51 Pegasi

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

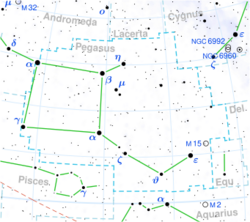

51 Pegasi (abbreviated 51 Peg), formally named Helvetios /hɛlˈviːʃiəs/,[12] is a Sun-like star located 50.6 light-years (15.5 parsecs) from Earth in the constellation of Pegasus. It was the first main-sequence star found to have an exoplanet (designated 51 Pegasi b, officially named Dimidium) orbiting it.[13]

Properties

The star's apparent magnitude is 5.49, making it visible with the naked eye under suitable viewing conditions.

51 Pegasi was listed as a standard star for the spectral type G2IV in the 1989 The Perkins catalog of revised MK types for the cooler stars. Historically, it was generally given a stellar classification of G5V,[14] and even in more modern catalogues it is usually listed as a main-sequence star.[15] The NStars project assign it a G2V spectral class.[4] It is generally considered to still be generating energy through the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen at its core, but to be in a more evolved state than the Sun.[3] The effective temperature of the chromosphere is about 5,571 K (5,298 °C; 9,568 °F), giving 51 Pegasi the characteristic yellow hue of a G-type star.[16] It is estimated to be about 4.8 billion years old, about the same age as the Sun, with a radius 11.5% larger and 9% more mass.[7] The star has a higher proportion of elements other than hydrogen/helium compared to the Sun; a quantity astronomers term a star's metallicity. Stars with higher metallicity such as this are more likely to host giant planets.[17] In 1996, astronomers Baliunas, Sokoloff, and Soon measured a rotational period of 37 days for 51 Pegasi.[18]

Although the star was suspected of being variable during a 1981 study,[19] subsequent observation showed there was almost no chromospheric activity between 1977 and 1989. Further examination between 1994 and 2007 showed a similar low or flat level of activity. This, along with its relatively low X-ray emission, suggests that the star may be in a Maunder minimum period[14] during which a star produces a reduced number of star spots.

The star rotates at an inclination of 79+11−30 degrees relative to Earth.[9]

Nomenclature

51 Pegasi is the Flamsteed designation. On its discovery, the star's planet — and actually the first exoplanet discovered around a main-sequence star — was designated 51 Pegasi b by its discoverers and unofficially dubbed Bellerophon, in keeping with the convention of naming planets after Greek and Roman mythological figures (Bellerophon was a figure from Greek mythology who rode the winged horse Pegasus).[20]

In July 2014, the International Astronomical Union launched NameExoWorlds, a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[21] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[22] In December 2015, the IAU announced the names of Helvetios for this star and Dimidium for its planet.[23]

The names were those submitted by the Astronomische Gesellschaft Luzern, Switzerland. "Helvetios" is Latin for "the Helvetian" and refers to the Celtic tribe that lived in Switzerland during antiquity; 'Dimidium' is Latin for 'half', referring to the planet's mass of at least half the mass of Jupiter.[24]

In 2016, the IAU organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[25] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. In its first bulletin of July 2016,[26] the WGSN explicitly recognized the names of exoplanets and their host stars approved by the Executive Committee Working Group Public Naming of Planets and Planetary Satellites, including the names of stars adopted during the 2015 NameExoWorlds campaign. This star is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[12]

Planetary system

On October 6, 1995, Swiss astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz announced the discovery of an exoplanet orbiting 51 Pegasi.[13] The discovery was made at Observatoire de Haute-Provence in France. On 8 October 2019, Mayor and Queloz shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery.[27]

51 Pegasi b (51 Peg b) was the first discovered exoplanet around a main-sequence star. It orbits very close to the star, experiences estimated temperatures around 1,200 °C (1,500 K; 2,200 °F) and has a mass at least half that of Jupiter. At the time of its discovery, this close distance was not compatible with theories of planet formation and resulted in discussions of planetary migration.[28] However, several hot Jupiters are now known to be oblique relative to the stellar axis.[29]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (Dimidium) | ≥ 0.472 ± 0.039 MJ | 0.0527 ± 0.0030 | 4.230785 ± 0.000036 | 0.013 ± 0.012 | — | 1.2±0.1[31] RJ |

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Vallenari, A. et al. (2022). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940 Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 van Belle, Gerard T.; von Braun, Kaspar (2009). "Directly Determined Linear Radii and Effective Temperatures of Exoplanet Host Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 694 (2): 1085–1098. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/1085. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...694.1085V.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Mittag, M.; Schröder, K.-P.; Hempelmann, A.; González-Pérez, J. N.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M. (2016). "Chromospheric activity and evolutionary age of the Sun and four solar twins". Astronomy & Astrophysics 591: A89. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527542. Bibcode: 2016A&A...591A..89M.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gray, R. O.; Corbally, C. J.; Garrison, R. F.; McFadden, M. T.; Bubar, E. J.; McGahee, C. E.; O'Donoghue, A. A.; Knox, E. R. (2006-07-01). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample". The Astronomical Journal 132 (1): 161–170. doi:10.1086/504637. ISSN 0004-6256. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..161G.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Monet, David G. et al. (February 2003). "The USNO-B Catalog". The Astronomical Journal 125 (2): 984–993. doi:10.1086/345888. Bibcode: 2003AJ....125..984M.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Johnson, H. L. et al. (1966). "UBVRIJKL photometry of the bright stars". Communications of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory 4 (99): 99. Bibcode: 1966CoLPL...4...99J.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Metcalfe, Travis S.; Strassmeier, Klaus G.; Ilyin, Ilya V.; Buzasi, Derek; Kochukhov, Oleg; Ayres, Thomas R.; Basu, Sarbani; Chontos, Ashley et al. (January 2024). "Weakened Magnetic Braking in the Exoplanet Host Star 51 Peg" (in en). The Astrophysical Journal Letters 960 (1): L6. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ad0a95. ISSN 2041-8205. Bibcode: 2024ApJ...960L...6M.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Soubiran, C.; Creevey, O. L.; Lagarde, N.; Brouillet, N.; Jofré, P.; Casamiquela, L.; Heiter, U.; Aguilera-Gómez, C. et al. (2024-02-01). "Gaia FGK benchmark stars: Fundamental Teff and log g of the third version". Astronomy and Astrophysics 682: A145. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347136. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2024A&A...682A.145S. 51 Pegasi's database entry at VizieR.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Simpson, E. K. et al. (November 2010). "Rotation periods of exoplanet host stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 408 (3): 1666–1679. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17230.x. Bibcode: 2010MNRAS.408.1666S. [as HD 217014]

- ↑ Rainer, M. et al. (2023). "The GAPS programme at TNG: XLIV. Projected rotational velocities of 273 exoplanet-host stars observed with HARPS-N". Astronomy & Astrophysics 676. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202245564. Bibcode: 2023A&A...676A..90R. Vizier catalog entry

- ↑ "51 Peg – Star suspected of Variability". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-id?Ident=51+Pegasi.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "IAU Catalog of Star Names". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/IAU-CSN.txt.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mayor, Michael; Queloz, Didier (1995). "A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star". Nature 378 (6555): 355–359. doi:10.1038/378355a0. Bibcode: 1995Natur.378..355M.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Poppenhäger, K. et al. (December 2009). "51 Pegasi – a planet-bearing Maunder minimum candidate". Astronomy and Astrophysics 508 (3): 1417–1421. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912945. Bibcode: 2009A&A...508.1417P.

- ↑ Skiff, B. A. (2014). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Spectral Classifications (Skiff, 2009–2016)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog. Bibcode: 2014yCat....1.2023S.

- ↑ "The Colour of Stars". Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. December 21, 2004. http://outreach.atnf.csiro.au/education/senior/astrophysics/photometry_colour.html.

- ↑ Buchhave, Lars A.; Latham, David W.; Johansen, Anders; Bizzarro, Martin; Torres, Guillermo; Rowe, Jason F.; Batalha, Natalie M.; Borucki, William J. et al. (June 2012). "An abundance of small exoplanets around stars with a wide range of metallicities" (in en). Nature 486 (7403): 375–377. doi:10.1038/nature11121. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 22722196. Bibcode: 2012Natur.486..375B. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature11121.

- ↑ Baliunas, Sallie; Sokoloff, Dmitry; Soon, Willie (1996). "Magnetic Field and Rotation in Lower Main-Sequence Stars: An Empirical Time-Dependent Magnetic Bode's Relation?". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 457 (2): L99–L102. doi:10.1086/309891. Bibcode: 1996ApJ...457L..99B.

- ↑ Kukarkin, B. V. et al. (1981). "Nachrichtenblatt der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde e.V. (Catalogue of suspected variable stars)". Nachrichtenblatt der Vereinigung der Sternfreunde: 0. Bibcode: 1981NVS...C......0K.

- ↑ "University of California at Berkeley News Release". 1996-11-17. http://www.berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/96legacy/releases.96/14301.html.

- ↑ "NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars]" (Press release). IAU. 9 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ "NameExoWorlds The Process". http://nameexoworlds.iau.org/process.

- ↑ "Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released]" (Press release). International Astronomical Union. 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-12-02. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ "NameExoWorlds The Approved Names". http://nameexoworlds.iau.org/names.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/WGSN_bulletin1.pdf.

- ↑ "Nobel prize for physics: exoplanets and cosmology". The Economist. 2019-10-08. ISSN 0013-0613. https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2019/10/08/nobel-prize-for-physics-exoplanets-and-cosmology.

- ↑ "51_peg_b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. 1995. https://exoplanet.eu/catalog/51_peg_b--12/. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ↑ Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda; Josh N. Winn; Daniel C. Fabrycky (2012). "Starspots and spin-orbit alignment for Kepler cool host stars". Astronomische Nachrichten 334 (1–2): 180. doi:10.1002/asna.201211765. Bibcode: 2013AN....334..180S.

- ↑ Butler, R. P. et al. (2006). "Catalog of Nearby Exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal 646 (1): 505–522. doi:10.1086/504701. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...646..505B.

- ↑ Spring, E. F.; Birkby, J. L.; Pino, L.; Alonso, R.; Hoyer, S.; Young, M. E.; Coelho, P. R. T.; Nespral, D. et al. (2022-03-01). "Black Mirror: The impact of rotational broadening on the search for reflected light from 51 Pegasi b with high resolution spectroscopy" (in en). Astronomy & Astrophysics 659: A121. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142314. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2022A&A...659A.121S. https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2022/03/aa42314-21/aa42314-21.html.

External links

- Jean Schneider (2011). "Notes for star 51 Peg". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. http://exoplanet.eu/star.php?st=51+Peg&showPubli=yes&sortByDate#a_publi. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- 51 Pegasi at SolStation.com.

- nStars database entry

- David Darling's encyclopedia

Coordinates: ![]() 22h 57m 28.0s, +20° 46′ 08″

22h 57m 28.0s, +20° 46′ 08″

|

KSF

KSF