Kaal

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

Kāla (Sanskrit: काल, translit. kālá, [kaːlɐ]) is a word used in Sanskrit to mean "time".[1] It is also the name of a deity, in which sense it is not always distinguishable from kāla, meaning "black". It is often used as one of the various names or forms of Yama.

Etymology

Monier-Williams's widely used Sanskrit-English dictionary[2] lists two distinct words with the form kāla.

- kāla 1 means "black, of a dark colour, dark-blue ..." and has a feminine form ending in ī – kālī – as mentioned in Pāṇini 4–1, 42.

- kālá 2 means "a fixed or right point of time, a space of time, time ... destiny, fate ... death" and has a feminine form (found at the end of compounds) ending in ā, as mentioned in the ṛgveda Prātiśākhya. As a traditional Hindu unit of time, one kālá corresponds to 144 seconds.

According to Monier-Williams, kāla 2 is from the verbal root kal "to calculate", while the root of kāla 1 is uncertain, though possibly the same.[3]

As a deity

As applied to gods and goddesses in works such as the Devī Māhātmya and the Skanda Purāṇa, kāla 1 and kāla 2 are not readily distinguishable. Thus Wendy Doniger, translating a conversation between Śiva and Pārvatī from the Skanda Purāṇa, says Mahākāla may mean " 'the Great Death' ... or 'the Great Black One' ".[4] And Swāmī Jagadīśvarānanda, a Hindu translator of the Devī Māhātmya, renders the feminine compound kāla-rātri (where rātri means "night") as "dark night of periodic dissolution".[5]

As Time personified, destroying all things, Kala is a god of death sometimes identified with Yama.

In the epics and the Puranas

Kala appears as an impersonal deity within the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and the Bhagavata Purana. In the Mahabharata, Krishna, one of the main characters, reveals his identity as Time personified. He states to Arjuna that both sides on the battlefield of the Kurukshetra War have already been annihilated. At the end of the epic, the entire Yadu dynasty (Krishna's family) is similarly annihilated.

Kala appears in the Uttara Kanda of the Ramayana, as the messenger of Death (Yama). At the end of the story, Time, in the form of inevitability or necessity, informs Rama that his reign on Earth is now over. By a trick or dilemma, he forces the death of Lakshmana, and informs Rama that he must return to the realm of the gods. Lakshmana willingly passes away with Rama's blessing and Rama returns to Heaven.

Time appears in the Bhagavata Purana as the force that is responsible for the imperceptible and inevitable change in the entire creation. According to the Purana, all created things are illusory, and thereby subject to creation and annihilation, this imperceptible and inconceivable impermanence is said to be due to the march of Time. Similarly, Time is considered to be the unmanifest aspect of God that remains after the destruction of the entire world at the end of a lifespan of Brahma.

In the Chaitanya Bhagavata, a Gaudiya Vaishnavist text and biography of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, it is said that the fire that emerges from the mouth of Sankarshana at the End of Time is the Kālānala, or "fire of Time".[6] One of the names of Sankarshana is kālāgni, also "fire of Time".[7]

The Vishnu Purana also states that Time (kala) is one of the four primary forms of Vishnu, the others being matter (Pradhana), visible substance (vyakta), and Spirit (Purusha).[8][9]

In the Bhagavad Gita

At Bhagavad Gita 11.32, Krishna takes on the form of kāla, the destroyer, announcing to Arjuna that all the warriors on both sides will be killed, apart from the Pandavas:

कालो ऽस्मि लोकक्षयकृत् प्रवृद्धो लोकान् समाहर्तुम् इह प्रवृत्तः ।

This verse means: "Time (kāla) I am, the great destroyer of the worlds, and I have come here to destroy all people."[10] This phrase is famous for being quoted by J. Robert Oppenheimer as he reflected on the Manhattan Project's explosion of the first nuclear bomb in 1945.

In other cultures

In Javanese mythology, Batara Kala is the god of destruction. It is a very huge mighty and powerful god depicted as giant, born of the sperm of Shiva, the kings of gods.

In Borobudur, the gate to the stairs is adorned with a giant head, making the gate look like the open mouth of the giant. Many other gates in Javanese traditional buildings have this kind of ornament. Perhaps the most detailed Kala Face in Java is on the south side of Candi Kalasan.

As a Substance

In Jainism, Kāla (Time) is infinite and is explained in two different ways:

- The measure of duration, known in the form of hours, days, like that.

- The cause of the continuity of function of things.

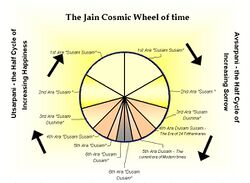

However Jainism recognizes a very small measurement of time known as samaya which is an infinitely small part of a second. There are cycles (kalachakras) in it. Each cycle having two eras of equal duration described as the avasarpini and the utsarpini.

See also

References

- ↑ Roshen Dalal (5 October 2011). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=DH0vmD8ghdMC&pg=PA185. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ Sanskrit and Tamil Dictionaries

- ↑ Sanskrit and Tamil Dictionaries

- ↑ Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy; Hindu Myths; Penguin, 1975; ISBN 0-14-044306-1 footnote to page 253.

- ↑ Jagadīśvarānanda trans; Devi Mahatmyam (Sanskrit and English); Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras, 1953; chapter 1 verse 78.

- ↑ Thakura, Vrndavana Dasa. Chaitanya-Bhagavata. Translated by Sarvabhavana Dasa. pp. 203.

- ↑ "A Thousand Names of Lord Balarama". http://www.stephen-knapp.com/thousand_names_of_lord_balarama.htm.

- ↑ Wilson, Horace H. (1840). "Preface". The Vishńu Puráńa: A System of Hindu Mythology and Tradition. pp. ix.

- ↑ Roy, Janmajit (2002). "Signs and Symptoms of Avatārahood". Theory of Avatāra and Divinity of Chaitanya. New Dehli: Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. pp. 66.

- ↑ See text and translation

KSF

KSF