List of quasars

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

This article contains lists of quasars. More than a million quasars have been observed,[1] so any list on Wikipedia is necessarily a selection of them.

Proper naming of quasars are by Catalogue Entry, Qxxxx±yy using B1950 coordinates, or QSO Jxxxx±yyyy using J2000 coordinates. They may also use the prefix QSR. There are currently no quasars that are visible to the naked eye.

List of quasars

This is a list of exceptional quasars for characteristics otherwise not separately listed

| Quasar | Notes |

|---|---|

| Twin Quasar | Associated with a possible planet microlensing event in the gravitational lens galaxy that is doubling the Twin Quasar's image. |

| QSR J1819+3845 | Proved interstellar scintillation due to the interstellar medium. |

| CTA-102 | In 1965, Soviet astronomer Nikolai S. Kardashev declared that this quasar was sending coded messages from an alien civilization.[2] |

| CID-42 | Its supermassive black hole is being ejected and will one day become a displaced quasar. |

| TON 618 | TON 618 is a very distant and extremely luminous quasar—technically, a hyperluminous, broad-absorption line, radio-loud quasar—located near the North Galactic Pole in the constellation Canes Venatici. |

List of named quasars

This is a list of quasars, with a common name, instead of a designation from a survey, catalogue or list.

| Quasar | Origin of name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Twin Quasar | From the fact that two images of the same gravitationally lensed quasar is produced. | |

| Einstein Cross | From the fact that gravitational lensing of the quasar forms a near perfect Einstein cross, a concept in gravitational lensing. | |

| Triple Quasar | From the fact that there are three bright images of the same gravitationally lensed quasar. | There are actually four images; the fourth is faint. |

| Cloverleaf | From its appearance having similarity to the leaf of a clover. It has been gravitationally lensed into four images, of roughly similar appearance. | |

| Teacup Galaxy | The name comes from the shape of the extended emission, which is shaped like the handle of a teacup. The handle is a bubble shaped by quasar winds or small-scale radio jets. | Low redshift, highly obscured type 2 quasar. |

List of multiply imaged quasars

This is a list of quasars that as a result of gravitational lensing appear as multiple images on Earth.

| Quasar | Images | Lens | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twin Quasar | 2 | YGKOW G1 | First gravitationally lensed object discovered |

| Triple Quasar (PG 1115+080) | 4 | Originally discovered as 3 lensed images, the fourth image is faint. It was the second gravitationally lensed quasar discovered. | |

| Einstein Cross | 4 | Huchra's Lens | First Einstein Cross discovered |

| RX J1131-1231's quasar | 4 | RX J1131-1231's elliptical galaxy | RX J1131-1231 is the name of the complex, quasar, host galaxy and lensing galaxy, together. The quasar's host galaxy is also lensed into a Chwolson ring about the lensing galaxy. The four images of the quasar are embedded in the ring image. |

| Cloverleaf | 4[3] | Brightest known high-redshift source of CO emission[4] | |

| QSO B1359+154 | 6 | CLASS B1359+154 and three more galaxies | First sextuply-imaged galaxy |

| SDSS J1004+4112 | 5 | Galaxy cluster at z = 0.68 | First quasar discovered to be multiply image-lensed by a galaxy cluster and currently the third largest quasar lens with the separation between images of 15″[5][6][7] |

| SDSS J1029+2623 | 3 | Galaxy cluster at z = 0.6 | The current largest-separation quasar lens with 22.6″ separation between furthest images[8][9][10] |

| SDSS J2222+2745 | 6[11] | Galaxy cluster at z = 0.49[12] | First sextuply-lensed galaxy[11] Third quasar discovered to be lensed by a galaxy cluster.[12] Quasar located at z = 2.82[12] |

List of visual quasar associations

This is a list of double quasars, triple quasars, and the like, where quasars are close together in line-of-sight, but not physically related.

| Quasars | Count | Notes |

|---|---|---|

QSO 1548+115

|

2 | [13][14] |

| QSO 1146+111 | 8 | [15] |

| z represents redshift, a measure of recessional velocity and inferred distance due to cosmological expansion | ||

List of physical quasar groups

This is a list of binary quasars, trinary quasars, and the like, where quasars are physically close to each other.

| Quasars | Count | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| quasars of SDSS J0841+3921 protocluster | 4 | First quasar quartet discovered.[16][17] |

| LBQS 1429-008 (QQQ 1432-0106) | 3 | First quasar triplet discovered. It was first discovered as a binary quasar, before the third quasar was found.[18] |

QQ2345+007 (Q2345+007)

|

2 | Originally thought to be a doubly imaged quasar, but actually a quasar couplet.[19] |

| QQQ J1519+0627 | 3 | [20] |

Large Quasar Groups

Large quasar groups (LQGs) are bound to a filament of mass, and not directly bound to each other.

| LQG | Count | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Webster LQG (LQG 1) |

5 | First LQG discovered. At the time of its discovery, it was the largest structure known.[21][22] |

| Huge-LQG (U1.27) |

73 | The largest structure known in the observable universe, as of 2013.[23][24] |

List of quasars with apparent superluminal jet motion

This is a list of quasars with jets that appear to be superluminal due to relativistic effects and line-of-sight orientation. Such quasars are sometimes referred to as superluminal quasars.

| Quasar | Superluminality | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3C 279 | 4c | First quasar discovered with superluminal jets[25][26][27][28][29] |

| 3C 179 | 7.6c | Fifth discovered, first with double lobes[30] |

| 3C 273 | This is also the first quasar ever identified[31] | |

| 3C 216 | ||

| 3C 345 | [31][32] | |

| 3C 380 | ||

| 4C 69.21 (Q1642+690, QSO B1642+690) |

||

| 8C 1928+738 (Q1928+738, QSO J1927+73, Quasar J192748.6+735802) |

||

| PKS 0637-752 | ||

| QSO B1642+690 |

Quasars that have a recessional velocity greater than the speed of light (c) are very common. Any quasar with z > 1 is receding faster than c, while z exactly equal to 1 indicates recession at the speed of light.[33] Early attempts to explain superluminal quasars resulted in convoluted explanations with a limit of z = 2.326, or in the extreme z < 2.4.[34] The majority of quasars lie between z = 2 and z = 5.

Firsts

| Title | Quasar | Year | Data | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First quasar discovered | 3C 48 | 1960 | first radio source for which optical identification was found, that was a star-like looking object | |

| First "star" discovered later found to be a quasar | ||||

| First radio source discovered later found to be a quasar | ||||

| First quasar identified | 3C 273 | 1962 | first radio-"star" found to be at a high redshift with a non-stellar spectrum. | |

| First radio-quiet quasar | QSO B1246+377 (BSO 1) | 1965 | The first radio-quiet quasi-stellar objects (QSO) were called Blue Stellar Objects or BSO, because they appeared like stars and were blue in color. They also had spectra and redshifts like radio-loud quasi-stellar radio-sources (QSR), so became quasars.[27][35][36] | |

| First host galaxy of a quasar discovered | 3C 48 | 1982 | ||

| First quasar found to seemingly not have a host galaxy | HE0450-2958 (Naked Quasar) | 2005 | Some disputed observations suggest a host galaxy, others do not. | |

| First multi-core quasar | PG 1302-102 | 2014 | Binary supermassive black holes within the quasar | [37][38] |

| First quasar containing a recoiling supermassive black hole | SDSS J0927+2943 | 2008 | Two optical emission line systems separated by 2650 km/s | |

| First gravitationally lensed quasar identified | Twin Quasar | 1979 | Lensed into 2 images | The lens is a galaxy known as YGKOW G1 |

| First quasar found with a jet with apparent superluminal motion | 3C 279 | 1971 | [25][26][27] | |

| First quasar found with the classic double radio-lobe structure | 3C 47 | 1964 | ||

| First quasar found to be an X-ray source | 3C 273 | 1967 | [39] | |

| First "dustless" quasar found | QSO J0303-0019 and QSO J0005-0006 | 2010 | [40][41][42][43][44][45][46] | |

| First Large Quasar Group discovered | Webster LQG (LQG 1) |

1982 | [21][22] |

Extremes

| Title | Quasar | Data | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brightest | 3C 273 | Apparent magnitude of ~12.9 | Absolute magnitude: −26.7 |

| Seemingly optically brightest | APM 08279+5255 | Seeming absolute magnitude of −32.2 | This quasar is gravitationally lensed; its actual absolute magnitude is estimated to be −30.5 |

| Most luminous | SMSS J215728.21-360215.1 | Absolute magnitude of −32.36 | Highest absolute magnitude discovered thus far. |

| Most powerful quasar radio source | 3C 273 | Also the most powerful radio source in the sky | |

| Most powerful | SMSS J215728.21-360215.1 | ||

| Most variable quasar radio source | QSO J1819+3845 (Q1817+387) | Also the most variable extrasolar radio source | |

| Least variable quasar radio source | |||

| Most variable quasar optical source | |||

| Least variable quasar optical source | |||

| Most distant | UHZ1 | z = 10.1 | Most distant quasar known as of 2023[47] |

| Most distant radio-quiet quasar | |||

| Most distant radio-loud quasar | QSO J1427+3312 | z = 6.12 | Found June 2008[48][49] |

| Most distant blazar quasar | PSO J0309+27 | z > 6 | |

| Least distant | Markarian 231 | 600 Mly | [50] inactive: IC 2497 |

| Largest Large Quasar Group | Huge-LQG (U1.27) |

73 quasars | [23][24] |

First quasars found

| Rank | Quasar | Date of discovery | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3C 273 | 1963 | [51] |

| 2 | 3C 48 | 1963 | [51] |

| 3 | 3C 47 | 1964 | [51] |

| 3 | 3C 147 | 1964 | [51] |

| 5 | CTA 102 | 1965 | [52] |

| 5 | 3C 287 | 1965 | [52] |

| 5 | 3C 254 | 1965 | [52] |

| 5 | 3C 245 | 1965 | [52] |

| 5 | 3C 9 | 1965 | [52] |

|

These are the first quasars which were found and had their redshifts determined. | |||

Most distant quasars

In 1964 a quasar became the most distant object in the universe for the first time. Quasars would remain the most distant objects in the universe until 1997, when a pair of non-quasar galaxies would take the title (galaxies CL 1358+62 G1 & CL 1358+62 G2 lensed by galaxy cluster CL 1358+62).[53]

In cosmic scales distance is usually indicated by redshift (denoted by z) which is a measure of recessional velocity and inferred distance due to cosmological expansion.

| Quasar | Distance | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

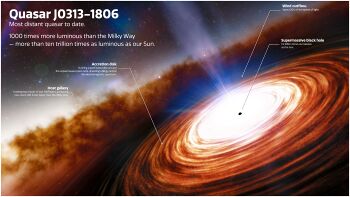

| QSO J0313–1806 | z = 7.64 | Currently the most distant known quasar.[55] | |

| ULAS J1342+0928 | z = 7.54 | Former most distant quasar. | |

| J1007+2115 (Pōniuāʻena) | z = 7.52 | ||

| ULAS J1120+0641 (ULAS J112001.48+064124.3) |

z = 7.085 | Former most distant quasar. First quasar with z > 7.[56] | |

| CHFQS J2348-3054 (CHFQS J234833.34-305410.0) |

z = 6.90 | ||

| PSO J172.3556+18.7734 | z = 6.82 | Currently the most distant radio-loud known quasar | |

| CFHQS J2329-0301 (CFHQS J232908-030158) |

z = 6.43 | Former most distant quasar.[57][58][59][60] | |

| SDSS J114816.64+525150.3 (SDSS J1148+5251) |

z = 6.419 | Former most distant quasar.[61][62][63][60][64][65] | |

| SDSS J1030+0524 (SDSSp J103027.10+052455.0) |

z = 6.28 | Former most distant quasar. First quasar with z > 6.[66][64][67][68][69][70][71] | |

| SDSS J104845.05+463718.3 (QSO J1048+4637) |

z = 6.23 | [65] | |

| SDSS J162331.81+311200.5 (QSO J1623+3112) |

z = 6.22 | [65] | |

| CFHQS J0033-0125 (CFHQS J003311-012524) |

z = 6.13 | [58] | |

| SDSS J125051.93+313021.9 (QSO J1250+3130) |

z = 6.13 | [65] | |

| CFHQS J1509-1749 (CFHQS J150941-174926) |

z = 6.12 | [58] | |

| QSO B1425+3326 / QSO J1427+3312 | z = 6.12 | Most distant radio-quasar.[48][72] | |

| SDSS J160253.98+422824.9 (QSO J1602+4228) |

z = 6.07 | [65] | |

| SDSS J163033.90+401209.6 (QSO J1630+4012) |

z = 6.05 | [65] | |

| CFHQS J1641+3755 (CFHQS J164121+375520) |

z = 6.04 | [58] | |

| SDSS J113717.73+354956.9 (QSO J1137+3549) |

z = 6.01 | [65] | |

| SDSS J081827.40+172251.8 (QSO J0818+1722) |

z = 6.00 | [65] | |

| SDSSp J130608.26+035626.3 (QSO J1306+0356) |

z = 5.99 | [69][70][71] | |

| |||

| Type | Quasar | Date | Distance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most distant | QSO J0313–1806 | 2021 | z = 7.64 | [55] |

| Most distant radio loud quasar | QSO B1425+3326 / QSO J1427+3312 | 2008 | z = 6.12 | |

| Most distant radio quiet quasar | ||||

| Most distant OVV quasar |

| Quasar | Date | Distance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSO J0313–1806 | 2021–present | z = 7.64 | Current record holder.[55] |

| ULAS J1342+0928 | 2017–2021 | z = 7.54 | [73] |

| ULAS J1120+0641 | 2011–2017 | z = 7.085 | Not the most distant object when discovered. First quasar with z > 7.[56] |

| CFHQS J2329-0301 (CFHQS J232908-030158) |

2007–2011 | z = 6.43 | Not the most distant object when discovered. It did not exceed IOK-1 (z = 6.96), which was discovered in 2006.[57][58][59][60][74][75][76] |

| SDSS J114816.64+525150.3 (SDSS J1148+5251) |

2003–2007 | z = 6.419 | Not the most distant object when discovered. It did not exceed HCM 6A galaxy lensed by Abell 370 at z = 6.56, discovered in 2002. Also discovered around the time of discovery was a new most distant galaxy, SDF J132418.3+271455 at z = 6.58.[61][62][63][60][74][77][78][79][80][81] |

| SDSS J1030+0524 (SDSSp J103027.10+052455.0) |

2001–2003 | z = 6.28 | Most distant object when discovered. First object with z > 6.[66][64][67][68][70][71] |

| SDSS 1044-0125 (SDSSp J104433.04-012502.2) |

2000–2001 | z = 5.82 | Most distant object when discovered. It exceeded galaxy SSA22-HCM1 (z = 5.74; discovered in 1999) as the most distant object.[82][83][70][71][74][84][85] |

| RD300 (RD J030117+002025) |

2000 | z = 5.50 | Not the most distant object when discovered. It did not surpass galaxy SSA22-HCM1 (z = 5.74; discovered in 1999).[86][87][83][88][74] |

| SDSSp J120441.73−002149.6 (SDSS J1204-0021) |

2000 | z = 5.03 | Not the most distant object when discovered. It did not surpass galaxy SSA22-HCM1 (z = 5.74; discovered in 1999).[88][74] |

| SDSSp J033829.31+002156.3 (QSO J0338+0021) |

1998–2000 | z = 5.00 | First quasar discovered with z > 5. Not the most distant object when discovered. It did not surpass galaxy BR1202-0725 LAE (z = 5.64; discovered earlier in 1998).[74][82][89][90][91][92][93] |

| PC 1247+3406 | 1991–1998 | z = 4.897 | Most distant object when discovered.[82][94][95][96][97] |

| PC 1158+4635 | 1989–1991 | z = 4.73 | Most distant object when discovered.[82][97][98][99][100][101] |

| Q0051-279 | 1987–1989 | z = 4.43 | Most distant object when discovered.[102][98][101][103][104][105] |

| Q0000-26 (QSO B0000-26) |

1987 | z = 4.11 | Most distant object when discovered.[102][98][106] |

| PC 0910+5625 (QSO B0910+5625) |

1987 | z = 4.04 | Most distant object when discovered; second quasar with z > 4.[82][98][107][108] |

| Q0046–293 (QSO J0048-2903) |

1987 | z = 4.01 | Most distant object when discovered; first quasar with z > 4.[102][98][107][109][110] |

| Q1208+1011 (QSO B1208+1011) |

1986–1987 | z = 3.80 | Most distant object when discovered and a gravitationally-lensed double-image quasar. From the time of discovery to 1991, had the least angular separation between images, 0.45″.[107][111][112] |

| PKS 2000-330 (QSO J2003-3251, Q2000-330) |

1982–1986 | z = 3.78 | Most distant object when discovered.[33][107][113][114] |

| OQ172 (QSO B1442+101) |

1974–1982 | z = 3.53 | Most distant object when discovered.[115][116][117] |

| OH471 (QSO B0642+449) |

1973–1974 | z = 3.408 | Most distant object when discovered; first quasar with z > 3. Nicknamed "the blaze marking the edge of the universe".[115][117][118][119][120] |

| 4C 05.34 | 1970–1973 | z = 2.877 | Most distant object when discovered. The redshift was so much greater than the previous record that it was believed to be erroneous, or spurious.[33][34][117][121][122] |

| 5C 02.56 (7C 105517.75+495540.95) |

1968–1970 | z = 2.399 | Most distant object when discovered.[122][123][53] |

| 4C 25.05 (4C 25.5) |

1968 | z = 2.358 | Most distant object when discovered.[122][53][124] |

| PKS 0237-23 (QSO B0237-2321) |

1967–1968 | z = 2.225 | Most distant object when discovered.[33][124][125][126][127] |

| 4C 12.39 (Q1116+12, PKS 1116+12) |

1966–1967 | z = 2.1291 | Most distant object when discovered.[53][127][128][129] |

| 4C 01.02 (Q0106+01, PKS 0106+1) |

1965–1966 | z = 2.0990 | Most distant object when discovered.[53][127][128][130] |

| 3C 9 | 1965 | z = 2.018 | Most distant object when discovered; first quasar with z > 2.[2][35][127][131][132][133] |

| 3C 147 | 1964–1965 | z = 0.545 | First quasar to become the most distant object in the universe, beating radio galaxy 3C 295.[134][135][136][137] |

| 3C 48 | 1963–1964 | z = 0.367 | Second quasar redshift measured. Redshift was discovered after publication of 3C273's results prompted researchers to re-examine spectroscopic data. Not the most distant object when discovered. The radio galaxy 3C 295 was found in 1960 with z = 0.461.[27][33][138][139][140][51][134] |

| 3C 273 | 1963 | z = 0.158 | First quasar redshift measured. Not the most distant object when discovered. The radio galaxy 3C 295 was found in 1960 with z = 0.461.[27][51][139][140][141] |

Most powerful quasars

| Rank | Quasar | Data | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SMSS J215728.21-360215.1 | It has an intrinsic bolometric luminosity of ~ 6.9 × 1014 Suns or ~ 2.6 × 1041 watts | [142] |

| 2 | HS 1946+7658 | It has an intrinsic bolometric luminosity in excess of 1014 Suns or 1041 watts | [143][144] |

| 3 | SDSS J155152.46+191104.0 | Has over 1041 watts luminosity | [145][146] |

| 4 | HS 1700+6416 | Has a luminosity of over 1041 watts | [147] |

| 5 | SDSS J010013.02+280225.8 | Has a luminosity of around 1.62 × 1041 watts | [148] |

| 6 | SBS 1425+606 | Has a luminosity of over 1041 watts – optically brightest for z>3 | [149] |

| J1144-4308 | Has a luminosity of 4.7 x 1040 watts or M_i(z=2) = -29.74 mag, optically brightest in last 9 Gyr | [150] | |

| SDSS J074521.78+473436.2 | [151][152] | ||

| S5 0014+813 | |||

| SDSS J160455.39+381201.6 | z = 2.51, M(i) = 15.84 | ||

| SDSS J085543.40-001517.7 | [153] |

See also

References

- ↑ Subir Sarkar (Jan 20, 2021). "Re-examining cosmic acceleration". Sommerfeld Theory Colloquium, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. p. 41. https://www.physik.uni-muenchen.de/aus_der_fakultaet/kolloquien/asc_kolloquium/archiv_wise20/sarkar/sarkar_reexamcosmicaccn.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Toward the Edge of the Universe". Time Magazine. May 21, 1965. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,901720,00.html.

- ↑ Magain, P.; Surdej, J.; Swings, J.-P.; Borgeest, U.; Kayser, R. (1988). "Discovery of a quadruply lensed quasar - The 'clover leaf' H1413 + 117". Nature 334 (6180): 325–327. doi:10.1038/334325a0. Bibcode: 1988Natur.334..325M.

- ↑ Venturini, S.; Solomon, P. M. (2003). "The Molecular Disk in the Cloverleaf Quasar". The Astrophysical Journal 590 (2): 740–745. doi:10.1086/375050. Bibcode: 2003ApJ...590..740V.

- ↑ Inada, N. (2003). "A Gravitationally lensed quasar with quadruple images separated by 14.62 arcseconds". Nature 426 (6968): 810–812. doi:10.1038/nature02153. PMID 14685230. Bibcode: 2003Natur.426..810I.

- ↑ Oguri, M. (2004). "Observations and Theoretical Implications of the Large-Separation Lensed Quasar SDSS J1004+4112". The Astrophysical Journal 605 (1): 78–97. doi:10.1086/382221. Bibcode: 2004ApJ...605...78O.

- ↑ Inada, N. (2005). "Discovery of a Fifth Image of the Large Separation Gravitationally Lensed Quasar SDSS J1004+4112". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 57 (3): L7–L10. doi:10.1093/pasj/57.3.L7. Bibcode: 2005PASJ...57L...7I.

- ↑ Inada, Naohisa (2006). "SDSS J1029+2623: A Gravitationally Lensed Quasar with an Image Separation of 22."5". The Astrophysical Journal 653 (2): L97–L100. doi:10.1086/510671. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...653L..97I.

- ↑ Oguri, Masamune (2008). "The Third Image of the Large-Separation Lensed Quasar SDSS J1029+2623". The Astrophysical Journal 676 (1): L1–L4. doi:10.1086/586897. Bibcode: 2008ApJ...676L...1O.

- ↑ Kratzer, Rachael M (2011). "Analyzing the Flux Anomalies of the Large-Separation Lensed Quasar SDSS J1029+2623". The Astrophysical Journal 728 (1): L18. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/728/1/L18. Bibcode: 2011ApJ...728L..18K.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 ScienceDaily, "Quasar Observed in Six Separate Light Reflections", 7 August 2013

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Dahle, H. (2013). "SDSS J2222+2745: A Gravitationally Lensed Sextuple Quasar with a Maximum Image Separation of 15.1″ Discovered in the Sloan Giant Arcs Survey". The Astrophysical Journal 773 (2): 146. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/773/2/146. Bibcode: 2013ApJ...773..146D.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : QSO 1548+115

- ↑ Burke, Bernard F. (1986). "Gravitational lenses - Observations". Quasars, Proceedings of the IAU Symposium, Bangalore, India, 2–6 December 1985. 119. D. Reidel Publishing Co.. 517. Bibcode: 1986IAUS..119..517B.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : QSO 1146+111

- ↑ Space Daily, "Astronomers Baffled by Discovery of Rare Quasar Quartet", 18 May 2015

- ↑ Hennawi, Joseph F.; Prochaska, J. Xavier; Cantalupo, Sebastiano; Arrigoni-Battaia, Fabrizio (15 May 2015). "Quasar Quartet Embedded in Giant Nebula Reveals Rare Massive Structure in Distant Universe". Science 348 (6236): 779–783. doi:10.1126/science.aaa5397. PMID 25977547. Bibcode: 2015Sci...348..779H.

- ↑ Robert Naeye (10 January 2007). "The First Triple Quasar". Sky & Telescope. http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/5141272.html.

- ↑ Alan MacRobert (7 July 2006). "Binary Quasar Is No Illusion". Sky & Telescope. http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/3305801.html.

- ↑ SpaceDaily, "Extremely rare triple quasar found", 14 March 2013 (accessed 14 March 2013)

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Webster, A (1982). "The clustering of quasars from an objective-prism survey". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 199 (3): 683–705. doi:10.1093/mnras/199.3.683. Bibcode: 1982MNRAS.199..683W.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Clowes, Roger (2001). "Large Quasar Groups - A Short Review". The new era of wide field astronomy : proceedings of a conference held at the Centre for Astrophysics, University of Central Lancashire, Preston, United Kingdom, 21-24 August 2000. 232. Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 108. ISBN 1-58381-065-X. Bibcode: 2001ASPC..232..108C.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Clowes, Roger G.; Harris, Kathryn A.; Raghunathan, Srinivasan; Campusano, Luis E.; Soechting, Ilona K.; Graham, Matthew J. (2013). "A structure in the early universe at z ~ 1.3 that exceeds the homogeneity scale of the R-W concordance cosmology". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 429 (4): 2910–2916. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts497. Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.429.2910C.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 ScienceDaily, "Biggest Structure in Universe: Large Quasar Group Is 4 Billion Light Years Across", Royal Astronomical Society, 11 January 2013 (accessed 13 January 2013)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Unwin, Stephen C. (1987). "Superluminal motion in the quasar 3C279". Superluminal radio sources; Proceedings of the Workshop, Pasadena, Calif., 28–30 October 1986. Cambridge University Press. 34–39. Bibcode: 1987slrs.work...34U.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Preuss, E. (2002). "The Beginnings of VLBI at the 100-m Radio Telescope". in E. Ros. 6th European VLBI Network Symposium on New Developments in VLBI Science and Technology, held in Bonn, 25–28 June 25 2002. Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie. 1. Bibcode: 2002evn..conf....1P.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 Collin, Suzy (2006). "Quasars and Galactic Nuclei, a Half-Century Agitated Story". AIP Conference Proceedings 861: 587–595. doi:10.1063/1.2399629. Bibcode: 2006AIPC..861..587C.

- ↑ New Scientist, Quasar jets and cosmic engines: Some galaxies spew out vast amounts of material into space at velocities close to that of light. Astronomers still don't know why, 16 March 1991

- ↑ The superluminal radio source in the gamma-ray blazar 3C 279

- ↑ Porcas, R. W (1981). "Superluminal quasar 3C179 with double radio lobes". Nature 294 (5836): 47–49. doi:10.1038/294047a0. Bibcode: 1981Natur.294...47P.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Daily Intelligencer, The May 29, 1981;

- ↑ Walter Sullivan (27 December 1983). "If Nothing Is Faster than Light, What's Going On?". The New York Times: p. C1. https://www.nytimes.com/1983/12/27/science/if-nothing-is-faster-than-light-what-s-going-on.html?sec=health&pagewanted=1.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 The Structure of the Physical Universe, Volume III - The Universe of Motion, CHAPTER 23 - Quasar Redshifts , by Dewey Bernard Larson, Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 79-88078, ISBN 0-913138-11-8, Copyright 1959, 1971, 1984

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Quasars and Pulsars, Dewey Bernard Larson, (c) 1971; CHAPTER VIII - Quasars: The General Picture ; LOC 75-158894

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "The Quasi-Quasars". Time (magazine). 18 June 1965. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,898892,00.html.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : BSO 1, QSO B1246+377 -- Quasar

- ↑ Xaq Rzetelny (8 January 2015). "Supermassive black hole binary discovered". https://arstechnica.com/science/2015/01/supermassive-black-hole-binary-discovered/.

- ↑ Matthew J. Graham; S. George Djorgovski; Daniel Stern; Eilat Glikman; Andrew J. Drake; Ashish A. Mahabal; Ciro Donalek; Steve Larson et al. (25 July 2014). "A possible close supermassive black-hole binary in a quasar with optical periodicity". Nature 518 (7537): 74–76. 7 January 2015. doi:10.1038/nature14143. PMID 25561176. Bibcode: 2015Natur.518...74G.

- ↑ "X Rays from a Quasar". Time (magazine). 14 July 1967. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,899648,00.html.

- ↑ Discovery News, "Primordial 'Dust Free' Monsters Lurk at the Edge of the Universe", Ian O'Neill, 18 March 2010 (accessed 6 April 2010)

- ↑ DNA India, "Astronomers discover most primitive supermassive black holes known", ANI, 19 March 2010 (accessed 6 April 2010)

- ↑ "Most primitive supermassive black holes known 'discovered'". The Times of India. Press Trust of India. 19 March 2010. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/science/Most-primitive-supermassive-black-holes-known-discovered/articleshow/5701420.cms.

- ↑ Jiang, Linhua; Fan, Xiaohui; Brandt, W. N; Carilli, Chris L; Egami, Eiichi; Hines, Dean C; Kurk, Jaron D; Richards, Gordon T et al. (2010). "Dust-free quasars in the early Universe". Nature 464 (7287): 380–383. doi:10.1038/nature08877. PMID 20237563. Bibcode: 2010Natur.464..380J.

- ↑ Scientific Computing, "Fast-growing Primitive Black Holes found in Distant Quasars " (accessed 4 April 2010)

- ↑ SIMBAD, "QSO J0303-0019" (accessed 4 April 2010)

- ↑ SIMBAD, "QSO J0005-0006" (accessed 4 April 2010)

- ↑ "APOD: 2023 November 10 - UHZ1: Distant Galaxy and Black Hole". https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap231110.html.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Radio astronomers detect 'baby quasar' near the edge of the visible Universe, 13:50 EST, 6 June 2008

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : QSO J1427+3312, QSO J1427+3312 -- Quasar

- ↑ "Double black hole is powering quasar, astronomers find". 31 August 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/08/31/us/double-black-hole-nasa-hubble-feat/.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 Interview; "Maaarten Schmidt". http://oralhistories.library.caltech.edu/118/01/Schmidt96_OHO.pdf. (556 KB); 11 April and 2 & 15 May 1996

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 Shields, Gregory A. (June 1999). "A Brief History of Active Galactic Nuclei". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 111 (760): 661–678. doi:10.1086/316378. Bibcode: 1999PASP..111..661S.; Shields, G.. "A Brief History of AGN". http://nedwww.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/Sept04/Shields/Shields3.html.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Illingworth, Garth (1999). "Galaxies at High Redshift". Astrophysics and Space Science 269/270: 165–181. doi:10.1023/A:1017052809781. Bibcode: 1999Ap&SS.269..165I.; Illingworth, G.. "8. Z > 5 Galaxies". http://nedwww.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/Illingworth/Ill8.html.

- ↑ Schneider, Donald P. (August 2005). "The Sloan Digital Sky Survey Quasar Catalog. III. Third Data Release". The Astronomical Journal 130 (2): 367–380. doi:10.1086/431156. Bibcode: 2005AJ....130..367S.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Maria Temming (January 18, 2021), "The most ancient supermassive black hole is bafflingly big", Science News, https://www.sciencenews.org/article/most-ancient-supermassive-black-hole-quasar-bafflingly-big

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Scientific American, "Brilliant, but Distant: Most Far-Flung Known Quasar Offers Glimpse into Early Universe", John Matson, 29 June 2011

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Discovery.com Black Hole Is Most Distant Ever Found 7 June 2007

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 Willott, C. J. (2007). "Four Quasars above Redshift 6 Discovered by the Canada-France High-z Quasar Survey". The Astronomical Journal 134 (6): 2435–2450. doi:10.1086/522962. Bibcode: 2007AJ....134.2435W.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 CFHQS UOttawa, Canada-France High-z Quasar Survey

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 CFH UHawaii, Astronomers find most distant black hole

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bertoldi, F (2003). "High-excitation CO in a quasar host galaxy at z = 6.42". Astronomy & Astrophysics 409 (3): L47–L50. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20031345. Bibcode: 2003A&A...409L..47B.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Beelen, A. (2006). "350 Micron Dust Emission from High Redshift Quasars". The Astrophysical Journal 642 (2): 694–701. doi:10.1086/500636. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...642..694B.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Dokuchaev, V. I; Eroshenko, Yu. N; Rubin, S. G (2007). "Origin of supermassive black holes". arXiv:0709.0070 [astro-ph].

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 White, Richard L.; Becker, Robert H.; Fan, Xiaohui; Strauss, Michael A. (July 2003). "Probing the Ionization State of the Universe at z > 6". The Astronomical Journal 126 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1086/375547. Bibcode: 2003AJ....126....1W.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 65.6 65.7 Wang, Ran (2007). "Millimeter and Radio Observations of z~6 Quasars". The Astronomical Journal 134 (2): 617–627. doi:10.1086/518867. Bibcode: 2007AJ....134..617W.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Pentericci, L (2002). "VLT observations of the z = 6.28 quasar SDSS 1030+0524". The Astronomical Journal 123 (5): 2151. doi:10.1086/340077. Bibcode: 2002AJ....123.2151P.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Haiman, Zoltán; Cen, Renyue (2002). "A Constraint on the Gravitational Lensing Magnification and Age of the Redshift z = 6.28 Quasar SDSS 1030+0524". The Astrophysical Journal 578 (2): 702–7. doi:10.1086/342610. Bibcode: 2002ApJ...578..702H.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Farrah, D; Priddey, R; Wilman, R; Haehnelt, M; McMahon, R (2004). "The X-Ray Spectrum of the z = 6.30 QSO SDSS J1030+0524". The Astrophysical Journal 611 (1): L13. doi:10.1086/423669. Bibcode: 2004ApJ...611L..13F.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Fan, Xiaohui (December 2001). "A Survey of z > 5.8 Quasars in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Discovery of Three New Quasars and the Spatial Density of Luminous Quasars at z ~ 6". The Astronomical Journal 122 (6): 2833–2849. doi:10.1086/324111. Bibcode: 2001AJ....122.2833F.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 "Discovery Announced of Two Most Distant Objects". PennState Eberly College of Science. 5 June 2001. http://www.science.psu.edu/alert/Schneider6-2001.htm.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 SDSS, Early results from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey: From under our nose to the edge of the universe, June 2001

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : QSO B1425+3326 , QSO J1427+3312 -- Quasar

- ↑ Bañados, Eduardo (6 December 2017). "An 800-million-solar-mass black hole in a significantly neutral Universe at a redshift of 7.5". Nature 553 (7689): 473–476. doi:10.1038/nature25180. PMID 29211709. Bibcode: 2018Natur.553..473B.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 74.5 UW-Madison Astronomy, Confirmed High Redshift (z > 5.5) Galaxies - (Last Updated 10 February 2005)

- ↑ Iye, Masanori (2006). "A galaxy at a redshift z = 6.96". Nature 443 (7108): 186–8. doi:10.1038/nature05104. PMID 16971942. Bibcode: 2006Natur.443..186I.

- ↑ BBC News, Astronomers claim galaxy record, 11 July 2007, 17:10 GMT 18:10 UK

- ↑ New Scientist, New record for Universe's most distant object, 17:19 14 March 2002

- ↑ BBC News, Far away stars light early cosmos, 14 March 2002, 11:38 GMT

- ↑ BBC News, Most distant galaxy detected, 25 March 2003, 14:28 GMT

- ↑ Hu, E. M. (5 March 2002). "A Redshift z = 6.56 Galaxy behind the Cluster Abell 370". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 568 (2): L75–L79. doi:10.1086/340424. Bibcode: 2002ApJ...568L..75H.

- ↑ Kodaira, K (2003). "The Discovery of Two Lyman α Emitters Beyond Redshift 6 in the Subaru Deep Field". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan 55 (2): L17–L21. doi:10.1093/pasj/55.2.L17. Bibcode: 2003PASJ...55L..17K.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 "International Team of Astronomers Finds Most Distant Object". Science Journal (Eberly College of Science, PennState) 17 (1). Summer 2000. http://www.science.psu.edu/journal/Sum2000/DistObj.htm.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Hu, Esther M.; McMahon, Richard G.; Cowie, Lennox L. (3 August 1999). "An Extremely Luminous Galaxy at z = 5.74". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 522 (1): L9–L12. doi:10.1086/312205. Bibcode: 1999ApJ...522L...9H.

- ↑ PennState Eberly College of Science, X-rays from the Most Distant Quasar Captured with the XMM-Newton Satellite , Dec 2000

- ↑ SPACE.com, Most Distant Object in Universe Comes Closer, 1 December 2000

- ↑ NOAO Newsletter - NOAO Highlights - March 2000 - Number 61, The Most Distant Quasar Known

- ↑ Stern, Daniel (20 March 2002). "Chandra Detection of a Type II Quasar at z = 3.288". The Astrophysical Journal 568 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1086/338886. Bibcode: 2002ApJ...568...71S.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Stern, Daniel; Spinrad, Hyron; Eisenhardt, Peter; Bunker, Andrew J.; Dawson, Steve; Stanford, S. A.; Elston, Richard (20 April 2000). "Discovery of a Color-selected Quasar at z = 5.50". The Astrophysical Journal 533 (2): L75–L78. doi:10.1086/312614. PMID 10770694. Bibcode: 2000ApJ...533L..75S.

- ↑ SDSS 98-3 Scientists of Sloan Digital Sky Survey Discover Most Distant Quasar Dec 1998

- ↑ Fan, Xiaohui (January 2001). "High-Redshift Quasars Found in Sloan Digital Sky Survey Commissioning Data. IV. Luminosity Function from the Fall Equatorial Stripe Sample". The Astronomical Journal 121 (1): 54–65. doi:10.1086/318033. Bibcode: 2001AJ....121...54F.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : SDSSp J033829.31+002156.3, QSO J0338+0021 -- Quasar

- ↑ Henry Fountain (15 December 1998). "Observatory: Finding Distant Quasars". The New York Times: p. F5. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/15/science/observatory.html.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford (20 October 1988). "Peering Back in Time, Astronomers Glimpse Galaxies Aborning". The New York Times: p. F1. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/20/science/peering-back-in-time-astronomers-glimpse-galaxies-aborning.html?pagewanted=3.

- ↑ Smith, J. D (1994). "Multicolor detection of high-redshift quasars, 2: Five objects with Z greater than or approximately equal to 4". The Astronomical Journal 108: 1147. doi:10.1086/117143. Bibcode: 1994AJ....108.1147S. https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20170213-133303949.

- ↑ New Scientist, issue 1842, 10 October 1992, page 17, Science: Infant galaxy's light show

- ↑ FermiLab Scientists of Sloan Digital Sky Survey Discover Most Distant Quasar 8 December 1998

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Hook, I. M; McMahon, R. G (1998). "Discovery of radio-loud quasars with z = 4.72 and z = 4.010". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 294 (1): L7–L12. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.01368.x. Bibcode: 1998MNRAS.294L...7H.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 Turner, Edwin L (1991). "Quasars and galaxy formation. I - the Z greater than 4 objects". The Astronomical Journal 101: 5. doi:10.1086/115663. Bibcode: 1991AJ....101....5T.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : PC 1158+4635, QSO B1158+4635 -- Quasar

- ↑ Cowie, Lennox L (1991). "Young Galaxies". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 647 (1 Texas/ESO-Cer): 31–41. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb32157.x. Bibcode: 1991NYASA.647...31C.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 The New York Times, Peering to Edge of Time, Scientists Are Astonished, 20 November 1989

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 Warren, S. J; Hewett, P. C; Osmer, P. S; Irwin, M. J (1987). "Quasars of redshift z = 4.43 and z = 4.07 in the South Galactic Pole field". Nature 330 (6147): 453. doi:10.1038/330453a0. Bibcode: 1987Natur.330..453W.

- ↑ Levshakov, S. A (1989). "Absorption spectra of quasars". Astrophysics 29 (2): 657–671. doi:10.1007/BF01005972. Bibcode: 1988Ap.....29..657L.

- ↑ The New York Times, Objects Detected in Universe May Be the Most Distant Ever Sighted, 14 January 1988

- ↑ John Noble Wilford (10 May 1988). "Astronomers Peer Deeper Into Cosmo". The New York Times: p. C1. https://www.nytimes.com/1988/05/10/science/astronomers-peer-deeper-into-cosmos.html?pagewanted=all.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : Q0000-26, QSO B0000-26 -- Quasar

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 Schmidt, Maarten; Schneider, Donald P; Gunn, James E (1987). "PC 0910 + 5625 - an optically selected quasar with a redshift of 4.04". The Astrophysical Journal 321: L7. doi:10.1086/184996. Bibcode: 1987ApJ...321L...7S.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : PC 0910+5625, QSO B0910+5625 -- Quasar

- ↑ Warren, S. J.; Hewett, P. C.; Irwin, M. J.; McMahon, R. G.; Bridgeland, M. T.; Bunclark, P. S.; Kibblewhite, E. J. (8 January 1987). "First observation of a quasar with a redshift of 4". Nature 325 (6100): 131–133. doi:10.1038/325131a0. Bibcode: 1987Natur.325..131W.; First observation of a quasar with a redshift of 4

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : Q0046-293, QSO J0048-2903 -- Quasar

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : Q1208+1011, QSO B1208+1011 -- Quasar

- ↑ NewScientist, Quasar doubles help to fix the Hubble constant, 16 November 1991

- ↑ Orwell Astronomical Society (Ipswich) - OASI; Archived Astronomy News Items, 1972 - 1997

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : PKS 2000-330, QSO J2003-3251 -- Quasar

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 OSU Big Ear, History of the OSU Radio Observatory

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : OQ172, QSO B1442+101 -- Quasar

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 117.2 QUASARS - THREE YEARS LATER, 1974

- ↑ "The Edge of Night". Time (magazine). 23 April 1973. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,945213,00.html.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : OH471, QSO B0642+449 -- Quasar

- ↑ Warren, S J; Hewett, P C (1 August 1990). "The detection of high-redshift quasars". Reports on Progress in Physics 53 (8): 1095–1135. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/53/8/003. Bibcode: 1990RPPh...53.1095W.

- ↑ Bahcall, John N; Oke, J. B (1971). "Some Inferences from Spectrophotometry of Quasi-Stellar Sources". The Astrophysical Journal 163: 235. doi:10.1086/150762. Bibcode: 1971ApJ...163..235B.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 Lynds, R; Wills, D (1970). "The Unusually Large Redshift of 4C 05.34". Nature 226 (5245): 532. doi:10.1038/226532a0. PMID 16057373. Bibcode: 1970Natur.226..532L.

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : 5C 02.56, 7C 105517.75+495540.95 -- Quasar

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Burbidge, Geoffrey (1968). "The Distribution of Redshifts in Quasi-Stellar Objects, N-Systems and Some Radio and Compact Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal 154: L41. doi:10.1086/180265. Bibcode: 1968ApJ...154L..41B.

- ↑ Time Magazine, A Farther-Out Quasar, 7 April 1967

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : QSO B0237-2321, QSO B0237-2321 -- Quasar

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 127.2 127.3 Burbidge, Geoffrey (1967). "On the Wavelengths of the Absorption Lines in Quasi-Stellar Objects". The Astrophysical Journal 147: 851. doi:10.1086/149072. Bibcode: 1967ApJ...147..851B.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 Time Magazine, The Man on the Mountain, Friday, Mar. 11, 1966

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : Q1116+12, 4C 12.39 -- Quasar

- ↑ SIMBAD, Object query : Q0106+01, 4C 01.02 -- Quasar

- ↑ Malcolm S. Longair (2006). The Cosmic Century: A History of Astrophysics and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-47436-8. https://archive.org/details/cosmiccenturyhis0000long.

- ↑ Schmidt, Maarten (1965). "Large Redshifts of Five Quasi-Stellar Sources". The Astrophysical Journal 141: 1295. doi:10.1086/148217. Bibcode: 1965ApJ...141.1295S.

- ↑ Ivor Robinson, ed. "Introduction: The Discovery of Radio Galaxies and Quasars". Proceedings of the First Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics. The University of Chicago. http://www.astro.caltech.edu/~george/ay21/qso.txt.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 Schmidt, Maarten; Matthews, Thomas A (1964). "Redshift of the Quasi-Stellar Radio Sources 3c 47 and 3c 147". The Astrophysical Journal 139: 781. doi:10.1086/147815. Bibcode: 1964ApJ...139..781S.

- ↑ Schmidt, Maarten; Matthews, Thomas A. (1965). "Redshifts of the Quasi-Stellar Radio Sources 3c 47 and 3c 147". in Ivor Robinson. Quasi-Stellar Sources and Gravitational Collapse, Proceedings of the 1st Texas Symposium on Relativistic Astrophysics. University of Chicago Press. 269. Bibcode: 1965qssg.conf..269S.

- ↑ Schneider, Donald P; Van Gorkom, J. H; Schmidt, Maarten; Gunn, James E (1992). "Radio properties of optically selected high-redshift quasars. I - VLA observations of 22 quasars at 6 CM". The Astronomical Journal 103: 1451. doi:10.1086/116159. Bibcode: 1992AJ....103.1451S.

- ↑ "Finding the Fastest Galaxy: 76,000 Miles per Second". Time. 10 April 1964. http://aolsvc.timeforkids.kol.aol.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,875737,00.html.

- ↑ Greenstein, Jesse L; Matthews, Thomas A (1963). "Red-Shift of the Unusual Radio Source: 3C 48". Nature 197 (4872): 1041. doi:10.1038/1971041a0. Bibcode: 1963Natur.197.1041G.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 "1961 May 12 meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society". The Observatory 81: 113–118. 1961. Bibcode: 1961Obs....81..113..

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 P., Varshni, Y. (March 1979). "No redshift in 3C 295". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 11: 458. Bibcode: 1979BAAS...11..458V.

- ↑ The Origin of Matter Part 4

- ↑ Wolf, Christian (2018). "Discovery of the Most Ultra-Luminous QSO Using GAIA, Sky Mapper, and WISE". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 35: e024. doi:10.1017/pasa.2018.22. Bibcode: 2018PASA...35...24W.

- ↑ Bachev, R; Strigachev, A; Semkov, E (2005). "Short-term optical variability of high-redshift QSO's". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 358 (3): 774–780. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08708.x. Bibcode: 2005MNRAS.358..774B.

- ↑ Kuhn, O; Bechtold, J; Cutri, R; Elvis, M; Rieke, M (1995). "The spectral energy distribution of the z = 3 quasar: HS 1946+7658". The Astrophysical Journal 438: 643. doi:10.1086/175107. Bibcode: 1995ApJ...438..643K.

- ↑ Pâris, Isabelle (2012). "The Sloan Digital Sky Survey quasar catalog: Ninth data release". Astronomy & Astrophysics 548: A66. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220142. Bibcode: 2012A&A...548A..66P.

- ↑ Stern, Jonathan; Hennawi, Joseph F; Pott, Jörg-Uwe (2015). "Spatially Resolving the Kinematics of the <100 μas Quasar Broad Line Region using Spectroastrometry". The Astrophysical Journal 804 (1): 57. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/804/1/57. Bibcode: 2015ApJ...804...57S.

- ↑ Eisenhardt, Peter R. M (2012). "The First Hyper-Luminous Infrared Galaxy Discovered by WISE". The Astrophysical Journal 755 (2): 173. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/755/2/173. Bibcode: 2012ApJ...755..173E.

- ↑ Wu, Xue-Bing (2015). "An ultra-luminous quasar with a twelve-billion-solar-mass black hole at redshift 6.30". Nature 518 (7540): 512–515. doi:10.1038/nature14241. PMID 25719667. Bibcode: 2015Natur.518..512W.

- ↑ Stepanian, J. A.; Green, R. F.; Foltz, C. B.; Chaffee, F.; Chavushyan, V. H.; Lipovetsky, V. A.; Erastova, L. K. (December 2001). "Spectroscopy and Photometry of Stellar Objects from the Second Byurakan Survey". The Astronomical Journal 122 (6): 3361–3382. doi:10.1086/324460. Bibcode: 2001AJ....122.3361S.

- ↑ Onken, Christopher A.; Lai, Samuel; Wolf, Christian; Lucy, Adrian B.; Hon, Wei Jeat; Tisserand, Patrick; Sokoloski, Jennifer L.; Luna, Gerardo J. M. et al. (2022-06-08). "Discovery of the most luminous quasar of the last 9 Gyr". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 39. doi:10.1017/pasa.2022.36.

- ↑ Schneider, Donald P (2010). "The Sloan Digital Sky Survey Quasar Catalog V. Seventh Data Release". The Astronomical Journal 139 (6): 2360–2373. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/6/2360. Bibcode: 2010AJ....139.2360S.

- ↑ Schneider, Donald P. (July 2007). "The Sloan Digital Sky Survey Quasar Catalog. IV. Fifth Data Release". The Astronomical Journal 134 (1): 102–117. doi:10.1086/518474. Bibcode: 2007AJ....134..102S.

- ↑ Wu, Xue-Bing (2010). "A very bright i=16.44 quasar in the 'redshift desert' discovered by LAMOST". Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics 10 (8): 737. doi:10.1088/1674-4527/10/8/003. Bibcode: 2010RAA....10..737W.

External links

- Interactive interface into the catalog of Quasars from the Sloane Digital Sky Survey

- Catalogue of Bright Quasars and BL Lacertae Objects

- Kitt Peak Quasar List (1975) VII/11

- Revised and Updated Catalog of Quasi-stellar Objects (1993) VII/158

|

KSF

KSF