Delphinus

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 13 min

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Del |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Delphini |

| Pronunciation | /dɛlˈfaɪnəs/ Delfínus, genitive /dɛlˈfaɪnaɪ/ |

| Symbolism | dolphin |

| Right ascension | 20h 14m 14.1594s to 21h 08m 59.6073s[1] |

| Declination | +2.4021468° to +20.9399471°[1] |

| Quadrant | NQ4 |

| Area | 189 sq. deg. (69th) |

| Main stars | 5 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 19 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 0 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 3 |

| Brightest star | Rotanev (β Del) (3.63m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | None |

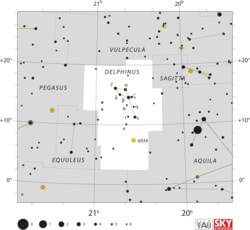

| Bordering constellations | Vulpecula Sagitta Aquila Aquarius Equuleus Pegasus |

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −69°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of September. | |

Delphinus is a small constellation in the Northern Celestial Hemisphere, close to the celestial equator. Its name is the Latin version for the Greek word for dolphin (δελφίς). It is one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and remains one of the 88 modern constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union. It is one of the smaller constellations, ranked 69th in size. Delphinus' five brightest stars form a distinctive asterism symbolizing a dolphin with four stars representing the body and one the tail. It is bordered (clockwise from north) by Vulpecula, Sagitta, Aquila, Aquarius, Equuleus and Pegasus.

Delphinus is a faint constellation with only two stars brighter than an apparent magnitude of 4, Beta Delphini (Rotanev) at magnitude 3.6 and Alpha Delphini (Sualocin) at magnitude 3.8.

Mythology

Delphinus is associated with two stories from Greek mythology.

According to myth, the first Greek god Poseidon wanted to marry Amphitrite, a beautiful nereid. However, wanting to protect her virginity, she fled to the Atlas Mountains. Her suitor then sent out several searchers, among them a certain Delphinus. Delphinus accidentally stumbled upon her and persuaded Amphitrite to accept Poseidon's wooing. Out of gratitude, the god placed the image of a dolphin among the stars.[2]

The second story tells of the Greek poet Arion of Lesbos (7th century BC), who a dolphin saved.[3] He was a court musician at the palace of Periander, ruler of Corinth. Arion had amassed a fortune during his travels to Sicily and Italy. On his way home from Tarentum, his wealth caused the crew of his ship to conspire against him. Threatened with death, Arion asked to be granted a last wish, which the crew granted: he wanted to sing a dirge.[4] This he did, and while doing so, flung himself into the sea. There, he was rescued by a dolphin which had been charmed by Arion's music. The dolphin carried Arion to the coast of Greece and left.[5]

In non-Western astronomy

In Chinese astronomy, the stars of Delphinus are located within the Black Tortoise of the North (北方玄武, Běi Fāng Xuán Wǔ).[6]

In Polynesia, two cultures recognized Delphinus as a constellation. In Pukapuka, it was called Te Toloa and in the Tuamotus, it was called Te Uru-o-tiki.[7]

In Hindu astrology, the Delphinus corresponds to the Nakshatra, or lunar mansion, of Dhanishta.

Characteristics

Delphinus is bordered by Vulpecula to the north, Sagitta to the northwest, Aquila to the west and southwest, Aquarius to the southeast, Equuleus to the east and Pegasus to the east.[1] Covering 188.5 square degrees, corresponding to 0.457% of the sky, it ranks 69th of the 88 constellations in size.[8] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the IAU in 1922, is "Del".[9] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 14 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 20h 14m 14.1594s and 21h 08m 59.6073s, while the declination coordinates are between +2.4021468° and +20.9399471°.[1] The whole constellation is visible to observers north of latitude 69°S.[8][lower-alpha 1]

Features

Stars

Delphinus has two stars above fourth (apparent) magnitude; its brightest star is of magnitude 3.6. The main asterism in Delphinus is Job's Coffin,[citation needed] nearly a 45°-apex lozenge or diamond of the four brightest stars: Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta Delphini. Delphinus is in a rich Milky Way star field. Alpha and Beta Delphini have 19th-century names Sualocin and Rotanev, read backwards: Nicolaus Venator, the Latinized name of a Palermo Observatory director, Niccolò Cacciatore (d. 1841).[3]

Alpha Delphini is a blue-white hued main sequence star of magnitude 3.8,[10] 241 light-years from Earth. It is a spectroscopic binary.[11] It is officially named Sualocin.[12][13] The star has an absolute magnitude of -0.4.[14]

Beta Delphini is officially called Rotanev.[12] It was found to be a binary star in 1873.[15] The gap between its close binary stars is visible from large amateur telescopes. To the unaided eye, it appears to be a white star of magnitude 3.6.[16][15] It has a period of 27 years and is 97 light-years from Earth.

Gamma Delphini is a celebrated binary star among amateur astronomers. The primary is orange-gold of magnitude 4.3; the secondary is a light yellow star of magnitude 5.1. The pair forms a true binary with an estimated orbital period of over 3,000 years. 125 light-years away, the two components are visible in a small amateur telescope.[3] The secondary, also described as green, is 10 arcseconds from the primary. Struve 2725, called the "Ghost Double", is a pair that appears similar but dimmer. Its components of magnitudes 7.6 and 8.4 are separated by 6 arcseconds and are 15 arcminutes from Gamma Delphini itself.[5] An unconfirmed exoplanet with a minimum mass of 0.7 Jupiter masses may orbit one of the stars.[17][18]

Delta Delphini is a type A-type star[19] of magnitude 4.43.[20] It is a spectroscopic binary, and both stars are Delta Scuti variables.[21]

Epsilon Delphini, Deneb Dulfim (lit. "tail [of the] Dolphin"), or Aldulfin, is a star of stellar class B6 III.[22] Its magnitude is variable at around 4.03.[23][24]

Zeta Delphini, an A3Va[25] main-sequence star of magnitude 4.6, was in 2014 discovered to have a brown dwarf orbiting around it. Zeta Delphini B has a mass of 50±15 MJ.[25]

File:Aquila.fade-in.animation.webm Rho Aquilae at magnitude 4.94[26] is at about 150 light-years away.[26] Due to its proper motion, it has been in the (round-figure parameter) bounds of the constellation since 1992.[27] It is an A-type main sequence star with a lower metallicity than the Sun.[28]

HR Delphini was a nova that brightened to magnitude 3.5 in December 1967.[29] It took an unusually long time for the nova to reach peak brightness which indicate that it barely satisfied the conditions for a thermonuclear runaway.[30] Another nova by the name V339 Delphini was detected in 2013; it peaked at magnitude 4.3 and was the first nova observed to produce lithium.[31][32][33][34]

Musica, also known by its Flamsteed designation 18 Delphini, is one of the five stars with known planets located in Delphinus. It has a spectral type of G6 III.[35] Arion, the planet, is a very dense and massive planet with a mass at least 10.3 times greater than Jupiter.[36] Arion was part of the first NameExoWorlds contest where the public got the opportunity to suggest names for exoplanets and their host stars.[37]

Exoplanets

In 2024 the planet TOI-6883 b was discovered in the constellation Delphinus.[38] It has a 16.249 day orbital period around its host star,[39] a radius 1.08 times Jupiter's,[40] and a mass 4.34 times Jupiter's.[39] It was discovered from a single transit[40] in TESS data and it was confirmed by a network of citizen scientists.[39]

In 2024, the planet TOI-6883 c was discovered in the constellation Delphinus.[41] It has an orbital period of 7.8458 days, a radius of 0.7 times Jupiter's, and a third of Jupiter's mass. The Neptunian-size planet was discovered from an abnormality in data retrieved from TOI-6883 c.[42]

Deep-sky objects

Its rich Milky Way star field means many modestly deep-sky objects. NGC 6891 is a planetary nebula of magnitude 10.5; another is NGC 6905 or the Blue Flash Nebula. The Blue Flash Nebula shows broad emission lines. The central star in NGC 6905 has a spectral type of WO2, meaning it is rich in oxygen.[43]

NGC 6934 is a globular cluster of magnitude 9.75. It is about 52,000 light-years away from the Solar System.[44] It is in the Shapley-Sawyer Concentration Class VIII[45] and is thought to share a common origin with another globular cluster in Boötes.[46] It has an intermediate metallicity for a globular cluster,[47] but as of 2018 it has been poorly studied.[48] At a distance of about 137,000 light-years,[46] the globular cluster NGC 7006 is at the outer reaches of the galaxy. It is also fairly dim at magnitude 11.5 and is in Class I.[45]

See also

- Delphinus (Chinese astronomy)

Notes

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Delphinus, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations (International Astronomical Union). https://www.iau.org/public/themes/constellations/#del. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ Pseudo-Hyginus. "HYGINUS, ASTRONOMICA 2.1-17". http://www.theoi.com/Text/HyginusAstronomica.html#17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories I.23-24;

also Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae XVI.19; Plutarch, Conv. sept. sap. 160–62; Shakespeare, Twelfth Night (Act I, Sc 2, line 16) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schaaf, Fred (September 2012). "The Celestial Dolphin". Sky and Telescope 124 (3): 47. Bibcode: 2012S&T...124c..47S.

- ↑ Script error: The function "in_lang" does not exist. AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 7 月 4 日

- ↑ Makemson 1941, p. 283.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. Self-published. http://www.ianridpath.com/constellations1.html.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy 30: 469. Bibcode: 1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ Oja, T. (1991). "UBV photometry of stars whose positions are accurately known. VI". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 89: 415. Bibcode: 1991A&AS...89..415O.

- ↑ Malkov, O. Yu.; Tamazian, V. S.; Docobo, J. A.; Chulkov, D. A. (2012). "Dynamical masses of a selected sample of orbital binaries". Astronomy & Astrophysics 546: A69. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219774. Bibcode: 2012A&A...546A..69M.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern Star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ↑ "Naming Stars". IAU.org. https://www.iau.org/public/themes/naming_stars/. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ Jaschek, C.; Gomez, A. E. (1998). "The absolute magnitude of the early type MK standards from HIPPARCOS parallaxes". Astronomy and Astrophysics 330: 619. Bibcode: 1998A&A...330..619J.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Burnham, Robert (1978), Burnham's celestial handbook: an observer's guide to the universe beyond the Solar System, Dover Books on Astronomy, 2 (2nd ed.), Courier Dover Publications, p. 820, ISBN 0-486-23568-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=wB9uZ9lH5bgC&pg=PA820

- ↑ Davidson, James W. Jr. et al. (November 2009), "A Photometric Analysis of Seventeen Binary Stars Using Speckle Imaging", The Astronomical Journal 138 (5): 1354–1364, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/5/1354, Bibcode: 2009AJ....138.1354D

- ↑ Irwin, A. W. et al. (1999), Hearnshaw, J. B.; Scarfe, C. D., eds., "A Program for the Analysis of Long-Period Binaries: The Case of γ Delphini", Precise Stellar Radial Velocities. IAU Colloquium 170, ASP Conference Series #185 185: p. 297, ISBN 1-58381-011-0, Bibcode: 1999ASPC..185..297I

- ↑ Wittemeyer et al. (2006). "Detection Limits from the McDonald Observatory Planet Search Program". The Astronomical Journal 132 (1): 177–188. doi:10.1086/504942. Bibcode: 2006AJ....132..177W.

- ↑ Gray, R. O.; Napier, M. G.; Winkler, L. I. (April 2001), "The Physical Basis of Luminosity Classification in the Late A-, F-, and Early G-Type Stars. I. Precise Spectral Types for 372 Stars", The Astronomical Journal 121 (4): 2148–2158, doi:10.1086/319956, Bibcode: 2001AJ....121.2148G.

- ↑ Chang, S.-W. et al. (2013), "Statistical Properties of Galactic δ Scuti Stars: Revisited", The Astronomical Journal 145 (5): 132, doi:10.1088/0004-6256/145/5/132, Bibcode: 2013AJ....145..132C.

- ↑ Liakos, Alexios; Niarchos, Panagiotis (February 2017), "Catalogue and properties of δ Scuti stars in binaries", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 465 (1): 1181–1200, doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2756, Bibcode: 2017MNRAS.465.1181L.

- ↑ Lesh, Janet Rountree (December 1968), "The Kinematics of the Gould Belt: an Expanding Group?", Astrophysical Journal Supplement 17: 371, doi:10.1086/190179, Bibcode: 1968ApJS...17..371L.

- ↑ Samus, N. N. et al. (January 2017), "General Catalogue of Variable Stars", Astronomy Reports, GCVS 5.1 61 (1): 80–88, doi:10.1134/S1063772917010085, Bibcode: 2017ARep...61...80S.

- ↑ Crawford, D. L. et al. (1971), "Four-color, H-beta, and UBV photometry for bright B-type stars in the northern hemisphere", The Astronomical Journal 76: 1058, doi:10.1086/111220, Bibcode: 1971AJ.....76.1058C.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 De Rosa, R. J.; Patience, J.; Ward-Duong, K.; Vigan, A.; Marois, C.; Song, I.; Macintosh, B.; Graham, J. R. et al. (December 2014). "The VAST Survey - IV. A wide brown dwarf companion to the A3V star ζ Delphini" (in en). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 445 (4): 3694. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu2018. ISSN 0035-8711. Bibcode: 2014MNRAS.445.3694D.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Wielen, R. et al. (1999), "Sixth Catalogue of Fundamental Stars (FK6). Part I. Basic fundamental stars with direct solutions", Veroeffentlichungen des Astronomischen Rechen-Instituts Heidelberg (Astronomisches Rechen-Institut Heidelberg) 35 (35): 1, Bibcode: 1999VeARI..35....1W.

- ↑ Patrick Moore (29 June 2013). The Observer's Year: 366 Nights of the Universe. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-4471-3613-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=p87TBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA132.

- ↑ Anders, F.; Khalatyan, A.; Chiappini, C.; Queiroz, A. B.; Santiago, B. X.; Jordi, C.; Girardi, L.; Brown, A. G. A. et al. (1 August 2019), "Photo-astrometric distances, extinctions, and astrophysical parameters for Gaia DR2 stars brighter than G = 18", Astronomy and Astrophysics 628: A94, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935765, ISSN 0004-6361, Bibcode: 2019A&A...628A..94A.

- ↑ Isles, J. E. (1974). "HR Delphini (Nova 1967) in 1967 - 71". Journal of the British Astronomical Association 85: 54–58. Bibcode: 1974JBAA...85...54I.

- ↑ Friedjung, M (17 March 1992). "The unusual nature of nova HR Delphini 1967". Astronomy & Astrophysics 262 (262): 487. Bibcode: 1992A&A...262..487F. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1992A%26A...262..487F/abstract. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ Tajitsu, Akito; Sadakane, Kozo; Naito, Hiroyuki; Arai, Akira; Aoki, Wako (18 February 2015). "Explosive lithium production in the classical nova V339 Del (Nova Delphini 2013)". Nature 518 (7539): 381–384. doi:10.1038/nature14161. PMID 25693569. Bibcode: 2015Natur.518..381T.

- ↑ King, Bob (August 14, 2013). "Bright New Nova In Delphinus — You can See it Tonight With Binoculars". Universe Today (initial designation PNV J20233073+2046041). http://www.universetoday.com/104103/bright-new-nova-in-delphinus-you-can-see-it-tonight-with-binoculars.

- ↑ Guido, Ernesto; Ruocco, Nello; Howes, Nick (August 15, 2013). "Possible Bright Nova in Delphinus". Associazione Friulana di Astronomia e Meteorologia. http://remanzacco.blogspot.it/2013/08/possible-bright-nova-in-delphinus.html.

- ↑ Masi, Gianluca (August 15, 2013). "Nova Delphini 2013 (formerly PNV J20233073+2046041): images, spectra and maps". Gianluca Masi - Virtual Telescope Project. http://www.virtualtelescope.eu/2013/08/15/possible-nova-pnv-j202330732046041-in-delphinus/.

- ↑ Opolski, A. (1957). "The spectrophotometric parallaxes of 42 visual binaries". Arkiv för Astronomi 2: 55. Bibcode: 1957ArA.....2...55O.

- ↑ Sato, Bun’ei; Izumiura, Hideyuki; Toyota, Eri; Kambe, Eiji; Ikoma, Masahiro; Omiya, Masashi; Masuda, Seiji; Takeda, Yoichi et al. (25 June 2008). "Planetary Companions around Three Intermediate-Mass G and K Giants: 18 Delphini, ξ Aquilae, and HD 81688" (in en). Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 60 (3): 539–550. doi:10.1093/pasj/60.3.539. ISSN 0004-6264. Bibcode: 2008PASJ...60..539S. https://academic.oup.com/pasj/article/60/3/539/1508408.

- ↑ "International Astronomical Union | IAU". https://www.iau.org/news/pressreleases/detail/iau1514/.

- ↑ Martin, Pierre-Yves (2024). "Planet TOI-6883 b" (in en). https://exoplanet.eu/catalog/toi_6883_b--8968/.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Sgro, Lauren A.; Dalba, Paul A.; Esposito, Thomas M.; Marchis, Franck; Dragomir, Diana; Villanueva Jr., Steven; Fulton, Benjamin; Billiani, Mario et al. (2024-05-23). "Confirmation and Characterization of the Eccentric, Warm Jupiter TIC 393818343 b with a Network of Citizen Scientists". The Astronomical Journal 168 (1): 26. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ad5096. Bibcode: 2024AJ....168...26S.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Conzo, G.; Moriconi, M. (2024-02-26). "TOI-6883.01: A Single-transit Planet Candidate Detected from TESS". Research Notes of the AAS 8 (2): 53. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ad2c85. ISSN 2515-5172. Bibcode: 2024RNAAS...8...53C.

- ↑ Martin, Pierre-Yves (2024). "Planet TOI-6883 c" (in en). https://exoplanet.eu/catalog/toi_6883_c--10778/.

- ↑ Conzo, G.; Leiner, N.; Lynch, K.; Moriconi, M.; Ruocco, N.; Scarmato, T. (2024-10-09). "TIC 393818343 c: Discovery and characterization of a Neptune-like planet in the Delphinus constellation". arXiv:2410.07425 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ Gómez-González, V M A.; Rubio, G.; Toalá, J. A.; Guerrero, M. A.; Sabin, L.; Todt, H.; Gómez-Llanos, V.; Ramos-Larios, G. et al. (2022). "Planetary nebulae with Wolf–Rayet-type central stars – III. A detailed view of NGC 6905 and its central star". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 509: 974–989. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab3042.

- ↑ Dinescu, Dana I. et al. (October 2001). "Orbits of Globular Clusters in the Outer Galaxy: NGC 7006". The Astronomical Journal 122 (4): 1916–1927. doi:10.1086/323094. Bibcode: 2001AJ....122.1916D.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Shapley, Harlow; Sawyer, Helen B. (August 1927), "A Classification of Globular Clusters", Harvard College Observatory Bulletin 849 (849): 11–14, Bibcode: 1927BHarO.849...11S.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Hessels, J. W. T. et al. (November 2007), "A 1.4 GHz Arecibo Survey for Pulsars in Globular Clusters", The Astrophysical Journal 670 (1): 363–378, doi:10.1086/521780, Bibcode: 2007ApJ...670..363H.

- ↑ Kaluzny, J. et al. (March 2001). "Image-Subtraction Photometry of Variable Stars in the Field of the Globular Cluster NGC 6934". The Astronomical Journal 121 (3): 1533–1550. doi:10.1086/319411. Bibcode: 2001AJ....121.1533K.

- ↑ Marino, A. F. et al. (June 2018). "Metallicity Variations in the Type II Globular Cluster NGC 6934". The Astrophysical Journal 859 (2): 20. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aabdea. 81. Bibcode: 2018ApJ...859...81M.

<ref> tag with name "Kirkpatrick2024" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.References

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: An Account of Polynesian Astronomy. Yale University Press. Bibcode: 1941msra.book.....M.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017). Stars and planets guide. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-823927-5. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-691-17788-5.

- University of Wisconsin, "Delphinus"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Delphinus. |

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Delphinus

- The clickable Delphinus

- Star Tales – Delphinus

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of Delphinus)

Coordinates: ![]() 20h 42m 00s, +13° 48′ 00″

20h 42m 00s, +13° 48′ 00″

|

KSF

KSF