just as a sphere looks like a plane (a tangent plane) to a small and close enough observer, all 3-manifolds look like our universe does to a small enough observer. This is made more precise in the definition below.

Principles

Definition

A topological space is a 3-manifold if it is a second-countable Hausdorff space and if every point in has a neighbourhood that is homeomorphic to Euclidean 3-space.

Mathematical theory of 3-manifolds

The topological, piecewise-linear, and smooth categories are all equivalent in three dimensions, so little distinction is made in whether we are dealing with say, topological 3-manifolds, or smooth 3-manifolds.

Phenomena in three dimensions can be strikingly different from phenomena in other dimensions, and so there is a prevalence of very specialized techniques that do not generalize to dimensions greater than three. This special role has led to the discovery of close connections to a diversity of other fields, such as knot theory, geometric group theory, hyperbolic geometry, number theory, Teichmüller theory, topological quantum field theory, gauge theory, Floer homology, and partial differential equations. 3-manifold theory is considered a part of low-dimensional topology or geometric topology.

A key idea in the theory is to study a 3-manifold by considering special surfaces embedded in it. One can choose the surface to be nicely placed in the 3-manifold, which leads to the idea of an incompressible surface and the theory of Haken manifolds, or one can choose the complementary pieces to be as nice as possible, leading to structures such as Heegaard splittings, which are useful even in the non-Haken case.

Thurston's contributions to the theory allow one to also consider, in many cases, the additional structure given by a particular Thurston model geometry (of which there are eight). The most prevalent geometry is hyperbolic geometry. Using a geometry in addition to special surfaces is often fruitful.

The fundamental groups of 3-manifolds strongly reflect the geometric and topological information belonging to a 3-manifold. Thus, there is an interplay between group theory and topological methods.

Invariants describing 3-manifolds

3-manifolds are an interesting special case of low-dimensional topology because their topological invariants give a lot of information about their structure in general. If we let be a 3-manifold and be its fundamental group, then a lot of information can be derived from them. For example, using Poincare duality and the Hurewicz theorem, we have the following homology groups:

where the last two groups are isomorphic to the group homology and cohomology of

, respectively; that is,

From this information a basic homotopy theoretic classification of 3-manifolds[1] can be found. Note from the Postnikov tower there is a canonical map

If we take the pushforward of the fundamental class

into

we get an element

. It turns out the group

together with the group homology class

gives a complete algebraic description of the homotopy type of

.

Connected sums

One important topological operation is the connected sum of two 3-manifolds

. In fact, from general theorems in topology, we find for a three manifold with a connected sum decomposition

the invariants above for

can be computed from the

. In particular

Moreover, a 3-manifold

which cannot be described as a connected sum of two 3-manifolds is called prime.

Second homotopy groups

For the case of a 3-manifold given by a connected sum of prime 3-manifolds, it turns out there is a nice description of the second fundamental group as a

-module.[2] For the special case of having each

is infinite but not cyclic, if we take based embeddings of a 2-sphere

where

then the second fundamental group has the presentation

giving a straightforward computation of this group.

Important examples of 3-manifolds

Euclidean 3-space

Euclidean 3-space is the most important example of a 3-manifold, as all others are defined in relation to it. This is just the standard 3-dimensional vector space over the real numbers.

3-sphere

A 3-sphere is a higher-dimensional analogue of a sphere. It consists of the set of points equidistant from a fixed central point in 4-dimensional Euclidean space. Just as an ordinary sphere (or 2-sphere) is a two-dimensional surface that forms the boundary of a ball in three dimensions, a 3-sphere is an object with three dimensions that forms the boundary of a ball in four dimensions. Many examples of 3-manifolds can be constructed by taking quotients of the 3-sphere by a finite group acting freely on via a map , so .[3]

Real projective 3-space

Real projective 3-space, or RP3, is the topological space of lines passing through the origin 0 in R4. It is a compact, smooth manifold of dimension 3, and is a special case Gr(1, R4) of a Grassmannian space.

RP3 is (diffeomorphic to) SO(3), hence admits a group structure; the covering map S3 → RP3 is a map of groups Spin(3) → SO(3), where Spin(3) is a Lie group that is the universal cover of SO(3).

3-torus

The 3-dimensional torus is the product of 3 circles. That is:

The 3-torus, T3 can be described as a quotient of R3 under integral shifts in any coordinate. That is, the 3-torus is R3 modulo the action of the integer lattice Z3 (with the action being taken as vector addition). Equivalently, the 3-torus is obtained from the 3-dimensional cube by gluing the opposite faces together.

A 3-torus in this sense is an example of a 3-dimensional compact manifold. It is also an example of a compact abelian Lie group. This follows from the fact that the unit circle is a compact abelian Lie group (when identified with the unit complex numbers with multiplication). Group multiplication on the torus is then defined by coordinate-wise multiplication.

Hyperbolic 3-space

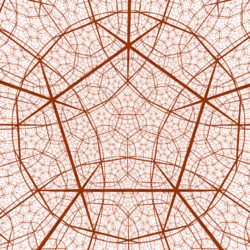

Four dodecahedra meet at each edge, and eight meet at each vertex, like the cubes of a cubic tessellation in E3

Hyperbolic space is a homogeneous space that can be characterized by a constant negative curvature. It is the model of hyperbolic geometry. It is distinguished from Euclidean spaces with zero curvature that define the Euclidean geometry, and models of elliptic geometry (like the 3-sphere) that have a constant positive curvature. When embedded to a Euclidean space (of a higher dimension), every point of a hyperbolic space is a saddle point. Another distinctive property is the amount of space covered by the 3-ball in hyperbolic 3-space: it increases exponentially with respect to the radius of the ball, rather than polynomially.

Poincaré dodecahedral space

The Poincaré homology sphere (also known as Poincaré dodecahedral space) is a particular example of a homology sphere. Being a spherical 3-manifold, it is the only homology 3-sphere (besides the 3-sphere itself) with a finite fundamental group. Its fundamental group is known as the binary icosahedral group and has order 120. This shows the Poincaré conjecture cannot be stated in homology terms alone.

In 2003, lack of structure on the largest scales (above 60 degrees) in the cosmic microwave background as observed for one year by the WMAP spacecraft led to the suggestion, by Jean-Pierre Luminet of the Observatoire de Paris and colleagues, that the shape of the universe is a Poincaré sphere.[4][5] In 2008, astronomers found the best orientation on the sky for the model and confirmed some of the predictions of the model, using three years of observations by the WMAP spacecraft.[6] However, there is no strong support for the correctness of the model, as yet.

Seifert–Weber space

In mathematics, Seifert–Weber space (introduced by Herbert Seifert and Constantin Weber) is a closed hyperbolic 3-manifold. It is also known as Seifert–Weber dodecahedral space and hyperbolic dodecahedral space. It is one of the first discovered examples of closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds.

It is constructed by gluing each face of a dodecahedron to its opposite in a way that produces a closed 3-manifold. There are three ways to do this gluing consistently. Opposite faces are misaligned by 1/10 of a turn, so to match them they must be rotated by 1/10, 3/10 or 5/10 turn; a rotation of 3/10 gives the Seifert–Weber space. Rotation of 1/10 gives the Poincaré homology sphere, and rotation by 5/10 gives 3-dimensional real projective space.

With the 3/10-turn gluing pattern, the edges of the original dodecahedron are glued to each other in groups of five. Thus, in the Seifert–Weber space, each edge is surrounded by five pentagonal faces, and the dihedral angle between these pentagons is 72°. This does not match the 117° dihedral angle of a regular dodecahedron in Euclidean space, but in hyperbolic space there exist regular dodecahedra with any dihedral angle between 60° and 117°, and the hyperbolic dodecahedron with dihedral angle 72° may be used to give the Seifert–Weber space a geometric structure as a hyperbolic manifold. It is a quotient space of the order-5 dodecahedral honeycomb, a regular tessellation of hyperbolic 3-space by dodecahedra with this dihedral angle.

Gieseking manifold

In mathematics, the Gieseking manifold is a cusped hyperbolic 3-manifold of finite volume. It is non-orientable and has the smallest volume among non-compact hyperbolic manifolds, having volume approximately 1.01494161. It was discovered by Hugo Gieseking (1912).

The Gieseking manifold can be constructed by removing the vertices from a tetrahedron, then gluing the faces together in pairs using affine-linear maps. Label the vertices 0, 1, 2, 3. Glue the face with vertices 0,1,2 to the face with vertices 3,1,0 in that order. Glue the face 0,2,3 to the face 3,2,1 in that order. In the hyperbolic structure of the Gieseking manifold, this ideal tetrahedron is the canonical polyhedral decomposition of David B. A. Epstein and Robert C. Penner.[7] Moreover, the angle made by the faces is . The triangulation has one tetrahedron, two faces, one edge and no vertices, so all the edges of the original tetrahedron are glued together.

Some important classes of 3-manifolds

- Graph manifold

- Haken manifold

- Homology spheres

- Hyperbolic 3-manifold

- I-bundles

- Knot and link complements

- Lens space

- Seifert fiber spaces, Circle bundles

- Spherical 3-manifold

- Surface bundles over the circle

- Torus bundle

Hyperbolic link complements

A hyperbolic link is a link in the 3-sphere with complement that has a complete Riemannian metric of constant negative curvature, i.e. has a hyperbolic geometry. A hyperbolic knot is a hyperbolic link with one component.

The following examples are particularly well-known and studied.

The classes are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

Some important structures on 3-manifolds

Contact geometry

Contact geometry is the study of a geometric structure on smooth manifolds given by a hyperplane distribution in the tangent bundle and specified by a one-form, both of which satisfy a 'maximum non-degeneracy' condition called 'complete non-integrability'. From the Frobenius theorem, one recognizes the condition as the opposite of the condition that the distribution be determined by a codimension one foliation on the manifold ('complete integrability').

Contact geometry is in many ways an odd-dimensional counterpart of symplectic geometry, which belongs to the even-dimensional world. Both contact and symplectic geometry are motivated by the mathematical formalism of classical mechanics, where one can consider either the even-dimensional phase space of a mechanical system or the odd-dimensional extended phase space that includes the time variable.

Haken manifold

A Haken manifold is a compact, P²-irreducible 3-manifold that is sufficiently large, meaning that it contains a properly embedded two-sided incompressible surface. Sometimes one considers only orientable Haken manifolds, in which case a Haken manifold is a compact, orientable, irreducible 3-manifold that contains an orientable, incompressible surface.

A 3-manifold finitely covered by a Haken manifold is said to be virtually Haken. The Virtually Haken conjecture asserts that every compact, irreducible 3-manifold with infinite fundamental group is virtually Haken.

Haken manifolds were introduced by Wolfgang Haken. Haken proved that Haken manifolds have a hierarchy, where they can be split up into 3-balls along incompressible surfaces. Haken also showed that there was a finite procedure to find an incompressible surface if the 3-manifold had one. Jaco and Oertel gave an algorithm to determine if a 3-manifold was Haken.

Essential lamination

An essential lamination is a lamination where every leaf is incompressible and end incompressible, if the complementary regions of the lamination are irreducible, and if there are no spherical leaves.

Essential laminations generalize the incompressible surfaces found in Haken manifolds.

Heegaard splitting

A Heegaard splitting is a decomposition of a compact oriented 3-manifold that results from dividing it into two handlebodies.

Every closed, orientable three-manifold may be so obtained; this follows from deep results on the triangulability of three-manifolds due to Moise. This contrasts strongly with higher-dimensional manifolds which need not admit smooth or piecewise linear structures. Assuming smoothness the existence of a Heegaard splitting also follows from the work of Smale about handle decompositions from Morse theory.

Taut foliation

A taut foliation is a codimension 1 foliation of a 3-manifold with the property that there is a single transverse circle intersecting every leaf. By transverse circle, is meant a closed loop that is always transverse to the tangent field of the foliation. Equivalently, by a result of Dennis Sullivan, a codimension 1 foliation is taut if there exists a Riemannian metric that makes each leaf a minimal surface.

Taut foliations were brought to prominence by the work of William Thurston and David Gabai.

Foundational results

Some results are named as conjectures as a result of historical artifacts.

We begin with the purely topological:

Moise's theorem

In geometric topology, Moise's theorem, proved by Edwin E. Moise in, states that any topological 3-manifold has an essentially unique piecewise-linear structure and smooth structure.

As corollary, every compact 3-manifold has a Heegaard splitting.

Prime decomposition theorem

The prime decomposition theorem for 3-manifolds states that every compact, orientable 3-manifold is the connected sum of a unique (up to homeomorphism) collection of prime 3-manifolds.

A manifold is prime if it cannot be presented as a connected sum of more than one manifold, none of which is the sphere of the same dimension.

Kneser–Haken finiteness

Kneser-Haken finiteness says that for each 3-manifold, there is a constant C such that any collection of surfaces of cardinality greater than C must contain parallel elements.

Loop and Sphere theorems

The loop theorem is a generalization of Dehn's lemma and should more properly be called the "disk theorem". It was first proven by Christos Papakyriakopoulos in 1956, along with Dehn's lemma and the Sphere theorem.

A simple and useful version of the loop theorem states that if there is a map

with not nullhomotopic in , then there is an embedding with the same property.

The sphere theorem of Papakyriakopoulos (1957) gives conditions for elements of the second homotopy group of a 3-manifold to be represented by embedded spheres.

One example is the following:

Let be an orientable 3-manifold such that is not the trivial group. Then there exists a non-zero element of having a representative that is an embedding .

Annulus and Torus theorems

The annulus theorem states that if a pair of disjoint simple closed curves on the boundary of a three manifold are freely homotopic then they cobound a properly embedded annulus. This should not be confused with the high dimensional theorem of the same name.

The torus theorem is as follows: Let M be a compact, irreducible 3-manifold with nonempty boundary. If M admits an essential map of a torus, then M admits an essential embedding of either a torus or an annulus[8]

JSJ decomposition

The JSJ decomposition, also known as the toral decomposition, is a topological construct given by the following theorem:

- Irreducible orientable closed (i.e., compact and without boundary) 3-manifolds have a unique (up to isotopy) minimal collection of disjointly embedded incompressible tori such that each component of the 3-manifold obtained by cutting along the tori is either atoroidal or Seifert-fibered.

The acronym JSJ is for William Jaco, Peter Shalen, and Klaus Johannson. The first two worked together, and the third worked independently.[9][10]

Scott core theorem

The Scott core theorem is a theorem about the finite presentability of fundamental groups of 3-manifolds due to G. Peter Scott.[11] The precise statement is as follows:

Given a 3-manifold (not necessarily compact) with finitely generated fundamental group, there is a compact three-dimensional submanifold, called the compact core or Scott core, such that its inclusion map induces an isomorphism on fundamental groups. In particular, this means a finitely generated 3-manifold group is finitely presentable.

A simplified proof is given in,[12] and a stronger uniqueness statement is proven in.[13]

Lickorish–Wallace theorem

The Lickorish–Wallace theorem states that any closed, orientable, connected 3-manifold may be obtained by performing Dehn surgery on a framed link in the 3-sphere with surgery coefficients. Furthermore, each component of the link can be assumed to be unknotted.

Waldhausen's theorems on topological rigidity

Friedhelm Waldhausen's theorems on topological rigidity say that certain 3-manifolds (such as those with an incompressible surface) are homeomorphic if there is an isomorphism of fundamental groups which respects the boundary.

Waldhausen conjecture on Heegaard splittings

Waldhausen conjectured that every closed orientable 3-manifold has only finitely many Heegaard splittings (up to homeomorphism) of any given genus.

Smith conjecture

The Smith conjecture (now proven) states that if f is a diffeomorphism of the 3-sphere of finite order, then the fixed point set of f cannot be a nontrivial knot.

Cyclic surgery theorem

The cyclic surgery theorem states that, for a compact, connected, orientable, irreducible three-manifold M whose boundary is a torus T, if M is not a Seifert-fibered space and r,s are slopes on T such that their Dehn fillings have cyclic fundamental group, then the distance between r and s (the minimal number of times that two simple closed curves in T representing r and s must intersect) is at most 1. Consequently, there are at most three Dehn fillings of M with cyclic fundamental group.

Thurston's hyperbolic Dehn surgery theorem and the Jørgensen–Thurston theorem

Thurston's hyperbolic Dehn surgery theorem states: is hyperbolic as long as a finite set of exceptional slopes is avoided for the i-th cusp for each i. In addition, converges to M in H as all for all corresponding to non-empty Dehn fillings .

This theorem is due to William Thurston and fundamental to the theory of hyperbolic 3-manifolds. It shows that nontrivial limits exist in H. Troels Jorgensen's study of the geometric topology further shows that all nontrivial limits arise by Dehn filling as in the theorem.

Another important result by Thurston is that volume decreases under hyperbolic Dehn filling. In fact, the theorem states that volume decreases under topological Dehn filling, assuming of course that the Dehn-filled manifold is hyperbolic. The proof relies on basic properties of the Gromov norm.

Jørgensen also showed that the volume function on this space is a continuous, proper function. Thus by the previous results, nontrivial limits in H are taken to nontrivial limits in the set of volumes. In fact, one can further conclude, as did Thurston, that the set of volumes of finite volume hyperbolic 3-manifolds has ordinal type . This result is known as the Thurston-Jørgensen theorem. Further work characterizing this set was done by Gromov.

Also, Gabai, Meyerhoff & Milley showed that the Weeks manifold has the smallest volume of any closed orientable hyperbolic 3-manifold.

Thurston's hyperbolization theorem for Haken manifolds

One form of Thurston's geometrization theorem states: If M is an compact irreducible atoroidal Haken manifold whose boundary has zero Euler characteristic, then the interior of M has a complete hyperbolic structure of finite volume.

The Mostow rigidity theorem implies that if a manifold of dimension at least 3 has a hyperbolic structure of finite volume, then it is essentially unique.

The conditions that the manifold M should be irreducible and atoroidal are necessary, as hyperbolic manifolds have these properties. However the condition that the manifold be Haken is unnecessarily strong. Thurston's hyperbolization conjecture states that a closed irreducible atoroidal 3-manifold with infinite fundamental group is hyperbolic, and this follows from Perelman's proof of the Thurston geometrization conjecture.

Tameness conjecture, also called the Marden conjecture or tame ends conjecture

The tameness theorem states that every complete hyperbolic 3-manifold with finitely generated fundamental group is topologically tame, in other words homeomorphic to the interior of a compact 3-manifold.

The tameness theorem was conjectured by Marden. It was proved by Agol and, independently, by Danny Calegari and David Gabai. It is one of the fundamental properties of geometrically infinite hyperbolic 3-manifolds, together with the density theorem for Kleinian groups and the ending lamination theorem. It also implies the Ahlfors measure conjecture.

Ending lamination conjecture

The ending lamination theorem, originally conjectured by William Thurston and later proven by Jeffrey Brock, Richard Canary, and Yair Minsky, states that hyperbolic 3-manifolds with finitely generated fundamental groups are determined by their topology together with certain "end invariants", which are geodesic laminations on some surfaces in the boundary of the manifold.

Poincaré conjecture

The 3-sphere is an especially important 3-manifold because of the now-proven Poincaré conjecture. Originally conjectured by Henri Poincaré, the theorem concerns a space that locally looks like ordinary three-dimensional space but is connected, finite in size, and lacks any boundary (a closed 3-manifold). The Poincaré conjecture claims that if such a space has the additional property that each loop in the space can be continuously tightened to a point, then it is necessarily a three-dimensional sphere. An analogous result has been known in higher dimensions for some time.

After nearly a century of effort by mathematicians, Grigori Perelman presented a proof of the conjecture in three papers made available in 2002 and 2003 on arXiv. The proof followed on from the program of Richard S. Hamilton to use the Ricci flow to attack the problem. Perelman introduced a modification of the standard Ricci flow, called Ricci flow with surgery to systematically excise singular regions as they develop, in a controlled way. Several teams of mathematicians have verified that Perelman's proof is correct.

Thurston's geometrization conjecture

Thurston's geometrization conjecture states that certain three-dimensional topological spaces each have a unique geometric structure that can be associated with them. It is an analogue of the uniformization theorem for two-dimensional surfaces, which states that every simply connected Riemann surface can be given one of three geometries (Euclidean, spherical, or hyperbolic). In three dimensions, it is not always possible to assign a single geometry to a whole topological space. Instead, the geometrization conjecture states that every closed 3-manifold can be decomposed in a canonical way into pieces that each have one of eight types of geometric structure. The conjecture was proposed by William (Thurston 1982), and implies several other conjectures, such as the Poincaré conjecture and Thurston's elliptization conjecture.

Thurston's hyperbolization theorem implies that Haken manifolds satisfy the geometrization conjecture. Thurston announced a proof in the 1980s and since then several complete proofs have appeared in print.

Grigori Perelman sketched a proof of the full geometrization conjecture in 2003 using Ricci flow with surgery. There are now several different manuscripts (see below) with details of the proof. The Poincaré conjecture and the spherical space form conjecture are corollaries of the geometrization conjecture, although there are shorter proofs of the former that do not lead to the geometrization conjecture.

Virtually fibered conjecture and Virtually Haken conjecture

The virtually fibered conjecture, formulated by United States mathematician William Thurston, states that every closed, irreducible, atoroidal 3-manifold with infinite fundamental group has a finite cover which is a surface bundle over the circle.

The virtually Haken conjecture states that every compact, orientable, irreducible three-dimensional manifold with infinite fundamental group is virtually Haken. That is, it has a finite cover (a covering space with a finite-to-one covering map) that is a Haken manifold.

In a posting on the ArXiv on 25 Aug 2009,[14] Daniel Wise implicitly implied (by referring to a then unpublished longer manuscript) that he had proven the Virtually fibered conjecture for the case where the 3-manifold is closed, hyperbolic, and Haken. This was followed by a survey article in Electronic Research Announcements in Mathematical Sciences.[15] Several more preprints[16] have followed, including the aforementioned longer manuscript by Wise.[17] In March 2012, during a conference at Institut Henri Poincaré in Paris, Ian Agol announced he could prove the virtually Haken conjecture for closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds.[18] The proof built on results of Kahn and Markovic[19][20] in their proof of the Surface subgroup conjecture and results of Wise in proving the Malnormal Special Quotient Theorem[17] and results of Bergeron and Wise for the cubulation of groups.[14] Taken together with Wise's results, this implies the virtually fibered conjecture for all closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds.

Simple loop conjecture

If is a map of closed connected surfaces such that is not injective, then there exists a non-contractible simple closed curve such that is homotopically trivial. This conjecture was proven by David Gabai.

Surface subgroup conjecture

The surface subgroup conjecture of Friedhelm Waldhausen states that the fundamental group of every closed, irreducible 3-manifold with infinite fundamental group has a surface subgroup. By "surface subgroup" we mean the fundamental group of a closed surface not the 2-sphere. This problem is listed as Problem 3.75 in Robion Kirby's problem list.[21]

Assuming the geometrization conjecture, the only open case was that of closed hyperbolic 3-manifolds. A proof of this case was announced in the Summer of 2009 by Jeremy Kahn and Vladimir Markovic and outlined in a talk August 4, 2009 at the FRG (Focused Research Group) Conference hosted by the University of Utah. A preprint appeared on the arxiv in October 2009.[22] Their paper was published in the Annals of Mathematics in 2012.[23] In June 2012, Kahn and Markovic were given the Clay Research Awards by the Clay Mathematics Institute at a ceremony in Oxford.[24]

Important conjectures

Cabling conjecture

The cabling conjecture states that if Dehn surgery on a knot in the 3-sphere yields a reducible 3-manifold, then that knot is a -cable on some other knot, and the surgery must have been performed using the slope .

Lubotzky–Sarnak conjecture

The fundamental group of any finite volume hyperbolic n-manifold does not have Property τ.

References

- ↑ Swarup, G. Ananda (1974). "On a Theorem of C. B. Thomas" (in en). Journal of the London Mathematical Society s2-8 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-8.1.13. ISSN 1469-7750. https://londmathsoc.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1112/jlms/s2-8.1.13.

- ↑ Swarup, G. Ananda (1973-06-01). "On embedded spheres in 3-manifolds" (in en). Mathematische Annalen 203 (2): 89–102. doi:10.1007/BF01431437. ISSN 1432-1807. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01431437.

- ↑ Zimmermann, Bruno. On the Classification of Finite Groups Acting on Homology 3-Spheres.

- ↑ "Is the universe a dodecahedron?", article at PhysicsWorld.

- ↑ Luminet, Jean-Pierre; Weeks, Jeffrey; Riazuelo, Alain; Lehoucq, Roland; Uzan, Jean-Phillipe (2003-10-09). "Dodecahedral space topology as an explanation for weak wide-angle temperature correlations in the cosmic microwave background". Nature 425 (6958): 593–595. doi:10.1038/nature01944. PMID 14534579. Bibcode: 2003Natur.425..593L.

- ↑ Roukema, Boudewijn; Zbigniew Buliński; Agnieszka Szaniewska; Nicolas E. Gaudin (2008). "A test of the Poincare dodecahedral space topology hypothesis with the WMAP CMB data". Astronomy and Astrophysics 482 (3): 747–753. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078777. Bibcode: 2008A&A...482..747L.

- ↑ Epstein, David B.A.; Penner, Robert C. (1988). "Euclidean decompositions of noncompact hyperbolic manifolds". Journal of Differential Geometry 27 (1): 67–80. doi:10.4310/jdg/1214441650.

- ↑ Feustel, Charles D (1976). "On the torus theorem and its applications". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 217: 1–43. doi:10.1090/s0002-9947-1976-0394666-3.

- ↑ Jaco, William; Shalen, Peter B. A new decomposition theorem for irreducible sufficiently-large 3-manifolds. Algebraic and geometric topology (Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., Stanford Univ., Stanford, Calif., 1976), Part 2, pp. 71–84, Proc. Sympos. Pure Math., XXXII, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, R.I., 1978.

- ↑ Johannson, Klaus, Homotopy equivalences of 3-manifolds with boundaries. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 761. Springer, Berlin, 1979. ISBN 3-540-09714-7

- ↑ Scott, G. Peter (1973), "Compact submanifolds of 3-manifolds", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series 7 (2): 246–250, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-7.2.246

- ↑ Rubinstein, J. Hyam; Swarup, Gadde A. (1990), "On Scott's core theorem", Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society 22 (5): 495–498, doi:10.1112/blms/22.5.495

- ↑ Harris, Luke; Scott, G. Peter (1996), "The uniqueness of compact cores for 3-manifolds", Pacific Journal of Mathematics 172 (1): 139–150, doi:10.2140/pjm.1996.172.139, http://projecteuclid.org/getRecord?id=euclid.pjm/1102366188

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Bergeron, Nicolas; Wise, Daniel T. (2009). "A boundary criterion for cubulation". arXiv:0908.3609 [math.GT].

- ↑ Wise, Daniel T. (2009-10-29), "Research announcement: The structure of groups with a quasiconvex hierarchy", Electronic Research Announcements in Mathematical Sciences 16: 44–55, doi:10.3934/era.2009.16.44, http://www.aimsciences.org/journals/displayArticles.jsp?paperID=4703

- ↑ Haglund and Wise, A combination theorem for special cube complexes,

Hruska and Wise, Finiteness properties of cubulated groups,

Hsu and Wise, Cubulating malnormal amalgams,

http://comet.lehman.cuny.edu/behrstock/cbms/program.html - ↑ 17.0 17.1 Daniel T. Wise, The structure of groups with a quasiconvex hierarchy, https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B45cNx80t5-2NTU0ZTdhMmItZTIxOS00ZGUyLWE0YzItNTEyYWFiMjczZmIz/edit?pli=1

- ↑ Agol, Ian; Groves, Daniel; Manning, Jason (2012). "The virtual Haken conjecture". arXiv:1204.2810 [math.GT].

- ↑ Kahn, Jeremy; Markovic, Vladimir (2009). "Immersing almost geodesic surfaces in a closed hyperbolic three manifold". arXiv:0910.5501 [math.GT].

- ↑ Kahn, Jeremy; Markovic, Vladimir (2010). "Counting Essential Surfaces in a Closed Hyperbolic 3-Manifold". arXiv:1012.2828 [math.GT].

- ↑ Robion Kirby, Problems in low-dimensional topology

- ↑ Kahn, Jeremy; Markovic, Vladimir (2009). "Immersing almost geodesic surfaces in a closed hyperbolic three manifold". arXiv:0910.5501 [math.GT].

- ↑ Kahn, Jeremy; Markovic, Vladimir (2012), "Immersing almost geodesic surfaces in a closed hyperbolic three manifold", Annals of Mathematics 175 (3): 1127–1190, doi:10.4007/annals.2012.175.3.4, http://annals.math.princeton.edu/2012/175-3/p04

- ↑ "2012 Clay Research Conference". http://www.claymath.org/research_conference/2012/.

Further reading

- Hempel, John (2004), 3-manifolds, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, doi:10.1090/chel/349, ISBN 0-8218-3695-1

- Jaco, William H. (1980), Lectures on three-manifold topology, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-1693-4

- Rolfsen, Dale (1976), Knots and Links, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-914098-16-0

- Thurston, William P. (1997), Three-dimensional geometry and topology, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08304-5

- Adams, Colin Conrad (2004), The Knot Book. An elementary introduction to the mathematical theory of knots. Revised reprint of the 1994 original., Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. xiv+307, ISBN 0-8050-7380-9

- Bing, R. H. (1983), The Geometric Topology of 3-Manifolds, Colloquium Publications, 40, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. x+238, ISBN 0-8218-1040-5

- Thurston, William P. (1982). "Three dimensional manifolds, Kleinian groups and hyperbolic geometry". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 6 (3): 357–382. doi:10.1090/s0273-0979-1982-15003-0. ISSN 0273-0979.

- Papakyriakopoulos, Christos D. (1957-01-15). "On Dehn's Lemma and the Asphericity of Knots". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 43 (1): 169–172. doi:10.1073/pnas.43.1.169. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 16589993. Bibcode: 1957PNAS...43..169P.

- "Topologische Fragen der Differentialgeometrie 43. Gewebe und Gruppen [31–32h]", Gesammelte Abhandlungen / Collected Papers, DE GRUYTER, 2005, doi:10.1515/9783110894516.239, ISBN 978-3-11-089451-6

External links

- Hatcher, Allen, Notes on basic 3-manifold topology, Cornell University, http://www.math.cornell.edu/~hatcher/3M/3Mdownloads.html

- Strickland, Neil, A Bestiary of Topological Objects

|

KSF

KSF