Atmosphere of Mars

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 47 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 47 min

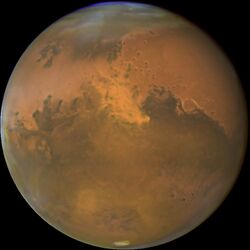

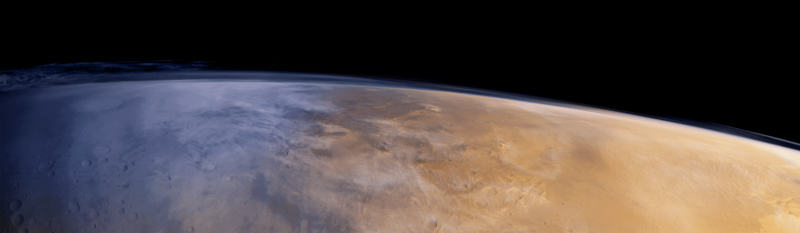

Template:AstronomicalAtmosphere The atmosphere of Mars is the layer of gases surrounding Mars. It is primarily composed of carbon dioxide (95%), molecular nitrogen (2.85%), and argon (2%).[1] It also contains trace levels of water vapor, oxygen, carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and noble gases.[1][2][3] The atmosphere of Mars is much thinner than Earth's. The average surface pressure is only about 610 pascals (0.088 psi) which is less than 1% of the Earth's value.[3]

The currently thin Martian atmosphere prohibits the existence of liquid water on the surface of Mars, but many studies suggest that the Martian atmosphere was much thicker in the past.[4] The higher density during spring and fall is reduced by 25% during the winter when carbon dioxide partly freezes at the pole caps.[5] The highest atmospheric density on Mars is equal to the density found 35 km (22 mi) above the Earth's surface and is ≈0.020 kg/m3.[6] The atmosphere of Mars has been losing mass to space since the planet's core slowed down, and the leakage of gases still continues today.[4][7][8]

The atmosphere of Mars is colder than Earth's. Owing to the larger distance from the Sun, Mars receives less solar energy and has a lower effective temperature, which is about 210 K (−63 °C; −82 °F).[3] The average surface emission temperature of Mars is just 215 K (−58 °C; −73 °F), which is comparable to inland Antarctica.[3][4] Although Mars' atmosphere consists primarily of carbon dioxide, the greenhouse effect in the Martian atmosphere is much weaker than Earth's: 5 °C (9.0 °F) on Mars, versus 33 °C (59 °F) on Earth. This is because the total atmosphere is so thin that the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is very weak, leading to less warming.[3][4] The daily range of temperature in the lower atmosphere presents ample variation due to the low thermal inertia; it can range from −75 °C (−103 °F) to near 0 °C (32 °F) near the surface in some regions.[3][4][9] The temperature of the upper part of the Martian atmosphere is also significantly lower than Earth's because of the absence of stratospheric ozone and the radiative cooling effect of carbon dioxide at higher altitudes.[4]

Dust devils and dust storms are prevalent on Mars, which are sometimes observable by telescopes from Earth,[10] and in 2018 even with the naked eye as a change in colour and brightness of the planet.[11] Planet-encircling dust storms (global dust storms) occur on average every 5.5 Earth years (every 3 Martian years) on Mars[4][10] and can threaten the operation of Mars rovers.[12] However, the mechanism responsible for the development of large dust storms is still not well understood.[13][14] It has been suggested to be loosely related to gravitational influence of both moons, somewhat similar to the creation of tides on Earth.

The Martian atmosphere is an oxidizing atmosphere. The photochemical reactions in the atmosphere tend to oxidize the organic species and turn them into carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide.[4] Although the most sensitive methane probe on the recently launched ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter failed to find methane in the atmosphere over the whole of Mars,[15][16][17] several previous missions and ground-based telescopes detected unexpected levels of methane in the Martian atmosphere, which may even be a biosignature for life on Mars.[18][19][20] However, the interpretation of the measurements is still highly controversial and lacks a scientific consensus.[20][21]

Atmospheric evolution

- The mass and composition of the Martian atmosphere are thought to have changed over the course of the planet's lifetime. A thicker, warmer and wetter atmosphere is required to explain several apparent features in the earlier history of Mars, such as the existence of liquid water bodies. Observations of the Martian upper atmosphere, measurements of isotopic composition and analyses of Martian meteorites, provide evidence of the long-term changes of the atmosphere and constraints for the relative importance of different processes.

Atmosphere in the early history

| Isotopic ratio | Mars | Earth | Mars / Earth |

|---|---|---|---|

| D / H (in H2O) | 9.3 ± 1.7 10-4[22][4] | 1.56 10-4[23] | ~6 |

| 12C / 13C | 85.1 ± 0.3[22][4] | 89.9[24] | 0.95 |

| 14N / 15N | 173 ± 9[22][25][4] | 272[23] | 0.64 |

| 16O / 18O | 476 ± 4.0[22][4] | 499[24] | 0.95 |

| 36Ar / 38Ar | 4.2 ± 0.1[26] | 5.305 ± 0.008[27] | 0.79 |

| 40Ar / 36Ar | 1900 ± 300[28] | 298.56 ± 0.31[27] | ~6 |

| C / 84Kr | (4.4–6) × 106[29][4] | 4 × 107[29][4] | ~0.1 |

| 129Xe / 132Xe | 2.5221 ± 0.0063[30] | 0.97[citation needed] | ~2.5 |

In general, the gases found on modern Mars are depleted in lighter stable isotopes, indicating the Martian atmosphere has changed by some mass-selected processes over its history. Scientists often rely on these measurements of isotope composition to reconstruct conditions of the Martian atmosphere in the past.[31][32][33]

While Mars and Earth have similar 12C / 13C and 16O / 18O ratios, 14N is much more depleted in the Martian atmosphere. It is thought that the photochemical escape processes are responsible for the isotopic fractionation and has caused a significant loss of nitrogen on geological timescales.[4] Estimates suggest that the initial partial pressure of N2 may have been up to 30 hPa.[34][35]

Hydrodynamic escape in the early history of Mars may explain the isotopic fractionation of argon and xenon. On modern Mars, the atmosphere is not leaking these two noble gases to outer space owing to their heavier mass. However, the higher abundance of hydrogen in the Martian atmosphere and the high fluxes of extreme UV from the young Sun, together could have driven a hydrodynamic outflow and dragged away these heavy gases.[36][37][4] Hydrodynamic escape also contributed to the loss of carbon, and models suggest that it is possible to lose 1,000 hPa (1 bar) of CO2 by hydrodynamic escape in one to ten million years under much stronger solar extreme UV on Mars.[38] Meanwhile, more recent observations made by the MAVEN orbiter suggested that sputtering escape is very important for the escape of heavy gases on the nightside of Mars and could have contributed to 65% loss of argon in the history of Mars.[39][40][32]

The Martian atmosphere is particularly prone to impact erosion owing to the low escape velocity of Mars. An early computer model suggested that Mars could have lost 99% of its initial atmosphere by the end of late heavy bombardment period based on a hypothetical bombardment flux estimated from lunar crater density.[41] In terms of relative abundance of carbon, the C / 84Kr ratio on Mars is only 10% of that on Earth and Venus. Assuming the three rocky planets have the same initial volatile inventory, then this low C / 84Kr ratio implies the mass of CO2 in the early Martian atmosphere should have been ten times higher than the present value.[42] The huge enrichment of radiogenic 40Ar over primordial 36Ar is also consistent with the impact erosion theory.[4]

One of the ways to estimate the amount of water lost by hydrogen escape in the upper atmosphere is to examine the enrichment of deuterium over hydrogen. Isotope-based studies estimate that 12 m to over 30 m global equivalent layer of water has been lost to space via hydrogen escape in Mars' history.[43] It is noted that atmospheric-escape-based approach only provides the lower limit for the estimated early water inventory.[4]

To explain the coexistence of liquid water and faint young Sun during early Mars' history, a much stronger greenhouse effect must have occurred in the Martian atmosphere to warm the surface up above freezing point of water. Carl Sagan first proposed that a 1 bar H2 atmosphere can produce enough warming for Mars.[44] The hydrogen can be produced by the vigorous outgassing from a highly reduced early Martian mantle and the presence of CO2 and water vapor can lower the required abundance of H2 to generate such a greenhouse effect.[45] Nevertheless, photochemical modeling showed that maintaining an atmosphere with this high level of H2 is difficult.[46] SO2 has also been one of the proposed effective greenhouse gases in the early history of Mars.[47][48][49] However, other studies suggested that high solubility of SO2, efficient formation of H2SO4 aerosol and surface deposition prohibit the long-term build-up of SO2 in the Martian atmosphere, and hence reduce the potential warming effect of SO2.[4]

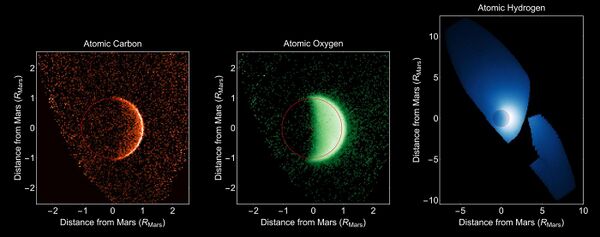

Atmospheric escape on modern Mars

Despite the lower gravity, Jeans escape is not efficient in the modern Martian atmosphere due to the relatively low temperature at the exobase (≈200 K at 200 km altitude). It can only explain the escape of hydrogen from Mars. Other non-thermal processes are needed to explain the observed escape of oxygen, carbon and nitrogen.

Hydrogen escape

Molecular hydrogen (H2) is produced from the dissociation of H2O or other hydrogen-containing compounds in the lower atmosphere and diffuses to the exosphere. The exospheric H2 then decomposes into hydrogen atoms, and the atoms that have sufficient thermal energy can escape from the gravitation of Mars (Jeans escape). The escape of atomic hydrogen is evident from the UV spectrometers on different orbiters.[50][51] While most studies suggested that the escape of hydrogen is close to diffusion-limited on Mars,[52][53] more recent studies suggest that the escape rate is modulated by dust storms and has a large seasonality.[54][55][56] The estimated escape flux of hydrogen range from 107 cm−2 s−1 to 109 cm−2 s−1.[55]

Carbon escape

Photochemistry of CO2 and CO in ionosphere can produce CO2+ and CO+ ions, respectively:

- CO

2 + hν ⟶ CO+

2 + e− - CO + hν ⟶ CO+

+ e−

An ion and an electron can recombine and produce electronic-neutral products. The products gain extra kinetic energy due to the Coulomb attraction between ions and electrons. This process is called dissociative recombination. Dissociative recombination can produce carbon atoms that travel faster than the escape velocity of Mars, and those moving upward can then escape the Martian atmosphere:

- CO+

+ e−

⟶ C + O - CO+

2 + e−

⟶ C + O

2

UV photolysis of carbon monoxide is another crucial mechanism for the carbon escape on Mars:[57]

- CO + hν (λ < 116 nm) ⟶ C + O.

Other potentially important mechanisms include the sputtering escape of CO2 and collision of carbon with fast oxygen atoms.[4] The estimated overall escape flux is about 0.6 × 107 cm−2 s−1 to 2.2 × 107 cm−2 s−1 and depends heavily on solar activity.[58][4]

Nitrogen escape

Like carbon, dissociative recombination of N2+ is important for the nitrogen escape on Mars.[59][60] In addition, other photochemical escape mechanism also play an important role:[59][61]

- N

2 + hν ⟶ N+

+ N + e− - N

2 + e−

⟶ N+

+ N + 2e−

Nitrogen escape rate is very sensitive to the mass of the atom and solar activity. The overall estimated escape rate of 14N is 4.8 × 105 cm−2 s−1.[59]

Oxygen escape

Dissociative recombination of CO2+ and O2+ (produced from CO2+ reaction as well) can generate the oxygen atoms that travel fast enough to escape:

- CO+

2 + e−

⟶ CO + O - CO+

2 + O ⟶ O+

2 + CO - O+

2 + e−

⟶ O + O

However, the observations showed that there are not enough fast oxygen atoms the Martian exosphere as predicted by the dissociative recombination mechanism.[62][40] Model estimations of oxygen escape rate suggested it can be over 10 times lower than the hydrogen escape rate.[58][63] Ion pick and sputtering have been suggested as the alternative mechanisms for the oxygen escape, but this model suggests that they are less important than dissociative recombination at present.[64]

Current chemical composition

Carbon dioxide

CO2 is the main component of the Martian atmosphere. It has a mean volume (molar) ratio of 94.9%.[1] In winter polar regions, the surface temperature can be lower than the frost point of CO2. CO2 gas in the atmosphere can condense on the surface to form 1–2 m thick solid dry ice.[4] In summer, the polar dry ice cap can undergo sublimation and release the CO2 back to the atmosphere. As a result, significant annual variability in atmospheric pressure (≈25%) and atmospheric composition can be observed on Mars.[66] The condensation process can be approximated by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation for CO2.[67][4]

There also exists the potential for adsorption of CO2 into and out of the regolith to contribute to the annual atmospheric variability. Although the sublimation and deposition of CO2 ice in the polar caps is the driving force behind seasonal cycles, other processes such as dust storms, atmospheric tides, and transient eddies also play a role.[68][69][70][71][72] Understanding each of these more minor processes and how they contribute to the overall atmospheric cycle will give a clearer picture as to how the Martian atmosphere works as a whole. It has been suggested that the regolith on Mars has high internal surface area, implying that it might have a relatively high capacity for the storage of adsorbed gas.[73] Since adsorption works through the adhesion of a film of molecules onto a surface, the amount of surface area for any given volume of material is the main contributor for how much adsorption can occur. A solid block of material, for example, would have no internal surface area, but a porous material, like a sponge, would have high internal surface area. Given the loose, finely grained nature of the Martian regolith, there is the possibility of significant levels of CO2 adsorption into it from the atmosphere.[74] Adsorption from the atmosphere into the regolith has previously been proposed as an explanation for the observed cycles in the methane and water mixing ratios.[73][74][75][76] More research is needed to help determine if CO2 adsorption is occurring, and if so, the extent of its impact on the overall atmospheric cycle.

Despite the high concentration of CO2 in the Martian atmosphere, the greenhouse effect is relatively weak on Mars (about 5 °C) because of the low concentration of water vapor and low atmospheric pressure. While water vapor in Earth's atmosphere has the largest contribution to greenhouse effect on modern Earth, it is present in only very low concentration in the Martian atmosphere. Moreover, under low atmospheric pressure, greenhouse gases cannot absorb infrared radiation effectively because the pressure-broadening effect is weak.[77][78]

In the presence of solar UV radiation (hν, photons with wavelength shorter than 225 nm), CO2 in the Martian atmosphere can be photolyzed via the following reaction:

- CO

2 + hν (λ < 225 nm) ⟶ CO + O.

If there is no chemical production of CO2, all the CO2 in the current Martian atmosphere would be removed by photolysis in about 3,500 years.[4] The hydroxyl radicals (OH) produced from the photolysis of water vapor, together with the other odd hydrogen species (e.g. H, HO2), can convert carbon monoxide (CO) back to CO2. The reaction cycle can be described as:[79][80]

- CO + OH ⟶ CO

2 + H - H + O

2 + M ⟶ HO

2 + M - HO

2 + O ⟶ OH + O

2 - Net: CO + O ⟶ CO

2

Mixing also plays a role in regenerating CO2 by bringing the O, CO, and O2 in the upper atmosphere downward.[4] The balance between photolysis and redox production keeps the average concentration of CO2 stable in the modern Martian atmosphere.

CO2 ice clouds can form in winter polar regions and at very high altitudes (>50 km) in tropical regions, where the air temperature is lower than the frost point of CO2.[3][81][82]

Nitrogen

N2 is the second most abundant gas in the Martian atmosphere. It has a mean volume ratio of 2.6%.[1] Various measurements showed that the Martian atmosphere is enriched in 15N.[83][34] The enrichment of heavy isotopes of nitrogen is possibly caused by mass-selective escape processes.[84]

Argon

Argon is the third most abundant gas in the Martian atmosphere. It has a mean volume ratio of 1.9%.[1] In terms of stable isotopes, Mars is enriched in 38Ar relative to 36Ar, which can be attributed to hydrodynamic escape.

One of Argon's isotopes, 40Ar, is produced from the radioactive decay of 40K. In contrast, 36Ar is primordial: It was present in the atmosphere after the formation of Mars. Observations indicate that Mars is enriched in 40Ar relative to 36Ar, which cannot be attributed to mass-selective loss processes.[28] A possible explanation for the enrichment is that a significant amount of primordial atmosphere, including 36Ar, was lost by impact erosion in the early history of Mars, while 40Ar was emitted to the atmosphere after the impact.[28][4]

Oxygen and ozone

The estimated mean volume ratio of molecular oxygen (O2) in the Martian atmosphere is 0.174%.[1] It is one of the products of the photolysis of CO2, water vapor, and ozone (O3). It can react with atomic oxygen (O) to re-form ozone (O3). In 2010, the Herschel Space Observatory detected molecular oxygen in the Martian atmosphere.[87]

Atomic oxygen is produced by photolysis of CO2 in the upper atmosphere and can escape the atmosphere via dissociative recombination or ion pickup. In early 2016, Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) detected atomic oxygen in the atmosphere of Mars, which has not been found since the Viking and Mariner mission in the 1970s.[88]

In 2019, NASA scientists working on the Curiosity rover mission, who have been taking measurements of the gas, discovered that the amount of oxygen in the Martian atmosphere rose by 30% in spring and summer.[89]

Similar to stratospheric ozone in Earth's atmosphere, the ozone present in the Martian atmosphere can be destroyed by catalytic cycles involving odd hydrogen species:

- H + O

3 ⟶ OH + O

2 - O + OH ⟶ H + O

2 - Net: O + O

3 ⟶ 2O

2

Since water is an important source of these odd hydrogen species, higher abundance of ozone is usually observed in the regions with lower water vapor content.[90] Measurements showed that the total column of ozone can reach 2–30 μm-atm around the poles in winter and spring, where the air is cold and has low water saturation ratio.[91] The actual reactions between ozone and odd hydrogen species may be further complicated by the heterogeneous reactions that take place in water-ice clouds.[92]

It is thought that the vertical distribution and seasonality of ozone in the Martian atmosphere is driven by the complex interactions between chemistry and transport of oxygen-rich air from sunlit latitudes to the poles.[93][94] The UV/IR spectrometer on Mars Express (SPICAM) has shown the presence of two distinct ozone layers at low-to-mid latitudes. These comprise a persistent, near-surface layer below an altitude of 30 km (19 mi), a separate layer that is only present in northern spring and summer with an altitude varying from 30 to 60 km, and another separate layer that exists 40–60 km above the southern pole in winter, with no counterpart above the Mars's north pole.[95] This third ozone layer shows an abrupt decrease in elevation between 75 and 50 degrees south. SPICAM detected a gradual increase in ozone concentration at 50 km (31 mi) until midwinter, after which it slowly decreased to very low concentrations, with no layer detectable above 35 km (22 mi).[93]

Water vapor

Water vapor is a trace gas in the Martian atmosphere and has huge spatial, diurnal and seasonal variability.[96][97] Measurements made by Viking orbiter in the late 1970s suggested that the entire global total mass of water vapor is equivalent to about 1 to 2 km3 of ice.[98] More recent measurements by Mars Express orbiter showed that the globally annually-averaged column abundance of water vapor is about 10-20 precipitable microns (pr. μm).[99][100] Maximum abundance of water vapor (50-70 pr. μm) is found in the northern polar regions in early summer due to the sublimation of water ice in the polar cap.[99]

Unlike in Earth's atmosphere, liquid-water clouds cannot exist in the Martian atmosphere; this is because of the low atmospheric pressure. Cirrus-like water-ice clouds have been observed by the cameras on Opportunity rover and Phoenix lander.[101][102] Measurements made by the Phoenix lander showed that water-ice clouds can form at the top of the planetary boundary layer at night and precipitate back to the surface as ice crystals in the northern polar region.[97][103]

thumb|Precipitated water ice covering the Martian plain [[Utopia Planitia, the water ice precipitated by adhering to dry ice (observed by the Viking 2 lander)]]

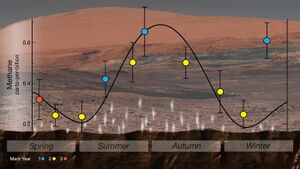

Methane

As a volcanic and biogenic species, methane is of interest to geologists and astrobiologists.[20] However, methane is chemically unstable in an oxidizing atmosphere with UV radiation. The lifetime of methane in the Martian atmosphere is about 400 years.[104] The detection of methane in a planetary atmosphere may indicate the presence of recent geological activities or living organisms.[20][105][106][104] Since 2004, trace amounts of methane (range from 60 ppb to under detection limit (< 0.05 ppb)) have been reported in various missions and observational studies.[107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][15] The source of methane on Mars and the explanation for the enormous discrepancy in the observed methane concentrations are still under active debate.[21][20][104]

See also the section "detection of methane in the atmosphere" for more details.

Sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) in the atmosphere would be an indicator of current volcanic activity. It has become especially interesting due to the long-standing controversy of methane on Mars. If volcanoes have been active in recent Martian history, it would be expected to find SO2 together with methane in the current Martian atmosphere.[116][117] No SO2 has been detected in the atmosphere, with a sensitivity upper limit set at 0.2 ppb.[118][119] However, a team led by scientists at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center reported detection of SO2 in Rocknest soil samples analyzed by the Curiosity rover in March 2013.[120]

Other trace gases

Carbon monoxide (CO) is produced by the photolysis of CO2 and quickly reacts with the oxidants in the Martian atmosphere to re-form CO2. The estimated mean volume ratio of CO in the Martian atmosphere is 0.0747%.[1]

Noble gases, other than helium and argon, are present at trace levels (neon at 2.5 ppmv, krypton at 0.3 ppmv and xenon at 0.08 ppmv[2]) in the Martian atmosphere. The concentration of helium, neon, krypton and xenon in the Martian atmosphere has been measured by different missions.[121][122][123][30] The isotopic ratios of noble gases reveal information about the early geological activities on Mars and the evolution of its atmosphere.[121][30][124]

Molecular hydrogen (H2) is produced by the reaction between odd hydrogen species in the middle atmosphere. It can be delivered to the upper atmosphere by mixing or diffusion, decompose to atomic hydrogen (H) by solar radiation and escape the Martian atmosphere.[125] Photochemical modeling estimated that the mixing ratio of H2 in the lower atmosphere is about 15 ±5 ppmv.[125]

Vertical structure

The vertical temperature structure of the Martian atmosphere differs from Earth's atmosphere in many ways. Information about the vertical structure is usually inferred by using the observations from thermal infrared soundings, radio occultation, aerobraking, landers' entry profiles.[126][127] Mars's atmosphere can be classified into three layers according to the average temperature profile:

- Troposphere (≈0–40 km): The layer where most of the weather phenomena (e.g. convection and dust storms) take place. Its dynamics is heavily driven by the daytime surface heating and the amount of suspended dust. Mars has a higher scale height of 11.1 km than Earth (8.5 km) because of its weaker gravity.[2] The theoretical dry adiabatic lapse rate of Mars is 4.3 °C km−1,[128] but the measured average lapse rate is about 2.5 °C km−1 because the suspended dust particles absorb solar radiation and heat the air.[3] The planetary boundary layer can extend to over 10 km thick during the daytime.[3][129] The near-surface diurnal temperature range is huge (60 °C[128]) due to the low thermal inertia. Under dusty conditions, the suspended dust particles can reduce the surface diurnal temperature range to only 5 °C.[130] The temperature above 15 km is controlled by radiative processes instead of convection.[3] Mars is also a rare exception to the "0.1-bar tropopause" rule found in the other atmospheres in our solar system.[131]

- Mesosphere (≈40–100 km): The layer that has the lowest temperature. CO2 in the mesosphere acts as a cooling agent by efficiently radiating heat into space. Stellar occultation observations show that the mesopause of Mars locates at about 100 km (around 0.01 to 0.001 Pa level) and has a temperature of 100-120 K.[132] The temperature can sometimes be lower than the frost point of CO2, and detections of CO2 ice clouds in the Martian mesosphere have been reported.[81][82]

- Thermosphere (≈100–230 km): The layer is mainly controlled by extreme UV heating. The temperature of the Martian thermosphere increases with altitude and varies by season. The daytime temperature of the upper thermosphere ranges from 175 K (at aphelion) to 240 K (at perihelion) and can reach up to 390 K,[133][134] but it is still significantly lower than the temperature of Earth's thermosphere. The higher concentration of CO2 in the Martian thermosphere may explain part of the discrepancy because of the cooling effects of CO2 in high altitude. It is thought that auroral heating processes is not important in the Martian thermosphere because of the absence of a strong magnetic field in Mars, but the MAVEN orbiter has detected several aurora events.[135][136]

Mars does not have a persistent stratosphere due to the lack of shortwave-absorbing species in its middle atmosphere (e.g. stratospheric ozone in Earth's atmosphere and organic haze in Jupiter's atmosphere) for creating a temperature inversion.[137] However, a seasonal ozone layer and a strong temperature inversion in the middle atmosphere have been observed over the Martian south pole.[94][138] The altitude of the turbopause of Mars varies greatly from 60 to 140 km, and the variability is driven by the CO2 density in the lower thermosphere.[139] Mars also has a complicated ionosphere that interacts with the solar wind particles, extreme UV radiation and X-rays from Sun, and the magnetic field of its crust.[140][141] The exosphere of Mars starts at about 230 km and gradually merges with interplanetary space.[3]File:Solar Wind Strips the Martian Atmosphere.webm

Atmospheric dust and other dynamic features

Atmospheric dust

- Under sufficiently strong wind (> 30 ms−1), dust particles can be mobilized and lifted from the surface to the atmosphere.[3][4] Some of the dust particles can be suspended in the atmosphere and travel by circulation before falling back to the ground.[13] Dust particles can attenuate solar radiation and interact with infrared radiation, which can lead to a significant radiative effect on Mars. Orbiter measurements suggest that the globally-averaged dust optical depth has a background level of 0.15 and peaks in the perihelion season (southern spring and summer).[142] The local abundance of dust varies greatly by seasons and years.[142][143] During global dust events, Mars surface assets can observe optical depth that is over 4.[144][145] Surface measurements also showed the effective radius of dust particles ranges from 0.6 μm to 2 μm and has considerable seasonality.[145][146][147]

Dust has an uneven vertical distribution on Mars. Apart from the planetary boundary layer, sounding data showed that there are other peaks of dust mixing ratio at the higher altitude (e.g. 15–30 km above the surface).[148][149][13]

Dust storms

Local and regional dust storms are not rare on Mars.[13][3] Local storms have a size of about 103 km2 and occurrence of about 2000 events per Martian year, while regional storms of 106 km2 large are observed frequently in southern spring and summer.[3] Near the polar cap, dust storms sometimes can be generated by frontal activities and extra-tropical cyclones.[150][13]

Global dust storms (area > 106 km2 ) occur on average once every 3 Martian years.[4] Observations showed that larger dust storms are usually the result of merging smaller dust storms,[10][14] but the growth mechanism of the storm and the role of atmospheric feedbacks are still not well understood.[14][13] Although it is thought that Martian dust can be entrained into the atmosphere by processes similar to Earth's (e.g. saltation), the actual mechanisms are yet to be verified, and electrostatic or magnetic forces may also play in modulating dust emission.[13] Researchers reported that the largest single source of dust on Mars comes from the Medusae Fossae Formation.[151]

On 1 June 2018, NASA scientists detected signs of a dust storm (see image) on Mars which resulted in the end of the solar-powered Opportunity rover's mission since the dust blocked the sunlight (see image) needed to operate. By 12 June, the storm was the most extensive recorded at the surface of the planet, and spanned an area about the size of North America and Russia combined (about a quarter of the planet). By 13 June, Opportunity rover began experiencing serious communication problems due to the dust storm.[152][153][154][155][156] File:PIA22737-Mars-2018DustStorm-MCS-MRO-Animation-20181030.webm

Dust devils

Dust devils are common on Mars.[157][13] Like their counterparts on Earth, dust devils form when the convective vortices driven by strong surface heating are loaded with dust particles.[158][159] Dust devils on Mars usually have a diameter of tens of meter and height of several kilometers, which are much taller than the ones observed on Earth.[3][159] Study of dust devils' tracks showed that most of Martian dust devils occur at around 60°N and 60°S in spring and summer.[157] They lift about 2.3 × 1011 kg of dust from land surface to atmosphere annually, which is comparable to the contribution from local and regional dust storms.[157]

Wind modification of the surface

On Mars, the near-surface wind is not only emitting dust but also modifying the geomorphology of Mars over long time scales. Although it was thought that the atmosphere of Mars is too thin for mobilizing the sandy features, observations made by HiRSE showed that the migration of dunes is not rare on Mars.[160][161][162] The global average migration rate of dunes (2 – 120 m tall) is about 0.5 meter per year.[162] Atmospheric circulation models suggested repeated cycles of wind erosion and dust deposition can lead, possibly, to a net transport of soil materials from the lowlands to the uplands on geological timescales.[4]

Thermal tides

- Solar heating on the day side and radiative cooling on the night side of a planet can induce pressure difference.[163] Thermal tides, which are the wind circulation and waves driven by such a daily-varying pressure field, can explain a lot of variability of the Martian atmosphere.[164] Compared to Earth's atmosphere, thermal tides have a larger influence on the Martian atmosphere because of the stronger diurnal temperature contrast.[165] The surface pressure measured by Mars rovers showed clear signals of thermal tides, although the variation also depends on the shape of the planet's surface and the amount of suspended dust in the atmosphere.[166] The atmospheric waves can also travel vertically and affect the temperature and water-ice content in the middle atmosphere of Mars.[164]

Orographic clouds

On Earth, mountain ranges sometimes force an air mass to rise and cool down. As a result, water vapor becomes saturated and clouds are formed during the lifting process.[167] On Mars, orbiters have observed a seasonally recurrent formation of huge water-ice clouds around the downwind side of the 20 km-high volcanoes Arsia Mons, which is likely caused by the same mechanism.[168][169]

Acoustic environment

File:NASA-SoundsOnMars-PerseveranceRover-20220401.webm In April 2022, scientists reported, for the first time, studies of sound waves on Mars. These studies were based on measurements by instruments on the Perseverance rover. The scientists found that the speed of sound is slower in the thin Martian atmosphere than on Earth. The speed of sound on Mars, within the audible bandwidth between 20 Hz - 20 kHz, varies depending on pitch, seemingly due to the low pressure and thermal turbulence of Martian surface air; and, as a result of these conditions, sound is much quieter, and live music would be more variable, than on Earth.[170][171][172]

Unexplained phenomena

Detection of methane

- Methane (CH4) is chemically unstable in the current oxidizing atmosphere of Mars. It would quickly break down due to ultraviolet radiation from the Sun and chemical reactions with other gases. Therefore, a persistent presence of methane in the atmosphere may imply the existence of a source to continually replenish the gas.

The ESA-Roscomos Trace Gas Orbiter, which has made the most sensitive measurements of methane in Mars' atmosphere with over 100 global soundings, has found no methane to a detection limit of 0.05 parts per billion (ppb).[15][16][17] However, there have been other reports of detection of methane by ground-based telescopes and Curiosity rover. Trace amounts of methane, at the level of several ppb, were first reported in Mars's atmosphere by a team at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in 2003.[173][174] Large differences in the abundances were measured between observations taken in 2003 and 2006, which suggested that the methane was locally concentrated and probably seasonal.[175]

In 2014, NASA reported that the Curiosity rover detected a tenfold increase ('spike') in methane in the atmosphere around it in late 2013 and early 2014. Four measurements taken over two months in this period averaged 7.2 ppb, implying that Mars is episodically producing or releasing methane from an unknown source.[113] Before and after that, readings averaged around one-tenth that level.[176][177][113] On 7 June 2018, NASA announced a cyclical seasonal variation in the background level of atmospheric methane.[178][19][179]

The principal candidates for the origin of Mars' methane include non-biological processes such as water-rock reactions, radiolysis of water, and pyrite formation, all of which produce H2 that could then generate methane and other hydrocarbons via Fischer–Tropsch synthesis with CO and CO2.[180] It has also been shown that methane could be produced by a process involving water, carbon dioxide, and the mineral olivine, which is known to be common on Mars.[181] Living microorganisms, such as methanogens, are another possible source, but no evidence for the presence of such organisms has been found on Mars.[182][183][108] There are some suspicions about the detection of methane, which suggests that it may instead be caused by the undocumented terrestrial contamination from the rovers or a misinterpretation of measurement raw data.[21][184]

Lightning events

In 2009, an Earth-based observational study reported detection of large-scale electric discharge events on Mars and proposed that they are related to lightning discharge in Martian dust storms.[185] However, later observation studies showed that the result is not reproducible using the radar receiver on Mars Express and the Earth-based Allen Telescope Array.[186][187][188] A laboratory study showed that the air pressure on Mars is not favorable for charging the dust grains, and thus it is difficult to generate lightning in Martian atmosphere.[189][188]

Super-rotating jet over the equator

Super-rotation refers to the phenomenon that atmospheric mass has a higher angular velocity than the surface of the planet at the equator, which in principle cannot be driven by inviscid axisymmetric circulations.[190][191] Assimilated data and general circulation model (GCM) simulation suggest that super-rotating jet can be found in Martian atmosphere during global dust storms, but it is much weaker than the ones observed on slow-rotating planets like Venus and Titan.[150] GCM experiments showed that the thermal tides can play a role in inducing the super-rotating jet.[192] Nevertheless, modeling super-rotation still remains as a challenging topic for planetary scientists.[191]

History of atmospheric observations

In 1784, German-born British astronomer William Herschel published an article about his observations of the Martian atmosphere in Philosophical Transactions and noted the occasional movement of a brighter region on Mars, which he attributed to clouds and vapors.[165][193] In 1809, French astronomer Honoré Flaugergues wrote about his observation of "yellow clouds" on Mars, which are likely to be dust storm events.[165] In 1864, William Rutter Dawes observed that "the ruddy tint of the planet does not arise from any peculiarity of its atmosphere; it seems to be fully proved by the fact that the redness is always deepest near the centre, where the atmosphere is thinnest."[194] Spectroscopic observations in the 1860s and 1870s[195] led many to think the atmosphere of Mars is similar to Earth's. In 1894, though, spectral analysis and other qualitative observations by William Wallace Campbell suggested Mars resembles the Moon, which has no appreciable atmosphere, in many respects.[195] In 1926, photographic observations by William Hammond Wright at the Lick Observatory allowed Donald Howard Menzel to discover quantitative evidence of Mars's atmosphere.[196][197]

With an enhanced understanding of optical properties of atmospheric gases and advancement in spectrometer technology, scientists started to measure the composition of the Martian atmosphere in the mid-20th century. Lewis David Kaplan and his team detected the signals of water vapor and carbon dioxide in the spectrogram of Mars in 1964,[198] as well as carbon monoxide in 1969.[199] In 1965, the measurements made during Mariner 4's flyby confirmed that the Martian atmosphere is constituted mostly of carbon dioxide, and the surface pressure is about 400 to 700 Pa.[200] After the composition of the Martian atmosphere was known, astrobiological research began on Earth to determine the viability of life on Mars. Containers that simulated environmental conditions on Mars, called "Mars jars", were developed for this purpose.[201]

In 1976, two landers of the Viking program provided the first ever in-situ measurements of the composition of the Martian atmosphere. Another objective of the mission included investigations for evidence of past or present life on Mars (see Viking lander biological experiments).[202] Since then, many orbiters and landers have been sent to Mars to measure different properties of the Martian atmosphere, such as concentration of trace gases and isotopic ratios. In addition, telescopic observations and analysis of Martian meteorites provide independent sources of information to verify the findings. The imageries and measurements made by these spacecraft greatly improve our understanding of the atmospheric processes outside Earth. The rover Curiosity and the lander InSight are still operating on the surface of Mars to carry out experiments and report the local daily weather.[203][204] The rover Perseverance and helicopter Ingenuity, which formed the Mars 2020 program, landed in February 2021. The rover Rosalind Franklin is scheduled to launch in 2022.

Potential for use by humans

The atmosphere of Mars is a resource of known composition available at any landing site on Mars. It has been proposed that human exploration of Mars could use carbon dioxide (CO2) from the Martian atmosphere to make methane (CH4) and use it as rocket fuel for the return mission. Mission studies that propose using the atmosphere in this way include the Mars Direct proposal of Robert Zubrin and the NASA Design Reference Mission study. Two major chemical pathways for use of the carbon dioxide are the Sabatier reaction, converting atmospheric carbon dioxide along with additional hydrogen (H2) to produce methane (CH4) and oxygen (O2), and electrolysis, using a zirconia solid oxide electrolyte to split the carbon dioxide into oxygen (O2) and carbon monoxide (CO).[205]

In 2021, however, the NASA rover Perseverance was able to make oxygen on Mars. The process is complex and takes a lot of time to produce a small amount of oxygen.[206]

Image gallery

See also

- Climate of Mars

- In situ resource utilization

- Life on Mars

- Mars MetNet

- Mars regional atmospheric modeling system

- MAVEN

- Seasonal flows on warm Martian slopes

- Terraforming of Mars

- Mars carbonate catastrophe

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Franz, Heather B.; Trainer, Melissa G.; Malespin, Charles A.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Atreya, Sushil K.; Becker, Richard H.; Benna, Mehdi; Conrad, Pamela G. et al. (2017-04-01). "Initial SAM calibration gas experiments on Mars: Quadrupole mass spectrometer results and implications". Planetary and Space Science 138: 44–54. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2017.01.014. ISSN 0032-0633. Bibcode: 2017P&SS..138...44F.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Mars Fact Sheet". https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/marsfact.html.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Haberle, R. M. (2015-01-01), North, Gerald R.; Pyle, John; Zhang, Fuqing, eds., SOLAR SYSTEM/SUN, ATMOSPHERES, EVOLUTION OF ATMOSPHERES | Planetary Atmospheres: Mars, Academic Press, pp. 168–177, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-382225-3.00312-1, ISBN 9780123822253

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 Catling, David C. (2017). Atmospheric evolution on inhabited and lifeless worlds. Kasting, James F.. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521844123. OCLC 956434982. Bibcode: 2017aeil.book.....C.

- ↑ "Weather, Weather, Everywhere?". http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/scitech/display.cfm?ST_ID=725.

- ↑ "Mars Fact Sheet". https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/marsfact.html.

- ↑ Jakosky, B. M.; Brain, D.; Chaffin, M.; Curry, S.; Deighan, J.; Grebowsky, J.; Halekas, J.; Leblanc, F. et al. (2018-11-15). "Loss of the Martian atmosphere to space: Present-day loss rates determined from MAVEN observations and integrated loss through time". Icarus 315: 146–157. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.05.030. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2018Icar..315..146J.

- ↑ mars.nasa.gov. "NASA's MAVEN Reveals Most of Mars' Atmosphere Was Lost to Space" (in en). https://mars.nasa.gov/news/1976/nasas-maven-reveals-most-of-mars-atmosphere-was-lost-to-space.

- ↑ "Temperature extremes on Mars" (in en-us). https://phys.org/news/2012-09-temperature-extremes-mars.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Hille, Karl (2015-09-18). "The Fact and Fiction of Martian Dust Storms". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/the-fact-and-fiction-of-martian-dust-storms.

- ↑ https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/is-the-mars-opposition-already-over/[Normally reddish-orange or even pink, Mars now glows pumpkin-orange. Even my eyes can see the difference. ALPO assistant coordinator Richard Schmude has also noted an increase in brightness of ≈0.2 magnitude concurrent with the color change.]

- ↑ Greicius, Tony (2018-06-08). "Opportunity Hunkers Down During Dust Storm". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/opportunity-hunkers-down-during-dust-storm.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Kok, Jasper F; Parteli, Eric J R; Michaels, Timothy I; Karam, Diana Bou (2012-09-14). "The physics of wind-blown sand and dust". Reports on Progress in Physics 75 (10): 106901. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/75/10/106901. ISSN 0034-4885. PMID 22982806. Bibcode: 2012RPPh...75j6901K.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Toigo, Anthony D.; Richardson, Mark I.; Wang, Huiqun; Guzewich, Scott D.; Newman, Claire E. (2018-03-01). "The cascade from local to global dust storms on Mars: Temporal and spatial thresholds on thermal and dynamical feedback". Icarus 302: 514–536. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2017.11.032. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2018Icar..302..514T.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Vago, Jorge L.; Svedhem, Håkan; Zelenyi, Lev; Etiope, Giuseppe; Wilson, Colin F.; López-Moreno, Jose-Juan; Bellucci, Giancarlo; Patel, Manish R. et al. (April 2019). "No detection of methane on Mars from early ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter observations". Nature 568 (7753): 517–520. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1096-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 30971829. Bibcode: 2019Natur.568..517K. http://oro.open.ac.uk/60547/2/2019%20Korablev%20TGO%20methane%20Nature_accepted.pdf. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 esa. "First results from the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter". http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/Exploration/ExoMars/First_results_from_the_ExoMars_Trace_Gas_Orbiter.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Weule, Genelle (2019-04-11). "Mars methane mystery thickens as newest probe fails to find the gas" (in en-AU). https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2019-04-11/mars-methane-atmosphere-exomars-trace-gas-orbiter/10972414.

- ↑ Formisano, Vittorio; Atreya, Sushil; Encrenaz, Thérèse; Ignatiev, Nikolai; Giuranna, Marco (2004-12-03). "Detection of Methane in the Atmosphere of Mars" (in en). Science 306 (5702): 1758–1761. doi:10.1126/science.1101732. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15514118. Bibcode: 2004Sci...306.1758F.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Webster, Christopher R. (8 June 2018). "Background levels of methane in Mars' atmosphere show strong seasonal variations". Science 360 (6393): 1093–1096. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131. PMID 29880682. Bibcode: 2018Sci...360.1093W.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Yung, Yuk L.; Chen, Pin; Nealson, Kenneth; Atreya, Sushil; Beckett, Patrick; Blank, Jennifer G.; Ehlmann, Bethany; Eiler, John et al. (2018-09-19). "Methane on Mars and Habitability: Challenges and Responses". Astrobiology 18 (10): 1221–1242. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1917. ISSN 1531-1074. PMID 30234380. Bibcode: 2018AsBio..18.1221Y.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Zahnle, Kevin; Freedman, Richard S.; Catling, David C. (2011-04-01). "Is there methane on Mars?". Icarus 212 (2): 493–503. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.11.027. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2011Icar..212..493Z. https://zenodo.org/record/1259041. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Mahaffy, P.R.; Conrad, P.G.; MSL Science Team (2015-02-01). "Volatile and Isotopic Imprints of Ancient Mars". Elements 11 (1): 51–56. doi:10.2113/gselements.11.1.51. ISSN 1811-5209.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Marty, Bernard (2012-01-01). "The origins and concentrations of water, carbon, nitrogen and noble gases on Earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 313–314: 56–66. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.10.040. ISSN 0012-821X. Bibcode: 2012E&PSL.313...56M.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Henderson, Paul (2009). The Cambridge Handbook of Earth Science Data. Henderson, Gideon. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511580925. OCLC 435778559.

- ↑ Wong, Michael H.; Atreya, Sushil K.; Mahaffy, Paul N.; Franz, Heather B.; Malespin, Charles; Trainer, Melissa G.; Stern, Jennifer C.; Conrad, Pamela G. et al. (2013-12-16). "Isotopes of nitrogen on Mars: Atmospheric measurements by Curiosity's mass spectrometer". Geophysical Research Letters. Mars atmospheric nitrogen isotopes 40 (23): 6033–6037. doi:10.1002/2013GL057840. PMID 26074632. Bibcode: 2013GeoRL..40.6033W.

- ↑ Atreya, Sushil K.; Trainer, Melissa G.; Franz, Heather B.; Wong, Michael H.; Manning, Heidi L.K.; Malespin, Charles A.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Conrad, Pamela G. et al. (2013). "Primordial argon isotope fractionation in the atmosphere of Mars measured by the SAM instrument on Curiosity and implications for atmospheric loss". Geophysical Research Letters 40 (21): 5605–5609. doi:10.1002/2013GL057763. ISSN 1944-8007. PMID 25821261. Bibcode: 2013GeoRL..40.5605A.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Lee, Jee-Yon; Marti, Kurt; Severinghaus, Jeffrey P.; Kawamura, Kenji; Yoo, Hee-Soo; Lee, Jin Bok; Kim, Jin Seog (2006-09-01). "A redetermination of the isotopic abundances of atmospheric Ar". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 70 (17): 4507–4512. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2006.06.1563. ISSN 0016-7037. Bibcode: 2006GeCoA..70.4507L.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Mahaffy, P.R.; Webster, C.R.; Atreya, S.K.; Franz, H.; Wong, M.; Conrad, P.G.; Harpold, D.; Jones, J.J. et al. (2013-07-19). "Abundance and isotopic composition of gases in the Martian atmosphere from the Curiosity rover". Science 341 (6143): 263–266. doi:10.1126/science.1237966. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 23869014. Bibcode: 2013Sci...341..263M.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Pepin, Robert O. (1991-07-01). "On the origin and early evolution of terrestrial planet atmospheres and meteoritic volatiles". Icarus 92 (1): 2–79. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(91)90036-S. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 1991Icar...92....2P.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Conrad, P. G.; Malespin, C. A.; Franz, H. B.; Pepin, R. O.; Trainer, M. G.; Schwenzer, S. P.; Atreya, S. K.; Freissinet, C. et al. (2016-11-15). "In situ measurement of atmospheric krypton and xenon on Mars with Mars Science Laboratory". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 454: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.08.028. ISSN 0012-821X. Bibcode: 2016E&PSL.454....1C. http://oro.open.ac.uk/47798/1/conrad%2B%2B2016_accepted.pdf. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ↑ "Curiosity Sniffs Out History of Martian Atmosphere". http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4532.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 mars.nasa.gov. "NASA's MAVEN reveals most of Mars' atmosphere was lost to space". https://mars.nasa.gov/news/1976/nasas-maven-reveals-most-of-mars-atmosphere-was-lost-to-space.

- ↑ Catling, David C.; Zahnle, Kevin J. (May 2009). "The planetary air leak". Scientific American: 26. http://faculty.washington.edu/dcatling/Catling2009_SciAm.pdf. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Avice, G.; Bekaert, D.V.; Chennaoui Aoudjehane, H.; Marty, B. (9 February 2018). "Noble gases and nitrogen in Tissint reveal the composition of the Mars atmosphere". Geochemical Perspectives Letters 6: 11–16. doi:10.7185/geochemlet.1802.

- ↑ McElroy, Michael B.; Yung, Yuk Ling; Nier, Alfred O. (1 Oct 1976). "Isotopic Composition of Nitrogen: Implications for the Past History of Mars' Atmosphere". Science 194 (4260): 70–72. doi:10.1126/science.194.4260.70. PMID 17793081. Bibcode: 1976Sci...194...70M.

- ↑ Hunten, Donald M.; Pepin, Robert O.; Walker, James C.G. (1987-03-01). "Mass fractionation in hydrodynamic escape". Icarus 69 (3): 532–549. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90022-4. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 1987Icar...69..532H.

- ↑ Hans Keppler; Shcheka, Svyatoslav S. (October 2012). "The origin of the terrestrial noble-gas signature". Nature 490 (7421): 531–534. doi:10.1038/nature11506. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 23051754. Bibcode: 2012Natur.490..531S.

- ↑ Tian, Feng; Kasting, James F.; Solomon, Stanley C. (2009). "Thermal escape of carbon from the early Martian atmosphere". Geophysical Research Letters 36 (2): n/a. doi:10.1029/2008GL036513. ISSN 1944-8007. Bibcode: 2009GeoRL..36.2205T.

- ↑ Jakosky, B.M.; Slipski, M.; Benna, M.; Mahaffy, P.; Elrod, M.; Yelle, R.; Stone, S.; Alsaeed, N. (2017-03-31). "Mars' atmospheric history derived from upper-atmosphere measurements of 38Ar / 36Ar". Science 355 (6332): 1408–1410. doi:10.1126/science.aai7721. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28360326. Bibcode: 2017Sci...355.1408J.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Leblanc, F.; Martinez, A.; Chaufray, J. Y.; Modolo, R.; Hara, T.; Luhmann, J.; Lillis, R.; Curry, S. et al. (2018). "On Mars's Atmospheric Sputtering After MAVEN's First Martian Year of Measurements". Geophysical Research Letters 45 (10): 4685–4691. doi:10.1002/2018GL077199. ISSN 1944-8007. Bibcode: 2018GeoRL..45.4685L. https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-03737439/file/Geophysical%20Research%20Letters%20-%202018%20-%20Leblanc%20-%20On%20Mars%20s%20Atmospheric%20Sputtering%20After%20MAVEN%20s%20First%20Martian%20Year%20of.pdf.

- ↑ Vickery, A.M.; Melosh, H.J. (April 1989). "Impact erosion of the primordial atmosphere of Mars". Nature 338 (6215): 487–489. doi:10.1038/338487a0. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11536608. Bibcode: 1989Natur.338..487M.

- ↑ Owen, Tobias; Bar-Nun, Akiva (1995-08-01). "Comets, impacts, and atmospheres". Icarus 116 (2): 215–226. doi:10.1006/icar.1995.1122. ISSN 0019-1035. PMID 11539473. Bibcode: 1995Icar..116..215O.

- ↑ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2002). "Mars' upper atmosphere and ionosphere at low, medium, and high solar activities: Implications for evolution of water". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 107 (E12): 11‑1–11‑11. doi:10.1029/2001JE001809. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 2002JGRE..107.5128K.

- ↑ Sagan, Carl (September 1977). "Reducing greenhouses and the temperature history of Earth and Mars". Nature 269 (5625): 224–226. doi:10.1038/269224a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Bibcode: 1977Natur.269..224S.

- ↑ Kasting, James F.; Freedman, Richard; Robinson, Tyler D.; Zugger, Michael E.; Kopparapu, Ravi; Ramirez, Ramses M. (January 2014). "Warming early Mars with CO2 and H2". Nature Geoscience 7 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1038/ngeo2000. ISSN 1752-0908. Bibcode: 2014NatGe...7...59R.

- ↑ Batalha, Natasha; Domagal-Goldman, Shawn D.; Ramirez, Ramses; Kasting, James F. (2015-09-15). "Testing the early Mars H2–CO2 greenhouse hypothesis with a 1-D photochemical model". Icarus 258: 337–349. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.016. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2015Icar..258..337B.

- ↑ Johnson, Sarah Stewart; Mischna, Michael A.; Grove, Timothy L.; Zuber, Maria T. (2008-08-08). "Sulfur-induced greenhouse warming on early Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research 113 (E8): E08005. doi:10.1029/2007JE002962. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 2008JGRE..113.8005J.

- ↑ Schrag, Daniel P.; Zuber, Maria T.; Halevy, Itay (2007-12-21). "A sulfur dioxide climate feedback on early Mars". Science 318 (5858): 1903–1907. doi:10.1126/science.1147039. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18096802. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318.1903H.

- ↑ "Sulfur dioxide may have helped maintain a warm early Mars". https://phys.org/news/2007-12-sulfur-dioxide-early-mars.html.

- ↑ Anderson, Donald E. (1974). "Mariner 6, 7, and 9 Ultraviolet Spectrometer Experiment: Analysis of hydrogen Lyman alpha data". Journal of Geophysical Research 79 (10): 1513–1518. doi:10.1029/JA079i010p01513. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 1974JGR....79.1513A.

- ↑ Chaufray, J.Y.; Bertaux, J.L.; Leblanc, F.; Quémerais, E. (June 2008). "Observation of the hydrogen corona with SPICAM on Mars Express". Icarus 195 (2): 598–613. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2008.01.009. Bibcode: 2008Icar..195..598C.

- ↑ Hunten, Donald M. (November 1973). "The Escape of Light Gases from Planetary Atmospheres". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 30 (8): 1481–1494. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1973)030<1481:TEOLGF>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-4928. Bibcode: 1973JAtS...30.1481H.

- ↑ Zahnle, Kevin; Haberle, Robert M.; Catling, David C.; Kasting, James F. (2008). "Photochemical instability of the ancient Martian atmosphere". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 113 (E11): E11004. doi:10.1029/2008JE003160. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 2008JGRE..11311004Z.

- ↑ Bhattacharyya, D.; Clarke, J. T.; Chaufray, J. Y.; Mayyasi, M.; Bertaux, J. L.; Chaffin, M. S.; Schneider, N. M.; Villanueva, G. L. (2017). "Seasonal Changes in Hydrogen Escape From Mars Through Analysis of HST Observations of the Martian Exosphere Near Perihelion". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 122 (11): 11,756–11,764. doi:10.1002/2017JA024572. ISSN 2169-9402. Bibcode: 2017JGRA..12211756B. https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-01636632/file/2017JA024572.pdf. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Schofield, John T.; Shirley, James H.; Piqueux, Sylvain; McCleese, Daniel J.; Paul O. Hayne; Kass, David M.; Halekas, Jasper S.; Chaffin, Michael S. et al. (February 2018). "Hydrogen escape from Mars enhanced by deep convection in dust storms". Nature Astronomy 2 (2): 126–132. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0353-4. ISSN 2397-3366. Bibcode: 2018NatAs...2..126H.

- ↑ Shekhtman, Svetlana (2019-04-29). "How Global Dust Storms Affect Martian Water, Winds, and Climate". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2019/martian-dust-could-help-explain-planet-s-water-loss-plus-other-learnings-from-recent-global.

- ↑ Nagy, Andrew F.; Liemohn, Michael W.; Fox, J. L.; Kim, Jhoon (2001). "Hot carbon densities in the exosphere of Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 106 (A10): 21565–21568. doi:10.1029/2001JA000007. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 2001JGR...10621565N. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/physics/18. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Gröller, H.; Lichtenegger, H.; Lammer, H.; Shematovich, V. I. (2014-08-01). "Hot oxygen and carbon escape from the martian atmosphere". Planetary and Space Science. Planetary evolution and life 98: 93–105. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2014.01.007. ISSN 0032-0633. Bibcode: 2014P&SS...98...93G.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Fox, J. L. (1993). "The production and escape of nitrogen atoms on Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 98 (E2): 3297–3310. doi:10.1029/92JE02289. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 1993JGR....98.3297F. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1378&context=physics. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Mandt, Kathleen; Mousis, Olivier; Chassefière, Eric (July 2015). "Comparative planetology of the history of nitrogen isotopes in the atmospheres of Titan and Mars". Icarus 254: 259–261. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.03.025. PMID 31118538. Bibcode: 2015Icar..254..259M.

- ↑ Fox, J.L. (December 2007). "Comment on the papers "Production of hot nitrogen atoms in the martian thermosphere" by F. Bakalian and "Monte Carlo computations of the escape of atomic nitrogen from Mars" by F. Bakalian and R.E. Hartle". Icarus 192 (1): 296–301. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.05.022. Bibcode: 2007Icar..192..296F.

- ↑ Feldman, Paul D.; Steffl, Andrew J.; Parker, Joel Wm.; A'Hearn, Michael F.; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Alan Stern, S.; Weaver, Harold A.; Slater, David C. et al. (2011-08-01). "Rosetta-Alice observations of exospheric hydrogen and oxygen on Mars". Icarus 214 (2): 394–399. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.06.013. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2011Icar..214..394F.

- ↑ Lammer, H.; Lichtenegger, H.I.M.; Kolb, C.; Ribas, I.; Guinan, E.F.; Abart, R.; Bauer, S.J. (September 2003). "Loss of water from Mars". Icarus 165 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00170-2.

- ↑ Valeille, Arnaud; Bougher, Stephen W.; Tenishev, Valeriy; Combi, Michael R.; Nagy, Andrew F. (2010-03-01). "Water loss and evolution of the upper atmosphere and exosphere over martian history". Icarus. Solar Wind Interactions with Mars 206 (1): 28–39. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.04.036. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2010Icar..206...28V.

- ↑ Jones, Nancy; Steigerwald, Bill; Brown, Dwayne; Webster, Guy (14 October 2014). "NASA Mission Provides Its First Look at Martian Upper Atmosphere". NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2014-351.

- ↑ "Seasons on Mars". https://www.msss.com/http/ps/seasons/seasons.html.

- ↑ Soto, Alejandro; Mischna, Michael; Schneider, Tapio; Lee, Christopher; Richardson, Mark (2015-04-01). "Martian atmospheric collapse: Idealized GCM studies". Icarus 250: 553–569. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.028. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2015Icar..250..553S. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/53068/1/1-s2.0-S0019103514006575-main.pdf. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Hess, Seymour L.; Henry, Robert M.; Tillman, James E. (1979). "The seasonal variation of atmospheric pressure on Mars as affected by the south polar cap" (in en). Journal of Geophysical Research 84 (B6): 2923. doi:10.1029/JB084iB06p02923. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 1979JGR....84.2923H. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1029/JB084iB06p02923.

- ↑ Hess, S. L.; Ryan, J. A.; Tillman, J. E.; Henry, R. M.; Leovy, C. B. (March 1980). "The annual cycle of pressure on Mars measured by Viking Landers 1 and 2" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 7 (3): 197–200. doi:10.1029/GL007i003p00197. Bibcode: 1980GeoRL...7..197H. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1029/GL007i003p00197.

- ↑ Ordonez-Etxeberria, Iñaki; Hueso, Ricardo; Sánchez-Lavega, Agustín; Millour, Ehouarn; Forget, Francois (January 2019). "Meteorological pressure at Gale crater from a comparison of REMS/MSL data and MCD modelling: Effect of dust storms" (in en). Icarus 317: 591–609. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.09.003. Bibcode: 2019Icar..317..591O.

- ↑ Guzewich, Scott D.; Newman, C.E.; de la Torre Juárez, M.; Wilson, R.J.; Lemmon, M.; Smith, M.D.; Kahanpää, H.; Harri, A.-M. (April 2016). "Atmospheric tides in Gale Crater, Mars" (in en). Icarus 268: 37–49. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.12.028. Bibcode: 2016Icar..268...37G. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0019103515005850.

- ↑ Haberle, Robert M.; Juárez, Manuel de la Torre; Kahre, Melinda A.; Kass, David M.; Barnes, Jeffrey R.; Hollingsworth, Jeffery L.; Harri, Ari-Matti; Kahanpää, Henrik (June 2018). "Detection of Northern Hemisphere transient eddies at Gale Crater Mars" (in en). Icarus 307: 150–160. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.02.013. Bibcode: 2018Icar..307..150H. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0019103517304311.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Fanale, F. P.; Cannon, W. A. (April 1971). "Adsorption on the Martian Regolith" (in en). Nature 230 (5295): 502–504. doi:10.1038/230502a0. ISSN 0028-0836. Bibcode: 1971Natur.230..502F. https://www.nature.com/articles/230502a0.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Zent, Aaron P.; Quinn, Richard C. (1995). "Simultaneous adsorption of CO 2 and H 2 O under Mars-like conditions and application to the evolution of the Martian climate" (in en). Journal of Geophysical Research 100 (E3): 5341. doi:10.1029/94JE01899. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 1995JGR...100.5341Z. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1029/94JE01899.

- ↑ Moores, John E.; Gough, Raina V.; Martinez, German M.; Meslin, Pierre-Yves; Smith, Christina L.; Atreya, Sushil K.; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Newman, Claire E. et al. (May 2019). "Methane seasonal cycle at Gale Crater on Mars consistent with regolith adsorption and diffusion" (in en). Nature Geoscience 12 (5): 321–325. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0313-y. ISSN 1752-0894. Bibcode: 2019NatGe..12..321M. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-019-0313-y.

- ↑ Meslin, P.-Y.; Gough, R.; Lefèvre, F.; Forget, F. (February 2011). "Little variability of methane on Mars induced by adsorption in the regolith" (in en). Planetary and Space Science 59 (2–3): 247–258. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2010.09.022. Bibcode: 2011P&SS...59..247M. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0032063310002941.

- ↑ "Greenhouse effects ... also on other planets". European Space Agency. https://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Venus_Express/Greenhouse_effects_also_on_other_planets.

- ↑ Yung, Yuk L.; Kirschvink, Joseph L.; Pahlevan, Kaveh; Li, King-Fai (2009-06-16). "Atmospheric pressure as a natural climate regulator for a terrestrial planet with a biosphere". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (24): 9576–9579. doi:10.1073/pnas.0809436106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 19487662. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.9576L.

- ↑ McElroy, M.B.; Donahue, T.M. (1972-09-15). "Stability of the Martian atmosphere". Science 177 (4053): 986–988. doi:10.1126/science.177.4053.986. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17788809. Bibcode: 1972Sci...177..986M.

- ↑ Parkinson, T.D.; Hunten, D.M. (October 1972). "Spectroscopy and acronomy of O2 on Mars". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 29 (7): 1380–1390. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1972)029<1380:SAAOOO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-4928. Bibcode: 1972JAtS...29.1380P.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Stevens, M.H.; Siskind, D.E.; Evans, J.S.; Jain, S.K.; Schneider, N.M.; Deighan, J.; Stewart, A.I.F.; Crismani, M. et al. (2017-05-28). "Martian mesospheric cloud observations by IUVS on MAVEN: Thermal tides coupled to the upper atmosphere: IUVS Martian Mesospheric Clouds". Geophysical Research Letters 44 (10): 4709–4715. doi:10.1002/2017GL072717.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 González-Galindo, Francisco; Määttänen, Anni; Forget, François; Spiga, Aymeric (2011-11-01). "The martian mesosphere as revealed by CO2 cloud observations and general circulation modeling". Icarus 216 (1): 10–22. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.08.006. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2011Icar..216...10G.

- ↑ Stevens, M.H.; Evans, J.S.; Schneider, N.M.; Stewart, A.I.F.; Deighan, J.; Jain, S.K.; Crismani, M.; Stiepen, A. et al. (2015). "New observations of molecular nitrogen in the Martian upper atmosphere by IUVS on MAVEN". Geophysical Research Letters 42 (21): 9050–9056. doi:10.1002/2015GL065319. Bibcode: 2015GeoRL..42.9050S.

- ↑ Mandt, Kathleen; Mousis, Olivier; Chassefière, Eric (1 July 2015). "Comparative planetology of the history of nitrogen isotopes in the atmospheres of Titan and Mars". Icarus 254: 259–261. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.03.025. PMID 31118538. Bibcode: 2015Icar..254..259M.

- ↑ Webster, Guy (8 April 2013). "Remaining Martian atmosphere still dynamic" (Press release). NASA. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (8 April 2013). "Most of Mars' atmosphere is lost in space". http://www.space.com/20560-mars-atmosphere-lost-curiosity-rover.html.

- ↑ Hartogh, P.; Jarchow, C.; Lellouch, E.; de Val-Borro, M.; Rengel, M.; Moreno, R. et al. (2010). "Herschel / HIFI observations of Mars: First detection of O2 at sub-millimetre wavelengths and upper limits on HCL and H2O2". Astronomy and Astrophysics 521: L49. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015160. Bibcode: 2010A&A...521L..49H. https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15160-10/aa15160-10.html. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ↑ "Flying Observatory Detects Atomic Oxygen in Martian Atmosphere – NASA". 6 May 2016. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/ames/sofia/flying-observatory-detects-atomic-oxygen-in-martian-atmosphere.

- ↑ "Nasa probes oxygen mystery on Mars". 14 November 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-50419917.

- ↑ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2006-11-01). "Photochemistry of the martian atmosphere: Seasonal, latitudinal, and diurnal variations". Icarus 185 (1): 153–170. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.003. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2006Icar..185..153K.

- ↑ Perrier, S.; Bertaux, J.L.; Lefèvre, F.; Lebonnois, S.; Korablev, O.; Fedorova, A.; Montmessin, F. (2006). "Global distribution of total ozone on Mars from SPICAM/MEX UV measurements". Journal of Geophysical Research. Planets 111 (E9): E09S06. doi:10.1029/2006JE002681. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 2006JGRE..111.9S06P.

- ↑ Perrier, Séverine; Montmessin, Franck; Lebonnois, Sébastien; Forget, François; Fast, Kelly; Encrenaz, Thérèse et al. (August 2008). "Heterogeneous chemistry in the atmosphere of Mars". Nature 454 (7207): 971–975. doi:10.1038/nature07116. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 18719584. Bibcode: 2008Natur.454..971L.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Franck Lefèvre; Montmessin, Franck (November 2013). "Transport-driven formation of a polar ozone layer on Mars". Nature Geoscience 6 (11): 930–933. doi:10.1038/ngeo1957. ISSN 1752-0908. Bibcode: 2013NatGe...6..930M.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "A seasonal ozone layer over the Martian south pole". European Space Agency. http://sci.esa.int/mars-express/52881-a-seasonal-ozone-layer-over-the-martian-south-pole/.

- ↑ Lebonnois, Sébastien; Quémerais, Eric; Montmessin, Franck; Lefèvre, Franck; Perrier, Séverine; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Forget, François (2006). "Vertical distribution of ozone on Mars as measured by SPICAM/Mars Express using stellar occultations". Journal of Geophysical Research. Planets 111 (E9): E09S05. doi:10.1029/2005JE002643. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 2006JGRE..111.9S05L. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00109865/file/8fb300f315ff537a95f0f59c8d42b449f415.pdf. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Titov, D.V. (2002-01-01). "Water vapour in the atmosphere of Mars". Advances in Space Research 29 (2): 183–191. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(01)00568-3. ISSN 0273-1177. Bibcode: 2002AdSpR..29..183T.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Whiteway, J.A.; Komguem, L.; Dickinson, C.; Cook, C.; Illnicki, M.; Seabrook, J.; Popovici, V.; Duck, T. J. et al. (2009-07-03). "Mars Water-Ice Clouds and Precipitation". Science 325 (5936): 68–70. doi:10.1126/science.1172344. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19574386. Bibcode: 2009Sci...325...68W.

- ↑ Jakosky, Bruce M.; Farmer, Crofton B. (1982). "The seasonal and global behavior of water vapor in the Mars atmosphere: Complete global results of the Viking Atmospheric Water Detector Experiment". Journal of Geophysical Research. Solid Earth 87 (B4): 2999–3019. doi:10.1029/JB087iB04p02999. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 1982JGR....87.2999J.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Trokhimovskiy, Alexander; Fedorova, Anna; Korablev, Oleg; Montmessin, Franck; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; Rodin, Alexander; Smith, Michael D. (2015-05-01). "Mars' water vapor mapping by the SPICAM IR spectrometer: Five martian years of observations". Icarus. Dynamic Mars 251: 50–64. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2014.10.007. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2015Icar..251...50T.

- ↑ "Scientists 'map' water vapor in Martian atmosphere". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/12/141222111603.htm.

- ↑ mars.nasa.gov. "Mars Exploration Rover". NASA. https://mars.nasa.gov/mer/.

- ↑ Ice Clouds in Martian Arctic. www.nasa.gov (accelerated movie). NASA. Retrieved 2019-06-08.

- ↑ Montmessin, Franck; Forget, François; Millour, Ehouarn; Navarro, Thomas; Madeleine, Jean-Baptiste; Hinson, David P.; Spiga, Aymeric (September 2017). "Snow precipitation on Mars driven by cloud-induced night-time convection". Nature Geoscience 10 (9): 652–657. doi:10.1038/ngeo3008. ISSN 1752-0908. Bibcode: 2017NatGe..10..652S.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 esa. "The methane mystery". https://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/Exploration/ExoMars/The_methane_mystery.

- ↑ Potter, Sean (2018-06-07). "NASA Finds Ancient Organic Material, Mysterious Methane on Mars". http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-finds-ancient-organic-material-mysterious-methane-on-mars.

- ↑ Witze, Alexandra (2018-10-25). "Mars scientists edge closer to solving methane mystery". Nature 563 (7729): 18–19. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-07177-4. PMID 30377322. Bibcode: 2018Natur.563...18W.

- ↑ Formisano, Vittorio; Atreya, Sushil; Encrenaz, Thérèse; Ignatiev, Nikolai; Giuranna, Marco (2004-12-03). "Detection of Methane in the Atmosphere of Mars". Science 306 (5702): 1758–1761. doi:10.1126/science.1101732. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15514118. Bibcode: 2004Sci...306.1758F.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A.; Maillard, Jean Pierre; Owen, Tobias C. (December 2004). "Detection of methane in the martian atmosphere: evidence for life?". Icarus 172 (2): 537–547. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.07.004. Bibcode: 2004Icar..172..537K.

- ↑ Geminale, A.; Formisano, V.; Giuranna, M. (July 2008). "Methane in Martian atmosphere: Average spatial, diurnal, and seasonal behaviour". Planetary and Space Science 56 (9): 1194–1203. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2008.03.004. Bibcode: 2008P&SS...56.1194G.

- ↑ Mumma, M.J.; Villanueva, G.L.; Novak, R.E.; Hewagama, T.; Bonev, B.P.; DiSanti, M.A.; Mandell, A.M.; Smith, M.D. (2009-02-20). "Strong Release of Methane on Mars in Northern Summer 2003". Science 323 (5917): 1041–1045. doi:10.1126/science.1165243. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19150811. Bibcode: 2009Sci...323.1041M.

- ↑ Fonti, S.; Marzo, G.A. (March 2010). "Mapping the methane on Mars". Astronomy and Astrophysics 512: A51. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913178. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2010A&A...512A..51F.

- ↑ Geminale, A.; Formisano, V.; Sindoni, G. (2011-02-01). "Mapping methane in Martian atmosphere with PFS-MEX data". Planetary and Space Science. Methane on Mars: Current Observations, Interpretation and Future Plans 59 (2): 137–148. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2010.07.011. ISSN 0032-0633. Bibcode: 2011P&SS...59..137G.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Webster, C. R.; Mahaffy, P. R.; Atreya, S. K.; Flesch, G. J.; Mischna, M. A.; Meslin, P.-Y.; Farley, K. A.; Conrad, P. G. et al. (2015-01-23). "Mars methane detection and variability at Gale crater". Science 347 (6220): 415–417. doi:10.1126/science.1261713. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25515120. Bibcode: 2015Sci...347..415W. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/52526/7/Webster.SM.pdf. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Vasavada, Ashwin R.; Zurek, Richard W.; Sander, Stanley P.; Crisp, Joy; Lemmon, Mark; Hassler, Donald M.; Genzer, Maria; Harri, Ari-Matti et al. (2018-06-08). "Background levels of methane in Mars' atmosphere show strong seasonal variations". Science 360 (6393): 1093–1096. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0131. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29880682. Bibcode: 2018Sci...360.1093W.

- ↑ Amoroso, Marilena; Merritt, Donald; Parra, Julia Marín-Yaseli de la; Cardesín-Moinelo, Alejandro; Aoki, Shohei; Wolkenberg, Paulina; Alessandro Aronica; Formisano, Vittorio et al. (May 2019). "Independent confirmation of a methane spike on Mars and a source region east of Gale Crater". Nature Geoscience 12 (5): 326–332. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0331-9. ISSN 1752-0908. Bibcode: 2019NatGe..12..326G.

- ↑ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A. (2005-11-15). "A sensitive search for SO2 in the martian atmosphere: Implications for seepage and origin of methane". Icarus. Jovian Magnetospheric Environment Science 178 (2): 487–492. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.05.006. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2005Icar..178..487K.

- ↑ Hecht, Jeff. "Volcanoes ruled out for Martian methane". https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn8256-volcanoes-ruled-out-for-martian-methane/.

- ↑ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A (2012). "Search for methane and upper limits to ethane and SO2 on Mars". Icarus 217 (1): 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.019. Bibcode: 2012Icar..217..144K.

- ↑ Encrenaz, T.; Greathouse, T. K.; Richter, M. J.; Lacy, J. H.; Fouchet, T.; Bézard, B.; Lefèvre, F.; Forget, F. et al. (2011). "A stringent upper limit to SO2 in the Martian atmosphere". Astronomy and Astrophysics 530: 37. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116820. Bibcode: 2011A&A...530A..37E.

- ↑ McAdam, A. C.; Franz, H.; Archer, P. D.; Freissinet, C.; Sutter, B.; Glavin, D. P.; Eigenbrode, J. L.; Bower, H.; Stern, J.; Mahaffy, P. R.; Morris, R. V.; Ming, D. W.; Rampe, E.; Brunner, A. E.; Steele, A.; Navarro-González, R.; Bish, D. L.; Blake, D.; Wray, J.; Grotzinger, J.; MSL Science Team (2013). "Insights into the Sulfur Mineralogy of Martian Soil at Rocknest, Gale Crater, Enabled by Evolved Gas Analyses". 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, held 18–22 March 2013 in The Woodlands, Texas. LPI Contribution No. 1719, p. 1751

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Owen, T.; Biemann, K.; Rushneck, D. R.; Biller, J. E.; Howarth, D. W.; Lafleur, A. L. (1976-12-17). "The Atmosphere of Mars: Detection of Krypton and Xenon". Science 194 (4271): 1293–1295. doi:10.1126/science.194.4271.1293. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17797086. Bibcode: 1976Sci...194.1293O.

- ↑ Owen, Tobias; Biemann, K.; Rushneck, D. R.; Biller, J. E.; Howarth, D. W.; Lafleur, A. L. (1977). "The composition of the atmosphere at the surface of Mars". Journal of Geophysical Research 82 (28): 4635–4639. doi:10.1029/JS082i028p04635. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 1977JGR....82.4635O.

- ↑ Krasnopolsky, Vladimir A.; Gladstone, G. Randall (2005-08-01). "Helium on Mars and Venus: EUVE observations and modeling". Icarus 176 (2): 395–407. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.02.005. ISSN 0019-1035. Bibcode: 2005Icar..176..395K.

- ↑ "Curiosity finds evidence of Mars crust contributing to atmosphere". NASA. http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6631.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Krasnopolsky, V. A. (2001-11-30). "Detection of Molecular Hydrogen in the Atmosphere of Mars". Science 294 (5548): 1914–1917. doi:10.1126/science.1065569. PMID 11729314. Bibcode: 2001Sci...294.1914K.

- ↑ Smith, Michael D. (May 2008). "Spacecraft Observations of the Martian Atmosphere". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 36 (1): 191–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124334. ISSN 0084-6597. Bibcode: 2008AREPS..36..191S.

- ↑ Withers, Paul; Catling, D. C. (December 2010). "Observations of atmospheric tides on Mars at the season and latitude of the Phoenix atmospheric entry". Geophysical Research Letters 37 (24): n/a. doi:10.1029/2010GL045382. Bibcode: 2010GeoRL..3724204W.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 Leovy, Conway (July 2001). "Weather and climate on Mars". Nature 412 (6843): 245–249. doi:10.1038/35084192. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11449286. Bibcode: 2001Natur.412..245L.

- ↑ Petrosyan, A.; Galperin, B.; Larsen, S. E.; Lewis, S. R.; Määttänen, A.; Read, P. L.; Renno, N.; Rogberg, L. P. H. T. et al. (2011-09-17). "The Martian Atmospheric Boundary Layer". Reviews of Geophysics 49 (3): RG3005. doi:10.1029/2010RG000351. ISSN 8755-1209. Bibcode: 2011RvGeo..49.3005P.

- ↑ Catling, David C. (13 April 2017). Atmospheric evolution on inhabited and lifeless worlds. Kasting, James F.. Cambridge. ISBN 9780521844123. OCLC 956434982. Bibcode: 2017aeil.book.....C.

- ↑ Robinson, T. D.; Catling, D. C. (January 2014). "Common 0.1 bar tropopause in thick atmospheres set by pressure-dependent infrared transparency". Nature Geoscience 7 (1): 12–15. doi:10.1038/ngeo2020. ISSN 1752-0894. Bibcode: 2014NatGe...7...12R.

- ↑ Forget, François; Montmessin, Franck; Bertaux, Jean-Loup; González-Galindo, Francisco; Lebonnois, Sébastien; Quémerais, Eric; Reberac, Aurélie; Dimarellis, Emmanuel et al. (2009-01-28). "Density and temperatures of the upper Martian atmosphere measured by stellar occultations with Mars Express SPICAM". Journal of Geophysical Research 114 (E1): E01004. doi:10.1029/2008JE003086. ISSN 0148-0227. Bibcode: 2009JGRE..114.1004F. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00357038/file/Forget_et_al-2009-Journal_of_Geophysical_Research__Solid_Earth_%281978-2012%29.pdf. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- ↑ Bougher, S. W.; Pawlowski, D.; Bell, J. M.; Nelli, S.; McDunn, T.; Murphy, J. R.; Chizek, M.; Ridley, A. (February 2015). "Mars Global Ionosphere-Thermosphere Model: Solar cycle, seasonal, and diurnal variations of the Mars upper atmosphere: BOUGHER ET AL.". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 120 (2): 311–342. doi:10.1002/2014JE004715.

- ↑ Bougher, Stephen W.; Roeten, Kali J.; Olsen, Kirk; Mahaffy, Paul R.; Benna, Mehdi; Elrod, Meredith; Jain, Sonal K.; Schneider, Nicholas M. et al. (2017). "The structure and variability of Mars dayside thermosphere from MAVEN NGIMS and IUVS measurements: Seasonal and solar activity trends in scale heights and temperatures". Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 122 (1): 1296–1313. doi:10.1002/2016JA023454. ISSN 2169-9402. Bibcode: 2017JGRA..122.1296B.

- ↑ Zell, Holly (2015-05-29). "MAVEN Captures Aurora on Mars". http://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/goddard/maven-captures-aurora-on-mars.