Phobos (moon)

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 34 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 34 min

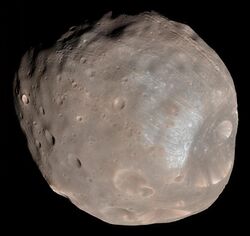

Enhanced image of Phobos from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter with the Stickney crater on the right, and the Limtoc crater within it near its right edge | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Asaph Hall |

| Discovery date | 18 August 1877 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Mars I |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfoʊbɒs/[1] or /ˈfoʊbəs/[2] |

| Named after | Φόβος |

| Adjectives | Phobian[3] /ˈfoʊbiən/[4] |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Epoch J2000 | |

| |{{{apsis}}}|apsis}} | 9234.42 km[5] |

| |{{{apsis}}}|apsis}} | 9517.58 km[5] |

| 9376 km[5] (2.76 Mars radii/1.472 Earth radii) | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0151[5] |

| Orbital period | 0.31891023 d (7 h 39 m 12 s) |

| Average Orbital speed | 2.138 km/s[5] |

| Inclination | 1.093° (to Mars's equator) 0.046° (to local Laplace plane) 26.04° (to the ecliptic) |

| Satellite of | Mars |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 25.90 × 22.60 × 18.32 km (± 0.08 × 0.08 × 0.06 km)[6] |

| Mean radius | 11.08±0.04 km[6] |

| Surface area | 1640±8 km2[6] |

| Volume | 5695±32 km3[6] |

| Mass | 1.0659×1016 kg[5] |

| Mean density | 1.861±0.011 g/cm3[6] |

| 0.0057 m/s2[5] (581.4 µ g) | |

| 11.39 m/s (41 km/h)[5] | |

| Rotation period | Synchronous |

| Equatorial rotation velocity | 11.0 km/h (6.8 mph) (at longest axis) |

| Axial tilt | 0° |

| Albedo | 0.071 ± 0.012 at 0.54 μm[7] |

| Physics | ≈ 233 K |

| Apparent magnitude | 11.8[8] |

Phobos (/ˈfoʊbɒs/; systematic designation: Mars I) is the innermost and larger of the two natural satellites of Mars,[9] the other being Deimos. The two moons were discovered in 1877 by American astronomer Asaph Hall. It is named after Phobos, the Greek god of fear and panic, who is the son of Ares (Mars) and twin brother of Deimos.

Phobos is a small, irregularly shaped object with a mean radius of 11 km (7 mi).[5] Phobos orbits 6,000 km (3,700 mi) from the Martian surface, closer to its primary body than any other known natural satellite to a planet. It orbits Mars much faster than Mars rotates and completes an orbit in just 7 hours and 39 minutes.[10] As a result, from the surface of Mars it appears to rise in the west, move across the sky in 4 hours and 15 minutes or less, and set in the east, twice each Martian day.

Phobos is one of the least reflective bodies in the Solar System, with an albedo of 0.071. Surface temperatures range from about −4 °C (25 °F) on the sunlit side to −112 °C (−170 °F) on the shadowed side.[11] The notable surface feature is the large impact crater, Stickney, which takes up a substantial proportion of the moon's surface. The surface is also home to many grooves, with there being numerous theories as to how these grooves were formed.

Images and models indicate that Phobos may be a rubble pile held together by a thin crust that is being torn apart by tidal interactions.[12] Phobos gets closer to Mars by about 2 cm per year, and it is predicted that within 30 to 50 million years it will either collide with the planet or break up into a planetary ring.[11]

Discovery

Phobos was discovered by astronomer Asaph Hall on 18 August 1877 at the United States Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C., at about 09:14 Greenwich Mean Time. (Contemporary sources, using the pre-1925 astronomical convention that began the day at noon,[13] give the time of discovery as 17 August at 16:06 Washington mean time, meaning 18 August 04:06 in the modern convention.)[14][15][16] Hall had discovered Deimos, Mars's other moon, a few days earlier on 12 August 1877 at about 07:48 UTC. The names, originally spelled Phobus and Deimus respectively, were suggested by Henry Madan (1838–1901), a science master at Eton College, based on Greek mythology, in which Phobos is a companion to the god, Ares.[17][18]

Physical characteristics

Phobos has dimensions of 27 km × 22 km × 18 km,[5] and retains too little mass to be rounded under its own gravity. Phobos does not have an atmosphere due to its low mass and low gravity.[19] It is one of the least reflective bodies in the Solar System, with an albedo of about 0.071.[20] Infrared spectra show that it has carbon-rich material found in carbonaceous chondrites, and its composition shows similarities to that of Mars' surface.[21] Phobos's density is too low to be solid rock, and it is known to have significant porosity.[22][23][24] These results led to the suggestion that Phobos might contain a substantial reservoir of ice. Spectral observations indicate that the surface regolith layer lacks hydration,[25][26] but ice below the regolith is not ruled out.[27][28]

Unlike Deimos, Phobos is heavily cratered,[30] with one of the craters near the equator having a central peak despite the moon's small size.[31] The most prominent of these is the crater Stickney, a large impact crater some 9 km (5.6 mi) in diameter, which takes up a substantial proportion of the moon's surface area. As with Mimas's crater Herschel, the impact that created Stickney must have nearly shattered Phobos.[32]

Many grooves and streaks also cover the oddly shaped surface. The grooves are typically less than 30 meters (98 ft) deep, 100 to 200 meters (330 to 660 ft) wide, and up to 20 kilometers (12 mi) in length, and were originally assumed to have been the result of the same impact that created Stickney. Analysis of results from the Mars Express spacecraft, however, revealed that the grooves are not in fact radial to Stickney, but are centered on the leading apex of Phobos in its orbit (which is not far from Stickney). Researchers suspect that they have been excavated by material ejected into space by impacts on the surface of Mars. The grooves thus formed as crater chains, and all of them fade away as the trailing apex of Phobos is approached. They have been grouped into 12 or more families of varying age, presumably representing at least 12 Martian impact events.[33] However, in November 2018, following further computational probability analysis, astronomers concluded that the many grooves on Phobos were caused by boulders, ejected from the asteroid impact that created Stickney crater. These boulders rolled in a predictable pattern on the surface of the moon.[34][35]

Faint dust rings produced by Phobos and Deimos have long been predicted but attempts to observe these rings have, to date, failed.[36] Recent images from Mars Global Surveyor indicate that Phobos is covered with a layer of fine-grained regolith at least 100 meters thick; it is hypothesized to have been created by impacts from other bodies, but it is not known how the material stuck to an object with almost no gravity.[37]

The unique Kaidun meteorite that fell on a Soviet military base in Yemen in 1980 has been hypothesized to be a piece of Phobos, but this couldn't be verified because little is known about the exact composition of Phobos.[38][39]

A person with a mass of 68 kilograms (150 pounds) would have the Earth-equivalent weight of about 40 grams (2 ounces) when standing on the surface of Phobos.

Shklovsky's "Hollow Phobos" hypothesis

In the late 1950s and 1960s, the unusual orbital characteristics of Phobos led to speculations that it might be hollow.[40] Around 1958, Russian astrophysicist Iosif Samuilovich Shklovsky, studying the secular acceleration of Phobos's orbital motion, suggested a "thin sheet metal" structure for Phobos, a suggestion which led to speculations that Phobos was of artificial origin.[41] Shklovsky based his analysis on estimates of the upper Martian atmosphere's density, and deduced that for the weak braking effect to be able to account for the secular acceleration, Phobos had to be very light—one calculation yielded a hollow iron sphere 16 kilometers (9.9 mi) across but less than 6 cm thick.[41][42] In a February 1960 letter to the journal Astronautics,[43] Fred Singer, then science advisor to U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, said of Shklovsky's theory:

If the satellite is indeed spiraling inward as deduced from astronomical observation, then there is little alternative to the hypothesis that it is hollow and therefore Martian made. The big 'if' lies in the astronomical observations; they may well be in error. Since they are based on several independent sets of measurements taken decades apart by different observers with different instruments, systematic errors may have influenced them.[43]

Subsequently, the systematic data errors that Singer predicted were found to exist, and the claim was called into doubt,[44] and accurate measurements of the orbit available by 1969 showed that the discrepancy did not exist.[45] Singer's critique was justified when earlier studies were discovered to have used an overestimated value of 5 cm/yr for the rate of altitude loss, which was later revised to 1.8 cm/yr.[46] The secular acceleration is now attributed to tidal effects, which create drag on the moon and therefore cause it spiral inward.[47]

The density of Phobos has now been directly measured by spacecraft to be 1.887 g/cm3.[48] Current observations are consistent with Phobos being a rubble pile.[48] In addition, images obtained by the Viking probes in the 1970s clearly showed a natural object, not an artificial one. Nevertheless, mapping by the Mars Express probe and subsequent volume calculations do suggest the presence of voids and indicate that it is not a solid chunk of rock but a porous body.[49] The porosity of Phobos was calculated to be 30% ± 5%, or a quarter to a third being empty.[50]

Named geological features

Geological features on Phobos are named after astronomers who studied Phobos and people and places from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels.[51]

Craters on Phobos

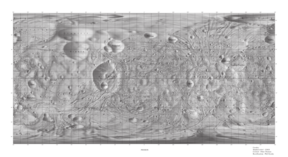

A number of craters have been named, and are listed in the following map and table.[52]

| Crater | Coordinates | Diameter (km) |

Approval Year |

Eponym | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clustril | [ ⚑ ] 60°N 91°W / 60°N 91°W | 3.4 | 2006 | Character in Lilliput who informed Flimnap that his wife had visited Gulliver privately in Jonathan Swift's novel Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| D'Arrest | [ ⚑ ] 39°S 179°W / 39°S 179°W | 2.1 | 1973 | Heinrich Louis d'Arrest; German/Danish astronomer (1822–1875) | WGPSN |

| Drunlo | [ ⚑ ] 36°30′N 92°00′W / 36.5°N 92°W | 4.2 | 2006 | Character in Lilliput who informed Flimnap that his wife had visited Gulliver privately in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Flimnap | [ ⚑ ] 60°N 10°E / 60°N 10°E | 1.5 | 2006 | Treasurer of Lilliput in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Grildrig | [ ⚑ ] 81°N 165°E / 81°N 165°E | 2.6 | 2006 | Name given to Gulliver by the farmer's daughter Glumdalclitch in the giants' country Brobdingnag in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Gulliver | [ ⚑ ] 62°N 163°W / 62°N 163°W | 5.5 | 2006 | Lemuel Gulliver; surgeon captain and voyager in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Hall | [ ⚑ ] 80°S 150°E / 80°S 150°E | 5.4 | 1973 | Asaph Hall; American astronomer discoverer of Phobos and Deimos (1829–1907) | WGPSN |

| Limtoc | [ ⚑ ] 11°S 54°W / 11°S 54°W | 2 | 2006 | General in Lilliput who prepared articles of impeachment against Gulliver in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Öpik | [ ⚑ ] 7°S 63°E / 7°S 63°E | 2 | 2011 | Ernst J. Öpik, Estonian astronomer (1893–1985) | WGPSN |

| Reldresal | [ ⚑ ] 41°N 39°W / 41°N 39°W | 2.9 | 2006 | Secretary for Private Affairs in Lilliput; Gulliver's friend in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Roche | [ ⚑ ] 53°N 177°E / 53°N 177°E | 2.3 | 1973 | Édouard Roche; French astronomer (1820–1883) | WGPSN |

| Sharpless | [ ⚑ ] 27°30′S 154°00′W / 27.5°S 154°W | 1.8 | 1973 | Bevan Sharpless; American astronomer (1904–1950) | WGPSN |

| Shklovsky | [ ⚑ ] 24°N 112°E / 24°N 112°E | 2 | 2011 | Iosif Shklovsky, Soviet astronomer (1916–1985) | WGPSN |

| Skyresh | [ ⚑ ] 52°30′N 40°00′E / 52.5°N 40°E | 1.5 | 2006 | Skyresh Bolgolam; High Admiral of the Lilliput council who opposed Gulliver's plea for freedom and accused him of being a traitor in Gulliver's Travels | WGPSN |

| Stickney | [ ⚑ ] 1°N 49°W / 1°N 49°W | 9 | 1973 | Angeline Stickney (1830–1892); wife of American astronomer Asaph Hall (above) | WGPSN |

| Todd | [ ⚑ ] 9°S 153°W / 9°S 153°W | 2.6 | 1973 | David Peck Todd; American astronomer (1855–1939) | WGPSN |

| Wendell | [ ⚑ ] 1°S 132°W / 1°S 132°W | 1.7 | 1973 | Oliver Wendell; American astronomer (1845–1912) | WGPSN |

Other named features

There is one named regio, Laputa Regio, and one named planitia, Lagado Planitia; both are named after places in Gulliver's Travels (the fictional Laputa, a flying island, and Lagado, imaginary capital of the fictional nation Balnibarbi).[53] The only named ridge on Phobos is Kepler Dorsum, named after the astronomer Johannes Kepler.[54]

Orbital characteristics

The orbital motion of Phobos has been intensively studied, making it "the best studied natural satellite in the Solar System" in terms of orbits completed.[55] Its close orbit around Mars produces some unusual effects. With an altitude of 5,989 km (3,721 mi), Phobos orbits Mars below the synchronous orbit radius, meaning that it moves around Mars faster than Mars itself rotates.[23] Therefore, from the point of view of an observer on the surface of Mars, it rises in the west, moves comparatively rapidly across the sky (in 4 h 15 min or less) and sets in the east, approximately twice each Martian day (every 11 h 6 min). Because it is close to the surface and in an equatorial orbit, it cannot be seen above the horizon from latitudes greater than 70.4°. Its orbit is so low that its angular diameter, as seen by an observer on Mars, varies visibly with its position in the sky. Seen at the horizon, Phobos is about 0.14° wide; at zenith it is 0.20°, one-third as wide as the full Moon as seen from Earth. By comparison, the Sun has an apparent size of about 0.35° in the Martian sky. Phobos's phases, inasmuch as they can be observed from Mars, take 0.3191 days (Phobos's synodic period) to run their course, a mere 13 seconds longer than Phobos's sidereal period.

Solar transits

File:Phobos transit in real color.webm An observer situated on the Martian surface, in a position to observe Phobos, would see regular transits of Phobos across the Sun. Several of these transits have been photographed by the Mars Rover Opportunity. During the transits, Phobos's shadow is cast on the surface of Mars; an event which has been photographed by several spacecraft. Phobos is not large enough to cover the Sun's disk, and so cannot cause a total eclipse.[56]

Predicted destruction

Tidal deceleration is gradually decreasing the orbital radius of Phobos by approximately two meters every 100 years,[12] and with decreasing orbital radius the likelihood of breakup due to tidal forces increases, estimated in approximately 30–50 million years,[12][55] with one study's estimate being about 43 million years.[57]

Phobos's grooves were long thought to be fractures caused by the impact that formed the Stickney crater. Other modelling suggested since the 1970s support the idea that the grooves are more like "stretch marks" that occur when Phobos gets deformed by tidal forces, but in 2015 when the tidal forces were calculated and used in a new model, the stresses were too weak to fracture a solid moon of that size, unless Phobos is a rubble pile surrounded by a layer of powdery regolith about 100 m (330 ft) thick. Stress fractures calculated for this model line up with the grooves on Phobos. The model is supported with the discovery that some of the grooves are younger than others, implying that the process that produces the grooves is ongoing.[12][58][inconsistent]

Given Phobos's irregular shape and assuming that it is a pile of rubble (specifically a Mohr–Coulomb body), it will eventually break up due to tidal forces when it reaches approximately 2.1 Mars radii.[59] When Phobos is broken up, it will form a planetary ring around Mars.[60] This predicted ring may last from 1 million to 100 million years. The fraction of the mass of Phobos that will form the ring depends on the unknown internal structure of Phobos. Loose, weakly bound material will form the ring. Components of Phobos with strong cohesion will escape tidal breakup and will enter the Martian atmosphere.[61]

Origin

The origin of the Martian moons has been disputed.[62] Phobos and Deimos both have much in common with carbonaceous C-type asteroids, with spectra, albedo, and density very similar to those of C- or D-type asteroids.[63] Based on their similarity, one hypothesis is that both moons may be captured main-belt asteroids.[64][65] Both moons have very circular orbits which lie almost exactly in Mars's equatorial plane, and hence a capture origin requires a mechanism for circularizing the initially highly eccentric orbit, and adjusting its inclination into the equatorial plane, most probably by a combination of atmospheric drag and tidal forces,[66] although it is not clear that sufficient time is available for this to occur for Deimos.[62] Capture also requires dissipation of energy. The current Martian atmosphere is too thin to capture a Phobos-sized object by atmospheric braking.[62] Geoffrey A. Landis has pointed out that the capture could have occurred if the original body was a binary asteroid that separated under tidal forces.[65][67]

Phobos could be a second-generation Solar System object that coalesced in orbit after Mars formed, rather than forming concurrently out of the same birth cloud as Mars.[68]

Another hypothesis is that Mars was once surrounded by many Phobos- and Deimos-sized bodies, perhaps ejected into orbit around it by a collision with a large planetesimal.[69] The high porosity of the interior of Phobos (based on the density of 1.88 g/cm3, voids are estimated to comprise 25 to 35 percent of Phobos's volume) is inconsistent with an asteroidal origin.[50] Observations of Phobos in the thermal infrared suggest a composition containing mainly phyllosilicates, which are well known from the surface of Mars. The spectra are distinct from those of all classes of chondrite meteorites, again pointing away from an asteroidal origin.[70] Both sets of findings support an origin of Phobos from material ejected by an impact on Mars that reaccreted in Martian orbit,[71] similar to the prevailing theory for the origin of Earth's moon.

Some areas of the surface are reddish in color, while others are bluish. The hypothesis is that gravity pull from Mars makes the reddish regolith move over the surface, exposing relatively fresh, unweathered and bluish material from the moon, while the regolith covering it over time has been weathered due to exposure of solar radiation. Because the blue rock differs from known Martian rock, it could contradict the theory that the moon is formed from leftover planetary material after the impact of a large object.[72]

Most recently,[when?] Amirhossein Bagheri (ETH Zurich), Amir Khan (ETH Zurich), Michael Efroimsky (US Naval Observatory) and their colleagues proposed a new hypothesis on the origin of the moons. By analyzing the seismic and orbital data from Mars InSight Mission and other missions, they proposed that the moons are born from disruption of a common parent body around 1 to 2.7 billion years ago. The common progenitor of Phobos and Deimos was most probably hit by another object and shattered to form both moons.[73]

Exploration

Launched missions

Phobos has been photographed in close-up by several spacecraft whose primary mission has been to photograph Mars. The first was Mariner 7 in 1969, followed by Mariner 9 in 1971, Viking 1 in 1977, Phobos 2 in 1989[74] Mars Global Surveyor in 1998 and 2003, Mars Express in 2004, 2008, 2010[75] and 2019, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2007 and 2008. On 25 August 2005, the Spirit rover, with an excess of energy due to wind blowing dust off of its solar panels, took several short-exposure photographs of the night sky from the surface of Mars, and was able to successfully photograph both Phobos and Deimos.[76]

The Soviet Union undertook the Phobos program with two probes, both launched successfully in July 1988. Phobos 1 was accidentally shut down by an erroneous command from ground control issued in September 1988 and lost while the craft was still en route. Phobos 2 arrived at the Mars system in January 1989 and, after transmitting a small amount of data and imagery but shortly before beginning its detailed examination of Phobos's surface, the probe abruptly ceased transmission due either to failure of the onboard computer or of the radio transmitter, already operating on the backup power. Other Mars missions collected more data, but no dedicated sample return mission has been performed.[citation needed]

The Russian Space Agency launched a sample return mission to Phobos in November 2011, called Fobos-Grunt. The return capsule also included a life science experiment of The Planetary Society, called Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, or LIFE.[77] A second contributor to this mission was the China National Space Administration, which supplied a surveying satellite called "Yinghuo-1", which would have been released in the orbit of Mars, and a soil-grinding and sieving system for the scientific payload of the Phobos lander.[78][79] However, after achieving Earth orbit, the Fobos–Grunt probe failed to initiate subsequent burns that would have sent it to Mars. Attempts to recover the probe were unsuccessful and it crashed back to Earth in January 2012.[80]

On 1 July 2020, the Mars orbiter of the Indian Space Research Organisation was able to capture photos of the body from 4,200 km away.[81]

Missions considered

In 1997 and 1998, the Aladdin mission was selected as a finalist in the NASA Discovery Program. The plan was to visit both Phobos and Deimos, and launch projectiles at the satellites. The probe would collect the ejecta as it performed a slow flyby (~1 km/s).[82] These samples would be returned to Earth for study three years later.[83][84] The Principal Investigator was Dr. Carle Pieters of Brown University. The total mission cost, including launch vehicle and operations was $247.7 million.[85] Ultimately, the mission chosen to fly was MESSENGER, a probe to Mercury.[86]

In 2007, the European aerospace subsidiary EADS Astrium was reported to have been developing a mission to Phobos as a technology demonstrator. Astrium was involved in developing a European Space Agency plan for a sample return mission to Mars, as part of the ESA's Aurora programme, and sending a mission to Phobos with its low gravity was seen as a good opportunity for testing and proving the technologies required for an eventual sample return mission to Mars. The mission was envisioned to start in 2016, was to last for three years. The company planned to use a "mothership", which would be propelled by an ion engine, releasing a lander to the surface of Phobos. The lander would perform some tests and experiments, gather samples in a capsule, then return to the mothership and head back to Earth where the samples would be jettisoned for recovery on the surface.[87]

Proposed missions

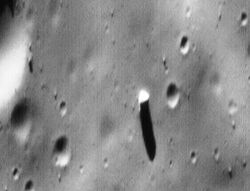

In 2007, the Canadian Space Agency funded a study by Optech and the Mars Institute for an uncrewed mission to Phobos known as Phobos Reconnaissance and International Mars Exploration (PRIME). A proposed landing site for the PRIME spacecraft is at the "Phobos monolith", a prominent object near Stickney crater.[88][89][90] The PRIME mission would be composed of an orbiter and lander, and each would carry 4 instruments designed to study various aspects of Phobos's geology.[91]

In 2008, NASA Glenn Research Center began studying a Phobos and Deimos sample return mission that would use solar electric propulsion. The study gave rise to the "Hall" mission concept, a New Frontiers-class mission under further study as of 2010.[92]

Another concept of a sample return mission from Phobos and Deimos is OSIRIS-REx II, which would use heritage technology from the first OSIRIS-REx mission.[93]

As of January 2013, a new Phobos Surveyor mission is currently under development by a collaboration of Stanford University, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[94] The mission is currently in the testing phases, and the team at Stanford plans to launch the mission between 2023 and 2033.[94]

In March 2014, a Discovery class mission was proposed to place an orbiter in Mars orbit by 2021 to study Phobos and Deimos through a series of close flybys. The mission is called Phobos And Deimos & Mars Environment (PADME).[95][96][97] Two other Phobos missions that were proposed for the Discovery 13 selection included a mission called Merlin, which would flyby Deimos but actually orbit and land on Phobos, and another one is Pandora which would orbit both Deimos and Phobos.[98]

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) unveiled on 9 June 2015 the Martian Moons Exploration (MMX), a sample return mission targeting Phobos.[99] MMX will land and collect samples from Phobos multiple times, along with conducting Deimos flyby observations and monitoring Mars's climate. By using a corer sampling mechanism, the spacecraft aims to retrieve a minimum 10 g amount of samples.[100] NASA, ESA, DLR, and CNES[101] are also participating in the project, and will provide scientific instruments.[102][103] The U.S. will contribute the Neutron and Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (NGRS), and France the Near IR Spectrometer (NIRS4/MacrOmega).[100][104] Although the mission has been selected for implementation[105][106] and is now beyond proposal stage, formal project approval by JAXA has been postponed following the Hitomi mishap.[107] Development and testing of key components, including the sampler, is currently ongoing.[108] As of 2017[update], MMX is scheduled to be launched in 2024, and will return to Earth five years later.[100]

Russia plans to repeat Fobos-Grunt mission in the late 2020s, and the European Space Agency is assessing a sample-return mission for 2024 called Phootprint.[109][110]

Human missions

Phobos has been proposed as an early target for a human mission to Mars. The teleoperation of robotic scouts on Mars by humans on Phobos could be conducted without significant time delay, and planetary protection concerns in early Mars exploration might be addressed by such an approach.[111]

Phobos has been proposed as an early target for a crewed mission to Mars because a landing on Phobos would be considerably less difficult and expensive than a landing on the surface of Mars itself. A lander bound for Mars would need to be capable of atmospheric entry and subsequent return to orbit without any support facilities, or would require the creation of support facilities in-situ. A lander instead bound for Phobos could be based on equipment designed for lunar and asteroid landings.[112] Furthermore, due to Phobos's very weak gravity, the delta-v required to land on Phobos and return is only 80% of that required for a trip to and from the surface of the Moon.[113]

It has been proposed that the sands of Phobos could serve as a valuable material for aerobraking during a Mars landing. A relatively small amount of chemical fuel brought from Earth could be used to lift a large amount of sand from the surface of Phobos to a transfer orbit. This sand could be released in front of a spacecraft during the descent maneuver causing a densification of the atmosphere just in front of the spacecraft.[114][115]

While human exploration of Phobos could serve as a catalyst for the human exploration of Mars, it could be scientifically valuable in its own right.[116]

Space elevator base

Phobos has been proposed as a future site for space elevator construction. This would involve a pair of space elevators: one extending 6,000 km from the Mars-facing side to the edge of Mars' atmosphere, the other extending 6,000 km from the other side and away from Mars. A spacecraft launching from Mars' surface to the lower space elevator would only need a delta-v of 0.52 km/s, as opposed to the over 3.6 km/s needed to launch to low Mars orbit. The spacecraft could be lifted up using electrical power and then released from the upper space elevator with a hyperbolic velocity of 2.6 km/sec, enough to reach Earth and a significant fraction of the velocity needed to reach the asteroid belt. The space elevators could also work in reverse to help spacecraft enter the Martian system. The great mass of Phobos means that any forces from space elevator operation would have minimal effect on its orbit. Additionally, materials from Phobos could be used for space industry.[117]

See also

- List of natural satellites

- List of missions to the moons of Mars

- Phobos monolith

- Transit of Phobos from Mars

References

- ↑ "Phobos". Phobos. Oxford University Press. http://www.lexico.com/definition/Phobos.

- ↑ "Moons of Mars – the Center for Planetary Science". http://planetary-science.org/mars-research/moons-of-mars/.

- ↑ Harry Shipman (2013) Humans in Space: 21st Century Frontiers, p. 317

- ↑ The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (1914)

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 "Mars: Moons: Phobos". NASA Solar System Exploration. 30 September 2003. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Mar_Phobos&Display=Facts.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Ernst, Carolyn M.Expression error: Unrecognized word "etal". (December 2023). "High-resolution shape models of Phobos and Deimos from stereophotoclinometry". Earth, Planets and Space 75 (1). doi:10.1186/s40623-023-01814-7. 103. Bibcode: 2023EP&S...75..103E.

- ↑ Clark, Beth Ellen (March 1998). "Near Photometry of C-Type Asteroid 253 Mathilde". 29th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. Lunar and Planetary Institute. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/LPSC98/pdf/1768.pdf. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ↑ "Mars' Moons". http://jtg.sjrdesign.net/advanced/mars_moons.html.

- ↑ "Mar's moon Phobos". http://mars.nasa.gov/allaboutmars/extreme/moons/phobos/.

- ↑ "ESA Science and Technology - Martian moons: Phobos". https://sci.esa.int/web/mars-express/-/31031-phobos.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "NASA – Phobos". Solarsystem.nasa.gov. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Mar_Phobos.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Zubritsky, Elizabeth (10 November 2015). "Mars' Moon Phobos is Slowly Falling Apart". NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/phobos-is-falling-apart.

- ↑ Campbell, W.W. (1918). "The Beginning of the Astronomical Day". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 30 (178): 358. doi:10.1086/122784. Bibcode: 1918PASP...30..358C.

- ↑ "Notes: The Satellites of Mars". The Observatory 1 (6): 181–185. 20 September 1877. Bibcode: 1877Obs.....1..181.. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/Obs../0001//0000181.000.html. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ↑ Hall, Asaph (17 October 1877). "Observations of the Satellites of Mars". Astronomische Nachrichten 91 (2161): 11/12–13/14. doi:10.1002/asna.18780910103. Bibcode: 1877AN.....91...11H. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/AN.../0091//0000013.000.html.

- ↑ Morley, Trevor A. (February 1989). "A Catalogue of Ground-Based Astrometric Observations of the Martian Satellites, 1877–1982". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 77 (2): 209–226. Bibcode: 1989A&AS...77..209M. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/A+AS./0077//0000220.000.html. (Table II, p. 220: first observation of Phobos on 18 August 1877.38498)

- ↑ Madan, Henry George (4 October 1877). "Letters to the Editor: The Satellites of Mars". Nature 16 (414): 475. doi:10.1038/016475b0. Bibcode: 1877Natur..16R.475M. https://books.google.com/books?id=fC4CAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA4-PA475.

- ↑ Hall, Asaph (14 March 1878). "Names of the Satellites of Mars". Astronomische Nachrichten 92 (2187): 47–48. doi:10.1002/asna.18780920304. Bibcode: 1878AN.....92...47H. http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/AN.../0092//0000031.000.html.

- ↑ "Solar System Exploration: Planets: Mars: Moons: Phobos: Overview". Solarsystem.nasa.gov. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Mar_Phobos.

- ↑ "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 13 July 2006. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par.

- ↑ Citron, R. I.; Genda, H.; & Ida, S. (2015), "Formation of Phobos and Deimos via a giant impact", Icarus, 252, p. 334-338, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.02.011

- ↑ "Porosity of Small Bodies and a Reassesment [sic] of Ida's Density". http://www.aas.org/publications/baas/v31n4/dps99/65.htm. "When the error bars are taken into account, only one of these, Phobos, has a porosity below 0.2..."

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Close Inspection for Phobos". http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=31031. "It is light, with a density less than twice that of water, and orbits just 5,989 kilometers (3,721 mi) above the Martian surface."

- ↑ Busch, Michael W.; Ostro, Steven J.; Benner, Lance A. M.; Giorgini, Jon D. et al. (2007). "Arecibo Radar Observations of Phobos and Deimos". Icarus 186 (2): 581–584. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.11.003. Bibcode: 2007Icar..186..581B.

- ↑ Murchie, Scott L.; Erard, Stephane; Langevin, Yves; Britt, Daniel T. et al. (1991). "Disk-resolved Spectral Reflectance Properties of Phobos from 0.3–3.2 microns: Preliminary Integrated Results from PhobosH 2". Abstracts of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 22: 943. Bibcode: 1991pggp.rept..249M.

- ↑ Rivkin, Andrew S.; Brown, Robert H.; Trilling, David E.; Bell III, James F. et al. (March 2002). "Near-Infrared Spectrophotometry of Phobos and Deimos". Icarus 156 (1): 64–75. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6767. Bibcode: 2002Icar..156...64R.

- ↑ Fanale, Fraser P.; Salvail, James R. (1989). "Loss of water from Phobos". Geophys. Res. Lett. 16 (4): 287–290. doi:10.1029/GL016i004p00287. Bibcode: 1989GeoRL..16..287F.

- ↑ Fanale, Fraser P.; Salvail, James R. (Dec 1990). "Evolution of the water regime of Phobos". Icarus 88 (2): 380–395. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(90)90089-R. Bibcode: 1990Icar...88..380F.

- ↑ USGS Staff. "Phobos Map – Shaded Relief". USGS. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/images/phobos-cylindrical-grid.pdf.

- ↑ "Phobos". BBC Online. 12 January 2004. http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/space/solarsystem/mars/phobos.shtml.

- ↑ "Viking looks at Phobos in detail". New Scientist (Reed Business Information) 72 (1023): 158. 21 October 1976. ISSN 0262-4079. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q6tkzO06q4oC&pg=PA158. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ "Stickney Crater-Phobos". http://www.solarviews.com/cap/mars/phobos2.htm. "One of the most striking features of Phobos, aside from its irregular shape, is its giant crater Stickney. Because Phobos is only 28 by 20 kilometers (17 by 12 mi), it must have been nearly shattered from the force of the impact that caused the giant crater. Grooves that extend across the surface from Stickney appear to be surface fractures caused by the impact."

- ↑ Murray, John B.; Murray, John B.; Iliffe, Jonathan C.; Muller, Jan-Peter A. L.; Neukum, Gerhard; Werner, Stephanie; Balme, Matt; HRSC Co-Investigator Team. "New Evidence on the Origin of Phobos' Parallel Grooves from HRSC Mars Express". 37th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, March 2006. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2006/pdf/2195.pdf.

- ↑ Gough, Evan (20 November 2018). "Strange Grooves on Phobos Were Caused by Boulders Rolling Around on its Surface". Universe Today. https://www.universetoday.com/140593/strange-grooves-on-phobos-were-caused-by-boulders-rolling-around-on-its-surface/.

- ↑ Ramsley, Kenneth R.; Head, James W. (2019). "Origin of Phobos grooves: Testing the Stickney Crater ejecta model". Planetary and Space Science 165: 137–147. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2018.11.004. Bibcode: 2019P&SS..165..137R.

- ↑ Showalter, Mark R.; Hamilton, Douglas P.; Nicholson, Philip D. (2006). "A Deep Search for Martian Dust Rings and Inner Moons Using the Hubble Space Telescope". Planetary and Space Science 54 (9–10): 844–854. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2006.05.009. Bibcode: 2006P&SS...54..844S. http://www.astro.umd.edu/~hamilton/research/reprints/ShoHamNic06.pdf.

- ↑ Britt, Robert Roy (13 March 2001). "Forgotten Moons: Phobos and Deimos Eat Mars' Dust". space.com. http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/forgotten_moons_010313-3.html.

- ↑ Ivanov, Andrei V. (March 2004). "Is the Kaidun Meteorite a Sample from Phobos?". Solar System Research 38 (2): 97–107. doi:10.1023/B:SOLS.0000022821.22821.84. Bibcode: 2004SoSyR..38...97I.

- ↑ Ivanov, Andrei; Zolensky, Michael (2003). "The Kaidun Meteorite: Where Did It Come From?". Lunar and Planetary Science 34. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2003/pdf/1236.pdf. "The currently available data on the lithologic composition of the Kaidun meteorite– primarily the composition of the main portion of the meteorite, corresponding to CR2 carbonaceous chondrites and the presence of clasts of deeply differentiated rock – provide weighty support for considering the meteorite’s parent body to be a carbonaceous chondrite satellite of a large differentiated planet. The only possible candidates in the modern Solar System are Phobos and Deimos, the moons of Mars.".

- ↑ "A Convenient Truth - One Universe at a Time". 12 July 2017. https://archive.briankoberlein.com/2017/07/12/a-convenient-truth/index.html.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Shklovsky, Iosif Samuilovich; The Universe, Life, and Mind, Academy of Sciences USSR, Moscow, 1962

- ↑ Öpik, Ernst Julius (September 1964). "Is Phobos Artificial?". Irish Astronomical Journal 6: 281–283. Bibcode: 1964IrAJ....6..281..

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Singer, S. Fred; Astronautics, February 1960

- ↑ Öpik, Ernst Julius (March 1963). "News and Comments: Phobos, Nature of Acceleration". Irish Astronomical Journal 6: 40. Bibcode: 1963IrAJ....6R..40..

- ↑ Singer, S. Fred (1967), "On the Origin of the Martian Satellites Phobos and Deimos", The Moon and the Planets: 317, Bibcode: 1967mopl.conf..317S

- ↑ Singer, S. Fred; "More on the Moons of Mars", Astronautics, February 1960. American Astronautical Society, page 16

- ↑ Efroimsky, Michael; Lainey, Valéry (29 December 2007). "Physics of bodily tides in terrestrial planets and the appropriate scales of dynamical evolution". Journal of Geophysical Research—Planets 112: p. E12003. doi:10.1029/2007JE002908.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Mars Express closes in on the origin of Mars' larger moon". DLR. 16 October 2008. http://www.dlr.de/mars/en/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-207/422_read-13776/.

- ↑ Clark, Stuart; "Cheap Flights to Phobos" in New Scientist magazine, 30 January 2010

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Andert, Thomas P.; Rosenblatt, Pascal; Pätzold, Martin; Häusler, Bernd et al. (7 May 2010). "Precise mass determination and the nature of Phobos". Geophysical Research Letters 37 (9): L09202. doi:10.1029/2009GL041829. Bibcode: 2010GeoRL..37.9202A.

- ↑ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature USGS Astrogeology Research Program, Categories

- ↑ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature USGS Astrogeology Research Program, Craters

- ↑ Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature USGS Astrogeology Research Program, Phobos

- ↑ "Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (Groupe de Travail Pour la Nomenclature du Systeme Planetaire)". Transactions of the International Astronomical Union 20 (2): 372. 1988. doi:10.1017/S0251107X0002767X.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Bills, Bruce G.; Neumann, Gregory A.; Smith, David E.; Zuber, Maria T. (2005). "Improved estimate of tidal dissipation within Mars from MOLA observations of the shadow of Phobos". Journal of Geophysical Research 110 (E07004): E07004. doi:10.1029/2004je002376. Bibcode: 2005JGRE..110.7004B.

- ↑ Mary Beth Griggs (April 21, 2022). "Check out NASA's latest footage of a solar eclipse on Mars". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/4/21/23035514/nasa-perseverance-rover-mars-eclipse-phobos.

- ↑ Efroimsky, Michael; Lainey, Valéry (2007). "Physics of bodily tides in terrestrial planets and the appropriate scales of dynamical evolution.". Journal of Geophysical Research 112 (E12): E12003. doi:10.1029/2007JE002908. Bibcode: 2007JGRE..11212003E.

- ↑ Hurford, Terry A.; Asphaug, Erik; Spitale, Joseph; Hemingway, Douglas; et al.; "Surface Evolution from Orbital Decay on Phobos", Division of Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society meeting #47, National Harbor, MD, November 2015

- ↑ Holsapple, Keith A. (December 2001). "Equilibrium Configurations of Solid Cohesionless Bodies". Icarus 154 (2): 432–448. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6683. Bibcode: 2001Icar..154..432H. http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/131a/1b59e2f721e98b95653327f691ef171a4e63.pdf.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (23 November 2015). "Gravity will rip Martian moon apart to form dust and rubble ring". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/nov/23/gravity-will-rip-mars-moon-apart-dust-rubble-ring.

- ↑ Black, Benjamin A.; and Mittal, Tushar; (2015), "The demise of Phobos and development of a Martian ring system", Nature Geosci, advance online publication, doi:10.1038/ngeo2583

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Burns, Joseph A.; "Contradictory Clues as to the Origin of the Martian Moons" in Mars, H. H. Kieffer et al., eds., University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ, 1992

- ↑ "Views of Phobos and Deimos". NASA. 27 November 2007. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/MRO/multimedia/20071127-caption.html.

- ↑ "Close Inspection for Phobos". http://sci.esa.int/science-e/www/object/index.cfm?fobjectid=31031. "One idea is that Phobos and Deimos, Mars's other moon, are captured asteroids."

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Landis, Geoffrey A.; "Origin of Martian Moons from Binary Asteroid Dissociation", American Association for the Advancement of Science Annual Meeting; Boston, MA, 2001, abstract

- ↑ Canup, Robin (2018-04-18). "Origin of Phobos and Deimos by the impact of a Vesta-to-Ceres sized body with Mars". Science Advances 4 (4): eaar6887. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar6887. PMID 29675470. Bibcode: 2018SciA....4.6887C.

- ↑ Pätzold, Martin; Witasse, Olivier (4 March 2010). "Phobos Flyby Success". ESA. https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Space_Science/Mars_Express/Phobos_flyby_success.

- ↑ Craddock, Robert A.; (1994); "The Origin of Phobos and Deimos", Abstracts of the 25th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, held in Houston, TX, 14–18 March 1994, p. 293

- ↑ Giuranna, Marco; Roush, Ted L.; Duxbury, Thomas; Hogan, Robert C.; Geminale, Anna; Formisano, Vittorio (2010). "Compositional Interpretation of PFS/MEx and TES/MGS Thermal Infrared Spectra of Phobos". http://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC2010/EPSC2010-211.pdf. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ↑ "Mars Moon Phobos Likely Forged by Catastrophic Blast". Space.com. 27 September 2010. https://www.space.com/9201-mars-moon-phobos-forged-catastrophic-blast.html.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (18 March 2019). "A Weird Powder Puzzle on the Martian Moon Phobos May Be Solved". Space.com. https://www.space.com/mars-moon-phobos-orbit-surface-powder.html.

- ↑ Bagheri, Amirhossein; Khan, Amir; Efroimsky, Michael; Kruglyakov, Mikhail; Giardini, Domenico (2021-02-22). "Dynamical evidence for Phobos and Deimos as remnants of a disrupted common progenitor" (in en). Nature Astronomy 5 (6): 539–543. doi:10.1038/s41550-021-01306-2. ISSN 2397-3366. Bibcode: 2021NatAs...5..539B. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-021-01306-2.

- ↑ Harvey, Brian (2007). Russian Planetary Exploration History, Development, Legacy and Prospects. Springer-Praxis. pp. 253–254. ISBN 9780387463438.

- ↑ "Closest Phobos flyby gathers data". BBC News (London). 4 March 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/8550362.stm.

- ↑ "Two Moons Passing in the Night". NASA. http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/press/spirit/20050909a.html.

- ↑ "Projects LIFE Experiment: Phobos". The Planetary Society. http://www.planetary.org/programs/projects/life/.

- ↑ "HK triumphs with out of this world invention". Hong Kong Trader. 1 May 2007. http://www.hktrader.net/200705/lead/lead-SpaceMission200705.htm.

- ↑ "PolyU-made space tool sets for Mars again". Hong Kong Polytechnic University. 2 April 2007. https://www.polyu.edu.hk/web/en/media/media_releases/index_id_815.html.

- ↑ "Russia's Failed Phobos-Grunt Space Probe Heads to Earth". BBC News. 14 January 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-16491457.

- ↑ "Phobos imaged by MOM on 1st July". Indian Space Research Organisation. 2020-07-05. https://www.isro.gov.in/pslv-c25-mars-orbiter-mission/phobos-imaged-mom-1st-july.

- ↑ Barnouin-Jha, Olivier S. (1999). "Aladdin: Sample return from the moons of Mars". 1999 IEEE Aerospace Conference. Proceedings (Cat. No.99TH8403). 1. pp. 403–412 vol.1. doi:10.1109/AERO.1999.794346. ISBN 978-0-7803-5425-8.

- ↑ Pieters, Carle. "Aladdin: Phobos -Deimos Sample Return". 28th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc97/pdf/1113.PDF.

- ↑ "Messenger and Aladdin Missions Selected as NASA Discovery Program Candidates". http://www.jhuapl.edu/newscenter/pressreleases/1998/managed.asp.

- ↑ "Five Discovery mission proposals selected for feasibility studies". http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/text/discovery_pr_19981112.txt.

- ↑ "NASA Selects Missions to Mercury and a Comet's Interior as Next Discovery Flights". http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/news/discovery_pr_19990707.html.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan; Martian Moon ’Could be Key Test’, BBC News (9 February 2007)

- ↑ Optech press release, "Canadian Mission Concept to Mysterious Mars moon Phobos to Feature Unique Rock-Dock Maneuver", 3 May 2007

- ↑ PRIME: Phobos Reconnaissance & International Mars Exploration , Mars Institute website, accessed 27 July 2009.

- ↑ Lee, Pascal; Richards, Robert; Hildebrand, Alan; and the PRIME Mission Team 2008, "The PRIME (Phobos Reconnaissance and International Mars Exploration) Mission and Mars sample Return", in 39th Lunar Planetary Science Conference, Houston, TX, March 2008, [#2268]

- ↑ Mullen, Leslie (30 April 2009). "New Missions Target Mars Moon Phobos". Astrobiology Magazine (Space.com). http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/090430-mars-phobos-missions.html.

- ↑ Lee, Pascal; Veverka, Joseph F.; Bellerose, Julie; Boucher, Marc; et al.; 2010; "Hall: A Phobos and Deimos Sample Return Mission", 44th Lunar Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, TX. 1–5 Mar 2010. [#1633] Bibcode: 2010LPI....41.1633L .

- ↑ Elifritz, Thomas Lee; (2012); OSIRIS-REx II to Mars. (PDF)

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Pandika, Melissa (28 December 2012). "Stanford researchers develop acrobatic space rovers to explore moons and asteroids". Stanford Report. Stanford News Service (Stanford, CA). http://news.stanford.edu/news/2012/december/rover-mars-phobos-122812.html.

- ↑ Lee, Pascal; Bicay, Michael; Colapre, Anthony; Elphic, Richard (17–21 March 2014). "Phobos And Deimos & Mars Environment (PADME): A LADEE-Derived Mission to Explore Mars's Moons and the Martian Orbital Environment". 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014). http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2014/pdf/2288.pdf.

- ↑ Reyes, Tim (1 October 2014). "Making the Case for a Mission to the Martian Moon Phobos". Universe Today. http://www.universetoday.com/114871/making-the-case-for-a-mission-to-the-martian-moon-phobos/.

- ↑ Lee, Pascal; Benna, Mehdi; Britt, Daniel T.; Colaprete, Anthony (16–20 March 2015). "PADME (Phobos And Deimos & Mars Environment): A Proposed NASA Discovery Mission to Investigate the Two Moons of Mars". 46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015). http://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2015/pdf/2856.pdf.

- ↑ MERLIN: The Creative Choices Behind a Proposal to Explore the Martian Moons (Merlin and PADME info also)

- ↑ "JAXA plans probe to bring back samples from moons of Mars". The Japan Times Online. 10 June 2015. http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/06/10/national/science-health/jaxa-plans-probe-bring-back-samples-martian-moons/.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 Fujimoto, Masaki (11 January 2017). "JAXA's exploration of the two moons of Mars, with sample return from Phobos". Lunar and Planetary Institute. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/sbag/meetings/jan2017/presentations/Fujimoto.pdf.

- ↑ "Coopération spatiale entre la France et le Japon Rencontre à Paris entre le CNES et la JAXA-ISAS" (PDF) (Press release) (in français). CNES. 10 February 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- ↑ "ISASニュース 2017.1 No.430" (in ja). Institute of Space and Astronautical Science. 22 January 2017. http://www.isas.jaxa.jp/outreach/isas_news/files/ISASnews430.pdf.

- ↑ Green, James (7 June 2016). "Planetary Science Division Status Report". Lunar and Planetary Institute. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/pss/jun2016/presentations/Green.pdf#page=22.

- ↑ "A Study of Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging of Martian Moons by NIRS4/MACROMEGA onboard MMX Spacecraft". Lunar and Planetary Institute. 23 March 2017. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2017/pdf/2813.pdf.

- ↑ "Observation plan for Martian meteors by Mars-orbiting MMX spacecraft" (PowerPoint). 10 June 2016. https://www.cosmos.esa.int/documents/653713/1049906/08+Yamamoto20160610.ppt/1d540dc8-5053-4732-8af1-db6be0c5ae4e.

- ↑ "A giant impact: Solving the mystery of how Mars' moons formed". ScienceDaily. 4 July 2016. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/07/160704144236.htm.

- ↑ Tsuneta, Saku (10 June 2016). "JAXA Space Science Program and International Cooperation". https://www.slideshare.net/ISAS_Director_Tsuneta/jaxa-space-science-program-and-international-collaboration-69619024.

- ↑ "ISASニュース 2016.7 No.424" (in ja). Institute of Space and Astronautical Science. 22 July 2016. http://www.isas.jaxa.jp/outreach/isas_news/files/ISASnews424.pdf#page=6.

- ↑ Barraclough, Simon; Ratcliffe, Andrew; Buchwald, Robert; Scheer, Heloise; Chapuy, Marc; Garland, Martin (16 June 2014). "Phootprint: A European Phobos Sample Return Mission". 11th International Planetary Probe Workshop. Airbus Defense and Space. http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/docs/03_Phootprint_A%20European%20Phobos%20Sample%20Return%20Mission_Ratcliffe.pdf. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ↑ Koschny, Detlef; Svedhem, Håkan; Rebuffat, Denis (2 August 2014). "Phootprint – A Phobos sample return mission study". ESA 40: B0.4–9–14. Bibcode: 2014cosp...40E1592K.

- ↑ Landis, Geoffrey A.; "Footsteps to Mars: an Incremental Approach to Mars Exploration", in Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, vol. 48, pp. 367–342 (1995); presented at Case for Mars V, Boulder CO, 26–29 May 1993; appears in From Imagination to Reality: Mars Exploration Studies, R. Zubrin, ed., AAS Science and Technology Series Volume 91, pp. 339–350 (1997). (text available asFootsteps to Mars)

- ↑ Lee, Pascal; Braham, Stephen; Mungas, Greg; Silver, Matt; Thomas, Peter C.; and West, Michael D. (2005), "Phobos: A Critical Link Between Moon and Mars Exploration", Report of the Space Resources Rountable VII: LEAG Conference on Lunar Exploration, League City, TX 25–28 Oct 2005. LPI Contrib. 1318, p. 72. Bibcode: 2005LPICo1287...56L

- ↑ Oberg, Jamie (20 May 2009). "Russia's Dark Horse Plan to Get to Mars". Discover. https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/russias-dark-horse-plan-to-get-to-mars. "The total delta-v required for a mission to land on Phobos and come back is startlingly low—only about 80 percent that of a round trip to the surface of Earth’s moon. (That is in part because of Phobos’s feeble gravity; a well-aimed pitch could launch a softball off its surface.)"

- ↑ Arias, Francisco. J (2017). On the Use of the Sands of Phobos and Deimos as a Braking Technique for Landing Large Payloads on Mars. doi:10.2514/6.2017-4876. ISBN 978-1-62410-511-1.

- ↑ Arias, Francisco. J; De Las Heras, Salvador. A (2019). "Sandbraking. A technique for landing large payloads on Mars using the sands of Phobos". Aerospace Science and Technology 85: 409–415. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2018.11.041. ISSN 1270-9638.

- ↑ Lee, Pascal (5–7 November 2007). "Phobos-Deimos ASAP: A Case for the Human Exploration of the Moons of Mars". First Int’l Conf. Explor. Phobos & Deimos. NASA Research Park, Moffett Field, CA: USRA. p. 25 [#7044]. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/phobosdeimos2007/pdf/7044.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Weinstein, Leonard M. (January 2003). "Space Colonization Using Space-Elevators from Phobos" (in en). AIP Conference Proceedings 654: 1227–1235. doi:10.1063/1.1541423. Bibcode: 2003AIPC..654.1227W. https://space.nss.org/wp-content/uploads/2003-Space-Colonization-Using-Space-Elevators-From-Phobos.pdf. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Phobos Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- HiRISE Phobos

- USGS Phobos nomenclature

- Asaph Hall and the Moons of Mars

- Flight around Phobos (movie)

- Animation of Phobos

- Scale of Phobos [1] [2]

- Mars Express view of Phobos

- Phobos cartography (MIIGAiK Extraterrestrial Laboratory)

|

KSF

KSF