List of NASA missions

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

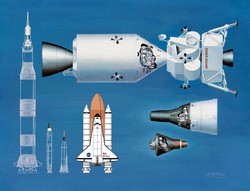

This is a list of NASA missions, both crewed and robotic, since the establishment of NASA in 1957. There are over 80 currently active science missions.[1]

X-Plane program

Since 1945, NACA (NASA's predecessor) and, since January 26, 1958, NASA has conducted the X-Plane Program. The program was originally intended to create a family of experimental aircraft not intended for production beyond the limited number of each design built solely for flight research.[2] The first X-Plane, the Bell X-1, was the first rocket-powered airplane to break the sound barrier on October 14, 1947.[3] X-Planes have set numerous milestones since then, both crewed and unpiloted.[4]

Human spaceflight

NASA has successfully launched 166 crewed flights. Three have ended in failure, causing the deaths of seventeen crewmembers in total: Apollo 1 (which never launched) killed three crew members in 1967, STS-51-L (the Challenger disaster) killed seven in 1986, and STS-107 (the Columbia disaster) killed seven more in 2003. Thus far, 163 missions were conducted without fatalities.

| Program | Start date | First crewed flight | End date | No. of crewed missions launched |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project Mercury | 1958 | 1961 | 1963 | 6 | First U.S. crewed program |

| Project Gemini | 1961 | 1965 | 1966 | 10 | Program used to practice space rendezvous and EVAs |

| Apollo program | 1960 | 1968 | 1972 | 11[a] | Landed first humans on the Moon |

| Skylab | 1964 | 1973 | 1974 | 3 | First American space station |

| Apollo–Soyuz | 1971 | 1975 | 1975 | 1 | Joint with Soviet Union |

| Space Shuttle program | 1972 | 1981 | 2011 | 135[b] | First missions in which a spacecraft was reused |

| Shuttle–Mir program | 1993 | 1994 | 1998 | 11[c] | Russian partnership |

| International Space Station | 1993 | 1998 | Ongoing | 65 | Joint with Roscosmos, CSA, ESA, and JAXA; Americans flew on Russian Soyuz after 2011 retirement of Space Shuttle |

| Commercial Crew Program | 2011 | 2020 | Ongoing | 8 | Current program to shuttle Americans to the ISS |

| Artemis program | 2017 | 2024 (Planned) | Ongoing | 0 | Current program to bring humans to the Moon again |

Notes:

- Apollo 1 was unlaunched due to a fire during testing that killed the astronauts, and is not counted here.

- Two Space Shuttle missions ended with the disintegrations of the vehicles and the deaths of two crews before reaching orbit and while returning from orbit.

- The Shuttle-Mir missions were all Space Shuttle missions, and are also counted under the Space Shuttle program missions in the table.

Canceled

In May 2009, the Obama Administration announced the launch of an independent review of planned U.S. human space flight activities with the goal of ensuring that the nation is on a vigorous and sustainable path to achieving its boldest aspirations in space. The review was conducted by a panel of experts led by Norman Augustine, the former CEO of Lockheed Martin, who served on the President's Council of Advisers on Science and Technology under both Democrat and Republican presidents.[5]

The "Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans" was to examine ongoing and planned National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) development activities, as well as potential alternatives and present options for advancing a safe, innovative, affordable, and sustainable human space flight program in the years following Space Shuttle retirement. The panel worked closely with NASA and sought input from the United States Congress, the White House, the public, industry, and international partners as it developed its options. It presented its results on October 22, 2009.[6][7] [8]

In February 2010, Obama announced his proposal to cancel the Constellation Program as part of the 2011 Economic Projects. Constellation was officially canceled by the NASA Budget Authorization Act on October 11, 2010.

Future

NASA brought the Orion spacecraft back to life from the defunct Constellation Program and successfully test-launched the first capsule on December 5, 2014, aboard EFT-1. After a near-perfect flight traveling 3,600 miles (5,800 km) above Earth, the spacecraft was recovered for study. NASA plans to use the Orion crew vehicle to send humans to deep space locations such as the Moon and Mars starting in the 2020s. Orion will be powered by NASA's new heavy-lift vehicle, the Space Launch System (SLS), which is currently under development.

Artemis 1 is the first flight of the SLS and was launched as a test of the completed Orion and SLS system.[9] During the mission, an uncrewed Orion capsule will spend 10 days in a distant retrograde 60,000 kilometers (37,000 mi) orbit around the Moon before returning to Earth.[10] Artemis 2, the first crewed mission of the program, will launch four astronauts in 2024[11] on a free-return flyby of the Moon at a distance of 8,900 kilometers (5,500 mi).[12][13][14]

After Artemis 2, the Power and Propulsion Element of the Lunar Gateway and three components of an expendable lunar lander are planned to be delivered on multiple launches from commercial launch service providers.[15]

Artemis 3 is planned to launch in 2025[16] aboard an SLS Block 1 rocket and will use the minimalist Gateway and expendable lander to achieve the first crewed lunar landing of the program. The flight is planned to touch down on the lunar south pole region, with two astronauts staying there for about one week.[15][17][18][19][20]

Robotic missions

Suborbital

- Anomalous Transport Rocket Experiment (ATREX) – five consecutive launches, 80 seconds apart on March 27, 2012, studied the high-altitude jet stream.[21][22]

- NASA Sounding Rocket Program

- SHIELDS – launched April 19, 2021, collected data from the heliopause.[23]

Earth and Heliocentric satellites

- Biosatellite 1, launched December 1966, completed

- Biosatellite 2, launched September 1967, completed

- Biosatellite 3, launched June 1969, completed

- Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE), launched November 1989, completed

- Earth Observing System[24]

- Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), launched September 1991, completed

- Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), launched March 2002, completed

- Gravity Recover and Climate Experiment - Follow-On (GRACE-FO), launched May 2018, operational

- NPOESS Preparatory Project (NPP) – National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS), launched October 2011, operational [25]

- Echo 1 and 2, launched August 1960 and January 1964, respectively, completed

- Great Observatories

- Hubble Space Telescope, launched April 1990, operational

- Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, launched April 1991, completed

- Chandra X-ray Observatory, launched July 1999, operational

- Spitzer Space Telescope, launched August 2003, completed

- James Webb Space Telescope, launched December 2021, operational[26][27]

- High Energy Astronomy Observatory 1 (HEAO 1), launched August 1977, completed

- Einstein Observatory (HEAO 2) launched November 1978, completed – first fully imaging X-ray telescope

- High Energy Astronomy Observatory 3 (HEAO 3), launched September 1979, completed

- Imager for Magnetopause-to-Aurora Global Exploration (IMAGE), launched March 2000, completed

- Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), launched January 1983, completed

- Jason-1, launched December 2001, completed[28]

- OSTM/Jason-2, launched June 2008, completed[29]

- Jason-3, launched January 2016, operational[30]

- Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory (SWIFT), launched November 2004, operational

- Landsat program[31]

- Landsat 1, launched July 1972, completed

- Landsat 2, launched January 1975, completed

- Landsat 3, launched March 1978, completed

- Landsat 4, launched July 1982, completed

- Landsat 5, launched March 1984, completed

- Landsat 6, launched October 1993, failed

- Landsat 7, launched April 1999, operational

- Landsat 8, launched February 2013, operational

- Landsat 9, launched September 2021, operational

- Van Allen Probes, launched August 2012, completed – Twin probes studying the Van Allen radiation belt[32][33]

- Terra, launched December 1999, operational

- Aqua, launched May 2002, operational

- Aura, launched July 2004, operational

- New Millennium Program (NMP)

- Earth Observing-1 (EO-1), launched November 2000, completed

- Space Technology 5 (ST5), launched March 2006, completed

- Space Technology 6 (ST6)

- NanoSail-D, launched August 2008, failed

- NanoSail-D2, launched November 2010, completed

- Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO), launched February 2009, failed

- Orbiting Carbon Observatory (OCO-2), launched July 2014, operational

- Origins program

- Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE), launched June 1999, completed

- Kepler, launched March 2009, completed – searching for Earth-sized exoplanets in the habitable zone

- Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms (THEMIS), launched February 2007, operational

- Small Explorer program (SMEX)[34]

- Aeronomy of Ice in the Mesosphere (AIM), launched April 2007, operational

- Fast Auroral Snapshot Explorer (FAST), launched August 1996, completed

- Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX), launched April 2003, completed

- Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX), launched October 2008, operational

- Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), launched June 2012, operational – X-ray telescope orbiting Earth[35][36]

- Reuven Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI), launched February 2002, completed – Sun observing, Earth satellite

- Solar Anomalous and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer (SAMPEX), launched July 1992, completed

- Submillimeter Wave Astronomy Satellite (SWAS), launched December 1998, completed

- Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE), launched August 1998, completed – Sun observing, Earth satellite

- Wide Field Infrared Explorer (WIRE), launched March 1999, failed

- Hinode (Solar-B)

- Thermosphere Ionosphere Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED)

- Two Wide-angle Imaging Neutral-atom Spectrometers (TWINS)

- Uhuru

- Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP)

- Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE)

- BioSentinel

- Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, launching May 2027, future

Sun

- Pioneer 6, 7, 8, and 9, launched between December 1965 and November 1968, completed – Solar wind, solar magnetic field and cosmic rays

- Helios 1 and 2, launched December 1974 and January 1976, completed

- Ulysses spacecraft, launched October 1990, completed – ESA partnership

- Genesis, launched August 2001, completed – returned sample of solar wind

- Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), launched December 1995, operational – ESA partnership

- Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), launched August 1997, operational

- Solar Maximum Mission (SolarMax), launched February 1980, completed – suffered partial failure after launch; repaired in April 1984 during a Space Shuttle mission

- Solar Terrestrial Probes program

- Parker Solar Probe, launched August 2018, operational – the first mission into the Sun's corona[38][39]

- Living With a Star

- Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), launched February 2010, operational

- Balloon Array for RBSP Relativistic Electron Losses (BARREL) – two campaigns of 20 balloons each, studying the Van Allen radiation belts, 2012 to 2014[40] This mission is a complement to the Van Allen Probes (RBSP).[41]

- CubeSat for Solar Particles (CuSP), launched November 2022

Moon

- Pioneer 0, launched August 1958, failed

- Pioneer 1, launched October 1958, failed

- Pioneer 2, launched November 1958, failed

- Pioneer 3, launched December 1958, failed

- Pioneer 4, launched March 1959, completed

- Pioneer P-1, launched September 1959, failed

- Pioneer P-3, launched November 1959, failed

- Pioneer P-30, launched September 1960, failed

- Pioneer P-31, launched December 1960, failed

- Ranger 1, launched August 1961, failed

- Ranger 2, launched November 1961, failed

- Ranger 3, launched January 1962, failed

- Ranger 4, launched April 1962, failed

- Ranger 5, launched October 1962, failed

- Ranger 6, launched January 1964, failed

- Ranger 7, launched July 1964, completed

- Ranger 8, launched February 1965, completed

- Ranger 9, launched March 1965, completed

- Surveyor 1, launched May 1966, completed

- Surveyor 2, launched September 1966, failed

- Surveyor 3, launched April 1967, completed

- Surveyor 4, launched July 1967, failed

- Surveyor 5, launched September 1967, completed

- Surveyor 6, launched November 1967, completed

- Surveyor 7, launched January 1968, completed

- Lunar Orbiter 1, launched August 1966, completed

- Lunar Orbiter 2, launched November 1966, completed

- Lunar Orbiter 3, launched February 1967, completed

- Lunar Orbiter 4, launched May 1967, completed

- Lunar Orbiter 5, launched August 1967, completed

- Clementine, launched January 1994, completed

- Discovery Program

- Discovery 3 – Lunar Prospector, launched January 1998, completed

- Discovery 11 – GRAIL, launched September 2011, completed [42]

- Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) – instrument for ISRO's Chandraayan-1, launched October 2008, completed

- Lunar Precursor Robotic Program (LPRP)

- LCROSS, launched June 2009, completed

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), launched June 2009, operational

- LADEE, launched September 2013, completed

- Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter's ShadowCam instrument, launched August 2022, operational

- CAPSTONE, launched November 2022, operational

- LunaH-Map, launched November 2022, operational

- Lunar IceCube, launched November 2022, operational

- Lunar Flashlight, launched December 2022, failed

- Commercial Lunar Payload Services

- Peregrine Mission One, launched January 2024, failed

Mercury

- Mariner 10, launched November 1973, completed – flyby of Venus; multiple flybys of Mercury; first spacecraft to Mercury

- Discovery program

Venus

- Mariner 1, launched July 1962, failed – intended to be first American flyby of Venus

- Mariner 2, launched August 1962, completed – first flyby of Venus by an operational spacecraft

- Mariner 5, launched June 1967, completed – flyby of Venus

- Mariner 10, launched November 1973, completed – flyby of Venus; multiple flybys of Mercury; first spacecraft to Mercury

- Pioneer 5, launched March 1960, completed – interplanetary space between Earth and Venus

- Pioneer Venus project

- Pioneer Venus Orbiter, launched May 1978, completed – Venus orbiter

- Pioneer Venus Multiprobe, launched August 1978, completed – Venus atmospheric probes

- Magellan, launched May 1989, completed – radar mapping of Venus

- Discovery Program

Mars

- Mariner 4, launched November 1964, completed

- Mariner 6 and 7, launched February 1969, completed

- Mariner 8, launched May 1971, failed

- Mariner 9, launched May 1971, completed

- Mars Observer, launched September 1992, failed

- Mars Global Surveyor, launched November 1996, completed

- Discovery Program

- Discovery 2 – Mars Pathfinder / Sojourner rover, launched July 1997, completed

- Discovery 12 – InSight, launched May 2018, completed

- Mars Polar Lander, launched January 1999, failed

- Deep Space 2, launched January 1999, failed – (sub-surface probes)

- 2001 Mars Odyssey, launched April 2001, operational

- Mars Exploration Rovers

- Spirit rover, launched June 2003, completed

- Opportunity rover, launched June 2003, completed

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, launched August 2005, operational – Mars orbiter

- Mars Scout program

- Phoenix, launched August 2007, completed – Mars lander

- MAVEN, launched November 2013, operational – orbiter studying the atmosphere of Mars

- Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) / Curiosity rover, launched November 2011, operational – Mars rover exploring Gale Crater

- InSight, launched May 2018, completed

- Mars 2020

- Perseverance rover, launched July 2020, operational – Mars rover exploring Jezero Crater

- Ingenuity helicopter, launched July 2020, completed – first powered flight on Mars

- EscaPADE, launching August 2024, future

- NASA-ESA Mars Sample Return, launching 2027 and 2028, future

Jupiter

- Pioneer 10, launched March 1972, completed – first to the asteroid belt and Jupiter

- Pioneer 11, launched December 1974, completed – asteroid belt and Jupiter, first to Saturn

- Voyager 1, launched September 1977, operational – flybys of Jupiter and Saturn; extended mission to explore interstellar medium; most distant human-made object

- Voyager 2, launched August 1977, operational – flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; extended mission to explore interstellar medium; first spacecraft to Uranus and Neptune

- Galileo, launched October 1989, completed – Jupiter and its moons

- New Frontiers program

- Europa Clipper, launching 2024, future

Saturn

- Pioneer 11, launched December 1974, completed – asteroid belt and Jupiter, first to Saturn

- Voyager 1, launched September 1977, operational – flybys of Jupiter and Saturn; extended mission to explore interstellar medium; most distant human-made object

- Voyager 2, launched August 1977, operational – flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune; extended mission to explore interstellar medium; first spacecraft to Uranus and Neptune

- Cassini–Huygens, launched October 1997, completed – Saturn and its moons

- New Frontiers program

- New Frontiers 4 – Dragonfly, launching 2027, future

- Enceladus Orbilander, launching 2038, future

Uranus

- Uranus Orbiter and Probe, launching 2032, future

Neptune

Asteroids/comets

- New Millennium Program (NMP)

- NEAR Shoemaker, launched February 1996, completed – close study of 433 Eros

- Deep Space 1 (DS1), launched October 1998, completed – first spacecraft propelled by an ion thruster

- Discovery 4 – Stardust, launched February 1999, completed – follow-up for Deep Impact's primary mission to 9P/Tempel

- Discovery 6 – CONTOUR, launched July 2002, failed

- Discovery 8 – Deep Impact (primary); EPOXI (extended), launched January 2005, completed

- Discovery 13 – Lucy, launched October 2021, operational – Will fly by one main-belt asteroid and seven Jupiter Trojan asteroids.[44]

- Discovery 14 – Psyche, launched October 2023, enroute

- New Frontiers 3 – OSIRIS-REx – launched September 2016, operational[45][46]

- Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), launched November 2021, completed

- Near-Earth Asteroid Scout, launched November 2022, failed

Dwarf planets

- New Frontiers 1 – New Horizons, launched January 2006, operational – flyby of Pluto and its moons in 2015; first to Pluto

Canceled or undeveloped missions

- Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby (CRAF)

- Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JIMO)

- Mars Astrobiology Explorer-Cacher (MAX-C)

- Mars Telecommunications Orbiter (MTO)

- Asteroid Redirect Mission (2013-2017)

- Origins Program

- Pluto Kuiper Express (PLUTOKE) – replaced by New Horizons

Old proposals

- Mars Scout program

- Aerial Regional-scale Environmental Survey (ARES) (2000-2010 concept)

- TAU (spacecraft)- probe to 1000 AU (1980s concept)

See also

- NASA:

- Large strategic science missions, the NASA flagship missions

- Discovery Program, medium-cost NASA missions

- New Frontiers program, medium-large NASA missions to outer planets

- When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions – 2008 documentary covering NASA's mission history.

- Space exploration

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- List of European Space Agency programmes and missions

References

- ↑ "NASA Science Missions | Science Mission Directorate". https://science.nasa.gov/missions-page?field_division_tid=All&field_phase_tid=29.

- ↑ "Dryden Historic Aircraft - X-planes overview". Dryden Flight Research Center. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/dryden/history/HistoricAircraft/X-Planes/1940/index.html.

- ↑ "Bell X-1 "Glamorous Glennis"". Milestones of Flight. National Air and Space Museum. http://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/gal100/bellx1.html.

- ↑ "APPENDIX A; HISTORY OF THE X-PLANE PROGRAM". Draft X-33 Environmental Impact Statement. NASA. https://history.nasa.gov/x1/appendixa1.html.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (January 20, 2017). "President Obama's Space Legacy: Mars, Private Spaceflight and More". Space.com. https://www.space.com/35394-president-obama-spaceflight-exploration-legacy.html.

- ↑ "OSTP Press Release Announcing Review (pdf, 50k)". http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/358006main_OSTP%20Press%20Release.pdf.

- ↑ "No to NASA: Augustine Commission Wants to More Boldly Go". http://news.sciencemag.org/scienceinsider/2009/10/no-nasa-augusti.html.

- ↑ "House Gives Final Approval to NASA Authorization Act". SpaceNews. September 30, 2010. https://spacenews.com/house-gives-final-approval-nasa-authorization-act/.

- ↑ Foust 2019, "Artemis 1, or EM-1, will be an uncrewed test flight of Orion and SLS and is scheduled to launch in June of 2020."

- ↑ Heaton & Sood 2020, p. 3.

- ↑ "NASA's Artemis 2 mission around Moon set for November 2024". Phys.org. 7 March 2023. https://phys.org/news/2023-03-nasa-artemis-mission-moon-november.html.

- ↑ Hambleton, Kathryn (2018-08-27). "First Flight With Crew Important Step on Long-Term Return to Moon". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-first-flight-with-crew-important-step-on-long-term-return-to-the-moon-missions-to.

- ↑ Hambleton, Kathryn (2019-05-23). "NASA's First Flight With Crew Important Step on Long-term Return to the Moon, Missions to Mars". https://www.nasa.gov/feature/nasa-s-first-flight-with-crew-important-step-on-long-term-return-to-the-moon-missions-to.

- ↑ Heaton & Sood 2020, p. 7.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Weitering, Hanneke (May 23, 2019). "NASA Has a Full Plate of Lunar Missions Before Astronauts Can Return to Moon". https://www.space.com/nasa-moon-missions-before-2024.html. "And before NASA sends astronauts to the moon in 2024, the agency will first have to launch five aspects of the lunar Gateway, all of which will be commercial vehicles that launch separately and join each other in lunar orbit. First, a power and propulsion element will launch in 2022. Then, the crew module will launch (without a crew) in 2023. In 2024, during the months leading up to the crewed landing, NASA will launch the last critical components: a transfer vehicle that will ferry landers from the Gateway to a lower lunar orbit, a descent module that will bring the astronauts to the lunar surface, and an ascent module that will bring them back up to the transfer vehicle, which will then return them to the Gateway."

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (13 March 2023). "NASA planning to spend up to $1 billion on space station deorbit module". SpaceNews. https://spacenews.com/nasa-planning-to-spend-up-to-1-billion-on-space-station-deorbit-module/.

- ↑ Grush 2019, "Now, for Artemis 3 that carries our crew to the Gateway, we need to have the crew have access to a lander. So, that means that at Gateway we're going to have the Power and Propulsion Element, which will be launched commercially, the Utilization Module, which will be launched commercially, and then we'll have a lander there..

- ↑ Grush 2019, "The direction that we have right now is that the next man and the first woman will be Americans and that we will land on the south pole of the Moon in 2024.".

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (May 25, 2019). "For Artemis Mission to Moon, NASA Seeks to Add Billions to Budget". https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/science/trump-nasa-moon-mars.html. "Under the NASA plan, a mission to land on the moon would take place during the third launch of the Space Launch System. Astronauts, including the first woman to walk on the moon, Mr. Bridenstine said, would first stop at the orbiting lunar outpost. They would then take a lander to the surface near its south pole, where frozen water exists within the craters."

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (July 21, 2019). "NASA outlines plans for lunar lander development through commercial partnerships". SpaceNews. https://spacenews.com/nasa-outlines-plans-for-lunar-lander-development-through-commercial-partnerships/.

- ↑ "Anomalous Transport Rocket Experiment (ATREX)". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/missions/atrex.html.

- ↑ "ATREX Launch Sequence". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/627738main_atrex-launch-sequence.pdf.

- ↑ "SHIELDS Up! NASA Rocket to Survey Our Solar System's Windshield". April 15, 2021. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2021/shields-up-nasa-rocket-to-survey-our-solar-system-s-windshield.

- ↑ "Missions – Science Mission Directorate". https://science.nasa.gov/earth-science/missions/.

- ↑ "NPP Launch Information". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/NPP/launch/index.html.

- ↑ "JWST Home Page". NASA. http://www.jwst.nasa.gov/.

- ↑ "10-Year Plan for Astrophysics Takes JWST Cost into Account". SpaceNews.com. 2010-08-20. http://www.spacenews.com/civil/100820-plan-astrophysics-jwst-account.html.

- ↑ "Jason-1". https://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/jason1/.

- ↑ "OSTM/Jason-2". https://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/ostmjason2/.

- ↑ "Jason 3". https://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/jason3./

- ↑ "Landsat Missions Timeline – Landsat Missions". http://landsat.usgs.gov/about_mission_history.php.

- ↑ "RBSP Mission Overview". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/rbsp/.

- ↑ "RBSP". NASA/APL. http://rbsp.jhuapl.edu/.

- ↑ "Explorer Missions". NASA. http://explorers.gsfc.nasa.gov/missions.html.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (2012-04-03). "Launch of NASA X-ray telescope targeted for June". Spaceflight Now. http://spaceflightnow.com/pegasus/nustar/120403june/.

- ↑ "NuSTAR". NASA. 2012-06-05. https://science.nasa.gov/missions/nustar/.

- ↑ "MMS Launch". NASA. 2013-11-06. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/mms/launch/index.html.

- ↑ "NASA Selects Science Investigations for Solar Probe Plus". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/topics/solarsystem/sunearthsystem/main/solarprobeplus.html.

- ↑ "Johns Hopkins APL Team Developing Solar Probe Plus for Closest-Ever Flights Past the Sun". JHU APL. http://jhuapl.edu/newscenter/pressreleases/2012/120305.asp.

- ↑ Karen C. Fox (2011-02-22). "Launching Balloons in Antarctica". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sunearth/news/barrel-antarctica.html.

- ↑ "Van Allen Probes: NASA Renames Radiation Belt Mission to Honor Pioneering Scientist". Reuters. Science Daily. November 11, 2012. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/11/121111101748.htm.

- ↑ "GRAIL Mission: Fact Sheet". MoonKAM.UCSD.edu. https://moonkam.ucsd.edu/about/grail_fact_sheet.

- ↑ "Juno Mission to Jupiter". NASA. April 2009. pp. 2. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/316306main_JunoFactSheet_2009sm.pdf.

- ↑ "NASA, ULA Launch Lucy Mission to 'Fossils' of Planet Formation" (Press release). NASA. October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "NASA To Launch New Science Mission To Asteroid In 2016". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2011/may/HQ_11-163_New_Frontier.html.

- ↑ "NASA's OSIRIS-REx Speeds Toward Asteroid Rendezvous". NASA. 2016-09-08. https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-s-osiris-rex-speeds-toward-asteroid-rendezvous.

Bibliography

- Grush, Loren (May 17, 2019). "NASA administrator on new Moon plan: ‘We’re doing this in a way that’s never been done before’". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/5/17/18627839/nasa-administrator-jim-bridenstine-artemis-moon-program-budget-amendment.

- Heaton, Andrew; Sood, Dr. Rohan (August 10, 2020). "Space Launch System Departure Trajectory Analysis for Cislunar and Deep-Space Exploration". NASA. p. 7. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20205005206/downloads/20205005206%20OCR%20reupload.pdf.

External links

|

KSF

KSF